Apple Computer's Financial Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spirit of the Heights Thomas H. O'connor

THE SPIRIT OF THE HEIGHTS THOMAS H. O’CONNOR university historian to An e-book published by Linden Lane Press at Boston College. THE SPIRIT OF THE HEIGHTS THOMAS H. O’CONNOR university historian Linden Lane Press at Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts Linden Lane Press at Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue 3 Lake Street Building Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts 02467 617–552–4820 www.bc.edu/lindenlanepress Copyright © 2011 by The Trustees of Boston College All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval) without the permission of the publisher. Printed in the USA ii contents preface d Thomas H. O’Connor v Dancing Under the Towers 22 Dante Revisited 23 a “Dean’s List” 23 AHANA 1 Devlin Hall 24 Alpha Sigma Nu 2 Donovan, Charles F., S.J. 25 Alumni 2 Dustbowl 25 AMDG 3 Archangel Michael 4 e Architects 4 Eagle 27 Equestrian Club 28 b Bands 5 f Bapst Library 6 Faith on Campus 29 Beanpot Tournament 7 Fine Arts 30 Bells of Gasson 7 Flutie, Doug 31 Black Talent Program 8 Flying Club 31 Boston “College” 9 Ford Tower 32 Boston College at War 9 Fulbright Awards 32 Boston College Club 10 Fulton Debating Society 33 Bourneuf House 11 Fundraising 33 Brighton Campus 11 Bronze Eagle 12 g Burns Library 13 Gasson Hall 35 Goldfish Craze 36 c Cadets 14 h Candlemas Lectures 15 Hancock House 37 Carney, Andrew 15 Heartbreak Hill 38 Cavanaugh, Frank 16 The Heights 38 Charter 17 Hockey 39 Chuckin’ Charlie 17 Houston Awards 40 Church in the 21st Century 18 Humanities Series 40 Class of 1913 18 Cocoanut Grove 19 i Commencement, First 20 Ignatius of Loyola 41 Conte Forum 20 Intown College 42 Cross & Crown 21 Irish Hall of Fame 43 iii contents Irish Room 43 r Irish Studies 44 Ratio Studiorum 62 RecPlex 63 k Red Cross Club 63 Kennedy, John Fitzgerald 45 Reservoir Land 63 Retired Faculty Association 64 l Labyrinth 46 s Law School 47 Saints in Marble 65 Lawrence Farm 47 Seal of Boston College 66 Linden Lane 48 Shaw, Joseph Coolidge, S.J. -

Important ESA Hearing Slated Nov. 1 — Judge Appears to Forest Service (USFS) and Feder- Tion of Habitat Deemed Necessary for Tiffs

02page1.qxd 10/24/02 5:00 PM Page 1 The National Livestock Weekly October 28, 2002 • Vol. 82, No. 02 “The Industry’s Largest Weekly Circulation” www.wlj.net • E-mail: [email protected] • [email protected] • [email protected] A Crow Publication September placement data good news — Placements good tember placements also added to ing September. While that figure is for feeder cattle, the bullishness. two percent more than last year, it In terms of near-term fed mar- was between four and 20 percent marketings “neutral” kets — late October and November below analysts’ pre-report expec- September Feedlot for near-term feds. — analysts said September mar- tations. In addition, the figure is al- keting data really didn’t create most 20 percent below the number Placements By Steven D. Vetter much of a price trend one way or the of cattle placed into feedlots during WLJ Editor other. Analysts also said delivery to September 2000. For the entire (Weight distribution for total U. S.) Reactions to USDA’s most recent packers over the next couple of U.S., September placements were Cattle-on-Feed (C-o-F) Report were, weeks will be a key price indicator pegged at 2.19 million head, also across the board, bullish, particu- over the next month or two. two percent more than last year. 2002 800 lbs. & heavier (23.08%) larly with the much lower-than-ex- According to USDA’s seven-state September marketings, for the pected number of feedlot place- report — for Arizona, California, seven-state report, totaled 1.57 mil- ments in September. -

