The Philosophy of Zoology Before Darwin. a Translated And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buzzle – Zoology Terms – Glossary of Biology Terms and Definitions Http

Buzzle – Zoology Terms – Glossary of Biology Terms and Definitions http://www.buzzle.com/articles/biology-terms-glossary-of-biology-terms-and- definitions.html#ZoologyGlossary Biology is the branch of science concerned with the study of life: structure, growth, functioning and evolution of living things. This discipline of science comprises three sub-disciplines that are botany (study of plants), Zoology (study of animals) and Microbiology (study of microorganisms). This vast subject of science involves the usage of myriads of biology terms, which are essential to be comprehended correctly. People involved in the science field encounter innumerable jargons during their study, research or work. Moreover, since science is a part of everybody's life, it is something that is important to all individuals. A Abdomen: Abdomen in mammals is the portion of the body which is located below the rib cage, and in arthropods below the thorax. It is the cavity that contains stomach, intestines, etc. Abscission: Abscission is a process of shedding or separating part of an organism from the rest of it. Common examples are that of, plant parts like leaves, fruits, flowers and bark being separated from the plant. Accidental: Accidental refers to the occurrences or existence of all those species that would not be found in a particular region under normal circumstances. Acclimation: Acclimation refers to the morphological and/or physiological changes experienced by various organisms to adapt or accustom themselves to a new climate or environment. Active Transport: The movement of cellular substances like ions or molecules by traveling across the membrane, towards a higher level of concentration while consuming energy. -

Glossary - Zoology - Intro

1 Glossary - Zoology - Intro Abdomen: Posterior part of an arthropoda’ body; in vertebrates: abdomen between thorax and pelvic girdle. Acoelous: See coelom. Amixia: A restriction that prevents general intercrossing in a species leading to inbreeding. Anabiosis: Resuscitation after apparent death. Archenteron: See coelom. Aulotomy: Capacity of separating a limb; followed by regeneration; used also for asexual reproduction; see also fissipary (in echinodermata and platyhelminthes). Basal Lamina: Basal plate of developing neural tube; the noncellular, collagenous layer that separates an epithelium from an underlying layer of tissue; also basal membrane. Benthic: Organisms that live on ocean bottoms. Blastocoel: See coelom. Blastula: Stage of embryonic development, at / near the end of cleavage, preceding gastrulation; generally consisting of a hollow ball of cells (coeloblastula); if no blastoceol is present it is termed stereoblastulae (arise from isolecithal and moderately telolecithal ova); in meroblastic cleavage (only the upper part of the zygote is divided), the blastula consists of a disc of cells lying on top of the yolk mass; the blastocoel is reduced to the space separating the cells from the yolk mass. Blastoporus: The opening into the archenteron (the primitive gastric cavity of the gastrula = gastrocoel) developed by the invagination of the blastula = protostoma. Cephalisation: (Gk. kephale, little head) A type of animal body plan or organization in which one end contains a nerve-rich region and functions as a head. Cilium: (pl. cilia, long eyelash) A short, centriole-based, hairlike organelle: Rows of cilia propel certain protista. Cilia also aid the movement of substances across epithelial surfaces of animal cells. Cleavage: The zygote undergoes a series of rapid, synchronous mitotic divisions; results in a ball of many cells. -

Biology Has Been Taught at Bristol – As Botany and Zoology – Since Before the University Was Founded in 1909

