Full Articles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

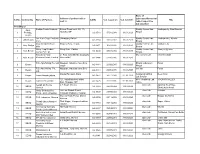

S.L.No. Commodity Name of Packers Address of Packers with E- Mail Id

Name of Address of packers with e- Laboratory/Comercial S.l.No. Commodity Name of Packers CA No. C.A. issued on C.A. valid till TBL mail id /SGL/Cooperative Lab attached R.O.Bhopal Aata, Poddar Foods Products Behind Rewa hotel, NH- 78, Quality Control Lab Vindhyavelly, Maa Birasani 1 Porridge, Shahdol, MP A/2 3518 07.08.2018 31.03.2023 Bhopal Besan Lav Kush Corp. Products Gairatganj, Raisen Quality Control Lab Vindhya velly, Ajiveka 2 Atta Besan A/2-3384 11.10.2013 31.03.2023 Com. Bhopal Maa GAYATRI Flour Khajuria Bina, Dewas Quality control Lab, Vindya Velly 3 Atta, Daliya A/2 3471 15.09.2016 31.03.2021 Mills Bhopal Sironj Crop Produce Sironj Distt- Vidisha Quality Control Lab Sironj & Ajjevika 4 Atta, Besan A/2-3404 03.03.2014 31.03.2019 Comp. Pvt. Ltd Bhopal Kaila Devi Food 21 Ram Janki Mandir Jiwajiganj Morena Ana Lab Chambal Gold 5 Atta, Besan Products Private Limited Morena MP A/2 3464 22/06/2016 31.03.2021 R.B. Agro Milling Pvt. Ltd. Naugaon Industries Area Bina, Bhopal Laboratory Paras 6 Besan A/2-3444 26/06/2015 31/03/2020 Sagar Bhopal R.B. Agro Milling Pvt. Naugoan, Industrial area,Bina own lab Paras 7 Besan A/2-3444 29.05.2015 31.03.2020 Ltd. Mauza Ramgarh, Datia Gwaliar Analytical Deep Gold 8 Besan Tiwari Masala Udyog A/2 3477 14.12.2016 31..03.2021 Lab,Gwaliar 121, Industrial Area, Maksi, MPP. Analytical Lab VINDHYA VALLEY 9 Besan Lakshmi Besan Mill A/2 3476 20.10.2016 31..03.2021 Distt. -

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

NW-77 FINAL FSR Pazhyar

Preface India is the largest peninsula in the world with a coastline of about 7517 km with 12 major ports and 185 non major / intermediate ports with a very impressive water network consisting of rivers, lakes, creeks and canals. An efficient transport sector is vital for development of the economy to stimulate optimum competitive business environment. Indian transport system comprises various modes, viz. Railways, Roadways, Inland Waterways, Coastal Shipping and Airways. Integrated development of waterways can generate waterway grid that may in future help shift cargo traffic from road transport to the cheaper and eco-friendly inland waterways. The first national waterways were established in India in mid 1980s & 1993 with a combined length of 2,716 km: NW 1 (1620 km): Ganga - Bhagirathi- Hooghly river system between Haldia & Allahabad declared as National waterway in 1986 NW 2 (891 Km): Brahmaputra River between Bangladesh Border and Sadiya declared as National waterway in 1988 NW 3 (205 km): West coast canal (168 km) – Udyog mandal canal (23 km) - Champakara canal (14 km) declared as National waterway in 1993 The government also declared the following two inland waterways as national waterways during 2008: NW 4 (1095 km): Kakinada-Pondicherry canal - Godavari and Krishna rivers NW 5 (623 km): East Coast Canal - Brahmani River and Mahanadi delta Given the untapped potential of India’s inland waterways, the Govt. of India desires to explore the commercial navigation potential on year round basis. Ministry of Shipping (MoS), Govt. of India has directed Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) to identify the viable waterways in India for their phased development. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Kanyakumari District Statistical Handbook – 2016

