2106 Presbyterian Exiles Layout 1 15/05/2018 08:56 Page I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.1 Employment Sectors

1.1 EMPLOYMENT SECTORS To realise the economic potential of the Gateway and identified strategic employment centres, the RPGs indicates that sectoral strengths need be developed and promoted. In this regard, a number of thematic development areas have been identified, the core of which are pivoted around the main growth settlements. Food, Tourism, Services, Manufacturing and Agriculture appear as the primary sectors being proffered for Meath noting that Life Sciences, ICT and Services are proffered along the M4 corridor to the south and Aviation and Logistics to the M1 Corridor to the east. However, Ireland’s top 2 exports in 2010, medical and pharmaceutical products and organic chemicals, accounted for 59% of merchandise exports by commodity group. It is considered, for example, that Navan should be promoted for medical products noting the success of Welch Allyn in particular. An analysis has been carried out by the Planning Department which examined the individual employment sectors which are presently in the county and identified certain sectoral convergences (Appendix A). This basis of this analysis was the 2011 commercial rates levied against individual premises (top 120 rated commercial premises). The analysis excluded hotels, retail, public utilities public administration (Meath County Council, OPW Trim and other decentralized Government Departments) along with the HSE NE, which includes Navan Hospital. The findings of this analysis were as follows: • Financial Services – Navan & Drogheda (essentially IDA Business Parks & Southgate Centre). • Industrial Offices / Call Centres / Headquarters – Navan, Bracetown (Clonee) & Duleek. • Food and Meath Processing – Navan, Clonee and various rural locations throughout county. • Manufacturing – Oldcastle and Kells would have a particular concentrations noting that a number of those with addresses in Oldcastle are in the surrounding rural area. -

APRIL 2020 I Was Hungry and You Gave Me Something to Eat Matthew 25:35

APRIL 2020 I was hungry and you gave me something to eat Matthew 25:35 Barnabas stands alongside our Christian brothers and sisters around the world where they suffer discrimination and persecution. By providing aid through our Christian partners on the ground, we are able to maintain our overheads at less than 12% of our income. Please help us to help those who desperately need relief from their suffering. Barnabas Fund Donate online at: is a company Office 113, Russell Business Centre, registered in England 40-42 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 6AA www.barnabasaid.org/herald Number 04029536. Registered Charity [email protected] call: 07875 539003 Number 1092935 CONTENTS | APRIL 2020 FEATURES 12 Shaping young leaders The PCI Intern Scheme 16 Clubbing together A story from Bray Presbyterian 18 He is risen An Easter reflection 20 A steep learning curve A story from PCI’s Leaders in Training scheme 22 A shocking home truth New resource on tackling homelessness 34 Strengthening your pastoral core Advice for elders on Bible use 36 Equipping young people as everyday disciples A shocking home truth p22 Prioritising discipleship for young people 38 A San Francisco story Interview with a Presbyterian minister in California 40 Debating the persecution of Christians Report on House of Commons discussion REGULARS A San Francisco story p38 Debating the persecution of Christians p40 4 Letters 6 General news CONTRIBUTORS 8 In this month… Suzanne Hamilton is Tom Finnegan is the Senior Communications Training Development 9 My story Assistant for the Herald. Officer for PCI. In this role 11 Talking points She attends Ballyholme Tom develops and delivers Presbyterian in Bangor, training and resources for 14 Life lessons is married to Steven and congregational life and 15 Andrew Conway mum to twin boys. -

58 Farr James Wood

JAMES WOOD EAST DOWN’S LIBERAL MP 4 Journal of Liberal History 58 Spring 2008 JAMES WOOD EAST DOWN’S LIBERAL MP ‘I thought you might he object of our inter- its expression of praise of James est was a thick leather- Wood and the political stand he be interested in this,’ bound book covered took. was the understatement in embossed decora- It reads: from George Whyte tion and measuring Ttwelve inches by fourteen inches Dear Sir of Crossgar, who had in size. The title page, in richly- After your contest at the decorated lettering of gold, red late General Election to remain come across something and green, interwoven with flax Liberal Representative of East of fascinating flowers, read, ‘Address and Pres- Down in the Imperial Parlia- entation to James Wood, Esq., ment, your supporters in that local interest at a Member of Parliament for East Division, and numerous friends Belfast auction. Down, 1902–06 from His Late elsewhere, are anxious to Constituents.’ Another page express to you in tangible form Auctions provide contained a sepia photograph of their admiration for the gen- much television a serious-looking James Wood tlemanly manner in which you in a high collar and cravat, sur- conducted your part of the con- entertainment, but they rounded by a decorated motif tests in the interests of Reform, can also be a valuable of shamrock, flax, roses and Sobriety, Equal Rights and thistles.1 Goodwill among men – as source of local history, In Victorian and Edward- against the successful calumny, ian times, illuminated addresses intemperance, and organised and this find was to were a popular way of expressing violence of your opponents shed new light on an esteem for a person, particularly who have always sought to as a form of recognition for pub- maintain their own private episode in Irish history lic service. -

