Galina Ustvolskaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis October 11,2012

Demystifying Galina Ustvolskaya: Critical Examination and Performance Interpretation. Elena Nalimova 10 October 2012 Submitted in partial requirement for the Degree of PhD in Performance Practice at the Goldsmiths College, University of London 1 Declaration The work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been presented for any other degree. Where the work of others has been utilised this has been indicated and the sources acknowledged. All the translations from Russian are my own, unless indicated otherwise. Elena Nalimova 10 October 2012 2 Note on transliteration and translation The transliteration used in the thesis and bibliography follow the Library of Congress system with a few exceptions such as: endings й, ий, ый are simplified to y; я and ю transliterated as ya/yu; е is е and ё is e; soft sign is '. All quotations from the interviews and Russian publications were translated by the author of the thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis presents a performer’s view of Galina Ustvolskaya and her music with the aim of demystifying her artistic persona. The author examines the creation of ‘Ustvolskaya Myth’ by critically analysing Soviet, Russian and Western literature sources, oral history on the subject and the composer’s personal recollections, and reveals paradoxes and parochial misunderstandings of Ustvolskaya’s personality and the origins of her music. Having examined all the available sources, the author argues that the ‘Ustvolskaya Myth’ was a self-made phenomenon that persisted due to insufficient knowledge on the subject. In support of the argument, the thesis offers a performer’s interpretation of Ustvolskaya as she is revealed in her music. -

Rezension Für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Rezension für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin Edition Friedrich Gulda – The early RIAS recordings Ludwig van Beethoven | Claude Debussy | Maurice Ravel | Frédéric Chopin | Sergei Prokofiev | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 4CD aud 21.404 Radio Stephansdom CD des Tages, 04.09.2009 ( - 2009.09.04) Aufnahmen, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Glasklar, "gespitzter Ton" und... Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Neue Musikzeitung 9/2009 (Andreas Kolb - 2009.09.01) Konzertprogramm im Wandel Konzertprogramm im Wandel Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Piano News September/Oktober 2009, 5/2009 (Carsten Dürer - 2009.09.01) Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 388 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton CD der Woche, 14.09.2009 (Wilfried Bestehorn, Oliver Schwesig - 2009.09.14) In einem Gemeinschaftsprojekt zwischen dem Label "audite" und Deutschlandradio Kultur werden seit Jahren einmalige Aufnahmen aus den RIAS-Archiven auf CD herausgebracht. Inzwischen sind bereits 40 CD's erschienen mit Aufnahmen von Furtwängler und Fricsay, von Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau u. v. a. Die jüngste Produktion dieser Reihe "The Early RIAS-Recordings" enthält bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Friedrich Gulda, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Die Einspielungen von Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel und Chopin zeigen den jungen Pianisten an der Schwelle zu internationalem Ruhm. Die Meinung unserer Musikkritiker: Eine repräsentative Auswahl bisher unveröffentlichter Aufnahmen, die aber bereits alle Namen enthält, die für Guldas späteres Repertoire bedeutend werden sollten: Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, Chopin. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Olympic Rowing Regatta Beijing, China 9-17 August

2008 Olympic Rowing Regatta Beijing, China 9-17 August MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTEnts 1. Introduction 3 2. FISA 5 2.1. What is FISA? 5 2.2. FISA contacts 6 3. Rowing at the Olympics 7 3.1. History 7 3.2. Olympic boat classes 7 3.3. How to Row 9 3.4. A Short Glossary of Rowing Terms 10 3.5. Key Rowing References 11 4. Olympic Rowing Regatta 2008 13 4.1. Olympic Qualified Boats 13 4.2. Olympic Competition Description 14 5. Athletes 16 5.1. Top 10 16 5.2. Olympic Profiles 18 6. Historical Results: Olympic Games 27 6.1. Olympic Games 1900-2004 27 7. Historical Results: World Rowing Championships 38 7.1. World Rowing Championships 2001-2003, 2005-2007 (current Olympic boat classes) 38 8. Historical Results: Rowing World Cup Results 2005-2008 44 8.1. Current Olympic boat classes 44 9. Statistics 54 9.1. Olympic Games 54 9.1.1. All Time NOC Medal Table 54 9.1.2. All Time Olympic Multi Medallists 55 9.1.3. All Time NOC Medal Table per event (current Olympic boat classes only) 58 9.2. World Rowing Championships 63 9.2.1. All Time NF Medal Table 63 9.2.2. All Time NF Medal Table per event 64 9.3. Rowing World Cup 2005-2008 70 9.3.1. Rowing World Cup Medal Tables per year 2005-2008 70 9.3.2. All Time Rowing World Cup Medal Tables per event 2005-2008 (current Olympic boat classes) 72 9.4. -

