Components of British Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JC445 Causeway Museum Emblems

North East PEACE III Partnership A project supported by the PEACE III Programme managed for the Special EU Programmes Body by the North East PEACE III Partnership. JJC445C445 CausewayCauseway Museum_EmblemsMuseum_Emblems Cover(AW).inddCover(AW).indd 1 009/12/20119/12/2011 110:540:54 Badge from the anti-home rule Convention of 1892. Courtesy of Ballymoney Museum. Tourism Poster. emblems Courtesy of Coleraine Museum. ofireland Everywhere we look we see emblems - pictures which immediately conjure connections and understandings. Certain emblems are repeated over and over in a wide range of contexts. Some crop up in situations where you might not expect them. The perception of emblems is not fi xed. Associations change. The early twentieth century was a time when ideas were changing and the earlier signifi cance of certain emblems became blurred. This leafl et contains a few of the better and lesser known facts about these familiar images. 1 JJC445C445 CCausewayauseway Museum_EmblemsMuseum_Emblems Inner.inddInner.indd 1 009/12/20119/12/2011 110:560:56 TheThe Harp HecataeusHecata of Miletus, the oldest known Greek historian (around 500BC),500BC) describes the Celts of Ireland as “singing songs in praise ofof Apollo,Apo and playing melodiously on the harp”. TheThe harpha has been perceived as the central instrument of ancientancient Irish culture. “The“Th Four Winds of Eirinn”. CourtesyCo of J & J Gamble. theharp The Image of the Harp Harps come in many shapes and sizes. The most familiar form of the Irish harp is based on the so called “Brian Boru’s Harp”. The story is that Brian Boru’s son gave it to the Pope as a penance. -

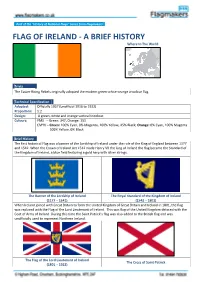

FLAG of IRELAND - a BRIEF HISTORY Where in the World

Part of the “History of National Flags” Series from Flagmakers FLAG OF IRELAND - A BRIEF HISTORY Where In The World Trivia The Easter Rising Rebels originally adopted the modern green-white-orange tricolour flag. Technical Specification Adopted: Officially 1937 (unofficial 1916 to 1922) Proportion: 1:2 Design: A green, white and orange vertical tricolour. Colours: PMS – Green: 347, Orange: 151 CMYK – Green: 100% Cyan, 0% Magenta, 100% Yellow, 45% Black; Orange: 0% Cyan, 100% Magenta 100% Yellow, 0% Black Brief History The first historical Flag was a banner of the Lordship of Ireland under the rule of the King of England between 1177 and 1542. When the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 made Henry VII the king of Ireland the flag became the Standard of the Kingdom of Ireland, a blue field featuring a gold harp with silver strings. The Banner of the Lordship of Ireland The Royal Standard of the Kingdom of Ireland (1177 – 1541) (1542 – 1801) When Ireland joined with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801, the flag was replaced with the Flag of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. This was flag of the United Kingdom defaced with the Coat of Arms of Ireland. During this time the Saint Patrick’s flag was also added to the British flag and was unofficially used to represent Northern Ireland. The Flag of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland The Cross of Saint Patrick (1801 – 1922) The modern day green-white-orange tricolour flag was originally used by the Easter Rising rebels in 1916. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

Zde Začněte Psát Svůj Text

THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is a country and sovereign state that lies to the northwest of Continental Europe with Ireland to the west. It occupies the majority of the British Isles and its territory and population are primarily situated on the island of Great Britain and in Northern Ireland on the island of Ireland. The United Kingdom is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean, and its ancillary bodies of water, including the North Sea, the English Channel, the Celtic Sea, and the Irish Sea. The mainland is linked to France by the Channel Tunnel, with Northern Ireland sharing a land border with the Republic of Ireland. The United Kingdom is a political union made up of four constituent countries: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The British crown has three dependencies: the Isle of Man, Guernsey and Jersey. The United Kingdom also has many overseas territories, including Anguilla, Bermuda,Gibraltar, Pitcairn Islands, British Indian Ocean Territory, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Falkland Islands, Gibraltar, Montserrat, Saint Helena (with Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha), South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, as well as Akrotiri and Dhekelia and British Antarctica among others. A constitutional monarchy, The Queen Elizabeth II is also the Queen and the Head of the State of 15 other Commonwealth Realms such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. People Nationality: British. Population (2008): 61.7 million. Annual population growth rate (2008 est.): 0.7%. Major ethnic groups: British, Irish, West Indian, South Asian. -