Health Falls Ward HB26/33/004 St, Comgall’S Primary School, Divis Street, Belfast, Co

THE BELFAST GAZETTE FRIDAY 25 JANUARY 2002 65 The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) Order 1991. Order 1991. District of Larne District of Larne Ballycarry Ward Ballycarry Ward HB06/05/013F HB06/05/049 Garden Turret at Red Hall, Ballycarry, Larne, Co. Antrim. 54 Main Street, Ballycarry, Carrickfergus, Co. Antrim, BT38 9HH. The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) Order 1991. Order 1991. District of Larne District of Larne Ballycarry Ward Ballycarry Ward HB06/05/013E HB06/05/036 Garden Piers at Red Hall, Ballycarry, Larne, Co. Antrim. Lime kilns at 9 Ballywillin Road, Glenoe, Larne, Co. Antrim. The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on 19th Historic Monuments December 2001, it prepared a list of buildings of special architectural or historic interest under Article 42 of the Planning (Northern Ireland) The Department of the Environment hereby gives notice that on the Order 1991. -

Magherintemple Gate Lodge

Magherintemple Lodge Sleeps 2 adults and 2 chlidren – Ballycastle, Co Antrim Situation: Presentation: 1 dog allowed. Magherintemple Lodge is located in the beautiful seaside town of Ballycastle on the north Antrim Coast. It is a wonderful get-away for the family. There is a great feeling of quiet and peace, yet it is only 5 mins drive to the beach. The very spacious dining and kitchen room is full of light. The living room is very comfortable and on cooler evenings you can enjoy the warmth of a real log fire. Hidden away at the top of the house is a quiet space where you can sit and read a book, or just gaze out the window as you relax and enjoy the peace and quiet which surrounds you. 1 chien admis. La loge de Magherintemple est située dans la ville balnéaire de Ballycastle sur la côte nord d'Antrim. Elle permet une merveilleuse escapade pour toute la famille. Il s’en dégage un grand sentiment de calme et de paix et est à seulement 5 minutes en voiture de la plage. La salle à manger est très spacieuse et la cuisine est très lumineuse. Le salon est très confortable et les soirées fraîches, vous pouvez profiter de la chaleur d'un vrai feu de bois. Caché dans la partie supérieure de la maison, un espace tranquille où vous pouvez vous asseoir et lire un livre, ou tout simplement regarder par la fenêtre, pour vous détendre et profiter de la paix et du calme qui vous entoure. History: This is a beautiful gatelodge situated just outside the town of Ballycastle. -

Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report Local Development Plan 2030 - Draft Plan Strategy

Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report Local Development Plan 2030 - Draft Plan Strategy Have your say Mid and East Antrim Borough Council is consulting on the Mid and East Antrim Local Development Plan - Draft Plan Strategy 2030. Formal Consultation The draft Plan Strategy will be open for formal public consultation for a period of eight weeks, commencing on 16 October 2019 and closing at 5pm on 11 December 2019. Please note that representations received after the closing date on 11 December will not be considered. The draft Plan Strategy is published along with a range of assessments which are also open for public consultation over this period. These include a Sustainability Appraisal (incorporating a Strategic Environmental Assessment), a draft Habitats Regulations Assessment, a draft Equality (Section 75) Screening Report and a Rural Needs Impact Assessment. We welcome comments on the proposals and policies within our draft Plan Strategy from everyone with an interest in Mid and East Antrim and its continuing development over the Plan period to 2030. This includes individuals and families who live or work in our Borough. It is also important that we hear from a wide spectrum of stakeholder groups who have particular interests in Mid and East Antrim. Accordingly, while acknowledging that the list below is not exhaustive, we welcome the engagement of the following groups: . Voluntary groups . Business groups . Residents groups . Developers/landowners . Community forums and groups . Professional bodies . Environmental groups . Academic institutions Availability of the Draft Plan Strategy A copy of the draft Plan Strategy and all supporting documentation, including the Sustainability Appraisal Report, is available on the Mid and East Antrim Borough Council website: www.midandeastantrim.gov.uk/LDP The draft Plan Strategy and supporting documentation is also available in hard copy or to view during office hours, 9.30am - 4.30pm at the following Council offices: . -

