Emigration to North Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo

A CLASS ACADEMY OF ENGLISH BELS GOZO EUROPEAN SCHOOL OF ENGLISH (ESE) INLINGUA SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES St. Catherine’s High School, Triq ta’ Doti, ESE Building, 60, Tigne Towers, Tigne Street, 11, Suffolk Road, Kercem, KCM 1721 Paceville Avenue, Sliema, SLM 3172 Mission Statement Pembroke, PBK 1901 Gozo St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Tel: (+356) 2010 2000 Tel: (+356) 2137 4588 Tel: (+356) 2156 4333 Tel: (+356) 2137 3789 Email: [email protected] The mission of the ELT Council is to foster development in the ELT profession and sector. Malta Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.inlinguamalta.com can boast that both its ELT profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being Web: www.aclassenglish.com Web: www.belsmalta.com Web: www.ese-edu.com practically the only language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school maintains a national quality standard. All this has resulted in rapid growth for INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH the sector. ACE ENGLISH MALTA BELS MALTA EXECUTIVE TRAINING LANGUAGE STUDIES Bay Street Complex, 550 West, St. Paul’s Street, INSTITUTE (ETI MALTA) Mattew Pulis Street, Level 4, St.George’s Bay, St. Paul’s Bay ESE Building, Sliema, SLM 3052 ELT Schools St. Julian’s, STJ 3311 Tel: (+356) 2755 5561 Paceville Avenue, Tel: (+356) 2132 0381 There are currently 37 licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo. Malta can boast that both its ELT Tel: (+356) 2713 5135 Email: [email protected] St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Email: [email protected] profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being the first and practically only Email: [email protected] Web: www.belsmalta.com Tel: (+356) 2379 6321 Web: www.ielsmalta.com language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school Web: www.aceenglishmalta.com Email: [email protected] maintains a national quality standard. -

Currency in Malta )

CURRENCY IN MALTA ) Joseph C. Sammut CENTRAL BANK OF MALTA 2001 CONTENTS List of Plates ........................ ......................... ......... ............................................ .... ... XllI List of Illustrated Documents ............ ,...................................................................... XVll Foreword .................................................................................................................. XIX } Preface...................................................................................................................... XXI Author's Introduction............................................................................................... XXllI I THE COINAGE OF MALTA The Earliest Coins found in Malta.................................................................... 1 Maltese Coins of the Roman Period................................................................. 2 Roman Coinage ................................................................................................ 5 Vandalic, Ostrogothic and Byzantine Coins ........... ............ ............ ............ ...... 7 Muslim Coinage ............................................................................................... 8 Medieval Currency ........................................................................................... 9 The Coinage of the Order of St John in Malta (1530-1798) ............................ 34 The Mint of the Order...................................................................................... -

Maltese Colonial Identity: Latin Mediterranean Or British Empire?

The British Colonial Experience 1800-1964 The Impact on Maltese Society Edited by Victor Mallia-Milanes 2?79G ~reva Publications Published under the auspices of The Free University: Institute of Cultural Anthropology! Sociology of Development Amsterdam 10 HENRY FRENDO Maltese Colonial Identity: Latin Mediterranean or British Empire? Influenced by history as much as by geography, identity changes, or develops, both as a cultural phenomenon and in relation to economic factors. Behaviouristic traits, of which one may not be conscious, assume a different reality in cross-cultural interaction and with the passing of time. The Maltese identity became, and is, more pronounced than that of other Mediterranean islanders from the Balearic to the Aegean. These latter spoke varieties of Spanish and Greek in much the same way as the inhabitants of the smaller islands of Pantalleria, Lampedusa, or Elba spoke Italian dialects and were absorbed by the neighbouring larger mainlands. The inhabitants of modern Malta, however, spoke a language derived from Arabic at the same time as they practised the Roman Catholic faith and were exposed, indeed subjected, to European iDfluences for six or seven centuries, without becoming integrated with their closest terra firma, Italy.l This was largely because of Malta's strategic location between southern Europe and North Mrica. An identifiable Maltese nationality was thus moulded by history, geography, and ethnic admixture - the Arabic of the Moors, corsairs, and slaves, together with accretions from several northern and southern European races - from Normans to Aragonese. Malta then passed under the Knights of St John, the French, and much more importantly, the British. -

