The Social Impact of the Irish Border

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tidy Towns Competition 2019

Tidy Towns Competition 2019 Adjudication Report Centre: Newtowngore - An Ref: 436 Dúcharraig County: Leitrim Mark: 276 Category: A Date(s): 21/06/2019 Maximum Mark Mark Mark Awarded 2018 Awarded 2019 Community – Your Planning and Involvement 60 42 43 Streetscape & Public Places 60 36 37 Green Spaces and Landscaping 60 34 35 Nature and Biodiversity in your Locality 50 20 21 Sustainability – Doing more with less 50 16 18 Tidiness and Litter Control 90 56 59 Residential Streets & Housing Areas 50 31 32 Approach Roads, Streets & Lanes 50 30 31 TOTAL MARK 470 265 276 Community – Your Planning and Involvement / An Pobal - Pleanáil agus Rannpháirtíocht: Cuireann an moltoir seo failte roimh Newtowngore (An Ducharraig) chuig Comortas na mBailte Slachtmhara Super Valu 2019. Thank you for your very informative and engaging entry form which was written in a story narrative format that proved easy to relate to but still informed us of all your activities under the relevant categories. The 5 year action plan which came into being in 2016 has been critical to the development of the village over the last three/four years and the adjudicator was able to measure what has been achieved in that period by seeing what was on the ground. Thank you also for the excellent map which was more than useful for the purposes of adjudication. It was the adjudicator’s first visit to the village and he was most impressed with the manner in which you as a committee engage with the local community. The committee of eight is certainly sufficient in numbers to administer the work load of Tidy Towns in the village. -

Leitrim Council

Development Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 County / City Council GIS X GIS Y Acorn Wood Drumshanbo Road Leitrim Village Leitrim Acres Cove Carrick Road (Drumhalwy TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Aigean Croith Duncarbry Tullaghan Leitrim Allenbrook R208 Drumshanbo Leitrim 597522 810404 Bothar Tighernan Attirory Carrick-on- Shannon Leitrim Bramble Hill Grovehill Mohill Leitrim Carraig Ard Lisnagat Carrick-on- Shannon Leitrim 593955 800956 Carraig Breac Carrick Road (Moneynure TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Canal View Leitrim Village Leitrim 595793 804983 Cluain Oir Leitrim TD Leitrim Village Leitrim Cnoc An Iuir Carrick Road (Moneynure TD) Drumshanbo Leitrim Cois Locha Calloughs Carrigallen Leitrim Cnoc Na Ri Mullaghnameely Fenagh Leitrim Corr A Bhile R280 Manorhamilton Road Killargue Leitrim 586279 831376 Corr Bui Ballinamore Road Aughnasheelin Leitrim Crannog Keshcarrigan TD Keshcarrigan Leitrim Cul Na Sraide Dromod Beg TD Dromod Leitrim Dun Carraig Ceibh Tullylannan TD Leitrim Village Leitrim Dun Na Bo Willowfield Road Ballinamore Leitrim Gleann Dara Tully Ballinamore Leitrim Glen Eoin N16 Enniskillen Road Manorhamilton Leitrim 589021 839300 Holland Drive Skreeny Manorhamilton Leitrim Lough Melvin Forest Park Kinlough TD Kinlough Leitrim Mac Oisin Place Dromod Beg TD Dromod Leitrim Mill View Park Mullyaster Newtowngore Leitrim Mountain View Drumshanbo Leitrim Oak Meadows Drumsna TD Drumsna Leitrim Oakfield Manor R280 Kinlough Leitrim 581272 855894 Plan Ref P00/631 Main Street Ballinamore Leitrim 612925 811602 Plan Ref P00/678 Derryhallagh TD Drumshanbo -

Terrorism Knows No Borders

TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS October 2019 his is a special initiative for SEFF to be associated with, it is one part of a three part overall Project which includes; the production of a Book and DVD Twhich captures the testimonies and experiences of well over 20 innocent victims and survivors of terrorism from across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland. The Project title; ‘Terrorism knows NO Borders’ aptly illustrates the broader point that we are seeking to make through our involvement in this work, namely that in the context of Northern Ireland terrorism and criminal violence was not curtailed to Northern Ireland alone but rather that individuals, families and communities experienced its’ impacts across the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and beyond these islands. This Memorial Quilt Project does not claim to represent the totality of lives lost across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland but rather seeks to provide some understanding of the sacrifices paid by communities, families and individuals who have been victimised by ‘Republican’ or ‘Loyalist’ terrorism. SEFF’s ethos means that we are not purely concerned with victims/survivors who live within south Fermanagh or indeed the broader County. -

