Untangling the Twisted Tale of Oriental Bittersweet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Field Release of the Leaf-Feeding Moth, Hypena Opulenta (Christoph)

United States Department of Field release of the leaf-feeding Agriculture moth, Hypena opulenta Marketing and Regulatory (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Programs Noctuidae), for classical Animal and Plant Health Inspection biological control of swallow- Service worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Field release of the leaf-feeding moth, Hypena opulenta (Christoph) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), for classical biological control of swallow-worts, Vincetoxicum nigrum (L.) Moench and V. rossicum (Kleopow) Barbarich (Gentianales: Apocynaceae), in the contiguous United States. Final Environmental Assessment, August 2017 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. -

Junker's Nursery

1 JUNKER’S NURSERY LTD 2011-2012 Higher Cobhay (01823) 400075 Milverton Somerset E-mail: [email protected] TA4 1NJ Website: www.junker.co.uk See website for more detail: www.junker.co.uk elcome to a new look catalogue. Mind you, the catalogue is season, but if that means planting at a time of year when the plants have2 the least of the changes this year! We have finally completed best chance of success, then that can only be a good thing. I would en- W our relocation to our new site. Although we have owned it courage you therefore to make your plans and reserve your plants for for nearly 4 years now, personal circumstances intervened and it has when we can lift them. Typically we start this in mid-October. The taken longer to complete the move than we anticipated. It was definitely plants don’t need to have completely lost their leaves, but they do need worth the wait though (even if the rain is streaming down the windows to have finished active growth for the season. We will then continue lift- yet again, even as I write this in late July!) So much is different that it’s ing right through until March or so, but late planting can be risky in the difficult to know where to start...what remains unchanged however is our event of a dry spring such as we’ve had the last couple of years. Lifting commitment to growing the most exciting plants to the best of our abil- is weather dependant though, as we can’t continue if everything is water- ity, and to giving you, the customer, the kind of personal service that logged or frozen solid. -

STACHYURUS- Staartaar Dendraflora Nr 33 - 1996

STACHYURUS- Staartaar Dendraflora Nr 33 - 1996 R.T. H_OUTMAN Een van de geslachten waar niet direct aan wordt gedacht, als het gaat om winterbloeiende gewassen, is Stachyurus. Deze tamelijk onbekende plant kan in de toekomst tot het standaardsortiment boomkwekerijgewassen behoren. Er is een toenemende vraag naar een breder sortiment met andere sierwaarden dan bloei in het voorjaar of de zomer; Stachyurus past hier zeer goed in. SYSTEMATIEK Stachyurus is een klein geslacht, dat in de familie van de Stachyuraceae is geplaatst. Over de classificatie van deze familie zijn de systematici het niet geheel eens, maar nadat de Stachyuraceae voorheen bij de Theaceae waren ondergebracht, wordt de familie nu als op zichzelf staand beschouwd binnen de orde van de Violales. Ook worden argumenten voor verwantschap met de Flacourtiaceae aangevoerd. Stachyurus bevat acht tot tien soorten, afhankelijk van de interpretatie, die de verschillende systematici hanteren. In Nederland zijn drie soorten in cultuur. Naast S. chinensis en S. praecox, wordt ook S. himalaicus op zeer beperkte schaal gekweekt. Over de kenmerken van de laatstgenoem de soort bestaat enige verwarring, hierover meer bij de soortsbeschrijving. MORFOLOGIE De tot Stachyurus behorende soorten zijn eenhuizige bladverliezende of groenblijvende struiken tot kleine bomen met verspreide bladstand. De enkelvoudige bladeren hebben gewoonlijk een gezaagde bladrand. De bloeiwijze is een okselstandige, hangende tros, die bestaat uit een aantal bloemen. Ze worden in het najaar gevormd. De afzonderlijke bloemen en vooral de vruchten zijn zeer kort gesteeld. Hieruit blijkt, dat - morfologisch gezien - de bloemen in een tros en dus niet in een aar bijeen staan. (De Nederlandse naam staartaar is daarom feitelijk onjuist). -