Rezensionen Für

Rezensionen für Edition Ferenc Fricsay (IV) – P. I. Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 2 & F. Liszt: Piano Concerto No. 1 aud 95.499 4022143954992 Audiophile Audition December 2008 (Gary Lemco - 2008.12.21) A truly happy discovery for the connoisseur, these inscriptions, one live (the... Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. CD Compact Marzo 2009 (Emili Blasco - 2009.03.01) Audite Edición Ferenc Fricsay Audite Edición Ferenc Fricsay Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Die Tonkunst Juli 2013 (Tobias Pfleger - 2013.07.01) Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a. Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a. Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 7 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de Fanfare Issue 32:5 (May/June 2009) (Lynn René Bayley - 2009.05.01) Pairing Romantic pianist Cherkassky and post-modern conductor Fricsay doesn’t even seem, on paper, like a good idea, let alone a recipe for success. As a pupil of Josef Hoffman and a representative of an older school that believed in impromptu changes to one’s performance approach, Cherkassky rode for 70 years on a wing and a prayer, while Fricsay came from the school of rehearse-exactly-as-you-play. Moreover, Cherkassky’s rhythmic and emotional freedom also seemed at odds with Fricsay’s insistence on written tempos and rhythms. The reason Deutsche Grammophon didn’t release the 1951 recording of the Tchaikovsky appears to be that someone at the label was disappointed by the sound of the orchestra. -

This Month's Highlights Release Date - Friday 30Th November 2018

DECEMBER 2018 DEALER INFORMATION SERVICE: NO. 323 THIS MONTH'S HIGHLIGHTS RELEASE DATE - FRIDAY 30TH NOVEMBER 2018 Download this month's information here: www.selectmusic.co.uk - USERNAME: dealer • PASSWORD: select All orders must be received a week prior to release date. Orders are shipped on the Wednesday preceding release date Please click on a label below to be directed to its relevant page. Thank you. CDs Accentus Music Hortus APR Kairos Arco Diva Melodiya BIS Orfeo Claudio Records Paladino Music Continuo Classics Profil CPO Prophone Dacapo Raumklang DB Productions Resonus Classics Delos Rondeau Production Divox Somm Recordings Doremi Sono Luminus Drama Musica Steinway & Sons Dynamic Toccata Classics Edition S Tudor Fondamenta Varese Sarabande Gramola Wergo DVDs Accentus Music Dynamic C Major Entertainment Vai Select Music and Video Distribution Limited Unit 8, Salbrook Industrial Estate, Salbrook Road, Salfords Redhill RH1 5GJ Tel: 01737 645600 • Fax: 01737 644065 • E: [email protected] • E: [email protected] • Twitter: @selectmusicuk Highlight of the Month Pascal Dusapin À quia; Aufgang; Wenn du dem Wind … Nicolas Hodges, Carolin Widmann, Natascha Petrinsky, Orchestre National des Pays de la Loire, Pascal Rophé BIS2262 £9.00 SACD 30/11/18 BIS About this Release Pascal Dusapin has composed a number of works for the stage, one of the more recent being the opera Penthesilea, after the play by Heinrich von Kleist. From the opera he has also fashioned Wenn Du dem Wind…, the concert suite which opens this disc. Although beginning and ending with a single line from a solo harp, throughout its course takes the listener through the extremes of love, war and the demands of inflexible laws. -

MUSICAL CENSORSHIP and REPRESSION in the UNION of SOVIET COMPOSERS: KHRENNIKOV PERIOD Zehra Ezgi KARA1, Jülide GÜNDÜZ

SAYI 17 BAHAR 2018 MUSICAL CENSORSHIP AND REPRESSION IN THE UNION OF SOVIET COMPOSERS: KHRENNIKOV PERIOD Zehra Ezgi KARA1, Jülide GÜNDÜZ Abstract In the beginning of 1930s, institutions like Association for Contemporary Music and the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians were closed down with the aim of gathering every study of music under one center, and under the control of the Communist Party. As a result, all the studies were realized within the two organizations of the Composers’ Union in Moscow and Leningrad in 1932, which later merged to form the Union of Soviet Composers in 1948. In 1948, composer Tikhon Khrennikov (1913-2007) was appointed as the frst president of the Union of Soviet Composers by Andrei Zhdanov and continued this post until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Being one of the most controversial fgures in the history of Soviet music, Khrennikov became the third authority after Stalin and Zhdanov in deciding whether a composer or an artwork should be censored or supported by the state. Khrennikov’s main job was to ensure the application of socialist realism, the only accepted doctrine by the state, on the feld of music, and to eliminate all composers and works that fell out of this context. According to the doctrine of socialist realism, music should formalize the Soviet nationalist values and serve the ideals of the Communist Party. Soviet composers should write works with folk music elements which would easily be appreciated by the public, prefer classical orchestration, and avoid atonality, complex rhythmic and harmonic structures. In this period, composers, performers or works that lacked socialist realist values were regarded as formalist. -