ADAIR MANOR Ballymoney Road • Ballymena CONTEMPORARY HOMES for MODERN LIVING

CONTEMPORARY HOMES FOR MODERN LIVING ADAIR MANOR Ballymoney Road • Ballymena CONTEMPORARY HOMES FOR MODERN LIVING ADAIR MANOR Ballymoney Road • Ballymena ADAIR MANOR Adair Manor is a small exclusive new development of contemporary homes and apartments, situated just off the highly sought after Ballymoney Road, Ballymena. This unique new development will certainly appeal to purchasers who recognise quality and workmanship. With a superb range of modern semi detached homes, townhouses and apartments, all cleverly incorporated in a Fairhill Shopping Centre delightfully planned site layout, this landmark development offers a superb specification and introduces a whole new choice of stylish living to this part of the town. The local area boasts several excellent golf courses including Galgorm Castle and Ballymena Golf Club, rugby, football, Ballymena Bowling Club hockey and a bowling club plus the superb facilities at The Peoples Park and riverside walsk along the Braid. There are a number of excellent primary schools, nurseries, and grammar schools in Ballymena, some of which are within an easy walk, and the ideal location close to the town centre ensures that residents could not be better situated to enjoy all the superb The Braid Galgorm Castle Golf Club facilities that this wonderful historic town has to offer. The developers and architect have invested much time and effort into designing homes which are both functional and aesthetically pleasing. Combine this with living spaces which meet the needs of modern lifestyles and you get homes which are modern, both inside and outside.The craftsmanship, thought and attention to detail that has gone in to these homes will make them notable for their style and external finish, enhancing the beautiful ambience of the area, and providing a development that will maintain its appeal for decades. -

Local Council 2019 Polling Station Scheme

LOCAL COUNCIL 2019 POLLING STATION SCHEME LOCAL COUNCIL: NEWRY, MOURNE AND DOWN DEA: CROTLIEVE POLLING STATION: ROSTREVOR PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH HALL, WARRENPOINT RD, ROSTREVOR, BT34 3EB BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE 987 WARD STREET POSTCODE N08001035BRIDGE STREET, ROSTREVOR BT34 3BG N08001035CARRICKBAWN PARK, ROSTREVOR BT34 3AP N08001035ST. BRONACHS COTTAGES, ROSTREVOR BT34 3DF N08001035CHERRY HILL, ROSTREVOR BT34 3BD N08001035CHURCH STREET, ROSTREVOR BT34 3BA N08001035ST BRONAGHS COURT, ROSTREVOR BT34 3DY N08001035CLOUGHMORE PARK, ROSTREVOR BT34 3AX N08001035CLOUGHMORE ROAD, ROSTREVOR BT34 3EL N08001035FORESTBROOK PARK, ROSTREVOR BT34 3DX N08001035FORESTBROOK AVENUE, ROSTREVOR BT34 3BX N08001035FORESTBROOK ROAD, NEWTOWN BT34 3BT N08001035SHANWILLAN, ROSTREVOR BT34 3GH N08001035GLEANN RUAIRI, ROSTREVOR BT34 3GE N08001035GLEANN SI, ROSTREVOR BT34 3TX N08001035GLENVIEW TERRACE, ROSTREVOR BT34 3ES N08001035GREENPARK ROAD, ROSTREVOR BT34 3EY N08001035KILBRONEY COURT, ROSTREVOR BT34 3EX N08001035GREENDALE CRESCENT, ROSTREVOR BT34 3HF N08001035GREENPARK COURT, ROSTREVOR BT34 3GS N08001035BRICK ROW, ROSTREVOR BT34 3BQ N08001035GLENMISKAN, ROSTREVOR BT34 3FF N08001035HORNERS LANE, ROSTREVOR BT34 3EJ N08001035KILBRONEY ROAD, ROSTREVOR BT34 3BH N08001035KILBRONEY ROAD, ROSTREVOR BT34 3HU N08001035KILLOWEN TERRACE, ROSTREVOR BT34 3ER N08001035MARY STREET, ROSTREVOR BT34 3AY N08001035NEWTOWN ROAD, ROSTREVOR BT34 3DD N08001035NEWTOWN ROAD, ROSTREVOR BT34 3BY N08001035NEWTOWN ROAD, ROSTREVOR BT34 3BY N08001035NEWTOWN ROAD, ROSTREVOR BT34 3BZ N08001035PINEWOOD, -

