File-786652279.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broschüre Glaube & Religion

LAND OBERÖSTERREICH GLAUBE & RELIGION Gesetzlich anerkannte Kirchen, Religions- und Bekenntnisgemein- schaften in Oberösterreich Oö. Religionsbeirat Stand: September 2020 2 Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren! Unterschiedliche Religionen und Welt- Bekenntnisgemeinschaften in unserem anschauungen dürfen uns nicht daran Land. Dabei soll diese Broschüre eine hindern, zum Besten aller zusammen- nützliche Handreichung sein. zuarbeiten. Diese Zusammenarbeit hat in Oberösterreich bereits Tradition. Es gibt ein gutes Miteinander der Religio- Mag. Thomas Stelzer nen in unserem Land. Landeshauptmann Der Oberösterreichische Religionsbei- Stefan Kaineder rat, zu dem alle gesetzlich anerkannten Landesrat Religions- und Bekenntnisgemeinschaf- Dr. Helmut Obermayr ten eingeladen wurden, hat sich zur Koordinator Aufgabe gemacht, den respektvollen Umgang der Religionen untereinander ins Alltagsleben der Menschen zu über- setzen. Denn der Respekt vor dem anderen ist ein zentraler Schlüssel zur Integration. Voraussetzung dafür ist aber notwendi- ges Wissen über Religions- und 3 Hinweis Zur Erstellung der vorliegenden Informationssammlung wurden alle im oö. Religionsbeirat mitwirkenden – das sind mit einer Ausnahme alle in Oberösterreich vertretenen – Religions- und Bekenntnisgmeinschaften um Zurverfügungstellung von Basisinformationen ersucht. Diese Informa- tionssammlung basiert somit auf den eigenen Angaben der jeweiligen Gemeinschaften. 4 Inhalt GESETZLICH ANERKANNTE KIRCHEN UND RELIGIONSGESELLSCHAFTEN (und ihre Vertretung in Oberösterreich) 6 Altkatholische -

The Perfection of the Soul in Fakhr Al-Dīn Al-Rāzī's Al-Sirr

THE PERFECTION OF THE SOUL IN FAKHR AL-DĪN AL-RĀZĪ‘S AL-SIRR AL-MAKTŪM MICHAEL-SEBASTIAN NOBLE A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Combined Historical Studies The Warburg Institute University of London 2017 1 I declare that the work presented in this dissertation is my own. Signed: _________________________________ Date: _____________________ 2 Abstract Al-Sirr al-Maktūm is one of the most compelling theoretical and practical accounts of astral magic written in the post-classical period of Islamic thought. Of central concern to its reader is to understand why the great philosopher- theologian, Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (d.606/1210) should have written it. The occult practices described therein are attributed to the Sabians, a historical group who lived in Ḥarrān in Upper Mesopotamia. Representing the last vestiges of Ancient Mesopotamian paganism during the early Islamic period, their religion involved the veneration of the seven planets, which they believed were ensouled celestial beings and the proximate causes of all sublunary change. By means of such astrolatry they were able, remotely, to change reality in ways which defied the customary pattern of causation in this world. The main focus of al-Rāzī‘s treatment of their practice is a long ritual during which the aspirant successively brings under his will each of the seven planets. On completion of the ritual, the aspirant would have transcended the limitations of his human existence and his soul would have attained complete perfection. This thesis will argue that for al-Rāzī, the Sabians constituted a heresiological category, representative of a soteriological system which dispensed with the need for the Islamic institution of prophethood. -

Second Series - Furoo' Al-Deen Syllabus (Acts of Worship) Second Series - Furoo' Al-Deen Syllabus (Acts of Worship)

Second Series - Furoo' Al-Deen Syllabus (Acts of Worship) Second Series - Furoo' Al-Deen Syllabus (Acts of Worship) Composed by: Revised by: Shaikh Adel Al Shoala Prof. Abd Ali Mohammed Hassan Shaikh Hussain Altaweel Dr. Salman Al-Halwachi Mr. Ameer abd al-Nabi Hussain Shaikh Fuad Mobarak Mr. Majeed Meelad Sayyed Fadel Al Alawi Translated by: Mr. Jaffar Al Shehaby Mr. Jawad Meelad First edition - 1431 – 2010 Publisher: Olamaa Islamic Council Designed by: Mohsin AL-Khabbaz Introduction 4 In the name of Allah, the Most Beneficent, the Most Merciful Praise be to Allah, the Almighty, the Lord of the Worlds, and we extend our prayers and salutation to our master, the holy prophet and his immaculate and virtuous descendants. This series "Islam is my religion", aims at providing the student with educational opportunities drawn from his practical life experience, and extracted from his needs of the stage he is living in. The series has been formulated with the objective of making his behavior comply with the requirement of the Shariah, yet in line with his environment and his society. This book is one of the course units of the second volume of the series: " Islam is my religion" published by Islamic Olamaa Council in Bahrain. It tackles the acts of worship in general terms as given in the scholarly books to enable the student to familiarize himself with the most important religious laws that he is required to observe in his present age group. It has been presented in simple and clear language without any complicated terms usually used in the books of religious jurisprudence. -

