Christian Identity in Israel Dissertation Presented In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Practices of Irrigation Water Pricing

\J4S ILI(QQ POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1460 Public Disclosure Authorized Efficiency and Equity Pricing of water may affect allocation considerations by Considerations in Pricing users. Efficiency isattainable andAllocating Irrigation wheneverthe pricing method affectsthe demandfor Public Disclosure Authorized Water irrigation water. The extent to which water pricing methods can affect income Yacov Tsur redistributionis limited.To Ariel Dinar affect incomeinequality, a water pricing method must include certain forms of water quantity restrictions. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The WorldBank Agricultureand Natural ResourcesDepartment Agricultural Policies Division May 1995 POLICYRESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1460 Summary findings Economic efficiency has to do with how much wealth a inefficient allocation. But they are usually easier to given resource base can generate. Equity has to do with implement and administer and require less information. how that wealth is to be distributed in society. Economic The extent to which water pricing methods can effect efficiency gets far more attention, in part because equity income redistribution is limited, the authors conclude. considerations involve value judgments that vary from Disparities in farm income are mainly the result of person to person. factors such as farm size and location and soil quality, Tsur and Dinar examine both the efficiency and the but not water (or other input) prices. Pricing schemes equity of different methods of pricing irrigation water. that do not involve quantity quotas cannot be used in After describing water pricing practices in a number of policies aimed at affecting income inequality. countries, they evaluate their efficiency and equity. The results somewhat support the view that water In general they find that water use is most efficient prices should not be used to effect income redistribution when pricing affects the demand for water. -

National Outline Plan NOP 37/H for Natural Gas Treatment Facilities

Lerman Architects and Town Planners, Ltd. 120 Yigal Alon Street, Tel Aviv 67443 Phone: 972-3-695-9093 Fax: 9792-3-696-0299 Ministry of Energy and Water Resources National Outline Plan NOP 37/H For Natural Gas Treatment Facilities Environmental Impact Survey Chapters 3 – 5 – Marine Environment June 2013 Ethos – Architecture, Planning and Environment Ltd. 5 Habanai St., Hod Hasharon 45319, Israel [email protected] Unofficial Translation __________________________________________________________________________________________________ National Outline Plan NOP 37/H – Marine Environment Impact Survey Chapters 3 – 5 1 Summary The National Outline Plan for Natural Gas Treatment Facilities – NOP 37/H – is a detailed national outline plan for planning facilities for treating natural gas from discoveries and transferring it to the transmission system. The plan relates to existing and future discoveries. In accordance with the preparation guidelines, the plan is enabling and flexible, including the possibility of using a variety of natural gas treatment methods, combining a range of mixes for offshore and onshore treatment, in view of the fact that the plan is being promoted as an outline plan to accommodate all future offshore gas discoveries, such that they will be able to supply gas to the transmission system. This policy has been promoted and adopted by the National Board, and is expressed in its decisions. The final decision with regard to the method of developing and treating the gas will be based on the developers' development approach, and in accordance with the decision of the governing institutions by means of the Gas Authority. In the framework of this policy, and in accordance with the decisions of the National Board, the survey relates to a number of sites that differ in character and nature, divided into three parts: 1. -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

The Absentee Property Law and Its Implementation in East Jerusalem a Legal Guide and Analysis

NORWEGIAN REFUGEE COUNCIL The Absentee Property Law and its Implementation in East Jerusalem A Legal Guide and Analysis May 2013 May 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Consulting legal advisor: Adv. Sami Ershied Language editor: Risa Zoll Hebrew-English translations: Al-Kilani Legal Translation, Training & Management Co. Cover photo: The Cliff Hotel, which was declared “absentee property”, and its owner Ali Ayad. (Photo by: Mohammad Haddad, 2013). This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non-governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Talia Sasson, Adv. Daniel Seidmann and Adv. Raphael Shilhav for their insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 8 2. Background on the Absentee Property Law .................................................. 9 3. Provisions of the Absentee Property Law .................................................... 14 3.1 Definitions .................................................................................................................... -

500 DUNAM on the MOON a Documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES 500 DUNAM on the MOON a Documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES

500 DUNAM ON THE MOON a documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES 500 DUNAM ON THE MOON a documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES SYNOPSIS 500 DUNAM ON THE M00N is a documentary about the Palestinian village of Ayn Hawd which was captured and depopulated by Israeli forces in the 1948 war and subsequently transformed into a Jewish artist's colony and renamed Ein Hod. It tells the story of the village's original inhabitants who, after expulsion, settled only 1.5 kilometers away in the outlying hills. Since Israeli law prevents Palestinian refugees from returning to their homes, the refugees of Ayn Hawd established a new village: “Ayn Hawd al-Jadida” (The New Ayn Hawd). Ayn Hawd al-Jadida is an unrecognized village, which means that it receives no services such as electricity, water, or an access road. Relations between the artists and the refugees are complex: unlike most Israelis, the residents of Ein Hod know the Palestinians who lived there before them, since the latter have worked as hired hands for the former. Unlike most Palestinian refugees, the residents of Ayn Hawd al-Jadida know the Israelis who now occupy their homes, the art they produce, and the peculiar ways they try to deal with the fact that their society was created upon the ruins of another. It echoes the story of indigenous peoples everywhere: oppression, resistance, and the struggle to negotiate the scars of the past with the needs of the present and the hopes for the future. Addressing the universal issues of colonization, landlessness, housing rights, gentrification, and cultural appropriation in the specific context of Israel/Palestine, 500 DUNAM ON THE M00N documents the art of dispossession and the creativity of the dispossessed. -