Business People Who Died in 2010

Business people who died in 2010 January-2010 Harry Männil Born May 17, 1920(1920-05-17) Tallinn, Estonia Died January 11, 2010(2010-01-11) (aged 89) San José, Costa Rica Resting Costa Rica place Residence Estonia (1920–1943) Venezuela (1946–2010) Ethnicity Estonian Citizenship Estonian, Venezuelan Occupation Businessman Known for Entrepreneurship, art collecting, alleged war crimes Spouse Masula D'Empaire Children 4 Relatives Ralf Männil (brother) Harry Männil (May 17, 1920 Tallinn, Estonia – January 11, 2010 San José, Costa Rica) was an Estonian businessman, art collector, and cultural benefactor in several countries. In 1946, he moved to Venezuela, where he lived for the rest of his life. He was a successful businessman and part owner of ACO Group, a large Venezuelan automotive concern. He formed his own company in 1994. Harry Männil was accused by the Simon Wiesenthal Center of having participated in the murder of Jews while he worked for the political police in 1941–1942 during the German occupation of Estonia. After a four-year probe, Estonian investigators could find no evidence against him and he was cleared of the charges. Harry Männil was born into an iron salesman's family on May 17, 1920, in Tallinn, Estonia, and spent his childhood in Pääsküla, Tallinn. [1] [2] He graduated from the Gustav Adolf Grammar School in 1938 and from 1939–40 studied economics at the University of Tartu and the Tallinn University of Technology.[1] In the summer of 1941, during the Soviet occupation, he hid in a forest to avoid the mobilization.[1] Männil joined the political police of the Estonian Self-Administration as an assistant in September 1941. -

Intro to Ios

Please download Xcode! hackbca.com/ios While installing, ensure you have administrator access. Download our sound and image files at hackbca.com/ios - you’ll be using them in this workshop. iOS Development with SwiftUI Anthony Li Room 138 Link Welcome [HOME ADDRESS CENSORED] Anthony Li - https://anli.dev ATCS ‘22 Just download it “The guy who made YourBCABus” 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer History • 13.8 billion years ago, there was a Big Bang. 1984 OG GUI The Macintosh 1984 Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life, or do you want to come with me and change the world? Steve Jobs John Sculley 19841985 sure i guess btw ur fired now Steve Jobs John Sculley 1985 • Unix-based GUI! • Object-oriented programming! • Drag-and-drop app building! Steve Jobs • First computer to host a web server! ONLY $6,500! NeXTSTEP OS AppKit Foundation UNIX 1997 btw ur hired now. first give me a small loan of $429 million Steve Jobs 1997 Apple buys NeXT. Mac OS X AppKit Foundation UNIX 2007 iPhone OS AppKit “UIKit” Foundation UNIX 2014 Swift Objective-C 2019 SwiftUI UIKit iOS Your Apps UIKit SwiftUI Foundation Quartz Objective-C Swift UNIX 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer Text Button Image List struct MyView: Button View View View Button 1 History 2 Introduction to Swift 3 Duck Clicker 4 hackBCA Schedule Viewer Master Detail Master Detail Master Detail iOS Your Apps UIKit SwiftUI Foundation Quartz Objective-C Swift UNIX SwiftUI UIKit MapKit: MKMapView UIKit-based. -

Finance with Connect Plus 1St Edition Kindle

M: FINANCE WITH CONNECT PLUS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marcia Cornett | 9780077506056 | | | | | M: Finance with Connect Plus 1st edition PDF Book That said, if you're out of iCloud storage space or prefer to have more control over your device backup, then you can use your computer. Important Information. In News. N95 vs. Always collect your card and transaction slip once you have completed your transaction. We will continue to create value for all our stakeholders and emerge as a 'Best-in-Class' Bank that is committed to sustainable economic growth. All shipping options assumes the product is available and that it will take 24 to 48 hours to process your order prior to shipping. Archived from the original on April 15, Apply Now. Arthur D. Individual Saving Account Get more out of your savings. For shipments to locations outside of the U. Doing so will backup all of your email accounts and app passwords, saving you from having to enter those whenever you have to restore your phone. Retrieved February 1, Personal Loan Spending is rewarding. Instructor Tools. Retrieved May 12, Views Read Edit View history. Updates aren't a perfect process, and sometimes things go wrong. No need to swipe your card or enter PINs while waiting in a queue. M: Finance with Connect Plus 1st edition Writer The easiest way to do that is just to open it, and if you see a prompt to update it, then do follow the steps. Quick Pay. Once it's installed, check out some of our favorite features , including the new homescreen that includes widgets -- that you can customize. -

