Basic Approach to Evaluating a Head Ct

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selection of Treatment for Large Non-Traumatic Subdural Hematoma Developed During Hemodialysis

Korean J Crit Care Med 2014 May 29(2):114-118 / http://dx.doi.org/10.4266/kjccm.2014.29.2.114 ■ Case Report ■ pISSN: 1229-4802ㆍeISSN: 2234-3261 Selection of Treatment for Large Non-Traumatic Subdural Hematoma Developed during Hemodialysis Chul-Hee Lee, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Neurosurgery, Gyeongsang National University School of Medicine, Jinju, Korea A 49-year-old man with end-stage renal disease was admitted to the hospital with a severe headache and vomiting. On neurological examination the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 15 and his brain CT showed acute subdural hematoma over the right cerebral convexity with approximately 11-mm thickness and 9-mm midline shift. We chose a conservative treatment of scheduled neurological examination, anticonvulsant medication, serial brain CT scanning, and scheduled hemodialysis (three times per week) without using heparin. Ten days after admission, he complained of severe headache and a brain CT showed an increased amount of hemorrhage and midline shift. Emergency burr hole trephination and removal of the hematoma were performed, after which symptoms improved. However, nine days after the operation a sudden onset of general tonic-clonic seizure developed and a brain CT demonstrated an in- creased amount of subdural hematoma. Under the impression of persistent increased intracranial pressure, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) in order to control intracranial pressure. Management at the ICU consisted of regular intravenous mannitol infusion assisted with continuous renal replacement therapy. He stayed in the ICU for four days. Twenty days after the operation he was discharged without specific neurological deficits. -

Article-P227.Pdf

CLINICAL ARTICLE J Neurosurg Pediatr 23:227–235, 2019 North American survey on the post-neuroimaging management of children with mild head injuries Jacob K. Greenberg, MD, MSCI,1 Donna B. Jeffe, PhD,2 Christopher R. Carpenter, MD, MSc,3 Yan Yan, MD, PhD,4 Jose A. Pineda, MD,5,6 Angela Lumba-Brown, MD,7 Martin S. Keller, MD,4 Daniel Berger, BA,1 Robert J. Bollo, MD, MS,8 Vijay M. Ravindra, MD, MSPH,8 Robert P. Naftel, MD,9 Michael C. Dewan, MD, MSCI,9 Manish N. Shah, MD,10 Erin C. Burns, MD,11 Brent R. O’Neill, MD,12 Todd C. Hankinson, MD,12 William E. Whitehead, MD, MPH,13 P. David Adelson, MD,14 Mandeep S. Tamber, MD, PhD,15 Patrick J. McDonald, MD, MHSc,16 Edward S. Ahn, MD,17 William Titsworth, MD,17 Alina N. West, MD, PhD,18 Ross C. Brownson, PhD,4,19,20 and David D. Limbrick Jr., MD, PhD1 Departments of 1Neurological Surgery, 2Medicine, 4Surgery, 5Pediatrics, and 6Neurology, 3Division of Emergency Medicine, 19Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center, and 20Prevention Research Center, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri; 7Department of Emergency Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, California; 8Department of Neurosurgery, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah; 9Department of Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee; 10Department of Neurosurgery, McGovern Medical School at University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas; 11Department of Pediatrics, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon; 12Department of Neurosurgery, -

