The Palaeolithic Exploitation of the Lithic Raw Materials and the Organization of Foraging Territory in Northeastern Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PREHISTORIC STONE ARTEFACT ANALYSIS MA MODULE (15 Credits): ARCL0101 MODULE HANDBOOK 2019-20

INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY PREHISTORIC STONE ARTEFACT ANALYSIS MA MODULE (15 credits): ARCL0101 MODULE HANDBOOK 2019-20 Tuesday 9 am – 11 pm, Term 2 Room 410 and Lithics Lab, Institute of Archaeology Deadlines for coursework for this module: 1st report: 27th April 2020 2nd report: 12th June 2020 Target dates for return of marked coursework to students: 1st report: 18th May 2020 2nd report: 10th July 2020 Co-ordinator: Dr Tomos Proffitt Email: [email protected] Room 206 Please see the last page of this document for important information about submission and marking procedures 1 OVERVIEW Short description This series of lectures, practical work and discussion provides an introduction to basic and advanced analytical techniques and addresses some of the methodological and interpretative approaches used in the study of lithic assemblages. It is twofold in its approach: 1) it addresses technologies characteristic of the Old Stone Age/Palaeolithic and Neolithic periods; 2) it considers ways that lithic artefacts and lithic analysis can contribute towards an understanding of past human cognition, behaviour and the interpretation of human material culture. There is an emphasis on practical handling and study as this is the best way to learn about struck stone artefacts. Module schedule Lecture (all lectures in Practical (most practicals in Lecturer Date Room 410) Room 410 or Lithics Lab) Week 1 Approaches to lithic analysis Labelling and curation, raw material T. Proffitt 14-Jan identification (Lithics Lab) Week 2 Origins of stone tool technology Artefact categories, core and flake T. Proffitt 21-Jan attributes (Room 410) Week 3 Stone tool experimental Experimental knapping T. -

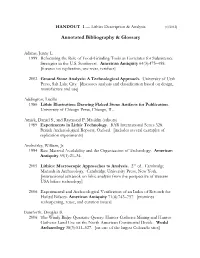

Lithic Analysis Bibliography & Glossary

HANDOUT 1 — Lithics Description & Analysis [4/2012] Annotated Bibliography & Glossary Adams, Jenny L. 1999 Refocusing the Role of Food-Grinding Tools as Correlates for Subsistence Strategies in the U.S. Southwest. American Antiquity 64(3):475–498. [focuses on replication, use wear, residues] 2002 Ground Stone Analysis: A Technological Approach. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City. [discusses analysis and classification based on design, manufacture and use] Addington, Lucille 1986 Lithic Illustration: Drawing Flaked Stone Artifacts for Publication. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL. Amick, Daniel S., and Raymond P. Mauldin (editors) 1989 Experiments in Lithic Technology. BAR International Series 528. British Archaeological Reports, Oxford. [includes several examples of replication experiments] Andrefsky, William, Jr. 1994 Raw-Material Availability and the Organization of Technology. American Antiquity 59(1):21–34. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis. 2nd ed. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, New York. [instructional textbook on lithic analysis from the perspective of western USA biface technology] 2006 Experimental and Archaeological Verification of an Index of Retouch for Hafted Bifaces. American Antiquity 71(4):743–757. [examines resharpening, reuse, and curation issues] Bamforth, Douglas B. 2006 The Windy Ridge Quartzite Quarry: Hunter-Gatherer Mining and Hunter- Gatherer Land Use on the North American Continental Divide. World Archaeology 38(3):511–527. [on one of the largest Colorado sites] Barnett, Franklin 1991 Dictionary of Prehistoric Indian Artifacts of the American Southwest. Northland Publishing Co., Flagstaff, AZ. Barton, C. Michael 1996 Beyond the Graver: Reconsidering Burin Function. Journal of Field Archaeology 23(1):111–125. [well-illustrated, but specific topic] Benedict, James B. -

