Best Practices Guidelines in Imaging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACR Manual on Contrast Media

ACR Manual On Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media Preface 2 ACR Manual on Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media © Copyright 2021 American College of Radiology ISBN: 978-1-55903-012-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page 1. Preface 1 2. Version History 2 3. Introduction 4 4. Patient Selection and Preparation Strategies Before Contrast 5 Medium Administration 5. Fasting Prior to Intravascular Contrast Media Administration 14 6. Safe Injection of Contrast Media 15 7. Extravasation of Contrast Media 18 8. Allergic-Like And Physiologic Reactions to Intravascular 22 Iodinated Contrast Media 9. Contrast Media Warming 29 10. Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury and Contrast 33 Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Adults 11. Metformin 45 12. Contrast Media in Children 48 13. Gastrointestinal (GI) Contrast Media in Adults: Indications and 57 Guidelines 14. ACR–ASNR Position Statement On the Use of Gadolinium 78 Contrast Agents 15. Adverse Reactions To Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media 79 16. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) 83 17. Ultrasound Contrast Media 92 18. Treatment of Contrast Reactions 95 19. Administration of Contrast Media to Pregnant or Potentially 97 Pregnant Patients 20. Administration of Contrast Media to Women Who are Breast- 101 Feeding Table 1 – Categories Of Acute Reactions 103 Table 2 – Treatment Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 105 Children Table 3 – Management Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 114 Adults Table 4 – Equipment For Contrast Reaction Kits In Radiology 122 Appendix A – Contrast Media Specifications 124 PREFACE This edition of the ACR Manual on Contrast Media replaces all earlier editions. -

"Fullness" of the Pancreas on CT. Usually Benign, but EUS Plus/Minus FNA Is Warranted to Identify Malignancy

JOP. J Pancreas (Online) 2009 Jan 8; 10(1):37-42. ORIGINAL ARTICLE Focal or Diffuse "Fullness" of the Pancreas on CT. Usually Benign, but EUS Plus/Minus FNA Is Warranted to Identify Malignancy John David Horwhat1, Henning Gerke2, Ruben Daniel Acosta1, Darren A Pavey3, Paul S Jowell3 1Gastroenterology Service, Department of Medicine, Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Washington, DC, USA. 2Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Iowa City, IA, USA. 3Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Duke University Health System. Durham, NC, USA ABSTRACT Context The role of EUS to evaluate subtle radiographic abnormalities of the pancreas is not well defined. Objective To assess the yield of EUS±FNA for focal or diffuse pancreatic enlargement/fullness seen on abdominal CT scan in the absence of discrete mass lesions. Design Retrospective database review. Setting Tertiary referral center. Patients and interventions Six hundred and 91 pancreatic EUS exams were reviewed. Sixty-nine met inclusion criteria of having been performed for focal enlargement or fullness of the pancreas. Known chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic calcifications, acute pancreatitis, discrete mass on imaging, pancreatic duct dilation (greater than 4 mm) and obstructive jaundice were excluded. Main outcome measurement Rate of malignancy found by EUS±FNA. Results FNA was performed in 19/69 (27.5%) with 4 new diagnoses of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, one metastatic renal cell carcinoma, one metastatic colon cancer, one chronic pancreatitis and 12 benign results. Eight patients had discrete mass lesions on EUS; two were cystic. All malignant diagnoses had a discrete solid mass on EUS. Conclusions Pancreatic enlargement/fullness is often a benign finding related to anatomic variation, but was related to malignancy in 8.7% of our patients (6/69). -

Coronary Artery Calcium Quantification in Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography Angiography

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Computer Science Dissertations Department of Computer Science 12-18-2013 Coronary Artery Calcium Quantification in Contrast-enhanced Computed Tomography Angiography Abinashi Dhungel Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cs_diss Recommended Citation Dhungel, Abinashi, "Coronary Artery Calcium Quantification in Contrast-enhanced Computed Tomography Angiography." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cs_diss/80 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Computer Science at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Computer Science Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORONARY ARTERY CALCIUM QUANTIFICATION IN CONTRAST-ENHANCED COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY by ABINASHI DHUNGEL Under the Direction of Dr. Michael Weeks ABSTRACT Coronary arteries are the blood vessels supplying oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscles. Coronary artery calcium (CAC), which is the total amount of calcium deposited in these arteries, indicates the presence or the future risk of coronary artery diseases. Quantification of CAC is done by using computed tomography (CT) scan which uses attenuation of x- ray by different tissues in the body to generate three-dimensional images. Calcium can be easily spotted in the CT images because of its higher opacity to x-ray compared to that of the surrounding tissue. However, the arteries cannot be identified easily in the CT images. Therefore, a second scan is done after injecting a patient with an x-ray opaque dye known as contrast material which makes different chambers of the heart and the coronary arteries visible in the CT scan. -