Age Friendly Ireland 51

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Contents Foreword 1 Highlights 2020 2 Corporate Services 4 Housing 17 Planning and Development 22 Heritage 22 Road Transportation and Safety 26 Environment, Fire and Emergency Services 33 Community 42 Age Friendly Ireland 51 Library Services 55 Arts Office 58 Economic Development and Enterprise 64 Tourism 66 Water Services 70 Finance 72 Human Resources 74 Information Systems 78 Appendix 1 – Elected Members Meath County Council 80 Appendix 2 – Strategic Policy Committee (SPC) Members 81 Appendix 3 – SPC Activities 83 Appendix 4 – Other Committees of the Council 84 Appendix 5 – Payments to Members of Meath County Council 89 Appendix 6 – Conferences Abroad 90 Appendix 7 - Conferences/Training at Home 91 Appendix 8 – Meetings of the Council – 2020 93 Appendix 9 – Annual Financial Statement 94 Appendix 10 – Municipal District Allocation 2020 95 Appendix 11 – Energy Efficiency Statement 2019 98 This Annual Report has been prepared in accordance with Section 221 of the Local Government Act and adopted by the members of Meath County Council on June 14, 2021. Meath County Council Annual Report 2020 Foreword We are pleased to present Meath County Council’s Annual Report 2020, which outlines the achievements and activities of the Council during the year. It was a year dominated by the COVID pandemic, which had a significant impact on the Council’s operating environment and on the operations of the Council and the services it delivers. Despite it being a year like no other, the Council continued to deliver essential and frontline local services and fulfil its various statutory obligations, even during the most severe of the public health restrictions. -

Heart of the Glens Landscape Partnership Industrial Heritage Audit

Heart of the Glens Landscape Partnership Industrial Heritage Audit March 2013 Contents 1. Background to the report 3 2. Methodology for the research 5 3. What is the Industrial Heritage of the Antrim Coast and Glens? 9 4. Why is it important? 11 5. How is it managed and conserved today? 13 6. How do people get involved and learn about the heritage now? 15 7. What opportunities are there to improve conservation, learning and participation? 21 8. Project Proposals 8.1 Antrim Coast Road driving route mobile app 30 8.2 Ore Mining in the Glens walking trail mobile app 35 8.3 Murlough Bay to Ballycastle Bay walking trail mobile app 41 8.4 MacDonnell Trail 45 8.5 Community Archaeology 49 8.6 Learning Resources for Schools 56 8.7 Supporting Community Initiatives 59 Appendices A References 67 B Gazetteer of industrial sites related to the project proposals 69 C Causeway Coast and Glens mobile app 92 D ‘History Space’ by Big Motive 95 E Glenarm Regeneration Plans 96 F Ecosal Atlantis Project 100 2 1. Background to the report This Industrial Heritage Audit has been commissioned by the Causeway Coast and Glens Heritage Trust (CCGHT) as part of the development phase of the Heart of the Glens Landscape Partnership Scheme. The Causeway Coast and Glens Heritage Trust is grateful for funding support by the Heritage Lottery Fund for Northern Ireland and the NGO Challenge Fund to deliver this project. CCGHT is a partnership organisation involving public, private and voluntary sector representatives from six local authorities, the community sector, and the environment sector together with representatives from the farming and tourism industries. -

Transcription of Ruth Mcfetridge's Death Book Sorted A

RUTH MCFETRIDGE'S DEATH BOOK Transcribed by Anne Shier Klintworth LAST NAME FIRST NAME RESIDENCE DATE OF DEATH NOTES ADAIR HARRY ESKYLANE 30-Jun-1979 ADAIR HETTIE (SCOTT) BELFAST ROAD, ANTRIM 30-Sep-1991 ADAIR INA ESKYLANE 23-Aug-1980 SAM MILLAR'S SISTER ADAIR JOSEPH TIRGRACEY, MUCKAMORE 31-Dec-1973 ADAIR WILLIAM TIRGRACEY, MUCKAMORE 18-Jan-1963 ADAMS CISSY GLARRYFORD 18-Feb-1999 WILLIAM'S HALF UNCLE (I BELIEVE SHE IS REFERING TO HER HUSBAND WILLIAM ADAMS DAVID BALLYREAGH 8-Sep-1950 MCFETRIDGE ADAMS DAVID LISLABIN 15-Sep-1977 AGE 59 ADAMS DAVID RED BRAE, BALLYMENA 19-Nov-1978 THORBURN'S FATHER ADAMS ENA CLOUGHWATHER RD. 4-Sep-1999 ISSAC'S WIFE ADAMS ESSIE CARNCOUGH 18-Dec-1953 ISSAC'S MOTHER WILLIAM'S GRANDFATHER (I BELIEVE SHE IS REFERING TO HER HUSBAND WILLIAM ADAMS ISSAC BALLYREAGH 23-Oct-1901 MCFETRIDGE ADAMS ISSAC CLOUGHWATHER RD. 28-Nov-1980 ADAMS JAMES SMITHFIELD, BALLYMENA 21-Feb-1986 ADAMS JAMES SENIOR SMITHFIELD PLACE, BALLYMENA 7-Jun-1972 ADAMS JIM COREEN, BROUGHSHANE 20-Apr-1977 ADAMS JOHN BALLYREAGH 21-May-1969 ADAMS JOHN KILLYREE 7-Nov-1968 JEANIE'S FATHER ADAMS JOSEPH CARNCOUGH 22-Aug-1946 Age 54, ISSAC'S FATHER ADAMS MARJORIE COREEN, BROUGHSHANE 7-Aug-2000 ADAMS MARY AGNES MAY LATE OF SPRINGMOUNT ROAD, SUNBEAM, GLARRYFORD 29-Apr-2000 WILLIAM'S GRANDMOTHER (I BELIEVE SHE IS REFERING TO HER HUSBAND WILLIAM ADAMS MARY J. BALLYREAGH 28-Feb-1940 MCFETRIDGE ADAMS MRS. ADAM BALLYKEEL 28-Jul-1975 JOAN BROWN'S MOTHER ADAMS MRS. AGNES KILLYREE 16-Aug-1978 JEANIE'S MOTHER ADAMS MRS. -