Gubaidulina EU 572772 Bk Gubaidulina EU 26/07/2011 07:59 Page 1

572772 bk Gubaidulina EU_572772 bk Gubaidulina EU 26/07/2011 07:59 Page 1 Anders Loguin Øyvind Gimse Anders Loguin studied percussion at the Royal Øyvind Gimse is Artistic Leader of the Trondheim Soloists and a distinguished College of Music in Stockholm, and conducting in cellist and orchestral leader. After studies with Walter Nothas, Frans Helmerson Sweden, Finland and the United States. He and William Pleeth, he held the position of solo cellist in the Trondheim Sofia frequently conducts orchestras and ensembles in Symphony Orchestra for seven years. He has toured as a soloist with the Sweden and abroad. He was a founding member of Trondheim Soloists in Norway, Britain, Italy and Spain. His performances with the percussion ensemble Kroumata, and left the Anne-Sophie Mutter and the Trondheim Soloists throughout Europe and at the ensemble in 2008, co-founding the Carnegie Hall in 1999, as well as the recordings with her and the ensemble for GUBAIDULINA ensemble Glorious Percussion, which gave the DG, have received the highest critical acclaim. In addition his own work as world première of Sofia Gubaidulina’s work of the Artistic Leader of the Trondheim Soloists has resulted in the group receiving no same name for five percussionists and less than five GRAMMY® nominations for their last two recordings. In 2004 orchestra. Loguin participated in the world Gimse joined Sofia Gubaidulina as soloist in her work On the Edge of the première concerts of Fachwerk in 2009. Since 1977 Abyss at the Trondheim Chamber Music Festival and during the world Photo: Brita Carlens he has been professor and head of the percussion première concert performances of Fachwerk with Geir Draugsvoll and the department at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm. -

Masculinity Versus Femininity: an Overriding Dichotomy in the Music of Soviet Composer Galina Ustvolskaya

eSharp Issue 9 Gender: Power and Authority Masculinity Versus Femininity: An Overriding Dichotomy in the Music of Soviet Composer Galina Ustvolskaya Rachel Foulds (Goldsmiths College, University of London) The issue and explanation of the shortage of female composers in the musical canon has been relentlessly stated since the latter part of the twentieth century. As many of these writings have been by female musicians themselves, perhaps the search for an explanation has often been personal at the sacrifice of the professional. Despite the change of social circumstance in Western Europe since the nineteenth century, little has been done to encourage the contribution of female musicians to such a male-dominated music culture; the music world has long since been regarded as ‘masculine’. There have been many reasons suggested to explain a lack of female composers in this occupational field: Jill Halstead devotes a chapter in her book ‘The Woman Composer’ (1996, pp.3-31) to obliterating the myth of biological difference as the major factor of the disparity of male and female achievement in this discipline. Numerous scholars, including Halstead, have continued to explore gender issues including the question of what affects women’s ingenuity, creativity and equal partaking in music culture. Of course, sociological restrictions were imposed upon women for centuries, yet Ustvolskaya’s life as a woman and her expected role within the Soviet regime differed enormously from women in the rest of the world. Despite an apparent recent trend for these gender studies, much opposition, criticism and skepticism is evoked by such research, not least by Ustvolskaya. -