Taming the Wild Stewartia©

1 Boland-Tim-2019B-Taming-Stewartia Taming the Wild Stewartia© Timothy M. Boland and Todd J. Rounsaville Polly Hill Arboretum, 809 State Road, West Tisbury, Massachusetts 02575, USA [email protected] Keywords: Asexual propagation, native trees, plant collections, seeds, Stewartia SUMMARY The Polly Hill Arboretum (PHA) began working with native stewartia in 1967. Our founder, Polly Hill, was devoted to growing trees from seed. In 2006, the Polly Hill Arboretum was recognized as the Nationally Accredited Collection holder for stewartia. This status has guided our collection development, particularly on focused seed expeditions, which began in 2007. The PHA has been successful growing both species from seed, however, overwintering survival and transplanting of juvenile plants has proved more challenging. New insights into winter storage of seedlings is beginning to shed light on this problem. Experimentation with overwintering rooted cuttings has revealed that plants have preferred temperature and chilling requirements. These new overwintering protocols have thus far yielded positive results. Recent work with tissue culture has also shown promising results with both species. Future work includes grafting superior clones of our native stewartia onto Asiatic species in an effort to overcome the problematic issues of overwintering, transplantability, and better resistance to soil borne pathogens. Our Plant Collections Network (PCN) development plan outlines our next phase work with stewartia over the upcoming several years. The results of this work will be shared in future years as we continue to bring these exceptional small flowering trees into commercial production. 2 INTRODUCTION The commitment to building Polly Hill Arboretum’s (PHA) stewartia collection is based on our founder Polly Hill’s history with the genus and our own desire to encourage the cultivation of these superb small-flowering trees in home gardens. -

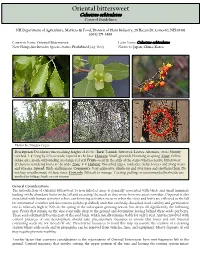

Oriental Bittersweet Orientalcelastrus Bittersweet Orbiculatus Controlcontrol Guidelinesguidelines

Oriental bittersweet OrientalCelastrus bittersweet orbiculatus ControlControl GuidelinesGuidelines NH Department of Agriculture, Markets & Food, Division of Plant Industry, 29 Hazen Dr, Concord, NH 03301 (603) 271-3488 Common Name: Oriental Bittersweet Latin Name: Celastrus orbiculatus New Hampshire Invasive Species Status: Prohibited (Agr 3800) Native to: Japan, China, Korea Photos by: Douglas Cygan Description: Deciduous vine reaching heights of 40-60'. Bark: Tannish, furrowed. Leaves: Alternate, ovate, bluntly toothed, 3-4'' long by 2/3’s as wide, tapered at the base. Flowers: Small, greenish, blooming in spring. Fruit: Yellow dehiscent capsule surrounding an orange-red aril. Fruits occur in the axils of the stems whereas native bittersweet (Celastrus scandens) fruits at the ends. Zone: 4-8. Habitat: Disturbed edges, roadsides, fields, forests and along rivers and streams. Spread: Birds and humans. Comments: Very aggressive, climbs up and over trees and smothers them. Do not buy wreaths made of these vines. Controls: Difficult to manage. Cutting, pulling, or recommended herbicide use applied to foliage, bark, or cut-stump. General Considerations The introduction of Oriental bittersweet to non infested areas is generally associated with birds and small mammals feeding on the abundant fruits in the fall and excreting the seeds as they move from one area to another. Dispersal is also associated with human activities where earth moving activities occur or when the vines and fruits are collected in the fall for ornamental wreathes and decorations (which is prohibited) and then carelessly discarded. Seed viability and germination rate is relatively high at 90% in the spring of the subsequent growing season, but drops off significantly the following year. -

