II.2 Geometry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hydraulic Cylinder Replacement for Cylinders with 3/8” Hydraulic Hose Instructions

HYDRAULIC CYLINDER REPLACEMENT FOR CYLINDERS WITH 3/8” HYDRAULIC HOSE INSTRUCTIONS INSTALLATION TOOLS: INCLUDED HARDWARE: • Knife or Scizzors A. (1) Hydraulic Cylinder • 5/8” Wrench B. (1) Zip-Tie • 1/2” Wrench • 1/2” Socket & Ratchet IMPORTANT: Pressure MUST be relieved from hydraulic system before proceeding. PRESSURE RELIEF STEP 1: Lower the Power-Pole Anchor® down so the Everflex™ spike is touching the ground. WARNING: Do not touch spike with bare hands. STEP 2: Manually push the anchor into closed position, relieving pressure. Manually lower anchor back to the ground. REMOVAL STEP 1: Remove the Cylinder Bottom from the Upper U-Channel using a 1/2” socket & wrench. FIG 1 or 2 NOTE: For Blade models, push bottom of cylinder up into U-Channel and slide it forward past the Ram Spacers to remove it. Upper U-Channel Upper U-Channel Cylinder Bottom 1/2” Tools 1/2” Tools Ram 1/2” Tools Spacers Cylinder Bottom If Ram-Spacers fall out Older models have (1) long & (1) during removal, push short Ram Spacer. Ram Spacers 1/2” Tools bushings in to hold MUST be installed on the same side Figure 1 Figure 2 them in place. they were removed. Blade Models Pro/Spn Models Need help? Contact our Customer Service Team at 1 + 813.689.9932 Option 2 HYDRAULIC CYLINDER REPLACEMENT FOR CYLINDERS WITH 3/8” HYDRAULIC HOSE INSTRUCTIONS STEP 2: Remove the Cylinder Top from the Lower U-Channel using a 1/2” socket & wrench. FIG 3 or 4 Lower U-Channel Lower U-Channel 1/2” Tools 1/2” Tools Cylinder Top Cylinder Top Figure 3 Figure 4 Blade Models Pro/SPN Models STEP 3: Disconnect the UP Hose from the Hydraulic Cylinder Fitting by holding the 1/2” Wrench 5/8” Wrench Cylinder Fitting Base with a 1/2” wrench and turning the Hydraulic Hose Fitting Cylinder Fitting counter-clockwise with a 5/8” wrench. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

Volumes of Prisms and Cylinders 625

11-4 11-4 Volumes of Prisms and 11-4 Cylinders 1. Plan Objectives What You’ll Learn Check Skills You’ll Need GO for Help Lessons 1-9 and 10-1 1 To find the volume of a prism 2 To find the volume of • To find the volume of a Find the area of each figure. For answers that are not whole numbers, round to prism a cylinder the nearest tenth. • To find the volume of a 2 Examples cylinder 1. a square with side length 7 cm 49 cm 1 Finding Volume of a 2. a circle with diameter 15 in. 176.7 in.2 . And Why Rectangular Prism 3. a circle with radius 10 mm 314.2 mm2 2 Finding Volume of a To estimate the volume of a 4. a rectangle with length 3 ft and width 1 ft 3 ft2 Triangular Prism backpack, as in Example 4 2 3 Finding Volume of a Cylinder 5. a rectangle with base 14 in. and height 11 in. 154 in. 4 Finding Volume of a 6. a triangle with base 11 cm and height 5 cm 27.5 cm2 Composite Figure 7. an equilateral triangle that is 8 in. on each side 27.7 in.2 New Vocabulary • volume • composite space figure Math Background Integral calculus considers the area under a curve, which leads to computation of volumes of 1 Finding Volume of a Prism solids of revolution. Cavalieri’s Principle is a forerunner of ideas formalized by Newton and Leibniz in calculus. Hands-On Activity: Finding Volume Explore the volume of a prism with unit cubes. -