Kanyakumari District Statistical Handbook – 2016 Preface Salient Features District Profile 1. Area &Population 2. Climate & Rainfall 3. Agriculture 4. Irrigation 5. Animal Husbandary 6. Banking & Insurance 7. Co-Operative Societies 8. Civil Supplies 9. Communications 10. Electricity 11. Education 12. Fisheries 13. Handloom 14. Handicrafts 15. Health & Family Welfare 16. Housing 17. Industries 18. Factories 19. Local Bodies 20. Labour & Employment 21. Legal services 22. Libraries 23. Mining & Quarrying 24. Manufacturing 27. Non-Conventional 25. Medical Services 26. Motor Vehicles Energy 28. Police & Prison 29. Public Health 30. Printing & Publications 31. Prices Indices 32. Quality Control 33. Registration 36. Recreation & Cultural 34. Repair & Services 35. Restaurants & Hotels Services 39. Scientific Research 37. Social Welfare 38. Sanitary Services Services 40. Storage Facilities 41. Textiles 42. Trade & Commerce 43. Transport 44. Tourism 45. Vital Statistics 46. Voluntary Services 47. Waterworks & Supply 48. Rubber Study DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF STATISTICS KANNIYAKUMARI DISTRICT PREFACE The District Statistical Hand Book is prepared and published by our Department every year. This book provides useful data across various departments in Kanniyakumari District. It contains imperative and essential statistical data on different Socio-Economic aspects of the District in terms of statistical tables and graphical representations. This will be useful in getting a picture of Kanniyakumari’s current state and analyzing what improvements can be brought further. I would liketo thank the respectable District Collector Sh. SAJJANSINGH R CHAVAN, IAS for his cooperation in achieving the task of preparing the District Hand Book for the year 2015-16 and I humbly acknowledge his support with profound gratitude. The co-operation extended by the officers of this district, by supplying the information presented in this book is gratefully acknowledged. -

Electoral College As on 31-03-2018

ELECTORAL COLLEGE AS ON 31-03-2018 S. No. STATE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 MOBILE EMAIL YEMMIGANUR ROAD, ADONI, ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH ADONI Dr. K. KRISHNADEVARAYALU C/O DEVI NURSING HOME, PRADESH. 1 1-3A ASHA HYOTHI ADARASHNAGAR, ANDHRA PRADESH AKIVIDU Dr. BABU ISAAC VICTOR DEVARAPALLI ANDHRA PRADESH - 534235. AKIVIDU W.GODAVARY, 2 9441554301 ANDHRA PRADESH ANAKAPALLY Dr. NAIDU D.DORAMMA NARASINGARAO PET, ANAKAPALLY POST, VIZAG DT.-1, ANDHRA PRADESH. 3 ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTHAPUR Dr. A. KESANNA 15/382 KAMLA NAGAR, ANANTAPUR, ANDHRA PRADESH. - 515001 [email protected] 4 9440285110 ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTHAPUR Dr. K.S.S.VENKATESWARA RAO D.NO.12-631/A,JESUS NAGAR ANANTHAPUR,, ANDHRA PRADESH. - 515001 5 ANDHRA PRADESH ANAPARTHY Dr. A. SATYA NARAYANA MURTHY SRI VANKATESWARA NURSING HOME, ANAPARTHY, ANDHRA PRADESH - 500042 [email protected] 6 9491386215 SATYADEVI POORNA NURSING HOME, ANDHRA PRADESH APPA Dr. D. VENKATA CHALAPATI RAO W.G.DIST., ANDHRA PRADESH - 534230 [email protected] VENDRA 7 9395121748 HOTEL SAROVAR ROAD BHIMAVARAM SHANTI NURSING HOME, J.P. ROAD, HOTEL ANDHRA PRADESH BHIMAVARAM Dr. HARIS CHANDRA PRASAD N 534202 ANDHRA PRADESH, ANDHRA [email protected] SAROVAR ROAD PRADESH - 534239 8 9885886640 ASWANI NURSING HOME, HOTEL SAROVAR J.P. ROAD, BHIMAVARAM 534202 ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH BHIMAVARAM Dr. RANGA RAO MELAM ROAD, PRADESH., ANDHRA PRADESH - 534201 9 ANDHRA PRADESH BOBBILI Dr. MURTY M.SATYANARAYANA CIVIL SURGEON, HOSPITAL ROAD, , BOBBILI, ANDHRA PRADESH - 532558 10 JANAKI NURSING HOME, BHASKAR THEATRE , CHILAKALURIPET, ANDHRA PRADESH - ANDHRA PRADESH CHILAKALURIPET Dr. M. HANUMMANTHA RAO [email protected] CENTRE, 522616 11 9848350255 ANDHRA PRADESH CHITTOOR Dr. N. -