Annual Report 2020

HERITAGE MALTA (HM) ANNUAL REPORT 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 5 Capital Works 6 Exhibitions and Events 19 Collections and Research 23 Conservation 54 Education, Publications and Outreach 64 Other Corporate 69 Visitor Statistics 75 Appendix 1 – Calendar of Events 88 Appendix 2 – Purchase of Modern and Contemporary Artworks 98 Appendix 3 – Acquisition of Natural History Specimens 100 Appendix 4 – Purchase of Items for Gozo Museum 105 Appendix 5 – Acquisition of Cultural Heritage Items 106 Foreword 2020 has been a memorable year. For all the wrong reasons, some might argue. And they could be right on several levels. However, the year that has tested the soundness and solidity of cultural heritage institutions worldwide, has also proved to be an eye-opener and a valuable teacher, highlighting a wealth of resourcefulness that we might have otherwise remained unaware of. The COVID-19 pandemic was a direct challenge to Heritage Malta’s mission of accessibility, forcing the agency first to close its doors entirely to the public and later to restrict admissions and opening hours. However, the agency was proactive and foresighted enough to be able to adapt to its new scenario. We found ourselves in a situation where cultural heritage had to visit the public, and not vice versa. We were able to achieve this thanks to our continuous investment in technology and digitisation, which enabled us to make our heritage accessible to the public virtually. In this way, we facilitated alternative access to our sites while also launching our online shop, making it possible for our clients to buy the products usually found at our retail outlets in sites and museums. -

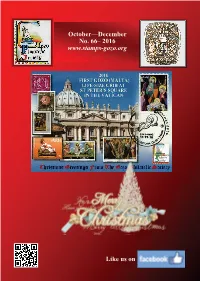

October—December No. 66– 2016 Like Us On

October—December No. 66– 2016 www.stamps-gozo.org Like us on GOZO PHILATELIC SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Founded on 3 September 1999 for the promotion of the hobby, the provision of a point of reference and co-ordination. 2 www.stamps-gozo.org October—December 2016 TO ALL MEMBERS PLEASE ENCOURAGE A FRIEND OR A RELATIVE TO JOIN OUR SOCIETY MEMBERSHIP PER ANNUM for local Senior Members €5.00 For overseas membership €15, including News Letter. (per annum) Fee for Junior membership under 16 years, is €2.00 per annum. 3 GOZO PHILATELIC SOCIETY NEWSLETTER GPS NEWSLETTER—Quarterly Organ of The Gozo Philatelic Society First issued on the 12th February 2000 — Editor: Austin Masini — Issue No. 66 (4/2016) Opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the Committee’s official policy. Correspondence (and material for publication) should be addressed to: The Editor, GPS, PO Box 10, VCT 1000, Gozo, Malta. © All rights reserved. Requests for reproduction of contents should be addressed to the Secretary. e-mail address: [email protected] CONTENTS. G.P.S Diary ............................................................................. Antoine Vassallo 5 The Perfins of Malta ................................................................ Peter C. Hansen 6 Gran Castello Redux .............................................................. Antoine Vassallo 14 Stamp Number 1...................................................................... Anthony Grech 16 GPS –Annual General Meeting .............................................. Louis Bonello 18 Our -

Malta TUNESIEN 0 200 Km TIPPS Mit REISE KNOW-HOW in Den Malta-Urlaub Starten: 42 Seiten Spezialkapitel Tauchen

Sardinien Werner Lips ITALIEN Handbuch für individuelles Entdecken Sizilien Gozo MITTEL- MEER Malta TUNESIEN 0 200 km TIPPS Mit REISE KNOW-HOW in den Malta-Urlaub starten: 42 Seiten Spezialkapitel Tauchen Malta, Gozo und Comino mit diesem kompletten Reiseführer entdecken: Die spektakulärsten Steilklippen: Malta Dingli Cliffs an der Südküste | 161 Z Sorgfältige Beschreibung aller sehenswerten Orte und Sehenswürdigkeiten | Z Unterkunftshinweise für jeden Geldbeutel: Mysteriöse steinzeitliche Nekropole: von der Ferienwohnung bis zum Luxus-Hotel das Hypogäum von Ħal Saflieni | 93 Z Transporthinweise vom Flugzeug über Helikopter, Der beste Aussichtspunkt: Kauderwelsch Fähre und Bus bis zum Karozzin Laferla Cross | 158 Fahrradführer Maltesisch – Z Tabelle der wichtigsten Busverbindungen Europa: Wort für Wort: Der schönste Badeplatz: Z der Reiseführer für der unkomplizierte Alle wichtigen Ortsnamen in Lautschrift Peter’s Pool auf der Delimara-Halbinsel | 127 Radler durch ganz Sprachführer, auch Z Malta-Glossar mit Kurzbiografien wichtiger Persönlichkeiten Europa für Anfänger Z Exkurse zu spannenden Hintergrundthemen Monumente älter als Stonehenge: die malerisch gelegenen Tempel von Ħaġar Qim und Mnajdra | 151 Z Die schönsten Wanderungen abseits der Hauptrouten Weitere Mittelmeer-Titel Malta, Gozo (1:50.000): Stätte der Schlacht aller Schlachten: (Auswahl): die detaillierte REISE KNOW-HOWVerlag Vittorosia, die alte Johanniter-Hauptstadt | 99 Z Istrien Landkarte Z 480 Seiten Peter Rump, Bielefeld Verlag Peter Rump Bielefeld Peter Verlag Wundersamer -