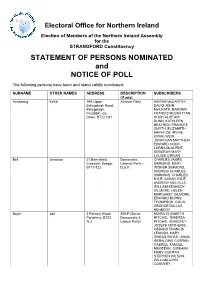

<Election Title>

Electoral Office for Northern Ireland Election of Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly for the STRANGFORD Constituency STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED and NOTICE OF POLL The following persons have been and stand validly nominated: SURNAME OTHER NAMES ADDRESS DESCRIPTION SUBSCRIBERS (if any) Armstrong Kellie 19A Upper Alliance Party KIERAN McCARTHY, Ballygelagh Road, DAVID JOHN Ballygelagh, McILRATH, EAMONN Kircubbin, Co. FRANCIS McGRATTAN, Down, BT22 1JH HUGH ALISTAIR DUNN, KATHLEEN BEATRICE FRANCES SMYTH, ELIZABETH MATHILDE IRVINE, CRAIG WEIR, JONATHAN MATTHEW EDWARD COOK, LORNA McALPINE, DEBORAH MARY LOUISE GIRVAN Bell Jonathan 21 Beechfield Democratic CHARLES JAMES Crescent, Bangor, Unionist Party - SIMMONS, MARY BT19 7ZJ D.U.P. WISNER SIMMONS, ANDREW CHARLES SIMMONS, CHARLES KYLE, SARAH KYLE, ANDREW MELVILLE, WILLIAM KENNEDY GILMORE, HELEN MARGARET GILMORE, EDWARD BURNS THOMPSON, COLIN GEORGE DALLAS KENNEDY Boyle Joe 3 Rectory Wood, SDLP (Social MOIRA ELIZABETH Portaferry, BT22 Democratic & RITCHIE, TERESSA 1LJ Labour Party) RITCHIE, BENEDICT JOSEPH MATHEWS, GERARD FRANCIS LENNON, MARY SINEAD BOYLE, ANNA GERALDINE CURRAN, GABRIEL SAMUEL MAGEEAN, SIOBHAN MARY CURRAN, STEPHEN WILSON, WILLIAM JOHN CONVERY Cooper Stephen 85 High Street, Traditional Unionist JOHN JAMES Comber, Co. Down, Voice - TUV COOPER, EILEEN BT23 5HJ COOPER, WILLIAM GEOFFREY DEMPSTER, PETER JOHN NOLAN, SAMUEL THOMAS HATRICK, IVAN LEONARD DEMPSTER, CHARLES WILLIAM GILL, DAVID MARK McMULLEN, CHRISTINE JANE GARRETT, JOHN SAMUEL ALLISTER Crosby Stephen (address in the UKIP DAVID MASON Sherwood McNARRY, ISABELLA Constituency) HANNA, JOHN McKNIGHT, ALEXANDRA ELIZABETH McNARRY, MARTHA MAUREEN SHARON CLELAND, SAMUEL ARTHUR CLELAND, WILLIAM ROBERT CONNOLLY, ELIZABETH MARY CONNOLLY, STANLEY MAXWELL HILES, JAMES DESMOND MILLIGAN Grainger Georgia 19 Glasswater Green Party JENNIFER ANNE Road, Crossgar, GRAINGER, EOIN Co.