Reporting the UK Guidance

Last updated March 2021 Reporting the UK – Revised Guidance Key points Accurate reporting of the UK’s different governments and cultures is essential to the way our audiences view and judge the BBC’s output. We should respect and reflect the national and regional differences and sensitivities and report all parts of the UK accurately, consistently and fairly, avoiding stereotypes or clichés. Content producers should use correct terminology and pronunciation for the relevant part of the UK. Referrals to BBC National Directors Editorial Guidelines (2.4.3): Any content producers intending to produce output about Northern Ireland or significant projects involving the Republic of Ireland, should notify Director Northern Ireland of their proposals at an early stage. Content producers outside Scotland and Wales should inform the director of the relevant nation of their plans to produce programme material which is based in the relevant nation or which deals significantly with national issues or themes. General BBC programmes and services should be relevant and appropriate for all our audiences in all parts of the United Kingdom. Audiences approach our output in different ways and with different expectations because their lives are shaped by different: • cultural backgrounds • life experiences • civic and political institutions. We should respect and reflect the national and regional differences and sensitivities and report all parts of the UK accurately, consistently and fairly, avoiding stereotypes or clichés. Key differences We should note that varying differences exist between England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland which principally include: • the powers of their political institutions - Westminster, the Scottish Parliament, the Senedd – the Welsh Parliament, the Northern Ireland Assembly, the London Assembly and combined authorities. -

Band Practice: Class, Taste and Identity in Ulster Loyalist Flute Bands

Ethnomusicology Ireland 1 (2011) 1 BAND PRACTICE: CLASS, TASTE AND IDENTITY IN ULSTER LOYALIST FLUTE BANDS By Gordon Ramsey Introduction Parading to fife and drum has been part of working-class culture in Ulster since the 1780s, when the practice was popularised by part-time military forces such as the Volunteers and Yeomanry. 1 The marching flute-band became the dominant musical ensemble in parades by the turn of the 20th century, when many bands were sponsored by the mass political movements, nationalist and loyalist, mobilised by successive Home Rule crises. Many loyalist bands at this time were supported by lodges of the Protestant fraternity, the Orange Order, and found most of their performance opportunities at Orange parades. Today, the situation is radically different, with the vast majority of loyalist bands being independent of the Order, and Orange parades forming a very small proportion of their activities. In 2010, loyalist marching bands are more numerous, more active, and more central to the lives of their members than they have ever been. The level of participation is extraordinary, with over 700 bands active within the six counties of Northern Ireland,2 and bands also flourishing in the border counties of the Irish Republic, and in western Scotland. Over half of the bands within Northern Ireland are flute bands, with accordion, pipe, and brass or silver bands making up the remainder (Witherow 2008:47-8). Every weekend (and 1 Illustrations in various media to accompany this essay are accessible at the online version of this journal www.ictm.ie. An earlier version of the paper was first presented orally at the 5th ICTM Ireland Annual Conference, ‘Ensemble/Playing Together’, Limerick, 26-28 Feb. -

The Material Value of Flags: Politics and Space in Northern Ireland

The Material Value of Flags: Politics and Space in Northern Ireland Bryan, D. (2018). The Material Value of Flags: Politics and Space in Northern Ireland. Review of Irish Studies in Europe, 2(1), 76-91. http://www.imageandnarrative.be/index.php/rise/article/view/1708 Published in: Review of Irish Studies in Europe Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2018 The Authors. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:27. Sep. 2021 The Material Value of Flags: Politics and Space in Northern Ireland Dominic Bryan In the first two decades of the twenty first century one of the most distinctive features of a tour around the streets of Belfast or Derry/Londonderry or the rural roads of Northern Ireland is the proliferation of flags hanging from lampposts, telegraph poles, or indeed almost any prominent point from which visibility can be profiled. -