Divine Art Recordings Group Reviews Portfolio

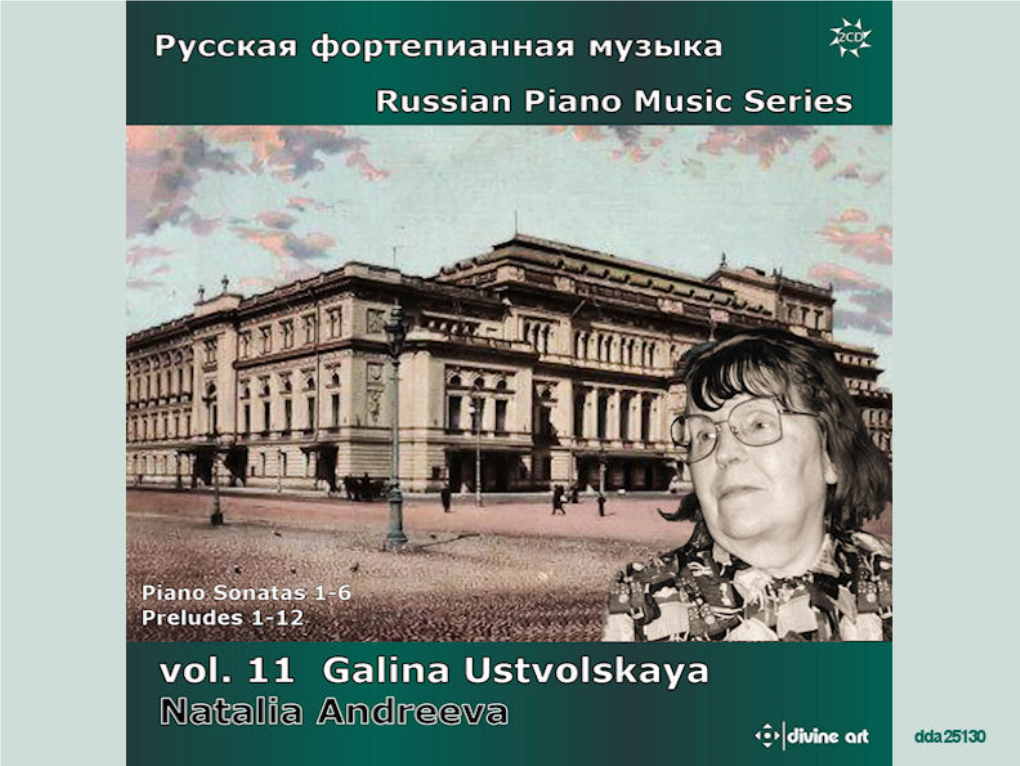

PIANO SONATAS Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor, Op. 90 13:08 1 I. Mit Lebhaftigkeit und durchaus mit Empfindung und Ausdruck 6:03 2 II. Nicht zu geschwind und sehr singbar vorzutragen 7:05 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) 3 Piano Sonata No. 10, Op. 70 12:57 Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) Piano Sonata No. 2 in D minor, Op. 14 20:55 4 I. Allegro non troppo — più mosso — tempo primo 6:34 5 II. Scherzo: Allegro marcato 2:32 6 III. Andante 6:11 7 IV. Vivace — moderato — vivace 5:37 bonus tracks: Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Estampes 16:00 8 I. Pagodes 6:27 9 II. La soirée dans Grenade 5:18 10 III. Jardins sous la pluie 4:14 total playing time: 63:01 NATALIA ANDREEVA piano The Music I recorded these piano sonatas and “Estampes” at different stages of my life. It was a long journey: practicing, performing, teaching and doing the research… all helped me to create my own mental pictures and images of these piano masterpieces. Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 27 in E minor,Op. 90 “Why do I write? What I have in my heart must come out; and that is why I compose.” Those are famous words of the composer.1 There is a 4-5 year gap between Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 81a (completed in 1809) and Op. 90, composed in 1814. The Canadian pianist Anton Kuetri (who has recorded Beethoven’s complete Piano Sonatas) wrote: “For four years Beethoven wrote no sonatas, symphonies or string quartets. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2010 T 05 Stand: 19. Mai 2010 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin) 2010 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT05_2010-1 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie Katalogisierung, Regeln für Musikalien und Musikton-trä- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ger (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD -

Musical Contents and Symbolic Interpretation in Sofia Gubaidulina’S “Two Paths: a Dedication to Mary and Martha”

MUSICAL CONTENTS AND SYMBOLIC INTERPRETATION IN SOFIA GUBAIDULINA’S “TWO PATHS: A DEDICATION TO MARY AND MARTHA” DMA DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Young-Mi Lee, M.Ed. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Document Committee: Approved by Professor Jan Radzynski, Adviser Professor Donald Harris Professor Margarita Mazo Adviser Music Graduate Program ABSTRACT Sofia Gubaidulina has been known for using symbolic devices in her music to express her Christian belief. Two paths: A Dedication to Mary and Martha for two violas and orchestra (1998) effectively represents Gubaidulina’s musical aesthetic which is based on the idea of dichotomy. In the wide stretch over various genres, many pieces reflect her dual worldview that implies an irreconcilable conflict between the holy God and the worldly human. She interprets her vision of contradictory attributes between divinity and mortality, one celestial and the other earthly, by creating and applying musical symbols. Thus, Gubaidulina employs the concept of binary opposition as many of her works involve extreme contrasts, conflicts, and tension. In this document I will analyze the musical content in detail. Then I will examine the symbolic devices in terms of dichotomy, which explains how Gubaidulina uses the same musical metaphor in her works and how she employs and develops the musical devices to represent her religious vision. I expect that those findings of my study would explain the symbolic aspect of the music of Sofia Gubaidulina, music rooted in her spiritual insight. ii Dedicated to my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I praise my Lord who made it possible to complete this document.