Third International Workshop on Sustainable Land Use Planning 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open As a Single Document

ARNOLD ARBORETUM HARVARD UNIVERSITY ARNOLDIA A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION VOLUME XXIII 19633 , PUBLISHED BY THE ARNOLD ARBORETUM JAMAICA PLAIN, MASSACHUSETTS ARNOLDIA A continuation of the ’ BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME 23 JANUARY 18, 1963 NuMe~;a 1 TRIAL PLOT FOR STREET TREES the spring of 1951 a trial plot of eighty small ornamental trees was plantedDI~ RING on the Case Estates of the Arnold Arboretum in Weston (see .9rnoldia 16: (B~ 9-1.5, 1906~. A few of these were not happy in their location and promptly died, or did so poorly as to warrant their removal. A few new varie- ties were added to the original group, but for the most part these trees have been growing there s~nce the trial plot was first laid out. The collection has been of special interest to home owners in the suburban areas of Boston, who naturally are interested in small ornamental trees. It has also been of considerable interest to the tree wardens of various towns throughout New England, for here one may see many of the best small trees growing side by side, so that comparisons can be easily made. Recently this plot has been of interest to the Electric Council of New England, a group of utility companies which provide various electric services for the public in addition to stringing electric lines for these services. When the right kinds of trees are planted properly in the right places along the streets and highways, there need be but little competition between the trees and the wires. -

No. 56. P E R S O N a L Ideas About the Application of the International

Mededeelingen 's Rijks Herbarium Leiden No. 56. Personal ideas about the application of theInternationa l Ruleso f Nomenclature, or, as with the Rules themselves, Inter national deliberation? II. Some denominations of Dicotyledonous Trees and Shrubs species. With a Retrospection and a set of Propositions on the Nomenclature-Rules BY Dr. J. VALCKENIER SÜRINGAR, retired prof, of the Agricultural Academy in the Netherlands. INTRODUCTION. This second Part has its origin principally in Dr. ALFRED REHDER'S "Manual of Cultivated Trees and Shrubs" 1927. That admirable work contains several revolutionary looking changes of names, which changes partly were already propagated in BAILEY'S works of the last years; and I have made a study of those names, beside others. The result is that I cannot in many cases join with REHDER'S new-old names and principles. But when I therefore criticise in all those cases REHDER'S opinion, the reader must not think thereby that I criticise REHDER'S work as a whole. I criticise the names and principles only because I think that these changes and principles are unfavourable with respect to the world's effort to obtain unity of plantnomenclature; and I don't think about criticizing the work as a whole. REHDER'S "Manual" is the result of long and arduous work; it is in its relative size the most complete, the sharpest as to the characters, the newest and most usable of all Dendrological works existing. No Dendrologist, even no Botanist, who has to do with Trees and Shrubs, can do without it. Readers, who wish eventually to obtain corrigenda and addenda to this paper or to the first part of it, are requested to communicate with the writer, who will be moreover thankful for hints and observations. -

Charles Sprague Sargent

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XII SEVENTH MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF CHARLES SPRAGUE SARGENT BY WILLIAM TRELEASE PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1928 CHARLES SPRAGUE SARGENT April 24, 1841—March 22, 1927 BY WILLIAM "One day," said Edward Everett Hale, "a man looked up— and saw a tree." He was speaking of our late associate, Charles Sprague Sargent: director of the first forest census of the United States; gatherer of a great museum exposition of our trees; author of the first comprehensive treatise on our woods and their proper- ties and uses, of a compact and workable handbook of our native trees, and of a sumptuously published Silva of North America; founder and editor of a journal, Garden and Forest, which did much to promote love of the out-of-doors; stimulator of a national forest-preserve and park system; and creator and utilizer of the greatest of tree plantations:—the foremost den- drologist of his day. Sargent was of good and efficient English ancestry domiciled in New England for over three centuries; he was related to John Singer Sargent who in the field of art rivals Charles Sprague in that of science. He was the son of Ignatius Sargent, a suc- cessful merchant, and his life was spent on the beautiful estate Holm Lea, in Brookline, immediately adjoining his father's; within a stone's throw of the home of Francis Parkman, and in relation with many men who made Boston and its environs notable in the Victorian period. -

