Accusations of Unfairness Bias Subsequent Decisions: a Study of Major League Umpires Authors: Travis J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Problematic Use of Criminal Law to Regulate Sports Violence

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 99 Article 4 Issue 3 Spring Spring 2009 The aM nly Sports: The rP oblematic Use of Criminal Law to Regulate Sports Violence Jeffrey Standen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey Standen, The aM nly Sports: The rP oblematic Use of Criminal Law to Regulate Sports Violence, 99 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 619 (2008-2009) This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/09/9903-0619 THE JOURNALOF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 99, No. 3 Copyright © 2009 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printedin U.S.A. THE MANLY SPORTS: THE PROBLEMATIC USE OF CRIMINAL LAW TO REGULATE SPORTS VIOLENCE With increasingfrequency, the criminal law has been used to punish athletes who act with excessive violence while playing inherently violent sports. This development is problematicas none of the theories that courts employ to justify this intervention adequately take into account the expectations of participantsand the interests of the ruling bodies of sports. This Essay proposes a standardfor the interaction of violent sports and criminal law that attempts to reconcile the rules of violent sports with the aims of the criminal law. JEFFREY STANDEN* I. INTRODUCTION When not on the playing field, an athlete stands in the same relation to the criminal law as does any other citizen.1 The particular requirements of the athlete's sport, where that sport includes acts of a violent nature, do not supply the athlete a special defense of "diminished capacity. -

New York University Intramural Department Team Handball Rules

New York University Intramural Department Team Handball Rules Team Rules and Responsibilities 1. Teams must start or finish (due to injury or ejection) with three (3) players minimum. Four players are ideal to play (including the goalie). 2. Forfeits: Any team without the minimum four (4) players on the designated playing court of the scheduled start time and further exceeds the 5 minute grace period, will be disqualified from the game and future play in the league. 3. ONLY the team captain may consult with the referees or supervisor when the ball is NOT in play. 4. Substitutions can only be made during timeouts, after fouls and violations, or if the ball goes out of bounds. If this is not followed, a technical foul will be called and a penalty throw will be awarded. 5. Unsportsmanlike conduct against a scorekeeper, referee, any opposing player, or a teammate, a rejection from the game will occur. 6. Any team using an ineligible player will forfeit all remaining games on the schedule and will be removed from the league. 7. No player may play for more than one team. 8. Teams and players are susceptible to being barred from the playoffs. 9. Players who receive red cards during play will be ejected from the contest and possibly suspended for the following game. 10. ALL players are expected to display sportsmanlike conduct in compliance with NYU Intramurals. Equipment 1. Proper attire in line with Intramural policies, regulations, and guidelines is required – only non- marking sneakers, shorts or sweatpants must be worn to participate. 2. -

11-Player Youth Tackle Rules Guide Table of Contents

FOOTBALL DEVELOPMENT MODEL usafootball.com/fdm 11-PLAYER YOUTH TACKLE RULES GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .....................................................................................................2 1 Youth Specific Rules ..........................................................................3 2 Points of Emphasis ............................................................................4 3 Timing and Quarter Length ...........................................................5 4 Different Rules, Different Levels ..................................................7 5 Penalties ..................................................................................................7 THANK YOU ESPN USA Football sincerely appreciates ESPN for their support of the Football Development Model Pilot Program INTRODUCTION Tackle football is a sport enjoyed by millions of young athletes across the United States. This USA Football Rules Guide is designed to take existing, commonly used rule books by the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) and the NCAA and adapt them to the youth game. In most states, the NFHS rule book serves as the foundational rules system for the youth game. Some states, however, use the NCAA rule book for high school football and youth leagues. 2 2 / YOUTH-SPECIFIC RULES USA Football recommends the following rules be adopted by youth football leagues, replacing the current rules within the NFHS and NCAA books. Feel free to print this chart and provide it to your officials to take to the game field. NFHS RULE NFHS PENALTY YARDAGE USA FOOTBALL RULE EXPLANATION 9-4-5: Roughing/Running Into the Roughing = 15; Running Into = 5 All contact fouls on the kicker/holder Kicker/Holder result in a 15-yard penalty (there is no 5-yard option for running into the kicker or holder). 9-4-3-h: Grasping the Face Mask Grasping, pulling, twisting, turning = 15; All facemask fouls result in a 15-yard incidental grasping = 5 penalty (there is no 5-yard option for grasping but not twisting or pulling the facemask). -