Religious Offerings and Sacrifices in the Ancient Near East

ARAMPeriodical religious offerings and sacrifices in the ancient near east astrology in the ancient near east the river jordan volume 29, 1&2 2017 LL Aram is a peer-reviewed periodical published by the ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies The Oriental Institute University of Oxford Pusey Lane OXFORD OX1 2LE - UK Tel. +44 (0)1865 51 40 41 email: [email protected] www.aramsociety.org 6HQLRU(GLWRU'U6KD¿T$ERX]D\G8QLYHUVLW\RI2[IRUG 6KD¿TDERX]D\G#RULQVWDFXN English and French editor: Prof. Richard Dumbrill University of London [email protected] Articles for publication to be sent to ARAM at the above address. New subscriptions to be sent to ARAM at the above address. Book orders: Order from the link: www.aramsociety.org Back issues can be downloaded from: www.aramsociety.org ISSN: 0959-4213 © 2017 ARAM SOCIETY FOR SYRO-MESOPOTAMIAN STUDIES All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. iii ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies Forty-Second International Conference religious offerings and sacrifices in the ancient near east The Oriental Institute Oxford University 20-23 July 2015 iv ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies Thirty-Ninth International Conference astrology in the ancient near east The Oriental Institute Oxford University 13-15 July 2015 v ARAM Society for Syro-Mesopotamian Studies Forty-First International Conference the river jordan The Oriental Institute Oxford University 13-15 July 2015 vi Table of Contents Volume 29, Number I (2017) Religious Offerings in the Ancient Near East (Aram Conference 2015) Dr. -

Land Dispossession and Its Impact on Agriculture Sector and Food Sovereignty in Palestine: a New Perspective on Land Day

Land dispossession and its impact on agriculture sector and food sovereignty in Palestine: a new perspective on Land Day Inès Abdel Razek-Faoder and Muna Dajani On 30 March 1976, 37 years ago, in response to the Israeli government's announcement of a plan to expropriate thousands of dunams1 of land for "security and settlement purposes" on the lands of Galilee villages of Sakhnin and Arraba, Dair Hanna, Arab Alsawaed and other areas thousands of people took the street to protest, calling for a general strike as a peaceful mean to resisting colonization and government plans of judaization of the Galilee. Six Palestinians in Israel were killed. A month later the Koenig2 Memorandum was leaked to the press recommending, for “national interest”, “the possibility of diluting existing Arab population concentrations”. Land Day has been since then commemorated in all Palestine as a day of steadfastness and resistance. It became a symbol of the refusal of the Palestinians to leave their homeland, and to reject any form of ethnic cleansing and pressures for displacement. It is a day of attachment to freedom, on both sides of the Green Line and in all corners of the world. On this occasion, 37 years later, there is a necessity to highlight the consequences of this systematic illegal dispossession and control over the land and its natural resources on farming and agriculture. Farming has been fundamental in Palestinian identity and history, deeply rooted in the culture of land and of the struggle for freedom since the beginning of the 20th century. Predominantly an agricultural community, Palestine has been transformed from depending on its systems of self-sufficiency farming to the industrial chemical agriculture of today, all this under a brutal occupation depriving farmers of their land and water resources. -

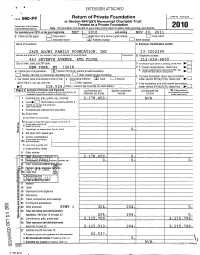

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

d I EXTENSION ATTACHED Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2010 Internal Revenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2010 , or tax year beginning DEC 1, 2010 and ending NOV 3 0, 2011 G Check all that apply. Initial return Initial return of a former public charity Ej Final return 0 Amended return ® Address chanae Name change Name of foundation A Employer identification number JACK ADJMI FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 13-3202295 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/swte B Telephone number 463 SEVENTH AVENUE , 4TH FLOOR 212-629-960 0 City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here NEW YORK , NY 10 018 D 1- Foreign organizations, check here 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation charitable Other taxable foundation Section 4947(a )( 1 ) nonexem pt trust 0 private E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, col. (c), line 16) = Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 111114 218 5 2 4 . (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507 b 1 B , check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b) (c), and (d) may not for charitable purposes necessarily equal the amounts in column (a)) expenses per books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received 2 , 178 , 450. -

