The Spirit of the Heights Thomas H. O'connor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACADEMIC CATALOG 2019-2020 Contents

ACADEMIC CATALOG 2019-2020 Contents Mission Statement ...................................................................................................................................... 1 President’s Message ................................................................................................................................... 2 Visiting ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 History .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Regis College at a Glance ......................................................................................................................... 5 Accreditation .............................................................................................................................................. 7 The Regis Pathways of Achievement ...................................................................................................... 9 Associate Degree Programs at a Glance ............................................................................................... 13 Regis Facilities and Services................................................................................................................... 16 General College Policies and Procedures............................................................................................. 20 Accreditation, State -

Misdemeanor Warrant List

SO ST. LOUIS COUNTY SHERIFF'S OFFICE Page 1 of 238 ACTIVE WARRANT LIST Misdemeanor Warrants - Current as of: 09/26/2021 9:45:03 PM Name: Abasham, Shueyb Jabal Age: 24 City: Saint Paul State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/05/2020 415 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFFIC-9000 Misdemeanor Name: Abbett, Ashley Marie Age: 33 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 03/09/2020 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Abbott, Alan Craig Age: 57 City: Edina State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 09/16/2019 500 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Disorderly Conduct Misdemeanor Name: Abney, Johnese Age: 65 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/18/2016 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Shoplifting Misdemeanor Name: Abrahamson, Ty Joseph Age: 48 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 10/24/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Trespass of Real Property Misdemeanor Name: Aden, Ahmed Omar Age: 35 City: State: Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 06/02/2016 485 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing TRAFF/ACC (EXC DUI) Misdemeanor Name: Adkins, Kyle Gabriel Age: 53 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/28/2013 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game Misdemeanor Name: Aguilar, Raul, JR Age: 32 City: Couderay State: WI Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 02/17/2016 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Driving Under the Influence Misdemeanor Name: Ainsworth, Kyle Robert Age: 27 City: Duluth State: MN Issued Date Bail Amount Warrant Type Charge Offense Level 11/22/2019 100 Bench Warrant-fail to appear at a hearing Theft Misdemeanor ST. -

Boston College Magazine

ALSO: RETIREMENT CRUNCH / WILLING SPIRIT LLEGE magazine t \\v i alt Grace Notes EXPERIENCING JOHN MAHONEY & 3 PROLOGUE Prospectors What would become Somerville, Jersey is to the New York City region, watched the bright swirl of dancers. It Massachusetts, was first settled so, did we discover, was our new home- is no coincidence that when Charles- by "Charles Sprague and his bretheren town to the Boston area: the morning town allowed itself to be annexed by [sic] Richard and William," late of Sa- DJ's surefire giggle starter; an easy mark Boston, Somerville stayed a stubbornly lem. They arrived in 1628, when for a lazy columnist on a slow news day. independent municipality. "Somerville" was a thickly wooded sec- We came not knowing any of this, A year after we landed, we bought a tion of Charlestown ripe for land pros- but we learned fast from the raised double-decker in whose backyard a pre- pectors like the Sprague boys. Just sh< >rt eyebrows and concerned looks we saw vious owner had planted another of three centuries later, cover subject on the faces of new acquaintances the double-decker. We stayed there 1 John Mahoney's family also came a- moment they learned where we had years. They were good years for us, and prospecting, part of the flood of refu- for Somerville. A new reform regime gees from Boston'steemingstreetswho Ifother towns were belles of had taken over City I lall. It was led by sought healthful air and lebensraum Mayor Gene Brune—a balding, middle- the bally Somerville was within streetcar commute of Boston's aged business manager, quiet as Calvin someone's stogie-chewing jobs. -

No Agent Rule"

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 61 Number 1 Article 1 2-1-2021 The Changing Landscape of Intercollegiate Athletics—The Need to Revisit the NCAA's "No Agent Rule" Sahl, John P. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation John P. Sahl, The Changing Landscape of Intercollegiate Athletics—The Need to Revisit the NCAA's "No Agent Rule," 61 SANTA CLARA L. REV. 1 (2020). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized editor of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE OF INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS—THE NEED TO REVISIT THE NCAA’S “NO AGENT RULE” John P. Sahl* The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), the primary governing body for intercollegiate athletics, promulgated its “No Agent Rule” in 1974 prohibiting advisors of student-athletes from communi- cating and negotiating with professional sports teams. As part of a core principle of amateurism, the NCAA adopted this rule, in part, to deline- ate between professional athletes and student athletes. However, through economic and societal evolution, this policy is antiquated and detrimental to the personal and professional development of college ath- letes. This Article argues in favor of expanding the recent Rice Commis- sion’s recommendation, adopted by the NCAA, to grant an exception from the No Agent Rule for Men’s Division I elite basketball players to all college sports and levels of competition. -