Individual Officiating Techniques (IOT) Version 1.1 This Referees Manual Is Based on FIBA Official Basketball Rules 2020

FIBA REFEREES MANUAL Individual Officiating Techniques (IOT) version 1.1 This Referees Manual is based on FIBA Official Basketball Rules 2020. In case of discrepancy between different language editions on the meaning or interpretation of a word or phrase, the English text prevails. The content cannot be modified and presented with the FIBA logo, without written permission from the FIBA Referee Operations. Throughout the Referees Manual, all references made to a player, coach, referee, etc., in the male gender also apply to the female gender. It must be understood that this is done for practical reasons only. August 2020, All Rights Reserved. FIBA - International Basketball Federation 5 Route Suisse, PO Box 29 1295 Mies Switzerland fiba.basketball Tel: +41 22 545 00 00 Fax: +41 22 545 00 99 This material is created by the FIBA Referee Operations. If you identify an error or a discrepancy in this material,please notify the FIBA Referee Operations at [email protected] FIBA REFEREES MANUAL Individual Officiating Techniques / v1.0 P / 2 Foreword Basketball, as a game, is progressing in skill and speed every day. It is a natural environmental development process that takes place unconditionally and it is called evolution. The game and more so refereeing has completely changed from 10 years ago. Presently, top level refereeing is improving at least at the same speed as the game itself and higher standards of performance are expected every year. The pace of change has necessitated the adoption of a motto: “What was considered exceptionally good yesterday, is considered standard quality today and below average quality tomorrow”. -

Referee Hand Signals and Cheat Sheet

Referee Hand Signals and Cheat Sheet Types (T) (I=Procedural, P=Personal Foul, T=Technical Foul) Signal Text Penalty T Duration Comments Timeout: None I Up to 2 minutes. Possession required if Discretionary or Injury. RULE: 4 per game. not a dead ball. Follow with tapping on 4-27 Max 2 per half. chest for my TO. 4-28 Score None I Made by Lead Official. Retrieve ball and place at X. Check the penalty box after a goal. No Score None I End of period horn, goal-crease violation, 4-9 too many players, teams offside, whistle, head off stick, play on or foul by scoring team, timeout. Face-Off None I 4-3 Alternate Possession Possession I Must be recorded on the scorecard. 4-33 Ball in Possession on None I Attack/Defense must Face-off or start the stay out of center area clock at Half. until called. Ball has entered attack None I Occurs within 10 seconds of Must stay in the attack area. crossing the midline. area during the last 2 4-14 minutes of regulation 4-15 play. ONLY IN 4TH QTR 3-3 & TO TEAM THAT'S LEADING. Out of Bounds. Possession I Don’t forget to look to Direction of Play. bench for sub opportunity. NOT ON ENDLINE. Failure to Advance the Possession I 20 seconds (including 4 Player must be in Ball. second goalie count) to the contact with some part midline of the midline area. 10 seconds to the goal area. Airborne players do not count. Loose Ball I A call is made and the ball is not in possession of a player. -

1 Golden Strip Baseball / Softball Rules and Regulations – Revised 2/16/21

Baseball & Softball 2 nd -8th Rules and Regulations Playing rules not specifically covered in this document shall be covered by the Official Rules & Regulations of the South Carolina High School Baseball and Softball Leagues. Table of Contents Balks …………………………………………….……………………………………………………………………. 2 Balls ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Base lines ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Base Stealing ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Bats ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 2 Batting ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Batting Order ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Batting out of turn …………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Bunting ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Calling "Time" to Stop Play ……………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Catcher’s equipment …………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Cleats ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Coaches ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Complete Game …………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Courtesy Runners …………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Defensive Substitution ……………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Dropped Third Strike …………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Dugouts ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Ejection ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4 Forfeits ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Head First Slide …………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Helmets ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Infield Fly Rule …………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Intentional Walks …………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Number -

Violence in Professional Sports: Is It Time for Criminal Penalties?