MODULE 1 the CREATOR and HIS CREATION This Module Is

MODULE 1 MODULE 2 MODULE 3 MODULE 4 MODULE 5 MODULE 6 MODULE 7 MODULE 8 THE CREATOR AND HIS CREATION DIVINE GUIDANCE RASULULLAH THE A’IMMAH THE PERIOD OF GHAYBAH ROADMAP TO SELF-PURIFICATION S0CIETAL WELLBEING RETURN TO THE CREATOR This module is dedicated to Allah and to man's Having created us, Allah continues to nurture and This module is a continuation of the concept of This module is a further continuation of the This module is dedicated to the Imam of our time, This module examines the distinction between the This module is a continuation of the roadmap to This module completes the cycle that began with relationship with his Creator. It covers Tawhid guide us. This module covers the lutf and adalah of Divine Guidance but focuses on the process that concept of Divine Guidance but focuses on the Imam al-Mahdi (a). It covers the concept of body and the soul and discusses the roadmap self-purification but at the societal instead of the the creation of Allah and ends with the return to (monotheism) in great depth, discussing the Allah, and explores the understanding of the the Prophet of Islam used to communicate his divinely appointed successors of Rasulullah (s) ghaybah, its minor and major phases, the long life (shari'ah) sent down by Allah for self-purification in individual level. Islam is not just a religion of Him. It covers the process of death, the existence of Allah, His unity and His various various schools of Islamic theology, especially in Message and to live it. -

Contested Identities and the Muslim Qaum in Northern India: C

)103/ ip 1, Contested Identities and the Muslim Qaum in northern India: c. 1860-1900 S Akbar Zaidi Churchill College University of Cambridge CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract Contested Identities and the Muslim Qaum in northern India: c. 1860-1900 S Akbar Zaidi Using primarily published sources in Urdu from the second-half of the nineteenth century, my thesis presents evidence with regard to north Indian Muslims, which questions the idea of a homogenous, centralising, entity. at times called the Muslim community. qaum, ummah or nation. Using a large number of second-tier publicists' writings in Urdu, the thesis argues that the self-perceptions and representations of many Muslims. were far more local. parochial, disparate, multiple, and highly contested. The idea of a homogenous, levelling, sense of collective identity. or an imagined community, seem wanting in this period. This line of evidence and argumentation, also has important implications for locating the moment of separatism and identity formation amongst north Indian Muslims, and argues that this happened much later than has previously been imagined. Based on this, the thesis also argues against an anachronistic or teleological strain of historiography with regard to north Indian Muslims of this period. The main medium through which these arguments are debated, is through the Urdu print world, where a large number of new sources have been presented which underscore this difference, more than this uniformity. Whether it was in religious debates, debates around the attempt to unify - as part of a qaum - or around the for be humiliation literature reasons Muslims to at a point of zillat - utter - the points to multiple and diverse interpretations, causes and solutions. -

Imam Muhammad Shirazi

Imam Muhammad Shirazi War, Peace and Non-violence An Islamic perspective Translated by Ali ibn Adam Z. Olyabek fountain books BM Box 8545 London WC1N 3XX UK www.fountainbooks.com In association with Imam Shirazi World Foundation 1220 L. Street N.W. Suite # 100 – 333 Washington, D.C. 20005 – 4018 U.S.A. www.ImamShirazi.com Second edition 2001 Third edition 2003 © fountain books All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of fountain books. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1-903323-04-5 ii Contents PART ONE 3 Islam’s View on War 5 War is the worst thing known to mankind 5 War is an illness 5 War as the last resort 6 Islam through conviction 6 The Jizyah tax . finally 6 The Prophet’s wars were fought in self defence 8 The least amount of casualties 9 Excess of killing and torturing 9 Frightening scenes of the brutality of the Moguls 10 Modern wars are no less brutal 12 The increase of the dangers of war in the modern age 13 The other effects of war 14 Towards a comprehensive peace 15 Cutting the roots of war 16 Exposing ‘War by proxy’ 18 War is an extraordinary situation 19 Islam’s Guidance on War 22 The condition of parental permission 22 Jihad is not incumbent upon certain groups 23 Jihad is not incumbent upon women 24 War is not permitted in the absence of the just Imam 26 The invitation to Islam . -