Professor Won Woo Ro, School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering Yonsei University the Intel® 4004 Microprocessor, Introdu

Professor Won Woo Ro, School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering Yonsei University The 1st Microprocessor The Intel® 4004 microprocessor, introduced in November 1971 An electronics revolution that changed our world. There were no customer‐ programmable microprocessors on the market before the 4004. It propelled software into the limelight as a key player in the world of digital electronics design. 4004 Microprocessor Display at New Intel Museum A Japanese calculator maker (Busicom) asked to design: A set of 12 custom logic chips for a line of programmable calculators. Marcian E. "Ted" Hoff Recognized the integrated circuit technology (of the day) had advanced enough to build a single chip, general purpose computer. Federico Faggin to turn Hoff's vision into a silicon reality. (In less than one year, Faggin and his team delivered the 4004, which was introduced in November, 1971.) The world's first microprocessor application was this Busicom calculator. (sold about 100,000 calculators.) Measuring 1/8 inch wide by 1/6 inch long, consisting of 2,300 transistors, Intel’s 4004 microprocessor had as much computing power as the first electronic computer, ENIAC. 2 inch 4004 and 12 inch Core™2 Duo wafer ENIAC, built in 1946, filled 3000‐cubic‐ feet of space and contained 18,000 vacuum tubes. The 4004 microprocessor could execute 60,000 operations per second Running frequency: 108 KHz Founders wanted to name their new company Moore Noyce. However the name sounds very much similar to “more noise”. "Only the paranoid survive". Moore received a B.S. degree in Chemistry from the University of California, Berkeley in 1950 and a Ph.D. -

Beckman, Harris

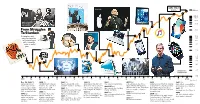

CHARM 2007 Full Papers CHARM 2007 The Apple of Jobs’ Eye: An Historical Look at the Link between Customer Orientation and Corporate Identity Terry Beckman, Queen’s University, Kingston ON, CANADA Garth Harris, Queen’s University, Kingston ON, CANADA When a firm has a strong customer orientation, it Marketing literature positively links a customer orientation essentially works at building strong relationships with its with corporate performance. However, it does not customers. While this is a route to success and profits for a elaborate on the mechanisms that allow a customer firm (Reinartz and Kumar 2000), it is only successful if a orientation to function effectively. Through a customer customer sees value in the relationship. It has been shown orientation a firm builds a relationship with the customer, that customers reciprocate, and build relationships with who in turn reciprocates through an identification process. companies and brands (Fournier 1998). However, in This means that the identity of a firm plays a significant forming a relationship with the firm, customers do this role in its customer orientation. This paper proposes that through an identification process; that is, they identify with customer orientation is directly influenced by corporate the firm or brand (e.g., Battacharya and Sen 2003; identity. When a firm’s identity influences its customer McAlexander and Schouten, Koening 2002, Algesheimer, orientation, firm performance will be positively impacted. Dholakia and Herrmann 2005), and see value in that An historical analysis shows three phases of Apple, Inc.’s corporate identity and relationship. While a customer life during which its identity influences customer orientation establishes a focus on customers, there are many orientation; then where Apple loses sight of its original different ways and directions that a customer focus can go. -

IBM Powerpc 970 (A.K.A. G5)

