Elections in Wartime: the Syrian People's Council (2016-2020)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: "Torture Was My Punishment": Abductions, Torture and Summary

‘TORTURE WAS MY PUNISHMENT’ ABDUCTIONS, TORTURE AND SUMMARY KILLINGS UNDER ARMED GROUP RULE IN ALEPPO AND IDLEB, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Cover photo: Armed group fighters prepare to launch a rocket in the Saif al-Dawla district of the Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons northern Syrian city of Aleppo, on 21 April 2013. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/4227/2016 July 2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 METHODOLOGY 7 1. BACKGROUND 9 1.1 Armed group rule in Aleppo and Idleb 9 1.2 Violations by other actors 13 2. ABDUCTIONS 15 2.1 Journalists and media activists 15 2.2 Lawyers, political activists and others 18 2.3 Children 21 2.4 Minorities 22 3. -

Local Elections: Is Syria Moving to Reassert Central Control?

RESEARCH PROJECT REPORT FEBRUARY 2019/03 RESEARCH PROJECT LOCAL REPORT ELECTIONS: IS JUNE 2016 SYRIA MOVING TO REASSERT CENTRAL CONTROL? AUTHORS: AGNÈS FAVIER AND MARIE KOSTRZ © European University Institute,2019 Content© Agnès Favier and Marie Kostrz, 2019 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions, Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2019/03 February 2019 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Local elections: Is Syria Moving to Reassert Central Control? Agnès Favier and Marie Kostrz1 1 Agnès Favier is a Research Fellow at the Middle East Directions Programme of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. She leads the Syria Initiative and is Project Director of the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project. Marie Kostrz is a research assistant for the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project at the Middle East Directions Programme. This paper is the result of collective research led by the WPCS team. 1 Executive summary Analysis of the local elections held in Syria on the 16th of September 2018 reveals a significant gap between the high level of regime mobilization to bring them about and the low level of civilian expectations regarding their process and results. -

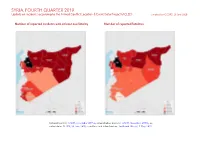

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Pdf | 548.22 Kb

NEPAL’S NEW ALLIANCE: THE MAINSTREAM PARTIES AND THE MAOISTS Asia Report N°106 – 28 November 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. THE PARTIES................................................................................................................ 3 A. OUTLOOK .............................................................................................................................3 B. IMPERATIVES ........................................................................................................................4 C. INTERNAL TENSIONS AND CONSTRAINTS ..............................................................................5 D. PREPARATION FOR TALKS .....................................................................................................7 III. THE MAOISTS .............................................................................................................. 8 A. OUTLOOK .............................................................................................................................8 B. IMPERATIVES ........................................................................................................................9 C. INTERNAL TENSIONS AND CONSTRAINTS ............................................................................10 D. PREPARATION FOR TALKS -

The Communist Party Sweden

INTERNATIONAL GUESTS GREETING MESSAGES 18 TH CONGRESS OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY SWEDEN Guests and Greetings from Costa Rica, Cuba, Czech Republik, Denmark, El Salvador, France, Guatemala, Honduras, DPR Korea, Lao PDR, Norway, Palestine, Philippines, Poland, Schwitzerland, Spain, Sri Lanka, Syria, US, Venezuela, Vietnam and WFTU All international guests were welcome on stage at the first day of the congress. International guests and greeting messages The Communist Party, Sweden, has friends Cuba: Embassy of Cuba all over the world. It was clearly visible on Denmark : Danish Communist Party at the 18 th congress 5-7 th of January 2017 El Salvador : Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN) with many international guests present and France : Pole of Communist Revival in France, many greeting messages sent to the con - PRCF gress. DPR Korea: Embassy of DPR Korea 13 international delegations attended the congress in Laos : Embassy of Lao PDR Göteborg. They were representing organizations in Palestine : Popular Front for the Liberation of twelve countries in Europe, Middle East, Asia and Palestine (PFLP) South and Central America. Philippines : National Democratic Front (NDF) Among the guests were Communists, anti-imperi - Sri Lanka : People's Liberation Front (JVP) alists and other forces that play a progressive role in Syria: Syrian Communist Party (United) their countries. Like British Trade Unionists Against UK : Trade Unionists Against the EU the EU which for decades has worked for Britain to Venezuela: Embassy of Bolivarian republic of leave the EU and in the referendum in June last year Venezuelan was on the winning side. In addition to organizations that the guests represent, The following international guests were present in the Communist Party received greetings from seve - the congress premises in Göteborg: ral organizations from all over the world. -