Biology has been taught at Bristol – as Botany and Zoology – since before the University was founded in 1909. Bristol has made significant contributions to many fields, from animal cognition and medicinal plants to entomology, evolutionary Game Theory and bird flight – and the BBC Natural History Unit's proximity to the University has led to television careers for a number of graduates! In 1876, University College, the precursor to the University, appointed Dr. Frederick Adolph Leipner as Lecturer in Botany, Zoology and, amusingly, German. Leipner had trained at the Bristol Medical School, but taught botany and natural philosophy, later combining this with teaching in Vegetable Physiology at the Medical School. He became Professor of Botany in 1884 and was a founding member of the Bristol Naturalists' Society, becoming its President in 1893. Bristol today is proud of its interdisciplinary strengths and, among others, offers Joint Honours Degrees in Geology and Biology, and in Psychology and Zoology. A portent of these modern links is seen in one of the University's most notable early appointments, Conwy Lloyd Morgan, appointed as Professor of Zoology and Geology in 1884 and then – somehow fitting in service as Vice- Chancellor – becoming the first Chair in Psychology (and Ethics). Lloyd Morgan is most famous as a pioneer of the study of comparative animal cognition. He was a highly influential figure for the North American Behaviourist movement: “Lloyd Morgan's cannon” is a comparative psychologist's version of Occam's Razor whereby no behaviour should be ascribed to more complex cognitive mechanisms than strictly necessary. He was the first Fellow of the Royal Society to be elected for psychological work. -

(LOCF) for (ZOOLOGY) Undergraduate Programme: a Template 2019

Learning Outcomes based Curriculum Framework (LOCF) for (ZOOLOGY) Undergraduate Programme: A template 2019 UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI – 110 002 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... 2 Preamble .................................................................................................................................... 6 Foreword .................................................................................................................................... 9 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 10 2. Learning Outcome Based approach to Curriculum Planning ............................................... 10 2.1 Nature and extent of the B.Sc degree Programme in Zoology ......................................... 11 2.2. Aims of Bachelor’s Degree Programme in Zoology ......................................................... 11 3. Graduate Attributes in Zoology ..................................................................................................... 12 4. Qualification Descriptors for a Bachelor’s Degree Programme in Zoology.....................14 5. Learning Outcomes in Bachelor’s Degree Programme in Zoology…………………..15 5.1 Knowledge and Understanding ...................................................................................................... 15 -

History of Zoology Since 1859

History of zoology since 1859 This article considers the history of zoology since the Asian zone and a New Guinea/Australian zone. His key theory of evolution by natural selection proposed by question, as to why the fauna of islands with such similar Charles Darwin in 1859. climates should be so different, could only be answered by Charles Darwin gave new direction to morphology and considering their origin. In 1876 he wrote The Geograph- ical Distribution of Animals, which was the standard ref- physiology, by uniting them in a common biological the- ory: the theory of organic evolution. The result was erence work for over half a century, and a sequel, Island Life, in 1880 that focused on island biogeography. He a reconstruction of the classification of animals upon a genealogical basis, fresh investigation of the development extended the six-zone system developed by Philip Sclater of animals, and early attempts to determine their genetic for describing the geographical distribution of birds to relationships. The end of the 19th century saw the fall animals of all kinds. His method of tabulating data on an- of spontaneous generation and the rise of the germ the- imal groups in geographic zones highlighted the disconti- ory of disease, though the mechanism of inheritance re- nuities; and his appreciation of evolution allowed him to propose rational explanations, which had not been done mained a mystery. In the early 20th century, the redis- [2][3] covery of Mendel’s work led to the rapid development of before. genetics by Thomas Hunt Morgan and his students, and The scientific study of heredity grew rapidly in the wake by the 1930s the combination of population genetics and of Darwin’s Origin of Species with the work of Francis natural selection in the "neo-Darwinian synthesis". -

Ecology and Environmental Biology (Zoology-II) [B.Sc

Biyani's Think Tank Concept based notes Ecology and Environmental Biology (Zoology-II) [B.Sc. Part-III] Smita Singh Ph.D, M.Sc. Lecturer Deptt. of Information Technology Biyani Girls College, Jaipur 2 Published by : Think Tanks Biyani Group of Colleges Concept & Copyright : Biyani Shikshan Samiti Sector-3, Vidhyadhar Nagar, Jaipur-302 023 (Rajasthan) Ph : 0141-2338371, 2338591-95 Fax : 0141-2338007 E-mail : [email protected] Website :www.gurukpo.com; www.biyanicolleges.org ISBN : 978-93-81254-00-4 Edition : 2011 Price : While every effort is taken to avoid errors or omissions in this Publication, any mistake or omission that may have crept in is not intentional. It may be taken note of that neither the publisher nor the author will be responsible for any damage or loss of any kind arising to anyone in any manner on account of such errors and omissions. Leaser Type Setted by : Biyani College Printing Department Ecology and Environmental Biology 3 Preface am glad to present this book, especially designed to serve the needs of I the students. The book has been written keeping in mind the general weakness in understanding the fundamental concepts of the topics. The book is self- explanatory and adopts the “Teach Yourself” style. It is based on question- answer pattern. The language of book is quite easy and understandable based on scientific approach. Any further improvement in the contents of the book by making corrections, omission and inclusion is keen to be achieved based on suggestions from the readers for which the author shall be obliged. I acknowledge special thanks to Mr. -