Managing Lithic Scatters and Sites Archaeological Guidance for Planning Authorities and Developers

Managing Lithic Scatters and Sites Archaeological guidance for planning authorities and developers 0 Managing Lithic Scatters and Sites: Archaeological guidance for planning authorities and developers Summary Lithic scatters and sites are an important archaeological resource that can provide valuable insights into prehistory. Most commonly found as scatters of worked stone, usually suspended in modern ploughsoil deposits, which have been disturbed from their original archaeological context through ploughing. Undisturbed lithic sites can also be found through further evaluation and excavations, where lithics have been sealed by cover deposits or preserved in sub-surface features/horizons. Lithic scatters can represent a palimpsest of activity, sometimes containing several technologies from different archaeological periods. Consequently, the value of lithic scatters as a source for investigating past behaviour has often been undervalued. However, in many cases, especially for sites dating from the Palaeolithic period through to the Bronze Age, lithic scatters are likely to represent the only available archaeological evidence of past human activity and subsistence strategies. By studying and understanding their formation, spatial distribution and technological attributes, we can get closer to understanding the activities of the people who created these artefacts. Lithic scatters are often perceived as being particularly problematic from a heritage resource and development management perspective, because the standard archaeological methodologies presently employed are often not sufficiently subtle to ensure their effective identification and characterisation (Last 2009). This can either lead to an unquantified loss of important archaeological evidence, or the under-estimation of the magnitude of a site’s scale and importance, leading to missed research opportunities or, in a planning/development context, potentially avoidable expense, delay and inconvenience. -

Quartzite and Vein Quartz As Lithic Raw Materials Reconsidered: a View from the Korean Paleolithic

Quartzite and Vein Quartz as Lithic Raw Materials Reconsidered: A View from the Korean Paleolithic CHUNTAEK SEONG SINCE THE EXCA V AnON OF SOKCHANG-RI (Sohn 1968, 1970, 1993) in south ern Korea by local scholars in the 1960s,1 the last few decades witnessed a signifi cant increase in the number of discovered and excavated Paleolithic sites. From the late 1970s, Chongokni (Jeongok-ri), known for its "Acheulian-like" hand axes, and neighboring sites along the Imjin-Hantan River have been excavated extensively (NICP 1999; Yi and Clark 1983; Fig. 1, also see Fig. 3). A series of salvage archaeological expeditions and both occasional and systematic site surveys have revealed a dense distribution of Paleolithic locations in regions such as the Imjin-Hantan River and Boseong River valleys. The number of archaeological locations including surface scatters yielding Paleolithic chipped stone artifacts well exceeds 500 in the southern Korean Peninsula (Choi B. et al. 2001; Lee G. 1999, 2001; KPM 2001; Yi 2001). The majority of Korean Paleolithic materials are quartzite and vein quartz arti facts. The raw materials often account for 90 percent of the total artifact collec tion in earlier assemblages, while the usage of the materials decreases in later industries. As J. D. Clark (1983: 595) pointed out, it is believed that "informality is the keynote" of the industry as represented by the collection from Chongokni. Because of this notion, the trend of uncritically accepting many European Paleo lithic artifact types has been questioned, because European typology is too specific to apply to Korean Paleolithic artifacts (Bae 1988; NICP 1999; Yi 1989).2 Given this supposed informality, it is not desirable to examine the industry based on an established classification focusing on general morphology. -