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L. VEGETATIVE KEY TO SPECIES IN CULTIVATION Jan De Langhe (1 October 2014 - 28 May 2015) Vegetative identification key. Introduction: This key is based on vegetative characteristics, and therefore also of use when flowers and fruits are absent. - Use a 10× hand lens to evaluate stipular scars, buds and pubescence in general. - Look at the entire plant. Young specimens, shade, and strong shoots give an atypical view. - Beware of hybridisation, especially with plants raised from seed other than wild origin. Taxa treated in this key: see page 10. Questionable/frequently misapplied names: see page 10. Names referred to synonymy: see page 11. References: - JDL herbarium - living specimens, in various arboreta, botanic gardens and collections - literature: De Meyere, D. - (2001) - Enkele notities omtrent Liriodendron tulipifera, L. chinense en hun hybriden in BDB, p.23-40. Hunt, D. - (1998) - Magnolias and their allies, 304p. Bean, W.J. - (1981) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles VOL.2, p.641-675. - or online edition Clarke, D.L. - (1988) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles supplement, p.318-332. Grimshaw, J. & Bayton, R. - (2009) - Magnolia in New Trees, p.473-506. RHS - (2014) - Magnolia in The Hillier Manual of Trees & Shrubs, p.206-215. Liu, Y.-H., Zeng, Q.-W., Zhou, R.-Z. & Xing, F.-W. - (2004) - Magnolias of China, 391p. Krüssmann, G. - (1977) - Magnolia in Handbuch der Laubgehölze, VOL.3, p.275-288. Meyer, F.G. - (1977) - Magnoliaceae in Flora of North America, VOL.3: online edition Rehder, A. - (1940) - Magnoliaceae in Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs hardy in North America, p.246-253. -

Hydraulic Traits Are More Diverse in Flowers Than in Leaves

Research Hydraulic traits are more diverse in flowers than in leaves Adam B. Roddy1 , Guo-Feng Jiang2,3 , Kunfang Cao2,3 , Kevin A. Simonin4 and Craig R. Brodersen1 1School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA; 2State Key Laboratory of Conservation and Utilization of Subtropical Agrobioresources, Guangxi University, Nanning, Guangxi 530004, China; 3Guangxi Key Laboratory of Forest Ecology and Conservation, College of Forestry, Guangxi University, Nanning, Guangxi 530004, China; 4Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA 94132, USA Summary Author for correspondence: Maintaining water balance has been a critical constraint shaping the evolution of leaf form Adam B. Roddy and function. However, flowers, which are heterotrophic and relatively short-lived, may not Tel: +1 510 224 4432 be constrained by the same physiological and developmental factors. Email: [email protected] We measured physiological parameters derived from pressure–volume curves for leaves Received: 3 December 2018 and flowers of 22 species to characterize the diversity of hydraulic traits in flowers and to Accepted: 11 February 2019 determine whether flowers are governed by the same constraints as leaves. Compared with leaves, flowers had high saturated water content, which was a strong pre- New Phytologist (2019) 223: 193–203 dictor of hydraulic capacitance in both leaves and flowers. Principal component analysis doi: 10.1111/nph.15749 revealed that flowers occupied a different region of multivariate trait space than leaves and that hydraulic traits are more diverse in flowers than in leaves. Key words: diversity, drought tolerance, Without needing to maintain high rates of transpiration, flowers rely on other hydraulic evolution, flower, hydraulics, water relations. -

Towards an Updated Checklist of the Libyan Flora

Towards an updated checklist of the Libyan flora Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 (CC-BY) Open access Gawhari, A. M. H., Jury, S. L. and Culham, A. (2018) Towards an updated checklist of the Libyan flora. Phytotaxa, 338 (1). pp. 1-16. ISSN 1179-3155 doi: https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.1.1 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/76559/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.1.1 Identification Number/DOI: https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.1.1 <https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.1.1> Publisher: Magnolia Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Phytotaxa 338 (1): 001–016 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.338.1.1 Towards an updated checklist of the Libyan flora AHMED M. H. GAWHARI1, 2, STEPHEN L. JURY 2 & ALASTAIR CULHAM 2 1 Botany Department, Cyrenaica Herbarium, Faculty of Sciences, University of Benghazi, Benghazi, Libya E-mail: [email protected] 2 University of Reading Herbarium, The Harborne Building, School of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, Whiteknights, Read- ing, RG6 6AS, U.K. -