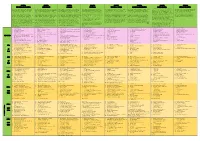

MCE Fiqh Overview

FIQH CONTENT REVIEW Salah Furu’ ad-din Miscellaneous Relationships Importance Salah Timing Bulugh Fasting Wudhu Haram & halal Hajj foods Tayammum Zakah Israf Rukn & Khums Ghayr rukn visiting masajid Jihad FIQH CONTENT IN TARBIYAH CURRICULUM BANDS C - F Introduction Please see below a matrix which outlines the location of the various fiqh topics present in the Tarbiyah curriculum. It allows you to view which module and lesson number each fiqh topic appears in, and provides a cross reference to the index of the Islamic Laws book by Ayatullah Syd al-Sistani. Module Total No. Of Lessons Per Module Module title Number Band C Band D Band E Band F 1 Allah and His Creation 11 12 12 10 2 Divine Guidance 11 11 11 11 3 Rasulullah (s)- Communicating the Message 11 11 12 12 4 The A’immah (a)- Safeguarding the Message 12 12 12 10 5 Upholding the Message during Ghaybah 11 11 12 11 6 Roadmap to Self-purification 10 11 12 11 7 Societal Wellbeing 11 12 11 11 8 The Hereafter (Ma’ad) 9 9 11 11 FIQH CONTENT IN TARBIYAH CURRICULUM BAND C Module Lesson Page Band Lesson Title Type Content Category No. & Title No. No. C 1 Who is Allah? 20 Fiqh Facts Following a Mujtahid Taqlid C 2 Shaytan's Promise to Misguide Us 29 Fiqh Facts Too many doubts in wudhu and salah Salah C 3 Why did Allah create us? 35 Fiqh Facts Niyyah of qurbatan ila Allah Misc C 4 The need of following a religion 39 Fiqh Facts Following laws of country Misc C 5 Islam - the path to perfection 46 Fiqh Facts Islam is a mutahhirat Mutahhirat C 6 Understanding kufr When is wudhu wajib; when is wudhu -

Imam Muhammad Shirazi the Shi'a and Their Beliefs

Imam Muhammad Shirazi The Shi'a and their Beliefs Translated by Ali Adam Presented by www.ziaraat.com fffountain books BM Box 8545 London WC1N 3XX UK www.fountainbooks.net In association with Imam Shirazi World Foundation 1220 L. Street N.W. Suite # 100 – 333 Washington, D.C. 20005 – 4018, U.S.A. www.ImamShirazi.com Frist English edition, 2008 ISBN 1-903323-12-6 © fountain books All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of fountain books. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ii Presented by www.ziaraat.com Contents Foreword.........................................................................................1 The Shi!a in Brief ...........................................................................3 The Creed of Shi!a and Sunna....................................................6 Introducing the Shi!a ......................................................................8 Islam in the View of the Shi!a......................................................11 1. Shi!a Doctrine ......................................................................11 2. Shi!a View of Islamic Law...................................................13 The Five Laws .....................................................................14 Sources of Islamic Law........................................................14 -

Extremist Shiites the Ghulat Sects

Extremist Shiites The Ghulat Sects Matti Moosa SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright © 1988 by Syracuse University Press Syracuse, New York 13244-5160 First published 1987 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED First Edition 93 92 91 90 89 88 654321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. T" Extremist Shiites is published with the support of the Office of the Vice-President for Academic Affairs, Gannon University, Erie, Pennsylvania. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moosa, Matti. Extremist Shiites. (Contemporary issues in the Middle East) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Shi'ah. 2. Sufism. 3. Islamic sects. 4. Nosairians. I. Title. II. Series. BP193.5.M68 1987 297'.82 87-25487 ISBN 0-8156-2411-5 (alk. paper) MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA r To Hans, Mark, Petra, and Jessica With Love MATTI MOOSA is Professor of History at Gannon University and the author of The Origins of Modern Arabic Fiction and The Maronites in History (Syracuse University Press). Contents Preface ix Introduction xiii 1 The Shabak 1 2 The Bektashis 10 3 The Safawis and Kizilbash 21 4 The Bektashis, the Kizilbash, and the Shabak 36 5 The Ghulat's "Trinity" 50 6 The Miraculous Attributes of Ali 66 7 The Family of the Prophet 77 8 Religious Hierarchy 88 9 The Twelve Imams 92 10 The Abdal 110 11 Rituals and Ceremonies 120 12 Social Customs 144 13 Religious Books 152 14 The Bajwan and Ibrahimiyya 163 15 The Sarliyya-Kakaiyya -

Analisis Kritis Metodologi Periwayatan Hadits Syiah (Bahrul Ulum Dan Zainudin MZ)