Week 46, 10 – 16 November 2017

Week 46, 10 – 16 November 2017 General developments & political & security situation • US-led Coalition’s air force killed civilians and some paramedics in Tal Ash-Shayer area of Al-Duaiji village in rural Deir Ez-Zor, on the Syrian-Iraqi border. • Russian and US Presidents affirmed their commitment to Syria’s sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity; stressing that political settlement of the crisis would take place within framework of the Geneva process - in a joint statement issued on sidelines of the APEC summit in Vietnam. • Trump says U.S. deal with Russia on Syria will save many lives. • Moscow: Conclusions of the report of the UN-OPCW Joint Investigative Mission (JIM) on allegations of Syrian government's use of sarin gas had no basis. • Russian Defense: Russian experts are contributing to clearance of mines, left behind by ISIS, in Abu Kamal. • Zakharova: Syria's national dialogue conference is under preparation. • Algerian Prime Minister stressed that some countries in the region spent $ 130 billion to destroy Syria, Libya and Yemen. • Chinese Ambassador in Damascus stressed that a Syrian-Syrian dialogue, that guaranteed political solution, was the only way to end the crisis. • The United States has no plans to carry out military patrolling in Syria's de-escalation zones, US Defense Secretary Jim Mattis said. • The Syrian army, with support from the Russian Aerospace Forces, has recently retaken the city of Abu Kemal, the last ISIS stronghold in the eastern Syrian governorate of Deir Ezzor. • ISIS militants regained control of Abu Kemal, their last stronghold in Syria, after Iranian-backed militias who claimed to have captured the city a few days earlier. -

Iraq's Muqtada Al-Sadr

IRAQ’S MUQTADA AL-SADR: SPOILER OR STABILISER? Middle East Report N°55 – 11 July 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. MUQTADA’S LINEAGE .............................................................................................. 1 A. MUHAMMAD BAQIR AL-SADR: THE REVOLUTIONARY THINKER AND “FIRST MARTYR” ......2 B. MUHAMMAD SADIQ AL-SADR: THE PLEBEIAN ACTIVIST AND “SECOND MARTYR”............3 C. MUQTADA AL-SADR: THE UNLIKELY HEIR .........................................................................6 II. MUQTADA’S STEEP AND SWIFT LEARNING CURVE....................................... 7 A. FROM CONFRONTATION TO DOMINANT PRESENCE................................................................7 B. TRIAL AND ERROR: THE FAILURE AND LESSONS OF RADICALISATION ................................10 C. MUQTADA’S POLITICAL ENTRY ..........................................................................................12 III. THE SADRIST MOVEMENT: AN ATYPICAL PHENOMENON ....................... 17 A. MUQTADA’S POLITICAL RESOURCES...................................................................................17 B. AN UNSTRUCTURED MOVEMENT ........................................................................................20 IV. THREE POTENTIAL SOURCES OF CONFLICT ................................................. 21 V. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 24 APPENDICES A. MAP OF IRAQ ......................................................................................................................25 -