Cross-Border Cooperation in Northwest Region

Centre for International Borders Research Papers produced as part of the project Mapping frontiers, plotting pathways: routes to North-South cooperation in a divided island IRISH CROSS-BORDER CO-OPERATION: THE CASE OF THE NORTHWEST REGION Alessia Cividin Project supported by the EU Programme for Peace and Reconciliation and administered by the Higher Education Authority, 2004-06 WORKING PAPER 14 IRISH CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION: THE CASE OF THE NORTHWEST REGION Alessia Cividin MFPP Working Papers No. 14, 2006 (also printed as IBIS working paper no. 64) © the author, 2006 Mapping Frontiers, Plotting Pathways Working Paper No. 14, 2006 (also printed as IBIS working paper no. 64) Institute for British-Irish Studies Institute of Governance ISSN 1649-0304 Geary Institute for the Social Sciences Centre for International Borders Research University College Dublin Queen’s University Belfast ABSTRACT BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION IRISH CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION: Alessia Cividin is a PhD candidate at the Planning Department, IUAV, University of THE CASE OF THE NORTHWEST REGION Venice. She holds a Bachelor of Architecture degree from the University of Venice, and was a visiting research associate at Queen’s University of Belfast in 2005 work- Traditionally grasped as a division, the border between the Republic of Ireland and ing on cross-border cooperation. Her research addresses the issues of cross-border Northern Ireland is increasingly understood as forming an individual unit made up of cooperation, regional governance and territorial planning, and links these to reason- multiple connections. This paper analyses this border as assumed, and tries to de- ing under intercultural communication. velop its meaning within a European setting. -

Cross-Border Population Accessibility and Regional Growth: an Irish Border Region Case-Study

9 200 Cross-Border Population September Accessibility and Regional Growth: – An Irish Border Region Case-Study 52 Declan Curran No Justin Gleeson NIRSA Working Paper Series Cross-Border Population Accessibility and Regional Growth: An Irish Border Region Case-Study Declan Curran1 Justin Gleeson National Institute for Regional and Spatial Analysis National University of Ireland Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare IRELAND [email protected] [email protected] September 2009 Abstract This paper calculates and maps relative population accessibility indices at a national and regional level for the island of Ireland over the period 1991-2002 and assesses whether the changing nature of the border between the Republic and Northern Ireland as it becomes more porous has impacted on the growth of the Irish border region over that time period. A spatial econometric analysis is the undertaken to assess the economic consequences of increased economic integration between Northern Ireland and the Republic. Neoclassical β-convergence regression analysis is employed, with the population accessibility indices used to capture the changing nature of the Irish border. 1 The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Irish Social Sciences Platform (ISSP), the International Centre for Cross Border Studies (ICLRD), and the All-Island Research Observatory (AIRO). The authors also wish to thank Morton O’Kelly for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper and Peter Foley for his excellent research assistance. 1 1. Introduction It is well known that many existing national borders have been shaped by the conflicts and post-war negotiations experienced throughout the 20th century and earlier. -

Monaghan County Development Plan 2019 - 2025

MONAGHAN COUNTY DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2019 - 2025 Comhairle Contae Mhuineacháin March 2019 Monaghan County Development Plan 2019-2025 Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction Section Section Name Page No. 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Plan Area 1 1.2 Plan Title 2 1.3 Legal Status 3 1.4 Challenges for County Monaghan 5 1.5 Content and Format 6 1.6 Preparation of the Draft Plan 6 1.7 Pre-Draft Consultation 6 1.8 Stakeholder Consultation 7 1.9 Chief Executive’s Report 7 1.10 Strategic Aim 7 1.11 Strategic Objectives 7 1.12 Policy Context 8 1.13 Strategic Environmental Assessment 15 1.14 Appropriate Assessment 16 1.15 County Profile 16 1.16 Population & Demography 17 1.17 County Monaghan Population Change 17 1.18 Cross Border Context 20 1.19 Economic Context 21 Chapter 2 Core Strategy Section Section Name Page No. 2.0 Introduction 23 2.1 Projected Population Growth 24 2.2 Economic Strategy 26 2.3 Settlement Hierarchy 27 2.3.1 Tier 1-Principal Town 27 2.3.2 Monaghan 28 2.3.3 Tier 2- Strategic Towns 29 2.3.4 Carrickmacross 30 2.3.5 Castleblayney 30 2.3.6 Tier 3 -Service Towns 30 2.3.7 Clones 31 2.3.8 Ballybay 31 i Monaghan County Development Plan 2019-2025 2.3.9 Tier 4 -Village Network 31 2.3.10 Tier 5 -Rural Community Settlements 32 2.3.11 Tier 6- Dispersed Rural Communities 32 2.4 Population Projections 33 2.4.1 Regeneration of Existing Lands 33 2.4.2 Housing Need Demand Assessment 2019-2039 35 2.5 Core Strategy Policy 37 2.6 Rural Settlement Strategy 39 2.7 Housing in Rural Settlements 41 2.7.1 Rural Settlement objectives and policies 42 2.8 Rural Area Types 44 2.8.1 Category 1 – Rural Areas Under Strong Urban Influence 45 2.8.2 Category 2 – Remaining Rural Area 47 2.9 Unfinished Housing in Rural Areas Under Strong Urban 47 Influence Chapter 3 Housing Section Section Name Page No. -