49. Lithic Assemblages

Lithic Assemblages A guide to processing, analysis and interpretation Guide 49 BAJR Series © Torben Bjarke Ballin 2017 Processing, analysis and interpretation of lithic assemblages: BAJR Guide 49 ‘How to squeeze blood from stones’ – processing, analysis and interpretation of lithic assemblages Torben Bjarke Ballin LITHIC RESEARCH, Stirlingshire Honorary Research Fellow, University of Bradford FOREWORD In March 2017, the Scottish Archaeological Research Framework (ScARF) organised a lithics workshop in Edinburgh, aiming at teaching anybody with an interest in lithics the basic elements of this specialist field. The author was one of several speakers, and he gave a ‘hands-on’ presentation of the main types of lithic debitage, cores and tools people interested in archaeology may encounter. Following this event, BAJR contacted the author, and it was agreed to transform the author’s presentation into a BAJR guide for British lithics, in collaboration with ScARF. The guide should be perceived as a brief introduction to lithics and ‘how to squeeze blood from stones’ – that is, how to interpret the past through the lithic evidence. If the reader needs more detail or information, he/she should consult more specialized archaeological literature. The guide deals with the processing of lithic finds from the Late Upper Palaeolithic to the Early Iron Age, but not the Lower, Middle, and Early Upper Palaeolithic periods. over image: Morar Quartz Industry, Wellcome Images,(used under creative commons licence) 1 | P a g e Processing, analysis and interpretation -

Using Spatial Context to Identify Lithic Selection Behaviors T Amy E

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 24 (2019) 1014–1022 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Using spatial context to identify lithic selection behaviors T Amy E. Clark Department of Anthropology, University of Oklahoma, 455 West Lindsey, Norman, OK 73019, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: To differentiate between “tools” and “debris”, lithic analysts usually rely on the presence or absence of retouch, Lithic technology traces of use-wear, or extrapolation of the “desired end products” through the reconstruction of the chaîne Spatial analysis opératoire. These methods usually fail to identify the full range of unretouched lithics utilized, especially at the Middle Paleolithic assemblage scale. The spatial context of lithic pieces is often overlooked as an additional tool to identify tool selection. This paper presents the results of a study of seven open-air Middle Paleolithic sites in France, where lithic production and selection can be segregated in space. Two interrelated methods are utilized, one which relies on refitting data and the other which focuses on the differential spatial distribution of lithic artifacts. At these sites, the selected lithics identified using these methods match up well with what archaeologists have long thought to be “desired end products” but many of these sought pieces were also left with the manufacturing debris, indicating that lithics were produced in mass irrespective of immediate demand. The methods presented in this paper can therefore provide answers to many salient questions regarding lithic production and selection and are applicable to any context where lithic production has a strong spatial signature. -

Do the Lithic Assemblages at the Middle-Upper Paleolithic Boundary Support the Strict Replacement Hypothesis for Modern Human Origins?

Indiana M. Jones Department of Anthropology Arizona State University Stones and Bones: Do the Lithic Assemblages at the Middle-Upper Paleolithic Boundary Support the Strict Replacement Hypothesis for Modern Human Origins? In 1829-30, P.C. Schmerling discovered the fragmentary remains of a child's skull In Engis Cave near Liege, Belgium. These fragments were the first Neanderthal remains to be found. This being the pre-Darwinian period and because they exhibited non-modern morphologies, the scientific community showed very little, if any, interest In the find. In 1848, a partial skull from an adult Neanderthal was discovered In a cave located at Forbes Quarry on the Rock of Gibraltar. Like the Belgium skull fragments, the Forbes Quarry skull received scant attention (Klein 1989). It was not until 1856, when workers quarrying in the Feldhofer Cave in the Neander Valley near Dusseldorf, Germany, unearthed the skeletal remains of what appeared to a human skullcap and several postcranial bones, that people began speculating as to their origins and significance of these odd, non-modern, bones (Klein 1989, Wolpoff 1980). Since these initial finds in northern Europe, many Neanderthal remains have been found across Europe, as far west as Great Britain and the Iberian peninsula, eastward into western Asia. Remains have been discovered In Russia and former Soviet Union provinces, the former Yugoslavian Republic, France, Spain, Italy, Iraq and Israel (Wolpoff 1980, Tattersall, et al. 1988). The dating of the finds have the Neanderthals occupying Europe and the Near East/Western Asia from ~100,000 to 35,000 years ago, during the late Pleistocene. -