Kanyakumari District

Kanyakumari District Statistical Handbook 2010-11 1. Area & Population 2. Climate & Rainfall 3. Agriculture 4. Irrigation 5. Animal Husbandary 6. Banking & Insurance 7. Co-operation 8. Civil Supplies 9. Communications 10. Electricity 11. Education 12. Fisheries 13 Handloom 14. handicrafts 15. Health & Family Welfare 16. Housing 17. Industries 18. Factories 19. Legal Bodies 20. Labour&Employment 21. Legal Services 22. Libraries 23. Mining & Quarrying 24. Manufacturing 25. Medical services 26 Motor Vehicles 27. NonConventional Energy 28. Police & Prison 29. Public Health 30. Printing & publication 31. Price Indices. 32. Quality Control 33. Registration 34. Repair & Services 35. Restaurents & Hotels 36. Recreation 37. Social Welfare 38. Sanitary services 39. Scientific Research 40. Storage Facilities 41 Textiles 42. Trade & Commerce 43. Transport 44. Tourism 45. Birth & Death 46.Voluntary Services 47. Waterworks & Supply 1 1.AREA AND POPULATION 1.1 AREA, POPULATION, LITERATES, SC, ST – SEXWISE BY BLOCKS YEAR: 2010-2011 Population Literate Name of the Blocks/ Sl.No. Municipalities Male Male Female Female Persons Persons Area (sq.km) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 Agastheswaram 133.12 148419 73260 75159 118778 60120 58658 2 Rajakkamangalam 120.16 137254 68119 69135 108539 55337 53202 3 Thovalai 369.07 110719 55057 55662 85132 44101 41031 4 Kurunthancode 106.85 165070 81823 83247 126882 64369 62513 5 Thuckalay 130.33 167262 82488 84774 131428 66461 64967 6 Thiruvattar 344.8 161619 80220 81399 122710 62524 60186 7 Killiyoor 82.7 156387 78663 77724 119931 -

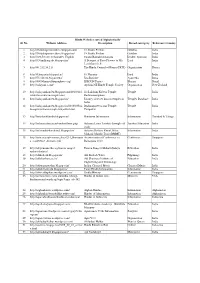

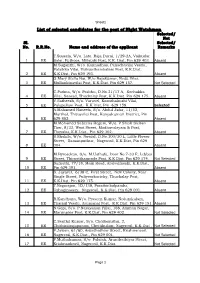

List of Selected Candidates for the Post of Night Watchman Selected/ Not Sl

Sheet1 List of selected candidates for the post of Night Watchman Selected/ Not Sl. Selected/ No. R.R.No. Name and address of the applicant Remarks T.Suseela, W/o. Late. Raja Durai, 1/29-2A, Vaikudar 1 EE Salai, Puthoor, Mylaudy Post, K.K. Dist, Pin 629 403. Absent M.Suganthi, W/o. Kannadhas, Panachavilai Veedu, Palaikka Vilai, Vizhunthambalam Post, K.K.Dist, 2 EE K.K.Dist, Pin 629 193. Absent G.Mary Stella Bai, W/o.Rajakumar, Nedu Vilai, 3 EE Mullankinavilai Post, K.K.Dist. Pin 629 157. Not Selected C.Padma, W/o. Prabhu, D.No.31/17 A, Kochakka 4 EE Vilai, Saroad, Thuckalay Post, K.K.Dist. Pin 629 175. Absent V.Satheesh, S/o. Varuvel, Koonthakuzhi Vilai, 5 EE Palapallam Post, K.K.Dist, Pin 629 159. Selected A.Mohamed Haneefa, S/o. Abdul Jafar, 11/52, Marthal, Thittuvilai Post, Kanyakumari District, Pin 6 EE 629 852. Absent M.Mohamed Sabeena Begum, W/o. P.Sheik Sickan Ther, 8/33, West Street, Madhavalayam & Post, 7 EE Thovalai, K.K.Dist., Pin 629 302. Absent S.Shakila, W/o. Nowfal, D.No.100/30 L, Little Flower Street, Ramanputhur, Nagercoil, K.K.Dist, Pin 629 8 EE 004. Absent M.Byrosekan, S/o. M.Usthafa, Door No.7-33 F, Lebbai 9 EE Street, Thiruvithamcode Post, K.K.Dist. Pin 629 174. Not Selected Sumathi, 77/18, Main Road, Aralvaimozhi, K.K.Dist, 10 EE Pin 629 301. Absent S. Jayavel, 6/38 C, First Street, New Colony, Near Single Street, Puliyoorkurichy, Thuckalay Post, 11 EE K.K.Dist. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

