Rezensionen Für

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rezension Für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Rezension für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin Edition Friedrich Gulda – The early RIAS recordings Ludwig van Beethoven | Claude Debussy | Maurice Ravel | Frédéric Chopin | Sergei Prokofiev | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 4CD aud 21.404 Radio Stephansdom CD des Tages, 04.09.2009 ( - 2009.09.04) Aufnahmen, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Glasklar, "gespitzter Ton" und... Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Neue Musikzeitung 9/2009 (Andreas Kolb - 2009.09.01) Konzertprogramm im Wandel Konzertprogramm im Wandel Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Piano News September/Oktober 2009, 5/2009 (Carsten Dürer - 2009.09.01) Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 388 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton CD der Woche, 14.09.2009 (Wilfried Bestehorn, Oliver Schwesig - 2009.09.14) In einem Gemeinschaftsprojekt zwischen dem Label "audite" und Deutschlandradio Kultur werden seit Jahren einmalige Aufnahmen aus den RIAS-Archiven auf CD herausgebracht. Inzwischen sind bereits 40 CD's erschienen mit Aufnahmen von Furtwängler und Fricsay, von Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau u. v. a. Die jüngste Produktion dieser Reihe "The Early RIAS-Recordings" enthält bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Friedrich Gulda, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Die Einspielungen von Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel und Chopin zeigen den jungen Pianisten an der Schwelle zu internationalem Ruhm. Die Meinung unserer Musikkritiker: Eine repräsentative Auswahl bisher unveröffentlichter Aufnahmen, die aber bereits alle Namen enthält, die für Guldas späteres Repertoire bedeutend werden sollten: Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, Chopin. -

This Month's Highlights Release Date - Friday 30Th November 2018

DECEMBER 2018 DEALER INFORMATION SERVICE: NO. 323 THIS MONTH'S HIGHLIGHTS RELEASE DATE - FRIDAY 30TH NOVEMBER 2018 Download this month's information here: www.selectmusic.co.uk - USERNAME: dealer • PASSWORD: select All orders must be received a week prior to release date. Orders are shipped on the Wednesday preceding release date Please click on a label below to be directed to its relevant page. Thank you. CDs Accentus Music Hortus APR Kairos Arco Diva Melodiya BIS Orfeo Claudio Records Paladino Music Continuo Classics Profil CPO Prophone Dacapo Raumklang DB Productions Resonus Classics Delos Rondeau Production Divox Somm Recordings Doremi Sono Luminus Drama Musica Steinway & Sons Dynamic Toccata Classics Edition S Tudor Fondamenta Varese Sarabande Gramola Wergo DVDs Accentus Music Dynamic C Major Entertainment Vai Select Music and Video Distribution Limited Unit 8, Salbrook Industrial Estate, Salbrook Road, Salfords Redhill RH1 5GJ Tel: 01737 645600 • Fax: 01737 644065 • E: [email protected] • E: [email protected] • Twitter: @selectmusicuk Highlight of the Month Pascal Dusapin À quia; Aufgang; Wenn du dem Wind … Nicolas Hodges, Carolin Widmann, Natascha Petrinsky, Orchestre National des Pays de la Loire, Pascal Rophé BIS2262 £9.00 SACD 30/11/18 BIS About this Release Pascal Dusapin has composed a number of works for the stage, one of the more recent being the opera Penthesilea, after the play by Heinrich von Kleist. From the opera he has also fashioned Wenn Du dem Wind…, the concert suite which opens this disc. Although beginning and ending with a single line from a solo harp, throughout its course takes the listener through the extremes of love, war and the demands of inflexible laws. -

Divine Art Recordings Group Reviews Portfolio

PIANO SONATAS Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor, Op. 90 13:08 1 I. Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck 6:03 2 II. Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorzutragen 7:05 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) 3 Piano Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 12:57 Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Piano Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Op. 14 20:55 4 I. Allegro non troppo — più mosso — tempo primo 6:34 5 II. Scherzo: Allegro marcato 2:32 6 III. Andante 6:11 7 IV. Vivace — moderato — vivace 5:37 bonus tracks: Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Estampes 16:00 8 I. Pagodes 6:27 9 II. La soirée dans Grenade 5:18 10 III. Jardins sous la pluie 4:14 total playing time: 63:01 NATALIA ANDREEVA piano The Music I recorded these piano sonatas and “Estampes” at different stages of my life. It was a long journey: practicing, performing, teaching and doing the research… all helped me to create my own mental pictures and images of these piano masterpieces. Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor,Op. 90 “Why do I write? What I have in my heart must come out; and that is why I compose.” Those are famous words of the composer.1 There is a 4-5 year gap between Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 81a (completed in 1809) and Op. 90, composed in 1814. The Canadian pianist Anton Kuetri (who has recorded Beethoven’s complete Piano Sonatas) wrote: “For four years Beethoven wrote no sonatas, symphonies or string quartets. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2010 T 05 Stand: 19. Mai 2010 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin) 2010 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT05_2010-1 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie Katalogisierung, Regeln für Musikalien und Musikton-trä- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ger (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD -

2019 Book Catalog...(632KB)

Catalog of Recent Books About Music - Spring 2019 Books in Dutch: Hage, Jan. Muziek Als Missie : En Luthers Geluid In Een Calvinistische Wereld - Willem Mudde En De… $64.80 (Muziekhistorische Monografieen, Vol. 24) Utrecht: Vereniging V. Nederlandse ©2017 MM 24 9789063753986 Cloth; 25 cm.; 378 p. ...Kerkmuzikale Vernieuwingsbeweging. Mudde was an important voice in the church music renewal movement of the mid-20th century. This book examines his work , thought, and music. With an introduction, bibliography, and index. Summary in English. Black & white photos. http://www.tfront.com/p-458691-muziek-als-missie-en-luthers-geluid-in-een-calvinistische-wereld-willem-mudde-en-de….aspx Books in English: Arte Psallentes : John Nàdas : Studies In Music of The Tre- and Quattrocento. $127.50 (Studi E Saggi, Vol. 9) Lucca: Libreria Musicale Italiana ©2017 9788870969153 Paper; 26 cm.; xviii, 473 p. 14 articles on topics of late medieval and early renaissance music, in honor of the 70th birthday of the music scholar Nàdas. Includes color and black & white plates. http://www.tfront.com/p-449362-arte-psallentes-john-nàdas-studies-in-music-of-the-tre-and-quattrocento.aspx Bach and The Counterpoint of Religion / edited by Robin A. Leaver. $50.00 (Bach Perspectives, Vol. 12) Urbana, IL: Univ. Illinois Press ©2018 9780252041983 Cloth; 26 cm.; x, 157 p. Seven articles examine the influence of religions outside of Lutheranism on the music of Bach, including Catholicism and mysticism. With a preface and indices. http://www.tfront.com/p-468523-bach-and-the-counterpoint-of-religion-edited-by-robin-a-leaver.aspx Beatles, Sgt. -

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Live Moscow 1951 – 1963 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH 24 Preludes and Fugues for Piano, Op

SVIATOSLAV RICHTER EMIL GILELS TATJANA NIKOLAYEVA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH live Moscow 1951 – 1963 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH 24 Preludes and Fugues for Piano, Op. 87 1 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH 1906 – 1975 CD 2 Preludes and Fugues Nos. 11 – 20 BONUS CD 1 Tatjana Nikolayeva rec. Studio Moscow 1962 Sviatoslav Richter plays in Prague Studio December 3 – 4, 1956 Preludes and Fugues Nos. 1 – 10 BONUS 1. Prelude and Fugue No. 11 in B major 3'28 11. Prelude and Fugue No. 7 in A major 3'01 Emil Gilels, Studio Moscow 1955 Sviatoslav Richter plays live in Warsaw Sviatoslav Richter plays live in Teatr Muzyczny „Roma” November 24, 1954 1. Prelude and Fugue No. 1 in C major 7'05 Moscow March 14, 1963 Total time CD 2: 78'55 Four Preludes and Fugues – 2. Prelude and Fugue No. 12 in G sharp minor* 8'53 Sviatoslav Richter plays live in Moscow Suite of Sviatoslav Richter unpublished * November 9, 1956 11. Prelude and Fugue No. 4 in E minor* 7'56 Tatjana Nikolayeva rec. Studio Moscow 1962 2. Prelude and Fugue No. 2 in A minor 2'15 12. Prelude and Fugue No.7 in A major* 3'07 3. Prelude and Fugue No. 13 in F sharp major 9'36 3. Prelude and Fugue No. 3 in G major 3'33 13. Prelude and Fugue No.17 in A flat major* 5'22 Sviatoslav Richter plays live in Kiev June 9, 1963 Sviatoslav Richter plays live in 14. Prelude and Fugue No.12 in G sharp minor* 7'41 4. Prelude and Fugue No. -