EDU246, Ecology and Applied Zoology, Biodiversity.Pdf

Department of zoology Course code-EDU249 Course name-Ecology and applied zoology Biodiversity and its importance The earth holds a vast diversity of living organisms, which includes different kinds of plants, animals, insects, and microorganisms. The earth also holds an immense variety of habitats and ecosystems. The total diversity and variability of living things and of the system of which they are a part is generally defined as biological diversity, i.e. the total variability of life on earth. In other words it also refers to the totality of genes, species and ecosystems in a region. Biodiversity includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems. It can be partitioned, so that we can talk of the biodiversity of a country, of an area, or an ecosystem, of a group of organisms, or within a single species. The term biodiversity, the short form of biological diversity, was coined by Walter G. Rosen in 1985, however the origin of the concept go far back in time. Perception of biodiversity varies widely among different segments, such as biologists, sociologists, lawyers, naturalists, conservationists, ethnobiologists and so on. Thus, biodiversity issues have been unifying force among people of various professions and pursuits. Biodiversity represents the very foundation of human existence. Besides the profound ethical and aesthetic implications, it is clear that the loss of biodiversity has serious economic and social costs. The genes, species, ecosystems and human knowledge which are being lost represent a living library of options available for adapting to local and global change. Biodiversity is part of our daily lives and livelihood and constitutes the resources upon which families, communities, nations and future generations depend. -

History of Biology - Alberto M

BIOLOGICAL SCIENCE FUNDAMENTALS AND SYSTEMATICS – Vol. I – History of Biology - Alberto M. Simonetta HISTORY OF BIOLOGY Alberto M. Simonetta Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e Genetica, “L. Pardi,” University of Firenze, Italy Keywords: Biology, history, Antiquity, Middle ages, Renaissance, morphology, palaeontology, taxonomy, evolution, histology, embryology, genetics, ethology, ecology, pathology Contents 1. Introduction 2. Antiquity 3. The Medieval and Renaissance periods 4. The Development of Morphology 5. Paleontology 6. Taxonomy and Evolution 7. Histology, Reproduction, and Embryology 8. Physiology 9. Genetics 10. Ecology and Ethology 11. Pathology Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary A short account is given of the development of biological sciences from their Greek origins to recent times. Biology as a pure science was the creation of Aristotle, but was abandoned shortly after his death. However, considerable advances relevant for medicine continued to be made until the end of classical times, in such fields as anatomy and botany. These developments are reviewed. After a long pause, both pure and applied research began anew in the thirteenth century, and developedUNESCO at an increasing pace therea fter.– However, EOLSS unlike astronomy and physics, which experienced a startling resurgence as soon as adequate mathematical methods and instruments became available, the development of biology was steady but slow until the appearance of Darwin’s revolutionary ideas about evolution brought about a fundamental shiftSAMPLE in the subject’s outlook. TheCHAPTERS efflorescence of biological sciences in the post-Darwinian period is outlined briefly. 1. Introduction To outline more than 2000 years of biology in a few pages is an extremely difficult endeavor as, quite apart from the complexities of both the subject itself and of the technical and theoretical approaches of various scholars, the development of scholars’ views, ideas, and researches forms an intricate network that cannot be fully disentangled in such a brief account. -