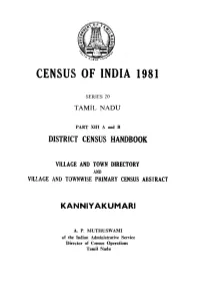

District Census Handbook, Kanniyakumari, Part XIII a and B

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 20 TAMIL NADU PART XIII A and B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY AND VILLAGE AND TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT KANNIY AKUMARI A. P. lVIUTHUSWAMI of the Indian Administrative Service Director· of Census Operations Tamil Nadu . Price: PUBL1SHED BY GOVERNMENT OF l'A,MH. NADU AND' PRINTED BY TaE DIRECTOR. OF STATIONERY AND PRINTIN<1 AT GOVeRNMENT JlRESS, MADRAS·600 G79 GONTENTS PAGES 1. Foreword iii-iv 2. Preface v-vi 3. Acknowledgement vii 4. District Map Facing P. ix S. Important Statistics ix-x 6. Analytical Note- (i) Census Concepts :-Rural and Urban Areas. Census house I household Scheduled Castes Scheduled Tribes, Literate. Main Worker, Marginal Worker, Non worker etc. 1-2 (ii) History o~ the District C~nsus Handbook including scope of Village and Town DIrectory and Pnmary Census Abstract . .. 2-6 (iii) Early history, Physic".! features, location and physiography soils, climate and rainf211, Hills, Rivers, Coastline, Geology and Minerals, Forestry, Land and Land ust: pattern, Agriculture, Irrigation and power. Animal Husbandry, Fishery, IndustrY-Medium and large industry, Cottage Industry, Trade, Transport and Communication, Social and cultural event, places of tourist interest .. 7-15 7 Brief analy~is of the Village, Town Directory and Primary Census Abstract data. 16-26 pART A-VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTOll.Y SEOTION I VILLAGE DIRECTORY Note explaining th.:: codes used in the village Direotory 29-30 1. Vilavankod Taluk (i) Taluk map .. •• Facing P. 32 (ii) Alphabetical list of Village 33 (iii) Village Directory Statement 34-37 2. Kalkulam Taluk (i) Taluk Map .. •• Facing P. -

Government of Tamil Nadu

Government of Tamil Nadu DIRECTORATE OF MINORITIES WELFARE The Ministry of Minority Affairs has introduced a scheme of Merit Cum Means Based Scholarship for students belonging to the minority communities for technical and professional courses at under-graduate and post-graduate levels during 2007-08. This is a centrally sponsored scheme, fully funded by the Central Government. The scholarship scheme has been implemented by the Government of Tamil Nadu through Directorate of Minorities Welfare,Chennai.in cordination with Tamil Nadu Minorities Economic Development Corporation. The Tamil Nadu has been forefront in impelementing various welfare programmes to Minorities. As the number of scholarships for each year is fixed and the allocation of Scholarships has been made on the basis of 2001 Census. The Institution wise students list who have awarded for this scholarships furnished hereunder for accessing to information by the students and educational institutions. The scholarship covers tuition fees and maintenance allowance maximum for 10 months only.The Educational Institutions are directed to disburse the scholalrship to the respective students within 15 days from the date of receipt of scholarship amount and to send stamped receipt to us immediately. LIST OF STUDENTS AWARDED MERIT CUM MEANS BASED SCHOLARSHIP FOR 2007-08 NAME OF THE INSTITUTE A V C COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING ,MYILADUTHURAI-609306 Dayscholar FATHER'S NAMEADDRESS / Hosteller MAINTENANCE S.NO NAME SEXM/F COURSE (D/H) TUTION ALLOWANCE TOTAL A SABEER MOHAMAD16/4,EDA St, 1 JASMINE