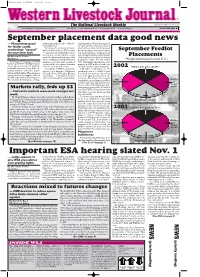

Important ESA Hearing Slated Nov. 1 — Judge Appears to Forest Service (USFS) and Feder- Tion of Habitat Deemed Necessary for Tiffs

02page1.qxd 10/24/02 5:00 PM Page 1 The National Livestock Weekly October 28, 2002 • Vol. 82, No. 02 “The Industry’s Largest Weekly Circulation” www.wlj.net • E-mail: [email protected] • [email protected] • [email protected] A Crow Publication September placement data good news — Placements good tember placements also added to ing September. While that figure is for feeder cattle, the bullishness. two percent more than last year, it In terms of near-term fed mar- was between four and 20 percent marketings “neutral” kets — late October and November below analysts’ pre-report expec- September Feedlot for near-term feds. — analysts said September mar- tations. In addition, the figure is al- keting data really didn’t create most 20 percent below the number Placements By Steven D. Vetter much of a price trend one way or the of cattle placed into feedlots during WLJ Editor other. Analysts also said delivery to September 2000. For the entire (Weight distribution for total U. S.) Reactions to USDA’s most recent packers over the next couple of U.S., September placements were Cattle-on-Feed (C-o-F) Report were, weeks will be a key price indicator pegged at 2.19 million head, also across the board, bullish, particu- over the next month or two. two percent more than last year. 2002 800 lbs. & heavier (23.08%) larly with the much lower-than-ex- According to USDA’s seven-state September marketings, for the pected number of feedlot place- report — for Arizona, California, seven-state report, totaled 1.57 mil- ments in September. -

Business People Who Died in 2010

Business people who died in 2010 January-2010 Harry Männil Born May 17, 1920(1920-05-17) Tallinn, Estonia Died January 11, 2010(2010-01-11) (aged 89) San José, Costa Rica Resting Costa Rica place Residence Estonia (1920–1943) Venezuela (1946–2010) Ethnicity Estonian Citizenship Estonian, Venezuelan Occupation Businessman Known for Entrepreneurship, art collecting, alleged war crimes Spouse Masula D'Empaire Children 4 Relatives Ralf Männil (brother) Harry Männil (May 17, 1920 Tallinn, Estonia – January 11, 2010 San José, Costa Rica) was an Estonian businessman, art collector, and cultural benefactor in several countries. In 1946, he moved to Venezuela, where he lived for the rest of his life. He was a successful businessman and part owner of ACO Group, a large Venezuelan automotive concern. He formed his own company in 1994. Harry Männil was accused by the Simon Wiesenthal Center of having participated in the murder of Jews while he worked for the political police in 1941–1942 during the German occupation of Estonia. After a four-year probe, Estonian investigators could find no evidence against him and he was cleared of the charges. Harry Männil was born into an iron salesman's family on May 17, 1920, in Tallinn, Estonia, and spent his childhood in Pääsküla, Tallinn. [1] [2] He graduated from the Gustav Adolf Grammar School in 1938 and from 1939–40 studied economics at the University of Tartu and the Tallinn University of Technology.[1] In the summer of 1941, during the Soviet occupation, he hid in a forest to avoid the mobilization.[1] Männil joined the political police of the Estonian Self-Administration as an assistant in September 1941. -