Open PDF File, 704.28 KB, for Citizen Forester September 2016

SEPTEMBER 2016 N O . 1 9 4 Pollinators in the Landscape III: Creating and Maintaining Pollinator Landscapes By Rick Harper and Our understanding of the urban for- created habitats Amanda Bayer est doesn't have to be just limited to might be necessary. its trees. In a broader sense, the urban ecosystem in- Bundled hollow cludes a variety of habitats, including public open spaces/ stems, bamboo, or grounds, greenways, rain gardens, and a plethora of pri- reeds are good for vate landscapes. Hence, those of us who manage these cavity-nesting bees. sites need to be aware of the different elements that Logs and stumps comprise these spaces, in order to manage them in ac- with beetle tunnels cordance with specific objectives. can be added to the landscape for cavity Pollinator-friendly plants are just one part of creating and -nesting bees, along maintaining pollinator-friendly landscapes. The creation with nesting blocks. of pollinator habitats incorporates design, cultural prac- When placing tices, pest management, and weed management strate- potential habitat Silver-spotted skipper on Malus sp., Johnny Apple- gies. Pollen, nectar, water, forage plants, nesting areas, objects in the seed Orchard, Springfield, MA. Photo: Mollie and shelter should all be considered during the design landscape, wind Freilicher process. Be creative, and don’t forget to think both big protection and sun and small – pollinators can be supported in a variety of exposure are ways, from trees that provide shelter and nesting materi- important considerations. Shade and part shade areas are als, to annuals planted in a window box for nectar and important, along with sunny areas, as they provide pollen. -

III EHW Ernest Henry Wilson (1876-1930)

III EHW Ernest Henry Wilson (1876-1930) papers, 1896-2017: Guide. The Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University © 2020 President and Fellows of Harvard College Ernest Henry Wilson (1876-1930) papers, 1896-2017: Guide. Archives of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 © 2012 President and Fellows of Harvard College Descriptive Summary Repository: Arnold Arboretum, Jamaica Plain, MA Call No.: III EHW Location: Archives. Title: Ernest Henry Wilson (1876-1930) papers, 1896-2017. Dates: 1896-1952. Creator: Wilson, Ernest Henry, 1876-1930. Quantity: 20 linear feet, 30 boxes Abstract: The Ernest Henry Wilson papers reflect his contribution to horticulture and botany as a plant collector who, through numerous expeditions to China, Korea, and Japan, introduced many new species into cultivation in arboreta, parks, and private gardens. The collection includes his extensive correspondence written between 1899 and 1930 to Arnold Arboretum staff, mainly Charles Sprague Sargent (1841-1927), the Arboretum's first director; copies of his letters to other Arboretum explorers and colleagues such as Joseph Charles Francis Rock (1884-1962), David Fairchild (1869- 1954), Frank Nicholas Meyer (1875-1918) Alfred Rehder (1863-1949), and members of the Veitch Nurseries in England. Other material includes field and plant collection notes, diaries, account books, shipping lists, maps, and manuscripts of both published and unpublished works. There are Chinese and other travel documents, letters of recommendation, certificates and material relating to Wilson's life as a student and his early work as a gardener. There is an extensive collection of clippings from newspapers and copies of articles from botanical and horticultural journals. -

Botanical Gardens, Public Space and Conservation

GROWING GARDENS: BOTANICAL GARADENS, PUBLIC SPACE AND CONSERVATION A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Terra Celeste Colburn June 2012 © 2012 Terra Celeste Colburn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP ii TITLE: Growing Gardens: Botanical Gardens, Public Space and Conservation AUTHOR: Terra Celeste Colburn DATE SUBMITTED: June 2012 COMMITTEE CHAIR: Dr. Matthew Hopper, Assistant Professor COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Joel Orth, Assistant Professor COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Matt Ritter, Associate Professor iii ABSTRACT Botanical Gardens in the Twentieth Century: Advent of the Public Space Terra Celeste Colburn This thesis examines the history of botanical gardens and their evolution from ancient spaces to the modern gardens of the 20th century. I provide a brief overview of botanical gardens, with a focus on the unique intersection of public participation and scientific study that started to occur within garden spaces during the 20th century, which still continues today. I reveal the history of gardens that influenced the uses of gardens today, with a focus on: the first ancient gardens and the dependency societies had on them, the influence of science in gardens starting in the Enlightenment period, the shift away from scientific gardens and the introductions of public gardens in the early 20th century, and the reintroduction of science into gardens during the conservation movement of the 1950s. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to Dr. Joel Orth for providing guidance, direction and encouragement on this thesis and to Garrett Colburn for editing multiple drafts. -