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 2 Number 1 Article 5 1-1-1982 Violence in Professional Sports: Is it Time for Criminal Penalties? Richard B. Perelman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard B. Perelman, Violence in Professional Sports: Is it Time for Criminal Penalties?, 2 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 75 (1982). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol2/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIOLENCE IN PROFESSIONAL SPORTS: IS IT TIME FOR CRIMINAL PENALTIES? By RichardB. Perelman* I. INTRODUCTION The problem is well-known among sports fans. Violence in pro- fessional sporting events has reached almost epidemic proportions. Al- most all daily newspapers report about hundreds of penalty minutes for brawls in National Hockey League (NHL) games, fistfights in National Basketball Association (NBA) contests and about injuries suffered in National Football League (NFL) battles.' Recent commentary has ex- amined new case law in the area2 and the possibility of civil suit to redress damage.3 The criminal law confronted the problem in the form of a bill introduced in 1980 in the House of Representatives by Rep. Ronald M. Mottl.4 The bill would have penalized convicted offenders * B.A., University of California, Los Angeles, 1978. -

Major League Baseball Local Rules

West Madison Little League - Spring/Summer 2021 MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL LOCAL RULES All national Little League rules for Major League baseball, as described in the current season rulebook, apply unless specifically changed in these local rules or by past WMLL custom. The WMLL Safety Plan contains further regulations which will be enforced as local rules. Note: Rules of emphasis are indicated with blue text & new/modified rules in red text. TEAM RESPONSIBILITIES HOME TEAM RESPONSIBILITIES: The home team occupies the first base dugout & must: - Provide two new regulation balls - Arrange for a volunteer to help in the concession stand. VISITING TEAM RESPONSIBILITIES: The visiting team occupies the third base dugout & must: - Provide a volunteer to operate the scoreboard. RESPONSIBILITIES SHARED BY BOTH TEAMS: - Player Shortages/Replacement Players: If a team expects to be short of players (fewer than ten players) for a game, the head coach should obtain replacement players to add to the roster for that game, unless the team is short on players due to a scheduled school event in May or June. If this occurs, the head coach should contact the league coordinator so that the game can be rescheduled. • Replacement players must be ten-year-old players from WMLL’s Minor League. Coaches should contact potential replacement players directly. WMLL’s goal is to allow as many players as practical the opportunity of play up. Consequently, teams should try not to use the same call up more than two times during the season. • Replacement player(s) may not pitch and must bat last in the batting order. -

Ejection Penalties Increased

BASEBALL 2013 A supplement to the NCAA Baseball Rules • Prepared by the editors of Referee Ejection Penalties Increased he NCAA Baseball Rules Commit- Ttee tracked the number of ejections during the 2012 season and more than 600 combined ejections were reported for all three divisions. Of those ejec- tions, more than half were either as- sistant coaches or players. Since NCAA rules state that only head coaches are permitted to discuss calls with umpires, the committee strengthened the penalties that non- head coaches will receive as a result of an ejection. “In my view, the number of ejections is a major concern but the levels of unsportsmanlike conduct for many of them are unacceptable regardless of total number,” said Gene McArtor, the Division I national coordinator for umpires. “I will continue to believe that other than ‘that’s just the way it is in baseball,’ no one can justify hurting the image of college baseball by these actions.” Starting in 2013, all non-head coaching team personnel who are ejected for disputing an umpire’s call will receive a one-game suspension for the first ejection of the season and a three-game suspension for Only the head coach is allowed to come on to the fi eld to discuss a play with an umpire. Assistant any subsequent ejections during the coaches and players are not allowed to argue calls. season (2-25). Those suspensions are applicable leaving his position to dispute a call. of the season. Ruling 2: R3 is not only to ejections for disputing, It is the coach’s first ejection of the suspended because his ejection did arguing or unsportsmanlike conduct season. -

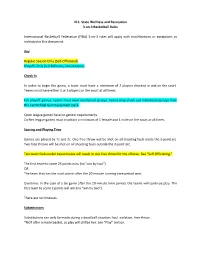

FIBA) 3-On-3 Rules Will Apply with Modifications Or Exceptions As Indicated in This Document