January 1958

0 F D E L T A S I G M A p I ~~f!JJ~ . {¥~ JANUARY 1958 * * FOUNDED 1907 * * The International Fraternity of Delta Sigma Pi Professional Commerce and Business Administration Fraternity Delta Sigma Pi was founded at New York Univer· sity, School of Commerce, Accounts and Finance, on November 7, 1907, by Alexander F. Makay, Alfred Moysello, Harold V. I acobs and H. Albert Tienken. Delta Sigma Pi is a professional frater nity organized to foster the study of business in universities; to encourage scholarship, social ac tivity and the association of students for their mu tual advancement by research and practice; to pro mote closer affiliation between the commercial world and students of commerce; and to further a high standard of commercial ethics and culture, and the civic and commercial welfare of the com munity. \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ IN THE PROFESSIONAL SPOTLIGHT THE DELTA SIGMA PI Chapter Delegate to the 62nd Annual Congress of American Industry of the National Association of Manufacturers, Fred W. Winter (left) of the University of Missouri is shown discussing his trip to New York City with the Faculty Advisors of Alpha Beta Chapter at Missouri, Frederick Everett (center) and Royal D. M. Bauer. Participation in this outstanding meeting of the N.A.M. is one of the annual professional highlights of Delta Sigma Pi. January 1958 Vol. XLVII, No. 2 0 F D E L T A s G M A p Editor From the Desk of The Grand President 34 J. D. THOMSON Some Chatter from The Central Office 34 Associate Editor Three New Chapters Swell Chapter Roll 35 }ANE LEHMAN Installation of Delta Iota at Florida Southern . -

AAB Annual Report 2018-19

Boston College Athletics Advisory Board Annual Report, 2018-19 This Report summarizes for the University community developments related to Boston College’s intercollegiate athletics program and the Athletics Advisory Board’s (AAB) activities during the past academic year. 1. Academic and Athletics Highlights A. ACC Academic Consortium The Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) sponsored its 14th year of initiatives organized By the ACC Academic Consortium (ACCAC). Boston College students, faculty, and administrators participated in ACCAC events held during both fall and spring semesters. The ACCAC leverages the athletics association and identity of the 15 ACC institutions in order to enrich their educational mission. This spring, the annual Meeting of the Minds conference, designed to showcase undergraduate research at memBer institutions, was held at the University of Louisville on March 29-31. Over 70 students from across the ACC, including four from Boston College, presented their work during the two-day event. The second annual ACC-Smithsonian ACCelerate Festival took place in Washington, DC. on April 5-7. Visitors to the Festival interacted with innovators and experienced new interdisciplinary technologies developed to address gloBal challenges. The event, which was programmed by Virginia Tech, featured 38 interactive installations from across the 15 ACC schools grouped by three thematic areas: exploring place and environment; exploring health, Body, and mind; and exploring culture and the arts. Visitors also viewed 15 dramatic and musical -

2013Viewbook Web.Pdf

Welcome to Emmanuel College. Emmanuel College is academic excellence in the Table of Contents liberal arts and sciences. The Emmanuel Learning Experience 2 Boston 3 It is commitment to mission and service to others. The Sciences 4 It is discovery through research, internships and global study. Research + Scholarship 6 It is community spirit on campus and beyond. Internships + Career Development 8 It is engagement with the vibrant and diverse city of Boston. Colleges of the Fenway 10 Study Abroad 11 It is a place to bring your all. A place to call your own. A place Start Here — Campus + Boston Map 12 where you can make a difference and discover your passion. Campus + Residence Life 14 Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur 16 Mission + Ministry 17 It is personal. Athletics 18 It is powerful. Leadership + Engagement 20 It is your next step. Alumni Network 22 Visit + Apply 24 Welcome to Emmanuel College. The Emmanuel Learning Experience A HANDS-ON APPROACH Here, every class is taught by a professor, not a teaching assistant, creating a deep, personal student-faculty relationship that begins on day one. With more than 50 areas of study to explore, our goal is to instill in you the knowledge, skills and habits of a mind developed through the study of the liberal arts and sciences. We are a community with a lifelong passion for teaching and learning, rooted in the commitment to rigorous intellectual inquiry and the pursuit of truth. We believe in an education shaped by the Catholic intellectual tradition — one that develops your academic potential, your sense of self and your commitment to serve others. -

Title Page Abstract and Table of Contents

REFLECTIONS ON GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY ATHLETICS: PAST, PRESENT, AND A PROPOSAL FOR THE FUTURE. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Michael J. Callahan, B.S.F.S Georgetown University Washington, D.C. March 28, 2012 REFLECTIONS ON GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY ATHLETICS: PAST, PRESENT, AND A PROPOSAL FOR THE FUTURE. Michael J. Callahan, B.S.F.S MALS Mentor: Shelly Habel, Ph.D ABSTRACT Intercollegiate Athletics Programs in America generally follow two models, “Competitive” Athletics and “Participatory” Athletics. “Competitive” athletic teams are well funded and capable of winning conference and NCAA championships. “Participatory” athletic teams are not well funded and are not expected to win. “Participatory” teams are centered around the idea of providing student-athletes an opportunity to compete in a sport they enjoy playing. Georgetown University, a member of the Big East Athletic Conference, is operating its Athletic Department using both the “Competitive” and “Participatory” models. Georgetown University’s marquee athletic program is Men’s Basketball and membership in the Big East Conference has proven to be very valuable for the team and the University. The exposure of the program and the University on national television broadcasts gives Georgetown a tremendous amount of publicity. Revenues from ticket sales and merchandising have also proven to be very lucrative. The Big East Conference is great for the game of basketball but the same cannot be said for all sports at Georgetown. -