Zoology Lab Manual

General Zoology Lab Supplement Stephen W. Ziser Department of Biology Pinnacle Campus To Accompany the Zoology Lab Manual: Smith, D. G. & M. P. Schenk Exploring Zoology: A Laboratory Guide. Morton Publishing Co. for BIOL 1413 General Zoology 2017.5 Biology 1413 Introductory Zoology – Supplement to Lab Manual; Ziser 2015.12 1 General Zoology Laboratory Exercises 1. Orientation, Lab Safety, Animal Collection . 3 2. Lab Skills & Microscopy . 14 3. Animal Cells & Tissues . 15 4. Animal Organs & Organ Systems . 17 5. Animal Reproduction . 25 6. Animal Development . 27 7. Some Animal-Like Protists . 31 8. The Animal Kingdom . 33 9. Phylum Porifera (Sponges) . 47 10. Phyla Cnidaria (Jellyfish & Corals) & Ctenophora . 49 11. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) . 52 12. Phylum Nematoda (Roundworms) . 56 13. Phyla Rotifera . 59 14. Acanthocephala, Gastrotricha & Nematomorpha . 60 15. Phylum Mollusca (Molluscs) . 67 16. Phyla Brachiopoda & Ectoprocta . 73 17. Phylum Annelida (Segmented Worms) . 74 18. Phyla Sipuncula . 78 19. Phylum Arthropoda (I): Trilobita, Myriopoda . 79 20. Phylum Arthropoda (II): Chelicerata . 81 21. Phylum Arthropods (III): Crustacea . 86 22. Phylum Arthropods (IV): Hexapoda . 90 23. Phyla Onycophora & Tardigrada . 97 24. Phylum Echinodermata (Echinoderms) . .104 25. Phyla Chaetognatha & Hemichordata . 108 26. Phylum Chordata (I): Lower Chordates & Agnatha . 109 27. Phylum Chordata (II): Chondrichthyes & Osteichthyes . 112 28. Phylum Chordata (III): Amphibia . 115 29. Phylum Chordata (IV): Reptilia . 118 30. Phylum Chordata (V): Aves . 121 31. Phylum Chordata (VI): Mammalia . 124 Lab Reports & Assignments Identifying Animal Phyla . 39 Identifying Common Freshwater Invertebrates . 42 Lab Report for Practical #1 . 43 Lab Report for Practical #2 . 62 Identification of Insect Orders . 96 Lab Report for Practical #3 . -

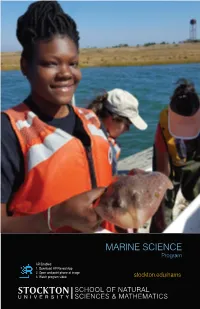

MARINE SCIENCE Program

MARINE SCIENCE Program AR Enabled 1. Download HP Reveal App 2. Open and point phone at image 3. Watch program video stockton.edu/nams Marine Science Program | MARS ABOUT THE PROGRAM Stockton University is located adjacent to the Jacques Cousteau National Estuarine Research Reserve (Mullica River-Great Bay estuary) and is one of only a few undergraduate institutions in the U.S. that offers a degree program in Marine Science alongside a dedicated, easily accessible field facility (Stockton Marine Field Station) www.stockton.edu/marine. With direct access to the Field Station only 10 minutes away, the program is well situated to provide superior field, teaching, and undergraduate research opportunities that form the backbone of the curriculum. Stockton’s Marine Science (MARS) program encompasses two general areas of study: Marine Biology and Oceanography. A number of field and laboratory courses, seminars, independent studies, internships, and research team opportunities are offered, with a strong emphasis on gaining experience in the field. The program is interdisciplinary and requires student competence in several areas of science. Upper-level students have the opportunity to design and implement their own independent study projects and are strongly encouraged to present results at the NAMS Undergraduate Research Symposium and regional conferences. Teacher (K-12) and GIS certifications are available through affiliated Stockton programs. The Marine Sciences tracks of study: Marine Biology, BA and BS, Oceanography, BA and BS Program Highlights • Small course sections taught primarily by full-time faculty (not by graduate assistants). • Every student is assigned a faculty member as their academic adviser (preceptor) • Faculty encourage and supervise internships and research projects. -