Malta Issofri, Ma Iccedix

360 4 Political Booklets in brown cover: Malta l-Ewwel u Qabel Kollox; Malta Issofri, Ma Iccedix; Il-Maltin u l-Inglizi; Xandira Ohra Ipprojbita; c.1950-1960 429 5 Volumes of the Proceedings of History week, 1993 - 2009; (5) 381 Abela A.E., Governors of Malta, 1991; Galea Michael, Malta: Historical Sketches, 1970; (2) 366 Abela A.E., Grace and Glory, 1997; Abela A.E., A Nation's Praise, 1994; (2) 275 Abela G.Francesco, Della Descrittione di Malta: Isola nel Mare Siciliano, 1647 26 Agius Muscat Hugo (editor), Buono Luciano (editor), Old Organs in Malta and Gozo: A Collection of Studies, 1998 385 Agreement on the Neutrality of Malta: Malta-USSR, 1981; The Extra Parliamentarians, 1982; Neutrality Agreement: Malta-Italy, 1980; Foreign Interferance in Malta, 1982; Ripe for Change, 1981; Karikaturi Politici, 1983; and 2 others; (8) 239 Alexander Joan, Mabel Strickland, 1996; Smith Harrison, Lord Strickland: Servant of the Crown, 1983; (2) 1 Antique Furniture in Malta, FPM 346 Aquilina George, Fiorini Stanley, The Origin of Franciscanism in Late Medieval Malta, 1995; Spiteri Charles B., Tifkiriet ta' l-Imghoddi, 1989; Said Godwin, Malta through Post Cards, 1989; (3) 147 Aquilina Gorg, Is-Sroijiet Gerosolimitani: Il-Knisja u l-Monasteru ta' Sant'Ursola Valletta, 2004 271 Athenaevm Melitense, 1926; Antonio Sciortino, 1947; (2) 326 Attard Anton F., Loghob Folkloristiku ta' Ghawdex, 1969 433 Attard Edward, Il-Habs: L-Istorja tal-Habsijiet f'Malta mil-1800, 2000; Attard Edward, Delitti f'Malta: 200 sena ta' Omicidji, 2004; (2) 221 Attard Joseph, Malta: -

Manwel Dimech: a Biography

MANWEL DIMECH: A BIOGRAPHY Manwel Dimech was born in Valletta on the Maltese population who accept without Christmas Day 1860. At his Christening he was demur whatever they were told without asking the named after the infant Jesus who was called why's and the wherefore's. In his view they were Emmanuele. like parrots. pastrydolls and ragballs. I His childhood does not appear to have been a Dimech attacked without respite the servile happy one. His father. an artisan. died when aspects in the Maltese national psychology with Emmanuele was still a boy. His mother was left regard to the sense of dependence on the govern without adequate means to ensure her children's ment. certain imports when many of these could education. have been manufactured locally and parochial Manwel took to the streets and when he was rivalries about local feasts and band clubs. Under not even seventeen years old, he was found guilty a colonial rule, Dimech was one who insisted on of complicity in a murder and sentenced to national unity, especially on the right and duty 20 years imprisonment. Soon after his release in of every citizen to interest himself actively in 1890, he was accused of dabbling in false coinage what was happening around him. and was again condemned to jail. In all he had to Dimech published two books on learning spend some twenty years of his life in prison. But languages : !1-Chel/iem Jngliz and !1-Che/liem tal instead of becoming a hardened criminal. as erbat ilsna. others are wont to do, he learned six languages. -

Remembering Manwel Dimech 99 Years After His Death

TIMES OF MALTA FRIDAY, APRIL 17,2020 f 11 ANNIVERSARY FEATURE Remembering Manwel Dimech 99 years after his death FR MARK MONTEBELLO rarely found and an excel lence seldom encountered. Prior to his exile in 1914, for A year short of a hundred 17 years, Dimech had almost years ago, on April 17, 1921, single-handedly championed a Sunday, Field Marshal in Malta the cause of the dis Viscount Edmund Allenby, possessed and the impover Britain's Spectal High Commis ished in order that they may sioner of Egypt and Com live in dignity and happiness. mander of the Egyptian He advocated Malta's inde Expeditionary Force, had little pendence more than 50 years time and care for petty news. before it was attained. His mind was elsewhere. A self-educated and a self He had a major riot on made man born in Valletta's his hands at Cairo. Though slums, Dimech paid the dear tempted to be rash and irrita price of the illiteracy, exclu ble, which never paid, he chose sion and poverty he was made instead, as he invariably did, to suffer by spending his youth the English blase, tarrying as if and early adulthood, some 20 unperturbed while sipping his years in all, behind bars. gin and tonic. During his public life, he The matter· was serious made two fatal mistakes which enough and partly his brought him ruin: he embold own doing. Saad Zaghloul, ened women to attain equal Egypt's one-time minister of rights in education and em education, minister of justice Manwel Dimech 1860-1921. -