2017-18 NCHC WEEKLY RELEASE National Collegiate Hockey Conference 1631 Mesa Avenue, Suite C Colorado Springs, CO 80906 Phone: 719-203-6818 Week of Oct

2017-18 NCHC WEEKLY RELEASE National Collegiate Hockey Conference 1631 Mesa Avenue, Suite C Colorado Springs, CO 80906 Phone: 719-203-6818 Week of Oct. 23-29, 2017 Fax: 719-645-8206 Volume 5, Issue 5 www.NCHCHockey.com Michael Weisman • O: 719-694-9924 • C: 513-310-4869 • [email protected] • @TheNCHC 2017-18 NCHC StaNdiNgS Conference Overall Pts. GP W L T 3/SW Win Pct. GF GA GP W L T Win Pct. GF GA 1. Colorado College 0 0 0 0 0 0/0 .000 0 0 6 4 2 0 .667 18 16 Denver 0 0 0 0 0 0/0 .000 0 0 4 2 0 2 .750 14 8 Miami 0 0 0 0 0 0/0 .000 0 0 4 1 3 0 .250 13 17 Minnesota Duluth 0 0 0 0 0 0/0 .000 0 0 6 2 2 2 .500 21 19 North Dakota 0 0 0 0 0 0/0 .000 0 0 6 4 1 1 .750 17 7 Omaha 0 0 0 0 0 0/0 .000 0 0 4 2 1 1 .625 15 12 St. Cloud State 0 0 0 0 0 0/0 .000 0 0 5 5 0 0 1.000 23 10 Western Michigan 0 0 0 0 0 0/0 .000 0 0 7 3 3 1 .500 22 18 Teams are awarded three points for each conference win in regulation or 5-on-5 overtime, and one point for a 5-on-5 overtime tie. Conference games still tied after a five-minute 5-on-5 overtime advance to a five-minute 3-on-3 overtime (and sudden victory shootout if still tied) with the team that wins the second overtime/shootout receiving an extra point in the standings (3/SW in the standings), making all games worth three points. -

Self-Guided Tour

WELCOME TO BOSTON COLLEGE This self-guided tour of the Chestnut Hill Campus highlights our Office of Undergraduate Admission facilities, from state-of-the-art Devlin 208 academic buildings to our iconic 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 athletic stadium and other Boston College treasures. 617–552–3100 • 800–360–2522 [email protected] bc.edu/admission Enjoy your time and thank you for visiting! To be added to our mailing list, please go to: bc.edu/inquire CONNECT A VISITOR’S GUIDE Social icon Circle Only use blue and/or white. For more details check out our Brand Guidelines. TO THE CHESTNUT HILL Produced by the Office of University Communications September 2018 CAMPUS GLENMOUNT RD. LAKE ST. ST. PETER FABER JESUIT COMMUNITY ST. CLEMENT’S LAKE ST. THEOLOGY AND MINISTRY LIBRARY DANCE STUDIO SIMBOLI LAKE ST. CADIGAN ALUMNI CENTER BRIGHTON LAKE ST. CAMPUS COMM. AVE. COMM. AVE. CONFERENCE CENTER MCMULLEN MUSEUM OF ART GREYCLIFF RESERVOIR APARTMENTS TO THE BOSTON COLLEGE "T" STOP MBTA GREEN LINE A DEVLIN HALL University radio station. CAMPANELLA WAY Nestled among the buildings of Middle Campus, Devlin Hall The Eagle’s Nest on the is the location of the Office of Undergraduate Admission, second level and Carney’s which hosts thousands of on the third are two main L COMMONWEALTH AVE. CORCORAN visitors for Eagle Eye Campus dining facilities. COMMONS Visits throughout the year. ROBSHAM THEATER It is also home to the art, E STOKES HALL MAIN art history, film, and earth Upon opening in 2013, GATE and environmental sciences Stokes Hall received an departments.