N.C. State Wellness and Recreation 3-on-3 Basketball Rules International Basketball Federation (FIBA) 3-on-3 rules will apply with modifications or exceptions as indicated in this document. Key Regular Season Only (Self-Officiated) Playoffs Only (1-2 Referees, Scorekeeper) Check In In order to begin the game, a team must have a minimum of 2 players checked in and on the court. Teams must have either 2 or 3 players on the court at all times. For playoff games, teams must wear numbered jerseys. Teams may check out intramural jerseys from the Carmichael Gym Equipment Desk. Open league games have no gender requirements. Co-Rec league games must maintain a minimum of 1 female and 1 male on the court at all times. Scoring and Playing Time Games are played by 1s and 2s. One free throw will be shot on all shooting fouls inside the 3-point arc. Two free throws will be shot on all shooting fouls outside the 3-point arc. Two team fouls under two minutes will result in one free throw for the offense. See “Self-Officiating.” The first team to score 25 points wins (no “win by two”) OR The team that has the most points after the 20-minute running time period wins. Overtime: In the case of a tie game after the 20-minute time period, the teams will continue play. The first team to score 2 points will win (no “win by two”). There are no timeouts. Substitutions Substitutions can only be made during a dead ball situation: foul, violation, free throw. -

Ejection Patterns

Ejections Through the Years and the Impact of Expanded Replay Ejections are a fascinating part of baseball and some have led to memorable confrontations, several of which are readily accessible in various electronic archives. Perhaps surprisingly, reliable information on ejections has been available only sporadically and there are many conflicting numbers in both print and on-line for even the most basic data such as the number of times a given player, manager or umpire was involved. The first comprehensive compilation of ejection data was carried out over many years by the late Doug Pappas, a tireless researcher in many areas of baseball, including economic analyses of the game. He not only amassed the details of over 11,000 ejections, he also lobbied intensely to have ejection information become a standard part of the daily box scores. He was successful in that effort and we have him to thank for something we now take for granted. After Doug’s passing, his ejection files made their way to Retrosheet where they were maintained and updated by the late David Vincent who expanded the database to over 15,000 events. In 2015, David used the expanded data in the Retrosheet files as the basis for an article which provided some fine background on the history of ejections along with many interesting anecdotes about especially unusual occurrences ((https://www.retrosheet.org/Research/VincentD/EjectionsHistory.pdf). Among other things, David noted that ejections only began in 1889 after a rule change giving umpires the authority to remove players, managers, and coaches as necessary. Prior to that time, offensive actions could only be punished by monetary fines. -

NCAA and NFHS Major Basketball Rules Differences

2020-21 MAJOR BASKETBALL RULES DIFFERENCES (Men’s and Women’s) ITEM NFHS NCAA Administrative Warnings Issued for non-major infractions of coaching- Men – Only for the head coach being outside the box rule, disrespectfully addressing an official, coaching box and certain delay-of-game situations. attempting to influence an official’s decision, Women – Same as Men plus minor conduct inciting undesirable crowd reactions, entering violations of misconduct guidelines by any bench the court without permission, or standing at the personnel. team bench. Bonus Free Throws One-and-One Bonus On the seventh team foul. Men – Same as NFHS. Women – No one-and-one bonus. Double Bonus On the 10th team foul. Men – Same as NFHS. Women – On fifth team foul. Team Fouls Reset End of the first half. Men – Same as NFHS. Women – End of first, second and third periods. Blood/Contacts Player with blood directed to leave game (may Men – Player with blood may remain in game if remain in game with charged time-out); player remedied within 20 seconds. Lost/irritated contact with lost/irritated contacts may remain in game within reasonable time. with reasonable time to correct. Women – Player with may remain in game if remedied within 20 seconds or charged timeout to correct blood or contacts. Coaching Box Size State option, 28-foot box maximum. Both – Extends from 38-foot line to end line. Loss of Use If head coach is charged with a direct or indirect Both – No rule. technical foul. Delay-of-Game Warnings One warning for any of the four delay-of-game Men – One warning for any of the four delay-of- situations; subsequent delay for any of four game situations; a repeated warning for the same results in a technical foul.