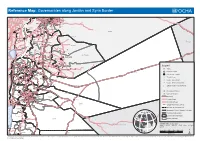

Reference Map: Governorates Along Jordan and Syria Border

Reference Map:] Governorates along Jordan and Syria Border Qudsiya Yafur Tadmor Sabbura Damascus DAMASCUS Obada Nashabiyeh Damascus Maliha Qisa Otayba Yarmuk Zabadin Deir Salman Madamiyet ElshamDarayya Yalda Shabaa Haran Al'awameed Qatana Jdidet Artuz Sbeineh Hteitet Elturkman LEBONAN Artuz Sahnaya Buwayda ] Hosh Sahya Jdidet Elkhas A Tantf DarwashehDarayya Ghizlaniyyeh Khan Elshih Adleiyeh Deir Khabiyeh MqeilibehKisweh Hayajneh Qatana ZahyehTiba Khan Dandun Mazraet Beit Jin Rural Damascus Sa'sa' Hadar Deir Ali Kanaker Duma Khan Arnaba Ghabagheb Jaba Deir Elbakht SYRIA Quneitra Kafr Shams Aqraba Jbab Nabe Elsakher Quneitra As-Sanamayn Hara As-Sanamayn IRAQ Nimer Ankhal Qanniyeh I Jasim Shahba Mahjeh S Nawa Shaqa R Izra' Izra' Shahba Tassil Sheikh Miskine Bisr Elharir A Al Fiq Qarfa Nemreh Abtaa Nahta E Ash-Shajara As-Sweida Da'el Alma Hrak Western Maliha Kherbet Ghazala As-Sweida L Thaala As-Sweida Saham Masad Karak Yadudeh Western Ghariyeh Raha Eastern Ghariyeh Um Walad Bani kinana Kharja Malka Torrah Al'al Mseifra Kafr Shooneh Shamaliyyeh Dar'a Ora Bait Ras Mghayyer Dar'a Hakama ManshiyyehWastiyya Soom Sal Zahar Daraa] Dar'a Tiba Jizeh Irbid Boshra Waqqas Ramtha Nasib Moraba Legend Taibeh Howwarah Qarayya Sammo' Shaikh Hussein Aidoon ! Busra Esh-Sham Arman Dair Abi Sa'id Irbid ] Milh AlRuwaished Salkhad Towns Kofor El-Ma' Nassib Bwaidhah Salkhad Mazar Ash-shamaliCyber City Mghayyer Serhan Mashari'eKora AshrafiyyehBani Obaid ! National Capital Kofor Owan Badiah Ash-Shamaliyya Al_Gharbeh Rwashed Kofor Abiel NULL Ketem ! Jdaitta No'ayymeh -

Syrian Muslim Brotherhood Still a Crucial Actor. Inclusivity the Order of the Day in Dealings with Syria's Opposition

Introduction Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik ments German Institute for International and Security Affairs m Co Syrian Muslim Brotherhood Still a Crucial Actor WP S Inclusivity the Order of the Day in Dealings with Syria’s Opposition Petra Becker Summer 2013 brought severe setbacks for the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood. Firstly, one of its most important regional supporters, Qatar lost its leading role in the Group of Friends of the Syrian People, the alliance of states and organisations backing Syria’s opposition, to Saudi Arabia. Secondly, the Brotherhood has been hit by stinging criti- cism of the Egyptian MB’s performance in government and the media witch-hunt against political Islam following the ouster of Mohammed Morsi. In the face of these events the Syrian Brotherhood – to date still a religious and social movement – post- poned the founding of a political party planned for late June. Thirdly, the Brotherhood – like its partners in the National Coalition which opposes the Syrian regime – bet on an American-backed military intervention in August/September. This intervention did not occur due to the American-Russian brokered agreement providing for Syria to join the Convention on the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. As a result, the National Coalition and its Supreme Military Command have faced defections of major rebel forces, which may lead to a major shift towards Jihadi Salafism and the marginalization of moderate forces on the ground. Yet the Brother- hood remains the best-organised political force within the Syrian opposition alliances and still sees itself becoming the leading force in post-revolutionary Syria. Germany and Europe should encourage moderate forces whatever their political colours and foster the implementation of democratic concepts. -