Buncrana Report

Strategic Strengths and Future Strategic Direction of Buncrana, County Donegal A Donegal County Council Commissioned Study August 2020 Cover Image: © Matthew Clifford of CE Óige Foróige Club, Buncrana ii The information and opinions expressed in this document have been compiled by the authors from sources believed to be reliable and in good faith. However, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. All opinions contained in this document constitute the authors judgement as of the date of publication and are subject to change without notice. iii Acknowledgements The ICLRD would like to thank Donegal County Council for their assistance, advice and guidance throughout the course of this study. We also convey our sincerest thanks to the numerous interviewees and focus group attendees who were consulted during the course of this research; the views and opinions expressed contributed significantly to this work. The research team takes this opportunity to thank the ICLRD partners for their support during this study, and Justin Gleeson of the All-Island Research Observatory (AIRO) for his assistance in the mapping of various datasets. iv Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Purpose of this Report ................................................................................................................ -

Brexit at the Border: Voices of Local Communities in the Central Border Region of Ireland/Northern Ireland

Brexit at the Border: Voices of local communities in the Central Border Region of Ireland/Northern Ireland Hayward, K. (2018). Brexit at the Border: Voices of local communities in the Central Border Region of Ireland/Northern Ireland. Irish Central Border Area Network. Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2018 The Author. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 BREXIT AT THE BORDER: Voices of Local Communities in the Central Border Region of Ireland / Northern Ireland Executive Summary B 3 O 1 A 1 B 3 R 1 E 1 X 8 I 1 T 1 D 2 T 1 H 4 E 1 R 1 BREXIT AT THE BORDER Voices of Local Communities in the Central Border Region of Ireland / Northern Ireland A report prepared for the Irish Central Border Area Network By Katy Hayward Centre for International Borders Research Queen’s University Belfast Belfast June 2018 ISBN 978-1-909131-69-9 Boarding on Brexit Contents Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................... -

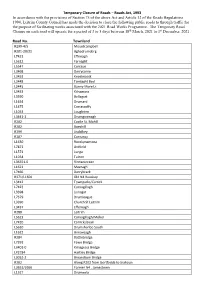

Temporary Closure of Roads

Temporary Closure of Roads – Roads Act, 1993 In accordance with the provisions of Section 75 of the above Act and Article 12 of the Roads Regulations 1994, Leitrim County Council has made the decision to close the following public roads to through traffic for the purpose of facilitating works associated with the 2021 Road Works Programme. The Temporary Road Closure on each road will operate for a period of 3 to 5 days between 18th March, 2021 to 1st December, 2021. Road No. Townland R299-4/5 Mountcampbell R201-20/21 Aghadrumderg L7421 Effrinagh L5612 Farnaght L5547 Curraun L3468 Derrycarne L3453 Knockroosk L3448 Tamlaght Bed L3445 Bunny More Lr. L3433 Kilnagross L3390 Bellagart L1624 Drumard L1475 Corrascoffy L1053 Loughrinn L3441-1 Drumgownagh R202 Castle St. Mohill R202 Boeshill R299 Lisdalkey R207 Cornaroy L1630 Rooskynamona L7471 Antfield L1571 Lunga L1054 Tulcon L36551-0 Rinnacurreen L1621 Meeragh L7466 Derrybrack R371/L1601 Old N4 Rooskey L3412 Townparks/Carrick L7423 Cornagillagh L3398 Lisnagat L7379 Drumleague L3390 Church St Leitrim L3437 Effernagh R280 Leitrim L5623 Cornagillagh/Moher L7420 Carrickslavan L5610 Drumshanbo South L1622 Annaveagh R284 Battlebridge L7391 Fawn Bridge L3401-0 Kilnagross Bridge LP2784 Hartley Bridge L3052-2 Breandrum Bridge R202 Along R202 from Gortfadda to Srahaun L3651/2656 Former N4 , Jamestown L1527 Drumeela L1589 Gortermone L5581 Aghakiltubid L1312 Stradermot L5668 Lough Sallagh L5598 Gulladoo L1574-3 Fearglass North L4294 Annagh Upper L3302 Greaghnagullion L3356 Drumaweel Glebe L1343 Clogher L5662 -