Zoology (ZOOLOGY) 1

Zoology (ZOOLOGY) 1 ZOOLOGY/BIOLOGY/BOTANY 152 — INTRODUCTORY BIOLOGY ZOOLOGY (ZOOLOGY) 5 credits. Second semester of a two semester course designed for majors in ZOOLOGY/BIOLOGY 101 — ANIMAL BIOLOGY biological sciences. Continuation of 151. Topics include: selected topics 3 credits. in plant physiology, a survey of the five major kingdoms of organisms, speciation and evolutionary theory, and ecology at multiple levels of the General biological principles. Topics include: evolution, ecology, animal biological hierarchy. Enroll Info: Biology/Botany/ZOOLOGY/BIOLOGY/ behavior, cell structure and function, genetics and molecular genetics BOTANY 151. Not recommended for students with credit already in and the physiology of a variety of organ systems emphasizing function in Zoology/BIOLOGY/ZOOLOGY 101,102 or Botany/BIOLOGY/BOTANY 130 humans. Enroll Info: Not recommended for students with credit already in Requisites: ZOOLOGY/BIOLOGY/BOTANY 151 Zoology/Biology/BOTANY/BIOLOGY/ZOOLOGY 151 or 152 Course Designation: Gen Ed - Communication Part B Requisites: None Breadth - Biological Sci. Counts toward the Natural Sci req Course Designation: Breadth - Biological Sci. Counts toward the Natural Level - Elementary Sci req L&S Credit - Counts as Liberal Arts and Science credit in L&S Level - Elementary Repeatable for Credit: No L&S Credit - Counts as Liberal Arts and Science credit in L&S Last Taught: Spring 2021 Repeatable for Credit: No Last Taught: Summer 2021 ZOOLOGY 153 — INTRODUCTORY BIOLOGY 3 credits. ZOOLOGY/BIOLOGY 102 — ANIMAL BIOLOGY LABORATORY 2 credits. One-semester course designed for engineering majors including chemical and biological engineering. Topics include: cell structure and function, General concepts of animal biology at an introductory level. -

Invertebrate Paleontology Earth Sciences Division Natural History

Invertebrate Paleontology 19^ Earth Sciences Division Natural History Mu 3311m A NEW SPECIES OF CHIMNEY-BUILDING PENITELLA FROM THE GULF OF ALASKA (BIVALVIA: PHOLADIDAE) * LIBRARY 'Ol ANGBIES GOIJNTV \i: A>., , -APOsrr.'ON GEORGE L. KENNEDY AND JOHN M. ARMENTROUT 1 Made in United States of America Reprinted from THE VELIGER Vol. 32, No. 3, July 1989 © California Malacozoological Society, Inc., 1989 THE VELIGER © CMS, Inc., 1989 The Veliger 32(3):320-325 (July 3, 1989) A New Species of Chimney-Building Penitella from the Gulf of Alaska (Bivalvia: Pholadidae) by GEORGE L. KENNEDY Invertebrate Paleontology Section, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA AND JOHN M. ARMENTROUT Mobil Oil Corporation, New Exploration Ventures, P.O. Box 650232, Dallas, Texas 75265, USA Abstract. Penitella hopkinsi sp. nov., from the Gulf of Alaska, differs from other species in the genus by its blunt and thickened posterior margin that inserts against the base of a chimney of agglutinated sediment (unique in the genus), by the shape of the mesoplax, and by details of the umbonal reflection and dorsal extension of the callum. Anatomy is unknown. Late Pleistocene records of the species range from the Seward Peninsula, Alaska, to Point Arena, California. INTRODUCTION acology]); MCZ, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cam- bridge; NMC, National Museum of Natural Sciences, Recent efforts to identify several enigmatic species of Peni- Ottawa; NSMT, National Science Museum, Tokyo; tella Valenciennes, 1846, from both the northeastern and SBMNH, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, northwestern Pacific revealed that a number of nomencla- Santa Barbara; UCLA, University of California, Los An- tural and taxonomic problems in the genus still need to geles (collections at LACM); UCMP, University of Cal- be resolved (KENNEDY, 1985).