Pamela Murgia

“TESIS” — 2018/8/31 — 9:22 — page i — #1 Hamas’ Statements A discourse analysis approach Pamela Murgia TESI DOCTORAL UPF / ANY 2018 DIRECTOR DE LA TESI Prof. Teun A. van Dijk (Universitat Pompeu Fabra), Prof. Nicola Melis (Università degli Studi di Cagliari) Departament Traducció i Ciències del Llenguatge “TESIS” — 2018/8/31 — 9:22 — page ii — #2 “TESIS” — 2018/8/31 — 9:22 — page iii — #3 Abstract Hamas, acronym for Islamic Resistance Movement, is a political movement that was founded in 1987 and has, since 2007, been in charge of the Gaza Strip. The movement was initially characterised by a language accentuated by tropes of po- litical Islam and, after the Oslo Accords, by a strong rejection of the institutions established by the Accords. Consequently, the movement refused to take part in the elections of the Palestinian Authority. The failure of the Accords in the early 2000s led the movement to take a turn, deciding to participate in the elec- tions. Hamas thus underwent a significant political development, that resulted in changes in rhetoric, ideological representations, and self-representation. The present work aims to study the movements ideological development and commu- nication strategies by the means of Discourse Analysis, with the analysis of the corpora of bayan¯ at¯ , the official statements issued by Hamas and published on their official website. Resumen Hamas, acrónimo de “Movimiento de Resistencia Islámica”, es un movimiento político que se fundó en 1987 y que desde 2007 controla la Franja de Gaza. El movimiento se caracterizó inicialmente por un lenguaje fuertemente marcado por los topoi del Islam político y, después de los Acuerdos de Oslo, por un rechazo radical de las instituciones resultado de los mismos Acuerdos. -

From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund

7/2019 From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund PUBLISHED BY THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS | UI.SE Abstract The Russian-Syrian relationship turns 75 in 2019. The Soviet Union had already emerged as Syria’s main military backer in the 1950s, well before the Baath Party coup of 1963, and it maintained a close if sometimes tense partnership with President Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000). However, ties loosened fast once the Cold War ended. It was only when both Moscow and Damascus separately began to drift back into conflict with the United States in the mid-00s that the relationship was revived. Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Russia has stood by Bashar al-Assad’s embattled regime against a host of foreign and domestic enemies, most notably through its aerial intervention of 2015. Buoyed by Russian and Iranian support, the Syrian president and his supporters now control most of the population and all the major cities, although the government struggles to keep afloat economically. About one-third of the country remains under the control of Turkish-backed Sunni factions or US-backed Kurds, but deals imposed by external actors, chief among them Russia, prevent either side from moving against the other. Unless or until the foreign actors pull out, Syria is likely to remain as a half-active, half-frozen conflict, with Russia operating as the chief arbiter of its internal tensions – or trying to. This report is a companion piece to UI Paper 2/2019, Russia in the Middle East, which looks at Russia’s involvement with the Middle East more generally and discusses the regional impact of the Syria intervention.1 The present paper seeks to focus on the Russian-Syrian relationship itself through a largely chronological description of its evolution up to the present day, with additional thematically organised material on Russia’s current role in Syria. -

Steven Isaac “The Ba'th of Syria and Iraq”

Steven Isaac “The Ba‘th of Syria and Iraq” for The Encyclopedia of Protest and Revolution (forthcoming from Oxford University Press) Three main currents of socialist thought flowed through the Arab world during and after World War II: The Ba‘th party’s version, that of Nasser, and the options promulgated by the region’s various communist parties. None of these can really be considered apart from the others. The history of Arab communists is often a story of their rivalry and occasional cohabitation with other movements, so this article will focus first on the Ba‘th and then on Nasser while telling the story of all three. In addition, the Ba‘th were active in more places than just Syria and Iraq, although those countries saw their most signal successes (and concomitant disappointments). Michel Aflaq, a Sorbonne-educated, Syrian Christian, was one of the two primary founders of the Ba‘th (often transliterated as Baath or Ba‘ath) movement. His exposure to Marx came during his studies in France, and he associated for some time with the communists in Syria after his return there in 1932. He later declared his fascination with communism ended by 1936, but others cite him as still a confirmed party member until 1943. His co-founder, Salah al-Din al-Bitar, likewise went to France for his university education and returned to Syria to be a teacher. Frustrated by France’s inter-war policies, the nationalism of both men came to so influence their attitudes towards the West that even Western socialism became another form of imperialism.