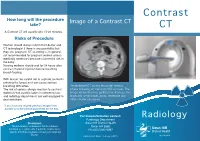

Contrast CT Take? CT a Contrast CT Will Usually Take 15-20 Minutes

Contrast How long will the procedure Image of a Contrast CT take? CT A Contrast CT will usually take 15-20 minutes. Risks of Procedure Women should always inform their doctor and CT technologist if there is any possibility that they are pregnant. CT scanning is, in general, not recommended for pregnant women unless medically necessary because of potential risk to the baby. Nursing mothers should wait for 24 hours after contrast material injection before resuming breast-feeding. With Ioscan, be careful not to aspirate (contents entering the lungs) as it can cause serious breathing difficulties. An abdomen CT during the portal-venous The risk of serious allergic reaction to contrast phase following an injection of IV contrast. The materials that contain iodine is extremely low, image shows the liver, gallbladder, kidneys, the and radiology departments are well-equipped to large and small bowel, aorta, vertebrae and deal with them. other smaller structures. If you have any related previous images from another provider please bring them on the day. For more information contact: Radiology Radiology Department Disclaimer: Swan Hill District Health The information contained in this brochure is Swan Hill 3585 intended as a guide only. If patients require more Ph: (03) 5033 9287 specific information please contact your referring Doctor. Publication Date: February 2013 What is a Contrast CT? Preparation CT scans of internal organs, bones, soft tissue Women must inform the radiographer if there is If you are over 55 years of age, your doctor will and blood vessels reveal more details than any chance that they are pregnant or if they are give you a pathology slip to have a ‘U & E’ blood regular x-rays. -

Guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media Part 1

Guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media Part 1 This part 1 comprises: 1. Prevention of post-contrast acute kidney injury 2. Use of iodine-containing contrast media in patients with diabetes type 2 who use metformin 3. Use of iodine-containing contrast media in patients undergoing dialysis INITIATED BY Radiological Society of the Netherlands IN ASSOCIATION WITH Netherlands Association of Internal Medicine Dutch Federation for Nephrology Dutch Society of Intensive Care Association of Surgeons of the Netherlands The Netherlands Society of Cardiology Dutch Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians Dutch Association of Urology Dutch Society Medical Imaging and Radiotherapy WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists FINANCED BY Quality Funds of Medical Specialists 1 Guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media – Part 1 Colophon GUIDELINE SAFE USE OF CONTRAST MEDIA – PART 1 ©2017 Radiological Society of the Netherlands Address: Taalstraat 40, 5260 CB Vught 0800 0231 536 / 073 614 1478 [email protected] www.radiologen.nl All rights reserved. The text in this publication can be copied, saved or made public in any manner: electronically, by photocopy or in another way, but only with prior permission of the publisher. Permission for usage of (parts of) the text can be requested by writing or e- mail, only form the publisher. Address and email: see above. 2 Guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media – Part 1 Index Working group ........................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1 General Introductions ............................................................................. 5 Chapter 2 Justification of this Guideline ................................................................. 10 Chapter 3 PC-AKI: Definitions, Terminology & Clinical Course.….…………….…………… 19 Chapter 4 Risk Stratification and Risk Stratification Tools ...................................... -

Saddle Pulmonary Embolism on Non-Contrast CT

Journal of Lung, Pulmonary & Respiratory Research Case Report Open Access Saddle pulmonary embolism on non-contrast CT Abstract Volume 8 Issue 2 - 2021 Background: A saddle pulmonary embolism (PE) is a large embolism that straddles the Bilal Chaudhry MD,1 Kirill Alekseyev MD, bifurcation of the pulmonary trunk. This PE extends into the right and left pulmonary MBA,2 Lidiya Didenko MS4,2 Gennadiy Ryklin arteries. There is a greater incidence in males. Common features of a PE include dyspnea, 1 1 tachypnea, cough, hemoptysis, pleuritic chest pain, tachycardia, hypotension, jugular DO, David Lee MD 1 venous distension, and severe cases Kussmaul sign. The Wells criteria for PE is used as Christiana Care Health System, USA 2Post-Acute Medical Rehabilitation Hospital of Dover, American the pretest probability. Diagnostics include D-dimer levels, CT pulmonary angiography University of Antigua, USA (CTPA), ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan), echocardiography, lower extremity venous ultrasound, chest x-ray, pulmonary angiography, and electrocardiography (ECG). Correspondence: Lidiya Didenko MS4, Post-Acute Medical Case description: We present a 65-year-old male that presented with a two-week history Rehabilitation Hospital of Dover, American University of Antigua, of dyspnea with non-radiating intermittent chest pressure. Initial V/Q scan showed a low 1240 McKee Road, Dover, DE 19904, USA, Tel (862)377-1907, Email probability for PE, but a subsequent non-contrast CT revealed that he indeed had a saddle PE. Received: May 10, 2021 | Published: May 28, 2021 Keywords: pulmonary embolism, v/q scan, CT, cor pulmonale, COPD, obstructive sleep apnea Abbreviations: PE, pulmonary embolism; V/Q scan, intermittent chest pressure in the retrosternal area without radiation. -