Analisis Kritis Metodologi Periwayatan Hadits Syiah (Bahrul Ulum dan Zainudin MZ) ANALISIS KRITIS METODOLOGI PERIWAYATAN HADITS SYIAH (Studi Komparatif Syiah-Sunni) Bahrul Ulum dan Zainudin MZ PT. Lentera Jaya Abadi Surabaya Telp. (031) 8679046 / HP. 08132155100 E-Mail: [email protected] IAIN Sunan Ampel Surabaya E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract: Shi’i Ithna Asy’ariyah is a group of Muslims who have different hadith books with a majority of Muslims. In the making of the book, the Shiite cleric has its own methods, particularly in the narration. This study aims to determine the method of narration Shia hadith. The authors use historical methods and critical analysis. Hitorical method used to determine the historical journey through the establishment of ideas in the book-making, paradigm used to look at the use of the method, and background affect his thinking. From the results of this research is basically the Shia do not have an accurate and scientific methods in determining the hadith narration track. Since the beginning, the scholars they pay less attention to this issue. They began to conduct studies after receiving criticism from Sunni clerics and modeled after the method used by the Sunnis. However, they still have difficulties because they do not have enough material to do that. Key words: shi’i, hadith, transmitter Abstrak: Syi’ah Itsna Asy’ariyah adalah sekelompok Muslim yang memiliki buku- buku hadits yang berbeda dengan mayoritas Muslim. Dalam penyusunan buku ini, ulama Syiah memiliki metode sendiri, terutama dalam periwayatan hadis. Makalah ini bertujuan untuk mengetahui metode narasi hadits Syiah. Penulis menggunakan metode historis dan analisis kritis. -

Shias and Their Beliefs

SHIAS AND THEIR BELIEFS Written By SHAIKH MIR ASEDULLAH QUADRI Sahih Iman Publication i Copyright © SAHIH IMAN 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. ii PREFACE بِسم هللا الرحم ِن الرحي م الحمد هلل رب العالمين، والصﻻة والسﻻم على سيدنا محمد وعلى آله وصحبه أجمعين meaning the followers of Hadhrat (رضئ هللا تعالی عنہ) The word Shia is derived from Shiatu Ali as divinely appointed legitimate (رضئ هللا تعالی عنہ)Shias regard Hadhrat Ali .(رضئ هللا تعالی عنہ) Ali and disregard and often denounce the (صلى هللا عليه و آله وسلم) successor of Prophet Mohammad (رضئ هللا تعالی عنہم اجمعين) (first three rightly guided Caliphs (Khulfa-e-Rashideen The book is written with the intention to place before people facts in this context. We hope readers will benefit from this book. iii CONTENTS SHIA GROUPS IN THE WORLD 1 SHIA BELIEFS 4 iv SHIA GROUPS IN THE WORLD There are hundreds of Shia Groups in the world. Prominent among them are as follows. (1) Tafdheeliyah Shias, (2) Tabarraiyyah Shias, (3) Ghullat Shias, (4) Sabaaiyyah Shias, (5) Mufaddhaliyyah Shias, (6) Sarrghiyyah Shias or Sareefiyyah Shias (7) Bazeeghiyyah Shias (8) Kaamiliyyah Shias, (9) Mughiriyyah Shias, (10) Janaahiyyah Shias, (11) Bayaaniyyah Shias, (12) Mansuriyyah -

The Mystery of the Shi'a

2nd Chance Books for Prisoners Imam Mahdi Foundation is a non-profit organization that was founded in the United Kingdom. This organization has many other projects that it manages in the UK as well as the United States. One of these initiatives that Imam Mahdi foundation has started is a program to send free books to prisoners. This program is called 2nd Chance Books, which is dedicated to the descendant of the Holy Prophet (pbuh); The 11th Imam Hassan Al-Askari (pbuh) who spent the majority of his life in prison and under house arrest by the corrupt ruler of the time. The incarceration rate in the USA is the highest in the world. While Americans only represent 5% of the worlds population nearly one-quarter of the entire worlds inmates have been incarcerated in the USA. The prison population in the USA is 2.3 million. Most of these prisoners will fall victim to the cycle of the revolving door and become repeat offenders if they do not have the proper resources to educate themselves properly while serving their sentences. This program will provide the proper tools for change; Free Islamic books on belief, ethics, morality and family structure in Islam. They can use these books as a tool for self-development and to reform themselves and also their friends, loved ones and communities upon their release. Some of the many benefits of this program are changing prisoners bad habits into good ones; achieving social reform by teaching the morals and ethics of the Holy Prophet and his Holy Household (pbut), molding leaders; producing better citizens who will be active in helping their communities upon their release, promoting awareness of the true teachings of Islam as taught by Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) and his Holy Household (pbut) and to remove misinformation and misconceptions about Islam and Muslims from the peoples minds.