SVIATOSLAV RICHTER Plays Rakhmaninov & Prokofiev 11 CD

Special Guests Mstislav Rostropovich Kurt Sanderling Kirill Kondrashin SVIATOSLAV RICHTER plays Rakhmaninov & Prokofiev 11 CD PH19052 St 1d, 19.11.2019 Bildquelle: verlag U1 Freigabe 16.9.19 Hänssler Farbunverbindlich. Keine Druckdaten. Bildrechte: vorhanden? Gesamt-Freigabe SPIESZDESIGN 20190903b Änderung gegenüber Vorentwurf: Korr 11 CD SVIATOSLAV RICHTER plays Rakhmaninov & Prokofiev CD 1 CD 2 CD 3 9 Etude Tableau No. 7 in C minor, Op. 39 – Sergei Rakhmaninov (1873 – 1943) Sergei Rakhmaninov (1873 – 1943) Sergei Rakhmaninov (1873 – 1943) Lento lugubre 6'23 23/06/1950 Moscow – live Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor, Op. 1 Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Op. 18 Eight Etudes-Tableaux Op. 33, Nos. 8, 4, 5 Op. 39, 10 „Melodie“ No. 3 E major Op. 3 vers. 1892 (Version 2/1917) 06/02/1959 Moscow – live* Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 9 (from Morceaux de Fantaisie)* 5'44 09/03/1949 Moscow – Studio (8 Etudes -Tableaux Suites of Sviatoslav Richter) 1 I Moderato 11'30 Adagio sostenuto 1 I Vivace – Moderato 12'11 2 II Adagio sostenuto 11'39 1 Etude Tableau No. 8 in C-sharp minor, Op. 33 – 10/01/1952 Moscow – live 2 II Andante cantabile 5'56 3 III Allegro scherzando 11'24 Grave* 3'00 11 „Liebesfreud“ – Paraphrase in C major of 3 III Allegro vivace 7'38 State Symphony Orchestra USSR Early 1950‘s Moscow – live Fritz Kreislers Valse „Love‘s Joy“* 5'49 Symphony Orchestra USSR Kurt Sanderling 2 Etudes Tableau No. 4 in D minor, Op.33 – 1947 Moscow – live Oleg Agarkov Moderato* 3'09 BONUS Early 1950‘s Moscow – live BONUS BONUS Piano Concerto No. -

Piano Sonatas

PIANO SONATAS Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor, Op. 90 13:08 1 I. Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck 6:03 2 II. Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorzutragen 7:05 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) 3 Piano Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 12:57 Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Piano Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Op. 14 20:55 4 I. Allegro non troppo — più mosso — tempo primo 6:34 5 II. Scherzo: Allegro marcato 2:32 6 III. Andante 6:11 7 IV. Vivace — moderato — vivace 5:37 bonus tracks: Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Estampes 16:00 8 I. Pagodes 6:27 9 II. La soirée dans Grenade 5:18 10 III. Jardins sous la pluie 4:14 total playing time: 63:01 NATALIA ANDREEVA piano The Music I recorded these piano sonatas and “Estampes” at different stages of my life. It was a long journey: practicing, performing, teaching and doing the research… all helped me to create my own mental pictures and images of these piano masterpieces. Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor, Op. 90 “Why do I write? What I have in my heart must come out; and that is why I compose.” Those are famous words of the composer.1 There is a 4-5 year gap between Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 81a (completed in 1809) and Op. 90, composed in 1814. The Canadian pianist Anton Kuetri (who has recorded Beethoven’s complete Piano Sonatas) wrote: “For four years Beethoven wrote no sonatas, symphonies or string quartets. -

Sonata for Violin and Piano (1952) 19:48 1 I

Galina Ustvolskaya (1919-2006) Complete works for Violin and Piano Sonata for Violin and Piano (1952) 19:48 1 I. (crotchet=112) 2:18 2 II. (crotchet=112) 9:36 3 III. Più mosso 2:25 4 IV. Tempo I 5:28 Duet for Violin and Piano (1964) 29:30 5 I. Espressivo 4:22 6 II. Very rhythmical beat (fugato) 5:47 7 III. Tempo I 2:54 8 IV. Not faster (fugato) 4:49 9 V. Meno mosso 1:20 10 VI. Tempo I 3:00 11 VII. (in tempo) 7:16 Total duration 49:19 Evgeny Sorkin violin | Natalia Andreeva piano The music Introduction and notes by Natalia Andreeva This recording is proudly dedicated to the memory of Galina Ustvolskaya on the 100th anniversary of her birth. “Ustvolskaya did paddle upstream, against one all-powerful current, and never once deviated from her course. That is why she is a Hero, not of, but against the Soviet Union. There was no less desirable music written in the imperium of Stalin and his successors than hers. And every subsequent piece was yet more undesirable, because it was more impossible and inaccessible than the previous one.”1 In 2006, in Chicago, I opened the score of Ustvolskaya’s Fifth Piano Sonata. This was the first of Ustvolskaya’s compositions that I ever started working on. I could not then imagine that it was a beginning of a very long journey: I read countless resources (I had the great advantage of reading both in English and Russian), practiced for hours and hours, performed Ustvolskaya’s works, held lecture-recitals, wrote my PhD thesis dedicated to Ustvolskaya’s piano works, and the list goes on. -