ACR Manual on Contrast Media

ACR Manual On Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media Preface 2 ACR Manual on Contrast Media 2021 ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media © Copyright 2021 American College of Radiology ISBN: 978-1-55903-012-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Topic Page 1. Preface 1 2. Version History 2 3. Introduction 4 4. Patient Selection and Preparation Strategies Before Contrast 5 Medium Administration 5. Fasting Prior to Intravascular Contrast Media Administration 14 6. Safe Injection of Contrast Media 15 7. Extravasation of Contrast Media 18 8. Allergic-Like And Physiologic Reactions to Intravascular 22 Iodinated Contrast Media 9. Contrast Media Warming 29 10. Contrast-Associated Acute Kidney Injury and Contrast 33 Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Adults 11. Metformin 45 12. Contrast Media in Children 48 13. Gastrointestinal (GI) Contrast Media in Adults: Indications and 57 Guidelines 14. ACR–ASNR Position Statement On the Use of Gadolinium 78 Contrast Agents 15. Adverse Reactions To Gadolinium-Based Contrast Media 79 16. Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) 83 17. Ultrasound Contrast Media 92 18. Treatment of Contrast Reactions 95 19. Administration of Contrast Media to Pregnant or Potentially 97 Pregnant Patients 20. Administration of Contrast Media to Women Who are Breast- 101 Feeding Table 1 – Categories Of Acute Reactions 103 Table 2 – Treatment Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 105 Children Table 3 – Management Of Acute Reactions To Contrast Media In 114 Adults Table 4 – Equipment For Contrast Reaction Kits In Radiology 122 Appendix A – Contrast Media Specifications 124 PREFACE This edition of the ACR Manual on Contrast Media replaces all earlier editions. -

"Fullness" of the Pancreas on CT. Usually Benign, but EUS Plus/Minus FNA Is Warranted to Identify Malignancy

JOP. J Pancreas (Online) 2009 Jan 8; 10(1):37-42. ORIGINAL ARTICLE Focal or Diffuse "Fullness" of the Pancreas on CT. Usually Benign, but EUS Plus/Minus FNA Is Warranted to Identify Malignancy John David Horwhat1, Henning Gerke2, Ruben Daniel Acosta1, Darren A Pavey3, Paul S Jowell3 1Gastroenterology Service, Department of Medicine, Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Washington, DC, USA. 2Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Iowa City, IA, USA. 3Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Duke University Health System. Durham, NC, USA ABSTRACT Context The role of EUS to evaluate subtle radiographic abnormalities of the pancreas is not well defined. Objective To assess the yield of EUS±FNA for focal or diffuse pancreatic enlargement/fullness seen on abdominal CT scan in the absence of discrete mass lesions. Design Retrospective database review. Setting Tertiary referral center. Patients and interventions Six hundred and 91 pancreatic EUS exams were reviewed. Sixty-nine met inclusion criteria of having been performed for focal enlargement or fullness of the pancreas. Known chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic calcifications, acute pancreatitis, discrete mass on imaging, pancreatic duct dilation (greater than 4 mm) and obstructive jaundice were excluded. Main outcome measurement Rate of malignancy found by EUS±FNA. Results FNA was performed in 19/69 (27.5%) with 4 new diagnoses of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, one metastatic renal cell carcinoma, one metastatic colon cancer, one chronic pancreatitis and 12 benign results. Eight patients had discrete mass lesions on EUS; two were cystic. All malignant diagnoses had a discrete solid mass on EUS. Conclusions Pancreatic enlargement/fullness is often a benign finding related to anatomic variation, but was related to malignancy in 8.7% of our patients (6/69). -

Outcome Prediction in Patients of Traumatic Brain Injury Based on Midline Shift on CT Scan of Brain

Published online: 2021-01-21 THIEME Original Article 1 Outcome Prediction in Patients of Traumatic Brain Injury Based on Midline Shift on CT Scan of Brain Shrikant Govindrao Palekar1 Manish Jaiswal2, Mandar Patil3 Vijay Malpathak1 1Department of General Surgery, Dr. Vasantrao Pawar Medical Address for correspondence Manish Jaiswal, MCh, Department of College, Hospital & research center, Adgaon, Nasik, India Neurosurgery, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, 2Department of Neurosurgery, King George’s Medical University, Uttar Pradesh, 226003, India Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India (e-mail: [email protected]). 3Department of Neurosurgery, Tirunelveli Government Medical College, Tamil Nadu, India Indian J Neurosurg Abstract Background Clinicians treating patients with head injury often take decisions based on their assessment of prognosis. Assessment of prognosis could help communication with a patient and the family. One of the most widely used clinical tools for such pre- diction is the Glasgow coma scale (GCS); however, the tool has a limitation with regard to its use in patients who are under sedation, are intubated, or under the influence of alcohol or psychoactive drugs. CT scan findings such as status of basal cistern, mid- line shift, associated traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), and intraventricular hemorrhage are useful indicators in predicting outcome and also considered as valid options for prognostication of the patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI), especially in emergency setting. Materials and Methods 108 patients of head injury were assessed at admission with clinical examination, history, and CT scan of brain. CT findings were classified accord- ing to type of lesion and midline shift correlated to GCS score at admission. -