IBM PowerPC 970 (a.k.a. G5) Ref 1 David Benham and Yu-Chung Chen UIC – Department of Computer Science CS 466 PPC 970FX overview ● 64-bit RISC ● 58 million transistors ● 512 KB of L2 cache and 96KB of L1 cache ● 90um process with a die size of 65 sq. mm ● Native 32 bit compatibility ● Maximum clock speed of 2.7 Ghz ● SIMD instruction set (Altivec) ● 42 watts @ 1.8 Ghz (1.3 volts) ● Peak data bandwidth of 6.4 GB per second A picture is worth a 2^10 words (approx.) Ref 2 A little history ● PowerPC processor line is a product of the AIM alliance formed in 1991. (Apple, IBM, and Motorola) ● PPC 601 (G1) - 1993 ● PPC 603 (G2) - 1995 ● PPC 750 (G3) - 1997 ● PPC 7400 (G4) - 1999 ● PPC 970 (G5) - 2002 ● AIM alliance dissolved in 2005 Processor Ref 3 Ref 3 Core details ● 16(int)-25(vector) stage pipeline ● Large number of 'in flight' instructions (various stages of execution) - theoretical limit of 215 instructions ● 512 KB L2 cache ● 96 KB L1 cache – 64 KB I-Cache – 32 KB D-Cache Core details continued ● 10 execution units – 2 load/store operations – 2 fixed-point register-register operations – 2 floating-point operations – 1 branch operation – 1 condition register operation – 1 vector permute operation – 1 vector ALU operation ● 32 64 bit general purpose registers, 32 64 bit floating point registers, 32 128 vector registers Pipeline Ref 4 Benchmarks ● SPEC2000 ● BLAST – Bioinformatics ● Amber / jac - Structure biology ● CFD lab code SPEC CPU2000 ● IBM eServer BladeCenter JS20 ● PPC 970 2.2Ghz ● SPECint2000 ● Base: 986 Peak: 1040 ● SPECfp2000 ● Base: 1178 Peak: 1241 ● Dell PowerEdge 1750 Xeon 3.06Ghz ● SPECint2000 ● Base: 1031 Peak: 1067 Apple’s SPEC Results*2 ● SPECfp2000 ● Base: 1030 Peak: 1044 BLAST Ref. -

From Struggles to Stardom

AAPL 175.01 Steve Jobs 12/21/17 $200.0 100.0 80.0 17 60.0 Apple co-founders 14 Steve Wozniak 40.0 and Steve Jobs 16 From Struggles 10 20.0 9 To Stardom Jobs returns Following its volatile 11 10.0 8.0 early years, Apple has 12 enjoyed a prolonged 6.0 period of earnings 15 and stock market 5 4.0 gains. 2 7 2.0 1.0 1 0.8 4 13 1 6 0.6 8 0.4 0.2 3 Chart shown in logarithmic scale Tim Cook 0.1 1980 ’82 ’84 ’86’88 ’90 ’92 ’94 ’96 ’98 ’00 ’02 ’04 ’06’08 ’10 ’12 ’14 ’16 2018 Source: FactSet Dec. 12, 1980 (1) 1984 (3) 1993 (5) 1998 (8) 2003 2007 (12) 2011 2015 (16) Apple, best known The Macintosh computer Newton, a personal digital Apple debuts the iMac, an The iTunes store launches. Jobs announces the iPhone. Apple becomes the most valuable Apple Music, a subscription for the Apple II home launches, two days after assistant, launches, and flops. all-in-one desktop computer 2004-’05 (10) Apple releases the Apple TV publicly traded company, passing streaming service, launches. and iPod Touch, and changes its computer, goes public. Apple’s iconic 1984 1995 (6) with a colorful, translucent Apple unveils the iPod Mini, Exxon Mobil. Apple introduces 2017 (17 ) name from Apple Computer. Shares rise more than Super Bowl commercial. Microsoft introduces Windows body designed by Jony Ive. Shuffle, and Nano. the iPhone 4S with Siri. Tim Cook Introduction of the iPhone X. -