Seven-Son Flower from Zhejiang: Introducing the Versatile Ornamental Shrub Heptacodium Jasminoides Airy Shaw Gary L

Seven-Son Flower from Zhejiang: Introducing the Versatile Ornamental Shrub Heptacodium jasminoides Airy Shaw Gary L. Koller This fall, the Arnold Arboretum will begin distributing seedlings and rooted cuttings of a splendid new shrub from China In 1916, Alfred Rehder of the Arnold Arbor- miconioides because, he wrote, "In its habit etum described a new genus of shrub in the and general appearance this plant suggests a pages of Plantae Wilsonianae, the hefty, member of the family of Melastom[at]aceae three-volume "enumeration of the dried plants and on account of the comparatively small collected by Mr. E. H. Wilson during his flowers in terminal panicles it resembles par- expeditions to western China in behalf of the ticularly Miconia. Only close examination," Arnold Arboretum." Dubbed Heptacodium he continued, "showed that this interesting "in allusion to the seven-flowered heads of plant belongs to the Caprifoliaceae." It is the inflorescence" (from the Greek e~za, interesting to note that Wilson collected seven, and xw8e~a, a poppyhead), the genus Magnolia biondii near the same site, but at was assigned to the Caprifoliaceae, the family an elevation of six hundred meters (above two to which Lonicera (the honeysuckles) and thousand feet). Magnolia biondii recently Abelia belong. Translated, the plant’s Chinese was introduced to North America through name means "seven-son flower from Zhe- the efforts of the Arnold Arboretum. jiang." The next reference to the genus Hepta- Wilson collected the plant at Hsing-shan codium did not occur until thirty-three years in western Hupeh (Hubei) province, China later, in 1952, when Henry Kenneth Airy (Collection Number 2232). -

Latin for Gardeners: Over 3,000 Plant Names Explained and Explored

L ATIN for GARDENERS ACANTHUS bear’s breeches Lorraine Harrison is the author of several books, including Inspiring Sussex Gardeners, The Shaker Book of the Garden, How to Read Gardens, and A Potted History of Vegetables: A Kitchen Cornucopia. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 © 2012 Quid Publishing Conceived, designed and produced by Quid Publishing Level 4, Sheridan House 114 Western Road Hove BN3 1DD England Designed by Lindsey Johns All rights reserved. Published 2012. Printed in China 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-00919-3 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-00922-3 (e-book) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Harrison, Lorraine. Latin for gardeners : over 3,000 plant names explained and explored / Lorraine Harrison. pages ; cm ISBN 978-0-226-00919-3 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN (invalid) 978-0-226-00922-3 (e-book) 1. Latin language—Etymology—Names—Dictionaries. 2. Latin language—Technical Latin—Dictionaries. 3. Plants—Nomenclature—Dictionaries—Latin. 4. Plants—History. I. Title. PA2387.H37 2012 580.1’4—dc23 2012020837 ∞ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). L ATIN for GARDENERS Over 3,000 Plant Names Explained and Explored LORRAINE HARRISON The University of Chicago Press Contents Preface 6 How to Use This Book 8 A Short History of Botanical Latin 9 Jasminum, Botanical Latin for Beginners 10 jasmine (p. 116) An Introduction to the A–Z Listings 13 THE A-Z LISTINGS OF LatIN PlaNT NAMES A from a- to azureus 14 B from babylonicus to byzantinus 37 C from cacaliifolius to cytisoides 45 D from dactyliferus to dyerianum 69 E from e- to eyriesii 79 F from fabaceus to futilis 85 G from gaditanus to gymnocarpus 94 H from haastii to hystrix 102 I from ibericus to ixocarpus 109 J from jacobaeus to juvenilis 115 K from kamtschaticus to kurdicus 117 L from labiatus to lysimachioides 118 Tropaeolum majus, M from macedonicus to myrtifolius 129 nasturtium (p. -