Coronary Artery Calcium Quantification in Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography Angiography

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Computer Science Dissertations Department of Computer Science 12-18-2013 Coronary Artery Calcium Quantification in Contrast-enhanced Computed Tomography Angiography Abinashi Dhungel Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cs_diss Recommended Citation Dhungel, Abinashi, "Coronary Artery Calcium Quantification in Contrast-enhanced Computed Tomography Angiography." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cs_diss/80 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Computer Science at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Computer Science Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORONARY ARTERY CALCIUM QUANTIFICATION IN CONTRAST-ENHANCED COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY ANGIOGRAPHY by ABINASHI DHUNGEL Under the Direction of Dr. Michael Weeks ABSTRACT Coronary arteries are the blood vessels supplying oxygen-rich blood to the heart muscles. Coronary artery calcium (CAC), which is the total amount of calcium deposited in these arteries, indicates the presence or the future risk of coronary artery diseases. Quantification of CAC is done by using computed tomography (CT) scan which uses attenuation of x- ray by different tissues in the body to generate three-dimensional images. Calcium can be easily spotted in the CT images because of its higher opacity to x-ray compared to that of the surrounding tissue. However, the arteries cannot be identified easily in the CT images. Therefore, a second scan is done after injecting a patient with an x-ray opaque dye known as contrast material which makes different chambers of the heart and the coronary arteries visible in the CT scan. -

Neuroimaging Radiological Interpretation System for Acute Traumatic Brain Injury

JOURNAL OF NEUROTRAUMA 35:2665–2672 (November 15, 2018) ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2017.5311 Neuroimaging Radiological Interpretation System for Acute Traumatic Brain Injury Max Wintermark,1,* Ying Li,1,* Victoria Y. Ding,2,* Yingding Xu,1 Bin Jiang,1 Robyn L. Ball,2 Michael Zeineh,1,* Alisa Gean,3 and Pina Sanelli4 Abstract The purpose of the study was to develop an outcome-based NeuroImaging Radiological Interpretation System (NIRIS) for patients with acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) that would standardize the interpretation of noncontrast head computer tomography (CT) scans and consolidate imaging findings into ordinal severity categories that would inform specific patient management actions and that could be used as a clinical decision support tool. We retrospectively identified all patients transported to our emergency department by ambulance or helicopter for whom a trauma alert was triggered per established criteria and who underwent a noncontrast head CT because of suspicion of TBI, between November 2015 and April 2016. Two neuroradiologists reviewed the noncontrast head CTs and assessed the TBI imaging common data elements (CDEs), as defined by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Using descriptive statistics and receiver operating characteristic curve analyses to identify imaging characteristics and associated thresholds that best distinguished among outcomes, we classified patients into five mutually exclusive categories: 0-discharge from the emergency department; 1- follow-up brain imaging and/or admission; 2-admission to an advanced care unit; 3-neurosurgical procedure; 4-death up to 6 months after TBI. Sensitivity of NIRIS with respect to each patient’s true outcome was then evaluated and compared with that of the Marshall and Rotterdam scoring systems for TBI. -

Quickbrain MRI for the Detection of Acute Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury

CLINICAL ARTICLE J Neurosurg Pediatr 19:259–264, 2017 QuickBrain MRI for the detection of acute pediatric traumatic brain injury David C. Sheridan, MD, MCR,1 Craig D. Newgard, MD, MPH,1 Nathan R. Selden, MD, PhD,2 Mubeen A. Jafri, MD,3 and Matthew L. Hansen, MD, MCR1 1Department of Emergency Medicine, Center for Policy and Research in Emergency Medicine, 2Department of Neurological Surgery, Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, and 3Department of Surgery, Division of Pediatric Surgery, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon OBJECTIVE The current gold-standard imaging modality for pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) is CT, but it confers risks associated with ionizing radiation. QuickBrain MRI (qbMRI) is a rapid brain MRI protocol that has been studied in the setting of hydrocephalus, but its ability to detect traumatic injuries is unknown. METHODS The authors performed a retrospective cohort study of pediatric patients with TBI who were undergoing evaluation at a single Level I trauma center between February 2010 and December 2013. Patients who underwent CT imaging of the head and qbMRI during their acute hospitalization were included. Images were reviewed independently by 2 neuroradiology fellows blinded to patient identifiers. Image review consisted of identifying traumatic mass lesions and their intracranial compartment and the presence or absence of midline shift. CT imaging was used as the reference against which qbMRI was measured. RESULTS A total of 54 patients met the inclusion criteria; the median patient age was 3.24 years, 65% were male, and 74% were noted to have a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 14 or greater. The sensitivity and specificity of qbMRI to detect any lesion were 85% (95% CI 73%–93%) and 100% (95% CI 61%–100%), respectively; the sensitivity increased to 100% (95% CI 89%–100%) for clinically important TBIs as previously defined. -

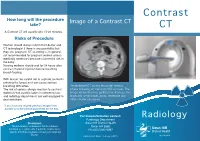

Contrast CT Take? CT a Contrast CT Will Usually Take 15-20 Minutes

Contrast How long will the procedure Image of a Contrast CT take? CT A Contrast CT will usually take 15-20 minutes. Risks of Procedure Women should always inform their doctor and CT technologist if there is any possibility that they are pregnant. CT scanning is, in general, not recommended for pregnant women unless medically necessary because of potential risk to the baby. Nursing mothers should wait for 24 hours after contrast material injection before resuming breast-feeding. With Ioscan, be careful not to aspirate (contents entering the lungs) as it can cause serious breathing difficulties. An abdomen CT during the portal-venous The risk of serious allergic reaction to contrast phase following an injection of IV contrast. The materials that contain iodine is extremely low, image shows the liver, gallbladder, kidneys, the and radiology departments are well-equipped to large and small bowel, aorta, vertebrae and deal with them. other smaller structures. If you have any related previous images from another provider please bring them on the day. For more information contact: Radiology Radiology Department Disclaimer: Swan Hill District Health The information contained in this brochure is Swan Hill 3585 intended as a guide only. If patients require more Ph: (03) 5033 9287 specific information please contact your referring Doctor. Publication Date: February 2013 What is a Contrast CT? Preparation CT scans of internal organs, bones, soft tissue Women must inform the radiographer if there is If you are over 55 years of age, your doctor will and blood vessels reveal more details than any chance that they are pregnant or if they are give you a pathology slip to have a ‘U & E’ blood regular x-rays. -

Development and Validation of Deep Learning Algorithms for Detection of Critical Findings in Head CT Scans

Development and Validation of Deep Learning Algorithms for Detection of Critical Findings in Head CT Scans Sasank Chilamkurthy1, Rohit Ghosh1, Swetha Tanamala1, Mustafa Biviji2, Norbert G. Campeau3, Vasantha Kumar Venugopal4, Vidur Mahajan4, Pooja Rao1, and Prashant Warier1 1Qure.ai, Mumbai, IN 2CT & MRI Center, Nagpur, IN 3Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 4Centre for Advanced Research in Imaging, Neurosciences and Genomics, New Delhi, IN Abstract Importance Non-contrast head CT scan is the current standard for initial imaging of patients with head trauma or stroke symptoms. Objective To develop and validate a set of deep learning algorithms for automated detec- tion of following key findings from non-contrast head CT scans: intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and its types, intraparenchymal (IPH), intraventricular (IVH), subdural (SDH), ex- tradural (EDH) and subarachnoid (SAH) hemorrhages, calvarial fractures, midline shift and mass effect. Design and Settings We retrospectively collected a dataset containing 313,318 head CT scans along with their clinical reports from various centers. A part of this dataset (Qure25k dataset) was used to validate and the rest to develop algorithms. Additionally, a dataset (CQ500 dataset) was collected from different centers in two batches B1 & B2 to clinically validate the algorithms. Main Outcomes and Measures Original clinical radiology report and consensus of three independent radiologists were considered as gold standard for Qure25k and CQ500 datasets respectively. Area under receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) for each finding was primarily used to evaluate the algorithms. Results Qure25k dataset contained 21,095 scans (mean age 43:31; 42:87% female) while batches B1 and B2 of CQ500 dataset consisted of 214 (mean age 43:40; 43:92% female) and 277 (mean age 51:70; 30:31% female) scans respectively. -

Guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media Part 1

Guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media Part 1 This part 1 comprises: 1. Prevention of post-contrast acute kidney injury 2. Use of iodine-containing contrast media in patients with diabetes type 2 who use metformin 3. Use of iodine-containing contrast media in patients undergoing dialysis INITIATED BY Radiological Society of the Netherlands IN ASSOCIATION WITH Netherlands Association of Internal Medicine Dutch Federation for Nephrology Dutch Society of Intensive Care Association of Surgeons of the Netherlands The Netherlands Society of Cardiology Dutch Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians Dutch Association of Urology Dutch Society Medical Imaging and Radiotherapy WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists FINANCED BY Quality Funds of Medical Specialists 1 Guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media – Part 1 Colophon GUIDELINE SAFE USE OF CONTRAST MEDIA – PART 1 ©2017 Radiological Society of the Netherlands Address: Taalstraat 40, 5260 CB Vught 0800 0231 536 / 073 614 1478 [email protected] www.radiologen.nl All rights reserved. The text in this publication can be copied, saved or made public in any manner: electronically, by photocopy or in another way, but only with prior permission of the publisher. Permission for usage of (parts of) the text can be requested by writing or e- mail, only form the publisher. Address and email: see above. 2 Guideline Safe Use of Contrast Media – Part 1 Index Working group ........................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1 General Introductions ............................................................................. 5 Chapter 2 Justification of this Guideline ................................................................. 10 Chapter 3 PC-AKI: Definitions, Terminology & Clinical Course.….…………….…………… 19 Chapter 4 Risk Stratification and Risk Stratification Tools ...................................... -

Saddle Pulmonary Embolism on Non-Contrast CT

Journal of Lung, Pulmonary & Respiratory Research Case Report Open Access Saddle pulmonary embolism on non-contrast CT Abstract Volume 8 Issue 2 - 2021 Background: A saddle pulmonary embolism (PE) is a large embolism that straddles the Bilal Chaudhry MD,1 Kirill Alekseyev MD, bifurcation of the pulmonary trunk. This PE extends into the right and left pulmonary MBA,2 Lidiya Didenko MS4,2 Gennadiy Ryklin arteries. There is a greater incidence in males. Common features of a PE include dyspnea, 1 1 tachypnea, cough, hemoptysis, pleuritic chest pain, tachycardia, hypotension, jugular DO, David Lee MD 1 venous distension, and severe cases Kussmaul sign. The Wells criteria for PE is used as Christiana Care Health System, USA 2Post-Acute Medical Rehabilitation Hospital of Dover, American the pretest probability. Diagnostics include D-dimer levels, CT pulmonary angiography University of Antigua, USA (CTPA), ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan), echocardiography, lower extremity venous ultrasound, chest x-ray, pulmonary angiography, and electrocardiography (ECG). Correspondence: Lidiya Didenko MS4, Post-Acute Medical Case description: We present a 65-year-old male that presented with a two-week history Rehabilitation Hospital of Dover, American University of Antigua, of dyspnea with non-radiating intermittent chest pressure. Initial V/Q scan showed a low 1240 McKee Road, Dover, DE 19904, USA, Tel (862)377-1907, Email probability for PE, but a subsequent non-contrast CT revealed that he indeed had a saddle PE. Received: May 10, 2021 | Published: May 28, 2021 Keywords: pulmonary embolism, v/q scan, CT, cor pulmonale, COPD, obstructive sleep apnea Abbreviations: PE, pulmonary embolism; V/Q scan, intermittent chest pressure in the retrosternal area without radiation.