Ultra-Low Dose Contrast CT Pulmonary Angiography in Oncology Patients Using a High-Pitch Helical Dual-Source Technology

Diagn Interv Radiol 2019; 25:195–203 CARDIOVASCULAR IMAGING © Turkish Society of Radiology 2019 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Ultra-low dose contrast CT pulmonary angiography in oncology patients using a high-pitch helical dual-source technology Prabhakar Rajiah PURPOSE Leslie Ciancibello We aimed to determine if the image quality and vascular enhancement are preserved in com- Ronald Novak puted tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) studies performed with ultra-low contrast and optimized radiation dose using high-pitch helical mode of a second generation dual source Jennifer Sposato scanner. Luis Landeras METHODS Robert Gilkeson We retrospectively evaluated oncology patients who had CTPA on a 128-slice dual-source scan- ner, with a high-pitch helical mode (3.0), following injection of 30 mL of Ioversal at 4 mL/s with body mass index (BMI) dependent tube potential (80–120 kVp) and current (130–150 mAs). At- tenuation, noise, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) were measured in multiple pulmonary arteries. Three independent readers graded the images on a 5-point Likert scale for central vascular en- hancement (CVE), peripheral vascular enhancement (PVE), and overall quality. RESULTS There were 50 males and 101 females in our study. BMI ranged from 13 to 38 kg/m2 (22.8±4.4 kg/m2). Pulmonary embolism was present in 29 patients (18.9%). Contrast enhancement and SNR were excellent in all the pulmonary arteries (395.3±131.1 and 18.3±5.7, respectively). Image quality was considered excellent by all the readers, with average reader scores near the highest possible score of 5.0 (CVE, 4.83±0.48; PVE, 4.68±0.65; noise/quality, 4.78±0.47). -

Computed Tomography for Diagnosing Pulmonary Embolism

Computed Tomography for Diagnosing Pulmonary Embolism A Health Technology Assessment The Health Technology Assessment Unit, University of Calgary March 21, 2017 1 Acknowledgements This report is authored by Laura E. Dowsett, Fiona Clement, Vishva Danthurebandara, Diane Lorenzetti, Kelsey Brooks, Dolly Han, Gail MacKean, Fartoon Siad, Tom Noseworthy and Eldon Spackman on behalf of the HTA Unit at the University of Calgary. Dr. Eldon Spackman has received personal non-specific financial compensation from Roboleo & Co and Astellas Pharma. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interests. This research was supported by the Health Technology Review (HTR), Province of BC. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Government of British Columbia, the British Columbia Health Authorities, or any other agency. We gratefully acknowledge the valuable contributions of the key informants and thank them for their support. We also acknowledge the collaboration with CADTH to complete the cost- effectiveness model. 2 Contents Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. 7 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 8 1 Purpose of this Health Technology Assessment ................................................................... 12 2 Research Question and Research Objectives ....................................................................... -

Uroradiology for Medical Students

Uroradiology For Medical Students Lesson 7 Computerized Tomography – 1 American Urological Association Objectives • In this lesson you will learn – How computerized tomography (CT) is performed – How to read CT images – How contrast media can enhance CT scans • Plus – You will learn about three conditions for which CT imaging is useful. We’re not going to spoil the surprise by mentioning them here, but we expect you to know them by the time you complete this tutorial. Introduction • You’ve seen how ultrasound, cystography and nuclear renography allow us to see the urinary tract in unique ways. Ultrasound gives detailed images of the kidney, but tells us nothing about renal function. Nuclear renography accurately measures renal function and drainage, but the images are low resolution. CT gives us both detailed images and also an accurate representation of renal function. Case History • 47 year old female bank president presented to the ER with a history of 5 days of worsening intermittent sharp L flank pain and nausea with gross hematuria – Past history: recurrent urinary tract infections and kidney stones • Exam- afebrile, BP = 116/76, P = 115 – Abdomen: L flank pain on palpation but no guarding or rebound tenderness – Urinalysis: Many RBCs, 5-10 WBCs/hpf, - nitrites Evaluation? • Urinalysis shows some RBCs and WBCs, but no bacteria, and she is afebrile • History of stones raises the possibility of recurrence • She could have both infection and a stone. Can the two conditions be related? If she had an obstructing kidney stone with infection in the kidney, she’d be at high risk for sepsis. -