Divine Art Recordings Group Reviews Portfolio

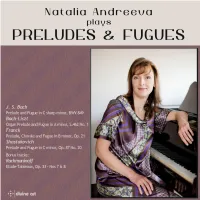

PRELUDES & FUGUES Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Prelude and Fugue in C sharp minor, BWV849 7:30 1 I. Prelude 2:56 2 II. Fugue 4:33 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) transcribed by Franz Liszt(1811-1886) Organ Prelude and Fugue in A minor, S. 462 No. 1 10:38 3 I. Prelude 3:42 4 II. Fugue 6:57 César Franck (1822-1890) Prélude, choral et fugue 21:32 5 I. Prélude 5:35 6 II. Choral 7:18 7 III. Fugue 8:39 Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Prelude and Fugue in C minor, Op. 87 No. 20 10:53 8 I. Prelude 4:50 9 II. Fugue 6:02 bonus tracks: Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) 10 Étude-Tableau in G minor, Op. 33 No. 7 3:41 11 Étude-Tableau in C sharp minor, Op. 33 No. 8 3:10 total playing time: 57:25 NATALIA ANDREEVA piano The Music This CD includes piano works — Preludes and Fugues and two of Rachmaninoff’s Étude-Tableaux — which were learned and performed at different stages of my life: in St. Petersburg (Russia), in Chicago and in Sydney. They were all recorded in the former Melodiya recording studio in St. Petersburg (located at the St. Catherine Lutheran Church) — the same studio where I recorded the complete piano works by the Russian composer Galina Ustvolskaya, released by Divine Art in 2015. Here, in these program notes, my aim is not to make an analysis of these piano works (so many great books have been written and much research has been done!). -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2017 T 05

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2017 T 05 Stand: 24. Mai 2017 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2017 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-201612065593 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie sche Katalogisierung von Ausgaben musikalischer Wer- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ke (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ zugrunde. -

Referenzen Our Customer’S File Is Headed by

References – Referenzen Our customer’s file is headed by ... unsere Kundenkartei wird angeführt von ... Franz Liszt und Richard Wagner, Joseph Rubinstein, Richard Strauss, Wilhelm Kempff, Engelbert Humperdinck, Cyprien Katsaris, Giuseppe Sinopoli, Daniel Barenboim, James Levine und Kit Armstrong Artists choose Steingraeber for concerts or recordings | Künstler wählen Steingraeber für Konzerte oder Aufnahmen Valery Afanassiev, Rieko Aizawa, Günter Albers, Lucia Aliberti, Sonsoles Alonso, Marcelo Amaral, Arthur Ancelle, Benny Andersson, Igor Androsov, Olga Andryushchenko, Leif Ove Andsnes, Kristina Annamuchamedova, Jean-François Antonioli, Rolf-Dieter Arens, Martha Argerich, Kit Armstrong, Sheila Arnold, Racha Arodaky, Suhrud Athavale, Yulianna Avdeeva, Abdel Rahman El Bacha, Farhad Badalbeyli, Paul Badura-Skoda, Steven Bailey, Susan Banoff, Klavierduo Barandiarán y Bustos, Daniel Barenboim, Tzimon Barto, Sandro Ivo Bartoli, Viktoria Baskakova, Christopher Basso, Mariam Batsashvili, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Tomislav Baynov, Markus Becker, Ludmila Berlinskaia, Philippe Bianconi, Fabio Bidini, Károly Binder, Malcom Bilson, Idil Biret, Boris Bloch, Lucas Blondeel, Elisaveta Blumina, Stefan Bojsten, Andrea Bonatta, Anne Le Bozec, Ronald Brautigam, Frank Braley, Alfred Brendel, Christopher Bruckman, Montserrat Caballé, Michele Campanella, Roberto Carnevale, Gianluca Cascioli, Boris Cepeda, Sa Chen, Maria Chershintseva, Frédéric Chiu, Ye-Eun Choi, Chia Chou, Ethella Chupryk, Francesco Cipolletta, Richard Clayderman, Benjamin Clementine, Emmet Cohen,