Effectively Communicating Y Ating Your Department's Worth

stayinging relrelevant Effectively communicatatinging yyour department’s worth Getting thee Cart before the Horse Stayinging ReRelevant Everythingng I lealearned about marketinarketing I learned from an Apple & the Circus Let’s talklk aboabout Apple Let’s Talkalk aboabout Apple 1976 - Steve Wozniak designs new computeruter (A(Apple I) & 21 year old Steve Jobs convinces him to take it commercial 1977 - Apple II becomes instant success 1980 - Apple sales soar to $1 million-a-yearear & ccompany goes public 1983 - John Sculley recruited to help buildld compcompany 1984 - Big Brother Superbowl ad 1985 - Jobs ousted by Sculley and board 1991 - Alliances with IBM and Motorola 1993 - Sculley ousted after handheld Newtonwton prproject fails 1984 SuperbSuperbowl Ad QuickTime™Time™ and a decompresompressor are needed to see ththis picture. Let’s Talkalk aboabout Apple 1976 - Steve Wozniak designs new computer (Apple 1) & 21 year old Steve Jobs convinces him to tak it commercial 1977 - Apple II becomes instant success 1980 - Apple sales soar to $1 million-a-year & compacompany goes public 1983 - John Sculley recruited to help build companypany 1984 - Big Brother Superbowl ad 1985 - Jobs ousted by Sculley and board 1991 - Alliances with IBM and Motorola 1993 - Sculley ousted after handheld Newton project fails 1996 - Apple acquires NeXT Software And then 1997 hhappened... QuickTime™Time™ and a decompreompressor are needed to see ththis picture. Communicatingicating the value Thinknk DiffeDifferent Marketing is about valulueses. This is a very complicated world. It's's a ververy noisy world. We' re not going to get a chanancece fofor people to remember a lot about us. No compapanyny isis. -

Hhoouullttoonnhhiigghhsscchh

A Publication for Houlton High School Alumni & Friends Houlton High School Spring/SummerA l2007um n i N eVolumews 10, Issue 2 A YEAR TO CELEBRATE The year 2007 is defi- the Science Lab, nitely a year to cele- Auditorium curtain, Gym brate. It is hard to Floor and Soccer Lights believe, but this year to a new Fitness Room, marks the 10th year lockers, Library chairs since the Houlton High and professional devel- School Alumni opment. The Board has Association was created. budgeted $10,000 this As we have told in the year toward a special past, the Alumni project(s) at the school. Association was an idea Yes, the Alumni born on a lawn mower. Association has come a Lauren Peabody long way in ten years. Fitzpatrick had the idea We hope to continue to and she took it and ran grow in the coming with it. She was the cat- years and thank all of alyst for creating an you for your support in organization that has getting us where we are done so much in a short today and taking us time. where we are going. That first year, we The Alumni were so excited to attend Association’s 10th Last Chapel and present anniversary is not, how- $1,000 in scholarships – ever, the only celebra- 2 $500 scholarships. An tion going on this year. amount we matched for The Town of Houlton is the first four or five years of our existence. In comparison, this year celebrating it’s Bicentennial. Two hundred years ago this town was over $37,000 has been budgeted for scholarship presentations. -

The Identification and Division of Steve Jobs

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Scott M. Anderson for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Speech Communication, Speech Communication, and English presented on May 17, 2012. Title: The Identification and Division of Steve Jobs Abstract approved: Mark P. Moore On April 1, 1976, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak entered into a partnership agreement to found Apple Computer. In the decade that followed, Apple experienced remarkable growth and success, as Jobs catapulted Apple to the Fortune 500 list of top‐flight companies faster than any other company in history. Under direction of Jobs, Apple, an idea that started in a garage, transformed into a major force in the computer industry of the 1980s. Though Jobs’ leadership undoubtedly influenced Apple’s success during this time, in 1995, he was forced to resign, when conflicts mounted at the executive level. Using Kenneth Burke’s theory of identification and the dramatistic process, this thesis examines Jobs’ discourse through a series of interviews and textual artifacts. First, I provide a framework for Jobs’ acceptance and rejection of the social order at Apple, and then consider the ways in which Jobs identified with employee and consumer audiences on the basis of division. Analysis shows that Jobs identified with individual empowerment, but valued separation and exclusivity. Jobs’ preference to create identification through division, therefore, established the foundation for new identifications to emerge. The findings of this study suggest that division has significant implications for creating unity. ©Copyright by Scott M. Anderson May 17, 2012 All Rights Reserved The Identification and Division of Steve Jobs by Scott M.