Statistical Handbook of Middle Eastern Countries, Palestine, Cyprus, Egypt

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/statisticalhandbOOjewi JEWISH AGENCY FOR PAI^ESTINE ECONOMIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE STATISTICAL HANDBOOK OF MIDDLE EASTERN COUNTRIES PALESTINE, CYPRUS, EGYPT, IRAQ, THE LEBANON, SYRIA, TRANSJORDAN, TURKEY JERUSALEM, 1945 DISTRIBUTOR: D. B. AARONSON, P. O. B. 1175, JERUSALEM FOREWORD TO SECOND EDITION. This Handbook went out of print shortly after its first appearance, and a second edition was decided upon in response to numerous requests. In addition to the correction of certain misprints, the present issue includes an outline table as well as a supplement contaming new figures which have meanwhile become available. These additional statistics have been given the same serial numbers as the corresponding tables in the main text. The footnote signs are likewise those of the main tables. Suggestions for improvements or amendments to be included in any later edition will be appreciated. Jerusalem, April 1945. A. B. Copyright 1 944 by ihe Economic Research Institute of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, Jerusalem. Reprinted (with additions), 1945. Printed in Palestine by Stereotypes at tbe Azriel Printing Works, Jerusalem. -' PREFACE. -5 Modern economic policy has become almost entirely dependent on re- liable information regarding the processes and tendencies of economic and social life, which has been reduced to numerical statements and relationships. The growing complexity of modern society, the close connections to be found between the priyate and public fields of economy, the degree to which Government finance is dependent on foreign trade, employment, price level and other indices of economic development — all these make it necessary for the figures and data of economic and social life to be constantly available if state and political activities are to be successfully conducted nowadays. -

DATA COLLECTION SURVEY on WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT and AGRICULTURE IRRIGATION in the REPUBLIC of IRAQ FINAL REPORT April 2016 the REPUBLIC of IRAQ

DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND AGRICULTURE IRRIGATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ FINAL REPORT April 2016 REPORT IRAQ FINAL THE REPUBLIC OF IN IRRIGATION AGRICULTURE AND RESOURCE MANAGEMENT WATER ON COLLECTION SURVEY DATA THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AND AGRICULTURE IRRIGATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF IRAQ FINAL REPORT April 2016 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) NTC International Co., Ltd. 7R JR 16-008 英文 118331.402802.28.4.14 作業;藤川 Directorate Map Dohuk N Albil Nineveh Kiekuk As-Sulaymaniyyah Salah ad-Din Tigris river Euphrates river Bagdad Diyala Al-Anbar Babil Wasit Karbala Misan Al-Qadisiyan Al-Najaf Dhi Qar Al-Basrah Al-Muthanna Legend Irrigation Area International boundary Governorate boundary River Location Map of Irrigation Areas ( ii ) Photographs Kick-off meeting with MoWR officials at the conference Explanation to D.G. Directorate of Legal and Contracts of room of MoWR MoWR on the project formulation (Conference room at Both parties exchange observations of Inception report. MoWR) Kick-off meeting with MoA officials at the office of MoA Meeting with MoP at office of D.G. Planning Both parties exchange observations of Inception report. Both parties discussed about project formulation Courtesy call to the Minister of MoA Meeting with representatives of WUA assisted by the JICA JICA side explained the progress of the irrigation sector loan technical cooperation project Phase 1. and further project formulation process. (Conference room of MoWR) ( iii ) Office of AL-Zaidiya WUA AL-Zaidiya WUA office Site field work to investigate WUA activities during the JICA team conducted hearing investigation on water second field survey (Dhi-Qar District) management, farming practice of WUA (Dhi-Qar District) Piet Ghzayel WUA Piet Ghzayel WUA Photo shows the eastern portion of the farmland. -

Study on Small-Scale Agriculture in the Palestinian Territories Final

Study on Small-scale Agriculture in the Palestinian Territories Final Report Jacques Marzin. Cirad ART-Dév Ahmad Uwaidat. MARKAZ-Co Jean Michel Sourrisseau. CIRAD ART-Dév Submitted to: The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) June 2019 ACRONYMS ACAD Arab Center for Agricultural Development CIRAD Centre International de Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations GDP Gross National Product LSS Livestock Sector Strategy MoA Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture NASS National Agricultural Sector Strategy NGO Non-governmental organization PACI Palestinian Agricultural Credit Institution PCBS Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics PNAES Palestinian National Agricultural Extension Strategy PARPIF Palestinian Agricultural Risk Prevention and Insurance Fund SDGs Sustainable Development Goals (UN) SSFF Small-scale family farming UNHRC United Nations human rights council WFP World Food Programme 1 CONTENTS General introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and objectives of the study ...................................................................................................................... 5 Empirical material for this study ........................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgement and disclaimer ....................................................................................................................