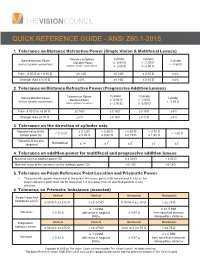

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

A Three-Dimensional Laguerre Geometry and Its Visualization

A Three-Dimensional Laguerre Geometry and Its Visualization Hans Havlicek and Klaus List, Institut fur¨ Geometrie, TU Wien 3 We describe and visualize the chains of the 3-dimensional chain geometry over the ring R("), " = 0. MSC 2000: 51C05, 53A20. Keywords: chain geometry, Laguerre geometry, affine space, twisted cubic. 1 Introduction The aim of the present paper is to discuss in some detail the Laguerre geometry (cf. [1], [6]) which arises from the 3-dimensional real algebra L := R("), where "3 = 0. This algebra generalizes the algebra of real dual numbers D = R("), where "2 = 0. The Laguerre geometry over D is the geometry on the so-called Blaschke cylinder (Figure 1); the non-degenerate conics on this cylinder are called chains (or cycles, circles). If one generator of the cylinder is removed then the remaining points of the cylinder are in one-one correspon- dence (via a stereographic projection) with the points of the plane of dual numbers, which is an isotropic plane; the chains go over R" to circles and non-isotropic lines. So the point space of the chain geometry over the real dual numbers can be considered as an affine plane with an extra “improper line”. The Laguerre geometry based on L has as point set the projective line P(L) over L. It can be seen as the real affine 3-space on L together with an “improper affine plane”. There is a point model R for this geometry, like the Blaschke cylinder, but it is more compli- cated, and belongs to a 7-dimensional projective space ([6, p. -

Squaring the Circle a Case Study in the History of Mathematics the Problem

Squaring the Circle A Case Study in the History of Mathematics The Problem Using only a compass and straightedge, construct for any given circle, a square with the same area as the circle. The general problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given figure is known as the Quadrature of that figure. So, we seek a quadrature of the circle. The Answer It has been known since 1822 that the quadrature of a circle with straightedge and compass is impossible. Notes: First of all we are not saying that a square of equal area does not exist. If the circle has area A, then a square with side √A clearly has the same area. Secondly, we are not saying that a quadrature of a circle is impossible, since it is possible, but not under the restriction of using only a straightedge and compass. Precursors It has been written, in many places, that the quadrature problem appears in one of the earliest extant mathematical sources, the Rhind Papyrus (~ 1650 B.C.). This is not really an accurate statement. If one means by the “quadrature of the circle” simply a quadrature by any means, then one is just asking for the determination of the area of a circle. This problem does appear in the Rhind Papyrus, but I consider it as just a precursor to the construction problem we are examining. The Rhind Papyrus The papyrus was found in Thebes (Luxor) in the ruins of a small building near the Ramesseum.1 It was purchased in 1858 in Egypt by the Scottish Egyptologist A. -

Circle Theorems

Circle theorems A LEVEL LINKS Scheme of work: 2b. Circles – equation of a circle, geometric problems on a grid Key points • A chord is a straight line joining two points on the circumference of a circle. So AB is a chord. • A tangent is a straight line that touches the circumference of a circle at only one point. The angle between a tangent and the radius is 90°. • Two tangents on a circle that meet at a point outside the circle are equal in length. So AC = BC. • The angle in a semicircle is a right angle. So angle ABC = 90°. • When two angles are subtended by the same arc, the angle at the centre of a circle is twice the angle at the circumference. So angle AOB = 2 × angle ACB. • Angles subtended by the same arc at the circumference are equal. This means that angles in the same segment are equal. So angle ACB = angle ADB and angle CAD = angle CBD. • A cyclic quadrilateral is a quadrilateral with all four vertices on the circumference of a circle. Opposite angles in a cyclic quadrilateral total 180°. So x + y = 180° and p + q = 180°. • The angle between a tangent and chord is equal to the angle in the alternate segment, this is known as the alternate segment theorem. So angle BAT = angle ACB. Examples Example 1 Work out the size of each angle marked with a letter. Give reasons for your answers. Angle a = 360° − 92° 1 The angles in a full turn total 360°. = 268° as the angles in a full turn total 360°. -

Natural Cadmium Is Made up of a Number of Isotopes with Different Abundances: Cd106 (1.25%), Cd110 (12.49%), Cd111 (12.8%), Cd

CLASSROOM Natural cadmium is made up of a number of isotopes with different abundances: Cd106 (1.25%), Cd110 (12.49%), Cd111 (12.8%), Cd 112 (24.13%), Cd113 (12.22%), Cd114(28.73%), Cd116 (7.49%). Of these Cd113 is the main neutron absorber; it has an absorption cross section of 2065 barns for thermal neutrons (a barn is equal to 10–24 sq.cm), and the cross section is a measure of the extent of reaction. When Cd113 absorbs a neutron, it forms Cd114 with a prompt release of γ radiation. There is not much energy release in this reaction. Cd114 can again absorb a neutron to form Cd115, but the cross section for this reaction is very small. Cd115 is a β-emitter C V Sundaram, National (with a half-life of 53hrs) and gets transformed to Indium-115 Institute of Advanced Studies, Indian Institute of Science which is a stable isotope. In none of these cases is there any large Campus, Bangalore 560 012, release of energy, nor is there any release of fresh neutrons to India. propagate any chain reaction. Vishwambhar Pati The Möbius Strip Indian Statistical Institute Bangalore 560059, India The Möbius strip is easy enough to construct. Just take a strip of paper and glue its ends after giving it a twist, as shown in Figure 1a. As you might have gathered from popular accounts, this surface, which we shall call M, has no inside or outside. If you started painting one “side” red and the other “side” blue, you would come to a point where blue and red bump into each other. -