Basic Information

Basic information Northern Ireland lies in the north-east of the island of Ireland.It covers 14,139 square kilometres (5,459 square miles), and has a population of 1,685,000 (April 2001). •The capital city is Belfast. •Northern Ireland was created in 1921 as a home-rule political entity, under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. •People from Northern Ireland declare themselves as Irish and British •Official languages are Irish, Ulster Scots and English. History •The area now known as Northern Ireland has had a diverse history. •Northern Ireland was created in 1921 as a home-rule political entity, under the Government of Ireland 1920, along with the nominal state of Southern Ireland, which was superceded almost immediately after its creation by the Irish Free state. •When they achieved independence, they declined to join and so remained part of the United Kingdom under the procedures laid out in the Anglo-Irish Treaty 1921 •47% of the population is unionist and wishes to remain part of the United Kingdom, but a 41% minority, known as the nationalists want a re- United Ireland. The clashes between both sets of identity, and discrimination against nationalists by unionists, produced a violent struggle by minorities within both communities that ran from the late 1960s to the early 1990s and was known as The Troubles. •There are still many conflicts between unionists and nationalists, especially because of the IRA-e Irish Republican Army whose members want to unite Northern Ireland to the Republic of geographic nomenclature •Unionists often incorrectly call Northern Ireland "Ulster" or "the Province"; nationalists often use the terms the "North of Ireland" and the "Six Counties". -

1 Appendix Table of Contents Songs

1 Appendix Table of Contents Songs and Classifications 1 Selective Timeline 2 Belfast and Derry Religious Demographics 6 “The Men Behind The Wire” 7 Belfast Murals 8 Songs and Classifications When working with these songs, I divided them into four categories - Aggressive/Militant Support for the conflict (along with which side it seemed to support), Passive/Non-violent Support (also with which side), Aggressive/Militant Opposition, and Passive/Non-violent Opposition. While some of these divisions were fairly clear, others were based on personal interpretation. As such, this is a list of the music I looked at and which category I placed them in, both for easy reference and later research. AS - Aggressive Support PS - Passive Support AO - Aggressive Opposition PO - Passive Opposition N/R - Nationalist/Republican U/L - Unionist/Loyalist Unknown Date “The Sash My Father Wore” - Unknown Artist - Unknown Date - PS-U “Daddy’s Uniform” - Unknown Artist - Unknown Date - AS-L (I couldn’t find a solid date for either of these, but because the former may be from a nineteenth-century tune and the latter seems to be post-WWII in origin, I discussed them in the 1960s-70s category because presumably they were already known by that point.) 1960s-1970s “Only Her Rivers Run Free” - Mickey MacConnell - 1965 - PS-N “Four Green Fields” - Tommy Makem - 1967 - PS-N “The Men Behind the Wire” - Paddy McGuigan - 1971 - PS-N “The Men Behind the Wire” - Unknown - 1972 - PS-U “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” - Paul McCartney - 1972 - PO “Go On Home, British Soldiers” -

United States

Hanoi 191208 Wikipedia SyHung2020 United States From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses of terms redirecting here, see US (disambiguation), USA (disambiguation), and United States (disambiguation) The United States of America (commonly referred to as the United States, the U.S., the USA, or America) is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district. The country is situated mostly in central North America, where its forty-eight contiguous states and Washington, D.C., the capital district, lie between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, bordered by Canada to the north and Mexico to the south. The state of Alaska is in the northwest of the continent, with Canada to its east and Russia to the west across the Bering Strait. The state of Hawaii is an archipelago in the mid-Pacific. The country also possesses several territories, or insular areas, scattered around the Caribbean and Pacific. At 3.79 million square miles (9.83 million km²) and with about 305 million people, the United States is the third or fourth largest country by total area, and third largest by land area and by population. The United States is one of the world's most ethnically diverse and multicultural nations, the product of large-scale immigration from many countries.[7] The U.S. economy is the largest national economy in the world, with an estimated 2008 gross domestic product (GDP) of US$14.3 trillion (23% of the world total based on nominal GDP and almost 21% at purchasing power parity).[4][8] .. The nation was founded by thirteen colonies of Great Britain located along the Atlantic seaboard. -