Dominant Metaphor in Maltese Literature

Abstract This study deals with the way Malta has been represented in poetry and narrative written in Maltese. Metaphor, with its ability to stretch language and thought beyond its elastic limit, has played a fundamental role in the forging of the national imaginary that lies at the junction between real history and literary texts. On one hand, the conventional conceptual metaphors of the mother, home, traveller, and village are rooted in conventional conceptions of the nation; on the other, the relocation of the motherland in the sea marks a return to and a reinterpretation of the figure of the mother. While conventional conceptual metaphors have the potential to structure the concept of the nation by imagining the unimagined, fresh conceptual metaphors simultaneously create and defy that new structure. Dominant Metaphors in Maltese Literature DominantDominant MetaphorsMetaphors inin MalteseMaltese LiteratureLiterature Adrian Grima 2003 2 Dominant Metaphors in Maltese Literature This is an original study written by Adrian Grima 3 Dominant Metaphors in Maltese Literature 4 Dominant Metaphors in Maltese Literature DominantDominant MetaphorsMetaphors inin MalteseMaltese LiteratureLiterature A dissertation presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Malta for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Maltese Adrian Grima June, 2003 5 Dominant Metaphors in Maltese Literature A Note of Thanks I would like to thank my two supervisors, Professor Oliver Friggieri of the University of Malta and Professor Joseph A. Buttigieg of the University of Notre Dame (Indiana, USA) for their expert advice and encouragement throughout the six years that I have been working on this dissertation. I would also like to thank my colleagues at work, especially Mr. -

In Balluta by ������������������

ViGiLO - Din l-Art Ħelwa 28 Drawings & Descriptions in Balluta By homas MacGill wrote a book for visitors naval o$cers, merchants #ocked to the island to Malta in 1839, describing St Julian’s as seeking trade opportunities. ‘a favourite place’ which has ‘within but a In 1818 Aspinall took the bold step of Tfew years, become an extensive straggling village, marrying Marianna Galizia, aunt of the Maltese where several English families have villas’. architect Emmanuele Luigi Galizia (1830- Valletta was the centre of political and 1907). %e growing trend of ‘mixed marriages’ commercial life. Yet from the earliest days between Catholics and Anglicans was then of the British presence in Malta, those who the subject of considerable controversy in could a!ord it also sought houses with gardens Maltese Catholic society. %is cut both ways, outside the city, elsewhere on the island. One as Protestants also did not approve of marriage of the earliest popular ‘resorts’ among British with Catholics. residents was the bay of St Julian’s. At this Aspinall was an active and prominent period, St Julian’s was a small hamlet and member of society. He was appointed on the "shing village, within the parish of Birkirkara. "rst Council of Government in Malta in 1835, Among the residents of St Julian’s was remaining a member until the Council was Nicholas John Aspinall and his family, who dissolved in 1849. Following the completion lived at Spinola Palace in the 1830s and also of St Paul’s Anglican church in Valletta in had a house in Strada Mercanti in Valletta. -

Manwel Dimech Project

CALL FOR PERFORMERS MANWEL DIMECH PROJECT teatrumalta.org.mt We are currently working on a newly returned to his origins as a singer and song-writer, commissioned music theatre, site-specific collaborating with the Big Band Brothers in their production to commemorate the life and last album Xehda. work of Manwel Dimech (1860-1921) on the 100th anniversary of his death. This will be a Who is Kris Spiteri? multidisciplinary, audio-theatrical production, Kris Spiteri graduated in music studies from set to a variety of music genres, and performed the University of Malta. He co-wrote Porn, by an ensemble. the musical which won Best New Musical at the Off West End Theatre Awards and was This project is written and directed by Victor critic’s choice in Time Out London. He directed Jacono with Kris Spiteri as the composer and Hairspray, Fiddler on the Roof, My Fair Lady, the musical director. Mamma Mia, We Will Rock You and numerous pantomimes. In 2015 Kris joined Daniel Cauchi for the duo project Kafena, and they recorded Background information the album called Lukanda Propaganda with the Malta Philharmonic Orchestra. With his jazz Who is Victor Jacono? trio Noir, he recorded the album Till You Switch Dr. Victor-Emmanuel Jacono is a theatre-maker Off the Lights and performed it at the Malta and educator. He is coordinator for the Performing Jazz Festival. In collaboration with Immanuel Arts at the MCAST Institute for the Creative Mifsud, Vince Briffa and Teatru Anon, Kris wrote Arts, where he teaches acting and performance the music for Daqsxejn ta Requiem lil Leli, a production.