10-4 Surface and Lateral Area of Prism and Cylinders.Pdf

Aim: How do we evaluate and solve problems involving surface area of prisms an cylinders? Objective: Learn and apply the formula for the surface area of a prism. Learn and apply the formula for the surface area of a cylinder. Vocabulary: lateral face, lateral edge, right prism, oblique prism, altitude, surface area, lateral surface, axis of a cylinder, right cylinder, oblique cylinder. Prisms and cylinders have 2 congruent parallel bases. A lateral face is not a base. The edges of the base are called base edges. A lateral edge is not an edge of a base. The lateral faces of a right prism are all rectangles. An oblique prism has at least one nonrectangular lateral face. An altitude of a prism or cylinder is a perpendicular segment joining the planes of the bases. The height of a three-dimensional figure is the length of an altitude. Surface area is the total area of all faces and curved surfaces of a three-dimensional figure. The lateral area of a prism is the sum of the areas of the lateral faces. Holt Geometry The net of a right prism can be drawn so that the lateral faces form a rectangle with the same height as the prism. The base of the rectangle is equal to the perimeter of the base of the prism. The surface area of a right rectangular prism with length ℓ, width w, and height h can be written as S = 2ℓw + 2wh + 2ℓh. The surface area formula is only true for right prisms. To find the surface area of an oblique prism, add the areas of the faces. -

Angles ANGLE Topics • Coterminal Angles • Defintion of an Angle

Angles ANGLE Topics • Coterminal Angles • Defintion of an angle • Decimal degrees to degrees, minutes, seconds by hand using the TI-82 or TI-83 Plus • Degrees, seconds, minutes changed to decimal degree by hand using the TI-82 or TI-83 Plus • Standard position of an angle • Positive and Negative angles ___________________________________________________________________________ Definition: Angle An angle is created when a half-ray (the initial side of the angle) is drawn out of a single point (the vertex of the angle) and the ray is rotated around the point to another location (becoming the terminal side of the angle). An angle is created when a half-ray (initial side of angle) A: vertex point of angle is drawn out of a single point (vertex) AB: Initial side of angle. and the ray is rotated around the point to AC: Terminal side of angle another location (becoming the terminal side of the angle). Hence angle A is created (also called angle BAC) STANDARD POSITION An angle is in "standard position" when the vertex is at the origin and the initial side of the angle is along the positive x-axis. Recall: polynomials in algebra have a standard form (all the terms have to be listed with the term having the highest exponent first). In trigonometry, there is a standard position for angles. In this way, we are all talking about the same thing and are not trying to guess if your math solution and my math solution are the same. Not standard position. Not standard position. This IS standard position. Initial side not along Initial side along negative Initial side IS along the positive x-axis. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

A CONCISE MINI HISTORY of GEOMETRY 1. Origin And

Kragujevac Journal of Mathematics Volume 38(1) (2014), Pages 5{21. A CONCISE MINI HISTORY OF GEOMETRY LEOPOLD VERSTRAELEN 1. Origin and development in Old Greece Mathematics was the crowning and lasting achievement of the ancient Greek cul- ture. To more or less extent, arithmetical and geometrical problems had been ex- plored already before, in several previous civilisations at various parts of the world, within a kind of practical mathematical scientific context. The knowledge which in particular as such first had been acquired in Mesopotamia and later on in Egypt, and the philosophical reflections on its meaning and its nature by \the Old Greeks", resulted in the sublime creation of mathematics as a characteristically abstract and deductive science. The name for this science, \mathematics", stems from the Greek language, and basically means \knowledge and understanding", and became of use in most other languages as well; realising however that, as a matter of fact, it is really an art to reach new knowledge and better understanding, the Dutch term for mathematics, \wiskunde", in translation: \the art to achieve wisdom", might be even more appropriate. For specimens of the human kind, \nature" essentially stands for their organised thoughts about sensations and perceptions of \their worlds outside and inside" and \doing mathematics" basically stands for their thoughtful living in \the universe" of their idealisations and abstractions of these sensations and perceptions. Or, as Stewart stated in the revised book \What is Mathematics?" of Courant and Robbins: \Mathematics links the abstract world of mental concepts to the real world of physical things without being located completely in either".