The Ulster-Scot

win a giFt Card & an WIN...AWIN...FAMILAYFAPAMILSSWIN...ulster-YTOPAAW5!SSsCWIN...FAotsTOMIL goodyW5!AYFAPAMILSS Y TOPASSW5!TO W5! Ulster-ScotsUlster-ScotsAgency Agency(BoUlster-Scotsord o(BoUlstér-Scotch)ordAgencyo Ulstér-Scotch)(BoUlster-Scotsofordficialo Ulstér-Scotch)publicationoffiAgencycial publication(BoordoffiocialUlstér-Scotch)publicationSATURDSAofAYfiTURDcialJANUpublicationAYARJAY SA20NUTURDAR2018Y 20AY 2018JANUSAARTURDY 20AY 2018JAsaturday,NUARY 20 novem2018 Ber 21, 2020 BPAag!GE – see16PA PageGE 1616 PAGE PA16GE 16 WIN...A FAMILY PASS TO W5! Ulster-Scots Agency (Boord o Ulstér-Scotch) official publication SATURDAY JANUARY 20 2018 PAGE 16 BuBurnsBurnsrnsAllBuBuNiNi SetrnsrnsghNigh fortghNitgu guLeidghghtarguartt anguguWeekaranartearanteanedan Twaedteteteededed totohitohithitaltotoaltlhihilalthethettlaltheriglrigthethehtrightrigrignohtnohthttenotenonosstetetesss xxxxxx xxxxxx xxxxxx xxxxxx xxxxxx Cllr Jim montgomery, mayor of antrim and newtownabbey, Cllr noreen mcClelland, deputy mayor of antrim and newtownabbey annonuce leidPhil weekCunningham twa with ian Crozier,and Aly Bain will Chief executive of the ulster-scots agency PhilfrontCunninghamthis year’sandBurnsAlyWeBainek willconcert frontin thethisWayear’terfronts BurHall,ns Wewithek concerplentytof inevtheentsWasetterfrontfor acrossHall, withthe Proplentyvince.of evFullentscosetveragefor acrosson pagesthe 8,Pro9vince.and 10 Phil CunninghamPhil CunninghamandPhilAlyCunninghamandBainFullAlycowillverageBainandwillonAlypagesBain8, 9willand 10 front thisfrontyear’thiss Buryear’frontnss -

Gibraltar: the Rock with Its Own Symbols

Gibraltar: The Rock with its own Symbols Roman Klimeš Abstract Gibraltar, a British Overseas Territory, is presented by means of geographic data and an historic overview. The history of the symbols of this territory began in 1502 when Spanish monarchs King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella granted the coat of arms of Gibraltar. Further development of the coat of arms is then described until the present day. The first flag used in Gibraltar, in 1870, was the colonial flag of the Government. Other flags from later periods are described down to the present. Other symbols used in Gibraltar, such as police emblem and flags of the Royal Gibraltar Yacht Club, are also described. There is also further demonstration of the use of various symbols in practice, such as on coins, banknotes, and stamps, and in houses, gardens, and public places. The Arms of Gibraltar Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 669 GIBRALTAR: THE ROCK WITH ITS OWN SYMBOLS GEOGRAPHIC AND HISTORIC OVERVIEW Since 2007 Gibraltar has held the status of a British overseas territory. (Figure 1) It is under the sovereignty of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, although this sovereignty has never been recognized by Spain. Gibraltar is a small, narrow peninsula located at the southern edge of Spain, on the north side of the Strait of Gibraltar, where Europe and Africa are closest. The territory covers a land area of 6.8 square kilometres and has a population of approximately 30,000.