Prehistoric Stone Artefact Analysis Module Handbook 2018-19

INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY MA MODULE (15 credits): ARCL0101 PREHISTORIC STONE ARTEFACT ANALYSIS MODULE HANDBOOK 2018-19 WEDNESDAY 11 am – 2 pm, Term 1 Room 410 and Lithics Lab, Institute of Archaeology Turnitin Class ID: 3884599 Turnitin password: IoA1819 Deadlines for coursework for this module: 1st report: 5th December 2nd report: 31st January Target dates for return of marked coursework to students: 1st report: 7th January 2nd report: 28th February Co-ordinator: Prof Ignacio de la Torre Email: [email protected] Room 204B Telephone: 020-7679-4721 Please see the last page of this document for important information about submission and marking procedures 1 OVERVIEW Short description This series of lectures, practical work and discussion provides an introduction to basic and advanced analytical techniques and addresses some of the methodological and interpretative approaches used in the study of lithic assemblages. It is twofold in its approach: 1) it addresses technologies characteristic of the Old Stone Age/Palaeolithic and Neolithic periods; 2) it considers ways that lithic artefacts and lithic analysis can contribute towards an understanding of past human cognition, behaviour and the interpretation of human material culture. There is an emphasis on practical handling and study as this is the best way to learn about struck stone artefacts. Module schedule Lecture (all lectures in Practical (most practicals in Lecturer Date Room 410) Room 410 or Lithics Lab) Week 1 Approaches to lithic analysis Labelling and curation, raw material I. de la Torre 03-Oct identification (Lithics Lab) Week 2 Origins of stone tool technology Artefact categories, core and flake I. -

Lithic Analysis Spring 2014

Rutgers University Lithic Analysis Spring 2014 Course Syllabus 070-391 Lithic Analysis Class hours: Thursday 2:15-5:15 PM Classroom: Biological Sciences, 302 Instructor: Zeljko Rezek [email protected] Office: Biological Sciences, Suite 208 Office hours: Mon 1-5pm, Tue 10-12pm, Wed 10-11am & 12.30-1.30pm, Thu 12.30- 1.30pm, or by appointment Course description This course will examine the potential of stone tools and archaeological lithic record for the study of technological, economic and social aspects of hominin behavior in the past. It will integrate and evaluate a range of theoretical perspectives and analytical methods that have been employed in archaeological interpretation of knapped and ground lithic artifacts from various temporal and geographic contexts. Some of the topics to be covered in this course are methods of lithic analysis and their limitations, the effects of physical properties of raw material on the production and maintenance of lithic artifacts, a re-examination of the link between observed technological complexity of lithic artifacts and complexity in behavior, etc. Pre/Co-requisites Students are expected either to have taken already, or are taking during the same term, an introductory course in archaeology (070-105). Alternatively, they can ask for the permission to enroll from the instructor. Required readings Required readings comprise one textbook and a series of published papers. The required text is: William Andrefsky 2006. Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Analysis Cambridge University Press (Available in the Campus Bookstore, as well as on online sources. The older edition can be used too.) Published papers, essential and additional, will be posted on Sakai, https://sakai.rutgers.edu, at least 7 days before their reading due date. -

Identification of Activity Areas Through Lithic Analysis - the Longhorn Site (41KT53) in the Upper Brazos River Basin, Kent County, Texas