Dual-Energy Computed Tomography of the Liver: Uses in Clinical Practices and Applications

diagnostics Review Dual-Energy Computed Tomography of the Liver: Uses in Clinical Practices and Applications Masakatsu Tsurusaki 1,* , Keitaro Sofue 2 , Masatoshi Hori 2 , Kosuke Sasaki 3, Kazunari Ishii 1 , Takamichi Murakami 2 and Masatoshi Kudo 4 1 Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Kindai University, Osakasayama 589-8511, Japan; [email protected] 2 Department of Radiology, Graduate School of Medicine, Kobe University, Kobe 650-0017, Japan; [email protected] (K.S.); [email protected] (M.H.); [email protected] (T.M.) 3 CT Research Group, GE Healthcare Japan, Hino 191-8503, Japan; [email protected] 4 Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Kindai University, Faculty of Medicine, Osakasayama 589-8511, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-72-366-0221 (ext. 3133); Fax: +81-72-367-1685 Abstract: Dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) is an imaging technique based on data acqui- sition at two different energy settings. Recent advances in CT have allowed data acquisitions and simultaneous analyses of X-rays at two energy levels, and have resulted in novel developments in the field of abdominal imaging. The use of low and high X-ray tube voltages in DECT provide fused images that improve the detection of liver tumors owing to the higher contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) of the tumor compared with the liver. The use of contrast agents in CT scanning improves image quality by enhancing the CNR and signal-to-noise ratio while reducing beam-hardening artifacts. DECT can improve detection and characterization of hepatic abnormalities, including mass lesions. -

Prevention of Contrast Induced Nephropathy

Consensus Guidelines for the Prevention of Contrast Induced Nephropathy The standards of the Canadian Association of Radiologists (CAR) are not rules, but are guidelines that attempt to define principles of practice that should generally produce radiological care. The physician and medical physicist may modify an existing standard as determined by the individual patient and available resources. Adherence to CAR standards will not assure a successful outcome in every situation. The standards should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of other methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The standards are not intended to establish a legal standard of care or conduct, and deviation from a standard does not, in and of itself, indicate or imply that such medical practice is below an acceptable level of care. The ultimate judgment regarding the propriety of any specific procedure or course of conduct must be made by the physician and medical physicist in light of all circumstances presented by the individual situation. Approved: June 17, 2011 Owen RJ, Hiremath S, Myers A, Fraser-Hill M, Barrett B. Tel.: 613 860-3111 Fax: 613 860-3112 310-377 Dalhousie Street, Ottawa, Ontario K1N 9N8 CANADA www.car.ca [email protected] Canadian Association of Radiologists Abstract The development of contrast induced nephropathy (CIN), also referred to as contrast induced acute kidney injury (CI- AKI) is a significant complication of intravascular contrast medium (CM) use which is linked with excess morbidity and mortality. The increasing use of CM, an aging population and an increase in chronic kidney disease (CKD) will result in an increased incidence of contrast induced nephropathy (CIN) unless effective preventative measures are used. -

ACR Manual on Contrast Media (2020)

ACR Manual On Contrast Media 2020 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media Preface 2 ACR Manual on Contrast Media 2020 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media © Copyright 2020 American College of Radiology ISBN: 978-1-55903-012-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page 1. Preface 1 2. Version History 2 3. Introduction 4 4. Patient Selection and Preparation Strategies Before Contrast 5 Medium Administration 5. Safe Injection of Contrast Media 14 6. Extravasation of Contrast Media 18 7. Allergic-Like And Physiologic Reactions to Intravascular 22 Iodinated Contrast Media 8. Contrast Media Warming 29 9. Post-Contrast Acute Kidney Injury and Contrast-Induced 33 Nephropathy in Adults 10. Metformin 45 11. Contrast Media in Children 48 12. Gastrointestinal (GI) Contrast Media in Adults: Indications and 56 Guidelines 13. ACR–ASNR Position Statement On the Use of Gadolinium 78 Contrast Agents 14. Adverse Reactions To Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media 79 15. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) 83 16. Ultrasound Contrast Media 92 17. Treatment of Contrast Reactions 95 18. Administration of Contrast Media to Pregnant or Potentially 97 Pregnant Patients 19. Administration of Contrast Media to Women Who are Breast- 101 Feeding Table 1 – Categories Of Acute Reactions 103 Table 2 – Treatment Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 105 Children Table 3 – Management Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 114 Adults Table 4 – Equipment For Contrast Reaction Kits In Radiology 122 Appendix A – Contrast Media Specifications 124 PREFACE This edition of the ACR Manual on Contrast Media replaces all earlier editions. It is being published as a web- based document only so it can be updated as frequently as needed.