Download Forsythia-Collection-Plan-2018

125 Arborway Boston, MA 02130-3500 tel: 617.524.1718 fax: 617.524.1418 www.arboretum.harvard.edu Forsythia Collection Development Plan - 2018 This document is a concise resource considering the background, current status, and future development goals of the Forsythia Collection at the Arnold Arboretum. A bibliography of the references used and appendices covering collections representation (Appendix 1), landscape locations (Appendix 2), taxonomy (Appendix 3), and cultivation (Appendix 4) are also included. Mission Statement The Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University discovers and disseminates knowledge of the plant kingdom to foster greater understanding, appreciation, and stewardship of Earth’s botanical diversity and its essential value to mankind. The Collection The Forsythia Collection at the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University contains the most comprehensive representation of species, and historic taxa developed and/or introduced into United States cultivation by the Arboretum. The collection was developed largely by C.S. Sargent and E.H. Wilson who, through expeditions, collected and introduced new species and cultivated forms; and by Dr. Karl Sax and this students who developed new hybrids at the Arnold Arboretum. Some of these historical taxa include: Forsythia ovata introduced by Wilson from Korea, a chance F. x intermedia seedling discovered by Dr. Alfred Rehder who named it ‘Primulina’, and iconic hybrids F. ‘Arnold Dwarf’, F. ‘Arnold Giant’, and F. ‘Karl Sax’ developed by Dr. Karl Sax. The richness of the Forsythia Collection at the Arnold Arboretum ensures that the diversity of Forsythia and its long horticultural history will not be forgotten. Collection Objectives To further develop and improve upon the current collection of Forsythia so that the Arnold Arboretum will continue to hold the most comprehensive wild origin collection of species and Arboretum historic introductions. -

American Magazine

The American HORTICULTURAL Magazine fall 1971 I volume 50 / number 4 50th Anniversary Edition Journal of the American Horticultural Society, Inc. 901 NORTH WASHINGTON STREET, ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA 22314 For United Horticulture . .. TELEPHONE 703-683-3077 The particular objects and business of the American Horticultural Society are to promote and encourage national in-terest in scientific research and education in horticulture in all of its branches. 1971-72 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE (to) President Treasurer DR. DAVID G. LEACH (1972) DR. GILBERT S. DANIELS (1972) 1674 Trinity Road Director North Madison, Ohio 44057 Hunt Botanical Library Carnegie-Mellon University First Vice President Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213 MRS. ERNESTA D. BALLARD (1973) Director, Pennsylvania Member of the Board Horticultural Society DR. HENRY M. CATHEY (1973) 325 Walnut Street Leader, Ornamental Investigations Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19106 Agricultural Research Service Second Vice President U.S. Department of Agriculture Beltsville, Maryland 20705 MR. FREDERICK J. CLOSE (1972) 6189 Shore Drive Immediate Past President North Madison, Ohio 44057 MR. FRED C. GALLE (1972) (*) Secretary Director of Horticulture DR. GEORGE H. M. LAWRENCE (1972) Callaway Gardens 390 Forge Road Pine Mountain, Georgia 31822 East Greenwich, Rhode Island 02818 AHS PLANT RECORDS CENTER MR. O. KEISTER EVANS MR. ROBERT D .• MACDONALD MR. RICHARD A. BROWN Executive Director Director Assistant Director Alexandria, Virginia Lima, Pennsylvania Lima, Pennsylvania (.) Members of the 1971·72 Board of Directors per bylaw provision. ( ..) Ex officio, and without vote. THE AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL MAGAZINE is the official publication of The American Horticultural Society and is issued during the Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall quarters. The magazine is included as a benefit of membership in The American Horticultural Society, individual membership dues being $15.00 a year. -