Leitrim County Council Dangerous Substances 2006

LEITRIM COUNTY COUNCIL DANGEROUS SUBSTANCES 2006 IMPLEMENTATION REPORT For inspection purposes only. Consent of copyright owner required for any other use. Water Quality (Dangerous Substances) Regulations, 2001 S.I. 12 of 2001 EPA Export 26-07-2013:02:40:02 SECTION 1 CURRENT WATER QUALITY STATUS AND TARGETS 1.1 Existing Condition In the EPA survey of Dangerous Substances in Surface Freshwaters 1999-2000, there are 5 sites in County Leitrim. Site no. 40 Lough Allen S.E. Drummans Island Site no. 41 Lough Allen N.W. Drumshambo Site no. 43 0.5 km d/s Carrick on Shannon Site no. 44 Rail bridge d/s Masonite Site no. 45 D/s Roosky Atrazine, Simazine, Toluene, Xylenes, Arsenic, Chromium, Copper, Lead, Nickel and Zinc were analysed. All 5 sites complied with the standards as set out in the Regulations. Dichloromethane, Cyanide and Fluoride were not included in the EPA survey. The River Shannon was monitored at Carrick on Shannon upstream of the town on 1 occasion in 2005 as part of the EU (Quality of Surface Water Intended for the Abstraction of Drinking Water) Regulations, 1989. Lough Gill was monitored at the intake point for the North Leitrim Regional Water Supply Scheme under the above Regulation also in 2005. Surface water at the landfills at Mohill and Carrick on Shannon were analysed for dangerous substances as part of the Waste Licence issued by the EPA for these facilities. For inspection purposes only. Monitoring for dangerous substancesConsent of copyright was owner carri requireded out for any at other 14 use. No sites on rivers in Co. -

Letterkenny Brochure

COUNTY DONEGAL LETTERKENNY IRELAND County Donegal’s Gateway Town for Business, Commerce & Industry comhairle chontae dhún na ngall donegal county council Letterkenny - County Donegal’s Gateway Town for Business, Commerce & Industry Letterkenny Leitir Ceanainn - Gateway to the 21st Century Letterkenny, the commercial centre of Co. Donegal, is a modern vibrant town with a rich cultural heritage. As well as being County Donegal’s largest town, Letterkenny is also the largest town in the three Ulster counties within the Republic of Ireland, with a population last year of 19,588. Nationally, the figures show an increase in Ireland’s population density, with an average of 67 people living on every square kilometer – compared to 62 in the previous census of 2006. In 2002 under the auspices of the Irish Government’s National Spatial Strategy Letterkenny was designated a Linked Gateway along with the City of Derry. Originally a market town serving a wide agricultural hinterland, Letterkenny has evolved to become a modern centre for industry and enterprise. The town has a long track record of adaptability. Expanding from a market town, it made use of its location on the shores of Lough Swilly to become a thriving port during the 19th Century. In the latter part of the 19th and early part of the 20th Century the railway age impacted on Letterkenny, connecting it with outlying towns in North and West Donegal. Despite the closure of the railway in the 1950’s, improving road communications ensured that Letterkenny stayed at the centre of the economic development of Co. Donegal. Letterkenny provided a setting for new industries and service sector enterprises when the traditional industries of agriculture and textiles declined. -

The Border Regional Authority

The Border Regional Authority Údarás Réigiúnach na Teorann Draft Regional Planning Guidelines (2010-2022) January 2010 DRAFT REGIONAL PLANNING GUIDELINES FOR THE BORDER REGION 2010 – 2022 Planning & Development Acts 2000-2006 Planning & Development Regulations 2001 - 2009 Planning & Development (Regional Planning Guidelines) Regulations 2009 Planning & Development (Strategic Environmental Assessment) Regulations 2004 Public Consultation Period 26th February, 2010 – 14th May, 2010. In accordance with Section 24(4) of the Planning & Development Acts 2000-2006, the Border Regional Authority hereby gives notice that it has prepared Draft Regional Planning Guidelines for the Border Region 2010 - 2022. The Draft has been prepared in accordance with the Planning & Development Acts 2000-2006, the Planning & Development (Regional Planning Guidelines) Regulations 2009 and the Planning & Development (Strategic Environmental Assessment) Regulations 2004. The Constituent Counties in the Border Region are Cavan, Donegal, Leitrim, Louth, Monaghan and Sligo. The objective of the Regional Planning Guidelines is to provide a long-term strategic planning framework for the future physical, economic and social development of the Region and shall in accordance with the Act, be incorporated into the County Development Plans of the respective Planning Authorities in the Region. The Draft Guidelines are supported by a Draft Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Environmental Report, on the likely significant effects on the environment of implementing the Guidelines, and a Draft Habitats Directive Assessment (HDA) in accordance with Article 6 of EU Directive 92/43/EEC. Individuals, Public Authorities, Community Organisations, Public and Private Agencies, and any other group are invited to make submissions/observations with respect to the Draft Regional Planning Guidelines, Draft SEA Environmental Report, and Draft Habitats Directive Assessment.