Identification of Activity Areas Through Lithic Analysis - The Longhorn Site (41KT53) in the Upper Brazos River Basin, Kent County, Texas by Kathryn Mira Smith, B.S. A Thesis In Anthropology Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Accepted Dr. Brett Houk Co-Chair Dr. Eileen Johnson Co-Chair Dr. Tamra Walter Ralph Ferguson Dean of the Graduate School December 2010 © 2010 Kathryn Mira Smith Texas Tech University, Kathryn Smith, December 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee members for their advice and assistance throughout this project: Dr. Brett A. Houk, chair; Dr. Eileen G. Johnson, co-chair; and Dr. Tamra L. Walter, member. Additional thanks goes to the Museum of Texas Tech University and Lubbock Lake Landmark for access to their collections and equipment, as well as the encouragement and support of their staff. Furthermore, special thanks go to the following individuals for their contributions to this research: Douglas K. Boyd, site information; Dr. Bernard A. Schriever, photography; Dr. Stance Hurst, lithic expertise; Dr. Kevin Mulligan, ArcGIS support; Cynthia Lopez, archival research; Richard Beres and Samuel Thompson, database support. Finally, I wish to acknowledge the never-ending support of my family and friends. ii Texas Tech University, Kathryn Smith, December 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT vi LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF FIGURES viii I INTRODUCTION 1 Archaeological Background 1 Project Area Investigations 3 Research Orientation 5 Excavations at 41KT53 7 Results and Interpretations 9 Cultural Background 11 Paleoindian (11,500 RCYBP to 8,500 RCYBP) 11 Archaic (8,500 RCYBP to 2,000 RCYBP) 13 Ceramic (2,000 RCYBP to A.D. -

An Introduction to Stone Artifact Analysis

Chris Clarkson and Sue O’Connor 6 An Introduction to Stone Artifact Analysis Introduction Lithic analysis is a fundamental and often key component of contemporary archaeological practice of relevance to any region or time period where stone tools were employed in past technologies. For this reason, acquiring familiarity with the identification and analysis of stone artifacts is an important compo- nent of archaeological training and can be an important professional skill. Needless to say, there are numerous approaches to analyzing stone artifacts tailored to the vast range of topics being researched, and the one presented in this chapter may differ from those in use in some parts of the world or for particular time periods or assemblage types. Rather than review the huge diver- sity of approaches to lithic analysis, this chapter aims to arm the student of lithic technology with a set of principles to guide the construction of their research design, alert them to the philosophical underpinnings of various kinds of stone analysis, point to some simple but frequently overlooked issues of data management, provide an overview of some common laboratory techniques and analyses, and provide case studies and suggested readings that offer insight into both the process of actually doing stone analysis as well as drawing mean- ingful conclusions from the results. It takes a question-and-answer format in the hope that some frequently asked questions might be addressed in a straight- forward manner. There are many good reasons why archaeologists study stone artifacts. Primary An overview among them is the fact that stone artifacts are typically the most abundant and durable traces of past human activity of any of the artifactual remains archae- Why study stone ologists have available to study. -

The Lithic Technology of a Late Woodland

THE LITHIC TECHNOLOGY OF A LATE WOODLAND OCCUPATION ON THE DELAWARE BAY: KIMBLE’S BEACH SITE (28CM36A), CAPE MAY COUNTY, NEW JERSEY by JAMES P. KOTCHO A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Anthropology Written under the direction of Craig S. Feibel and approved by ______________________ ______________________ ______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January, 2009 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Lithic Technology of a Late Woodland Occupation on the Delaware Bay: Kimble’s Beach Site (28CM36A), Cape May County, New Jersey by JAMES P KOTCHO Thesis Director: Craig S. Feibel This study aims to identify technological practices of Native American people who lived at the Kimble’s Beach site (28CM36A) during the Late Woodland period (ca. 800/900-1650 AD) of Eastern prehistory. This site is located in the northern portion of the Cape May Peninsula along the margin of the Delaware Bay in New Jersey. It was jointly excavated by Rutgers University and Stockton State College in the period 1995- 1998. The study is limited to the excavations at the Beach Face locus, which is the modern beach face. The site was in an upland location 400-500 m from the bay during the Late Woodland period. Data collected from chipped stone debitage recovered from the beach face are compared with data collected from the debitage derived from experimentally replicated small triangular projectile points and several types of scrapers found in the assemblage to identify tool making behavior represented at the site.