Johnston, I. M. 1935

JOURNAL OF THE ARNOLD ARBORETUM HARVARD UNIVERSITY ALFRED REHDER JOSEPH H. FAULL AND CLARENCE E. KOBUSKI VOLUME XVI Reprinted with the permission of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University KRAUS REPRINT CORPORATION New York '968 DATES OF ISSUE No. 1, (pp. 1-143, pi. 119-128) issued January 25, 1935. No. 2, (pp. 145-271, pi. 129-139) issued April 24, 1935. No. 3, (pp. 273-365, pi. 140-154) issued July 10, 1935. No. 4, (pp. 367-483, pi. 155-165) issued October 25, 1935. Printed in U.S.A. TABLE OF CONTENTS STUDIES IN BoRAGINACEAE, X. THK BOR AGI X AC'K A K OF NORTHEASTERN SOUTH AMERICA. By /z/a» M. Johnston 1 HAXDELIODENDRON. A NEW (kxus OF SAPINDACEAE. With plate 119 and one text figure. By Alfred Rehder 65 Noil's ox SOME OF THE FUEXACEAE AMI VERBEXACEAE OF TIIK SOLO- MON ISLANDS COLLECTED ON THE ARNOLD ARBORETUM EXPEDITION, 1930-1932. With plates 120-122. By R. C. Bakhuizcn van den Brink 68 Ax ENDEMIC SOPHORA FROM RUMANIA. With plates 123 and 124 and one text figure. By Edgar Anderson 76 TUM. By Ernest J. rainier 81 THE HOSTS OF GYMNOSPORAXOUM GLOBOSUM FARE, AND THEIR RELA- TIVE SUSCEPTIBILITY. With plates 125-128 and four text figures. By /. L. MacLachlan 98 A PRELIMINARY NOTE ON LIFE HISTORY STUDIES OF EUROPEAN SPECIES OF MII.ESIA. By Lillian M. Hunter 143 STUDIES IN THE BORAGINACEAE, XI. By Iran M. Johnston 145 LORANTHACEAE COLLECTED IN THE SOLOMON ISLANDS BY L. J. BRASS AND S. F. KAJEWSKI ON THE ARNOLD ARBORETUM EXPEDITION, 1930-1932. -

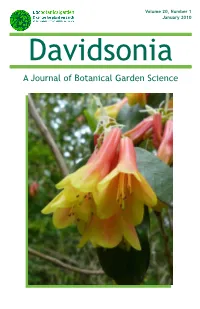

Davidsonia a Journal of Botanical Garden Science Davidsonia Editor Iain E.P

Volume 20, Number 1 January 2010 Davidsonia A Journal of Botanical Garden Science Davidsonia Editor Iain E.P. Taylor UBC Botanical Garden and Centre for Plant Research University of British Columbia 6804 Southwest Marine Drive Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, V6T 1Z4 Editorial Advisory Board Quentin Cronk Fred R. Ganders Daniel J. Hinkley Carolyn Jones Lyn Noble Murray Isman David Tarrant Roy L. Taylor Nancy J. Turner Kathy McClean Associate Editors Mary Berbee (Mycology/Bryology) Moya Drummond (Copy) Aleteia Greenwood (Art) Michael Hawkes (Systematics) Richard Hebda (Systematics) Douglas Justice (Systematics and Horticulture) Eric La Fountaine (Publication) Jim Pojar (Systematics) Andrew Riseman (Horticulture) Charles Sale (Finance) Janet R. Stein Taylor (Phycology) Sylvia Taylor (Copy) Roy Turkington (Ecology) Jeannette Whitton (Systematics) Davidsonia is published quarterly by the Botanical Garden of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 1Z4. Annual subscription, CDN$48.00. Single numbers, $15.00. All information concerning subscriptions should be addressed to the editor. Potential contributors are invited to submit articles and/or illustrative material for review by the Editorial Board. Web site: http://www.davidsonia.org/ ISSN 0045-09739 Cover: Pendulous blooms of Rhododendron cinnabarinum var. cinnabarinum Photo: Douglas Justice Back Cover: Plate from Flora Japonica, Sectio Prima, Philipp Franz von Siebold and Joseph Gerhard Zuccarini Image: Public Domain, courtesy of PlantExplorers.com Table of contents Editorial 1 Taylor Rhododendrons at UBC Botanical Garden 3 Justice Botanical history through 21 the names of paths, trails and beds in the University of British Columbia Botanical Garden: a case study Taylor and Justice Davidsonia 20:1 1 Editorial Collections Davidsonia is emerging from its second hiatus, the second in its 40 year history.