Morphology and Morphogenesis of the Seed Cones of the Cupressaceae - Part II Cupressoideae

1 2 Bull. CCP 4 (2): 51-78. (10.2015) A. Jagel & V.M. Dörken Morphology and morphogenesis of the seed cones of the Cupressaceae - part II Cupressoideae Summary The cone morphology of the Cupressoideae genera Calocedrus, Thuja, Thujopsis, Chamaecyparis, Fokienia, Platycladus, Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Cupressus and Juniperus are presented in young stages, at pollination time as well as at maturity. Typical cone diagrams were drawn for each genus. In contrast to the taxodiaceous Cupressaceae, in Cupressoideae outgrowths of the seed-scale do not exist; the seed scale is completely reduced to the ovules, inserted in the axil of the cone scale. The cone scale represents the bract scale and is not a bract- /seed scale complex as is often postulated. Especially within the strongly derived groups of the Cupressoideae an increased number of ovules and the appearance of more than one row of ovules occurs. The ovules in a row develop centripetally. Each row represents one of ascending accessory shoots. Within a cone the ovules develop from proximal to distal. Within the Cupressoideae a distinct tendency can be observed shifting the fertile zone in distal parts of the cone by reducing sterile elements. In some of the most derived taxa the ovules are no longer (only) inserted axillary, but (additionally) terminal at the end of the cone axis or they alternate to the terminal cone scales (Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Juniperus). Such non-axillary ovules could be regarded as derived from axillary ones (Microbiota) or they develop directly from the apical meristem and represent elements of a terminal short-shoot (Tetraclinis, Juniperus). -

Phylogeny and Phylogenetic Taxonomy of Dipsacales, with Special Reference to Sinadoxa and Tetradoxa (Adoxaceae)

PHYLOGENY AND PHYLOGENETIC TAXONOMY OF DIPSACALES, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO SINADOXA AND TETRADOXA (ADOXACEAE) MICHAEL J. DONOGHUE,1 TORSTEN ERIKSSON,2 PATRICK A. REEVES,3 AND RICHARD G. OLMSTEAD 3 Abstract. To further clarify phylogenetic relationships within Dipsacales,we analyzed new and previously pub- lished rbcL sequences, alone and in combination with morphological data. We also examined relationships within Adoxaceae using rbcL and nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences. We conclude from these analyses that Dipsacales comprise two major lineages:Adoxaceae and Caprifoliaceae (sensu Judd et al.,1994), which both contain elements of traditional Caprifoliaceae.Within Adoxaceae, the following relation- ships are strongly supported: (Viburnum (Sambucus (Sinadoxa (Tetradoxa, Adoxa)))). Combined analyses of C ap ri foliaceae yield the fo l l ow i n g : ( C ap ri folieae (Diervilleae (Linnaeeae (Morinaceae (Dipsacaceae (Triplostegia,Valerianaceae)))))). On the basis of these results we provide phylogenetic definitions for the names of several major clades. Within Adoxaceae, Adoxina refers to the clade including Sinadoxa, Tetradoxa, and Adoxa.This lineage is marked by herbaceous habit, reduction in the number of perianth parts,nectaries of mul- ticellular hairs on the perianth,and bifid stamens. The clade including Morinaceae,Valerianaceae, Triplostegia, and Dipsacaceae is here named Valerina. Probable synapomorphies include herbaceousness,presence of an epi- calyx (lost or modified in Valerianaceae), reduced endosperm,and distinctive chemistry, including production of monoterpenoids. The clade containing Valerina plus Linnaeeae we name Linnina. This lineage is distinguished by reduction to four (or fewer) stamens, by abortion of two of the three carpels,and possibly by supernumerary inflorescences bracts. Keywords: Adoxaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Dipsacales, ITS, morphological characters, phylogeny, phylogenetic taxonomy, phylogenetic nomenclature, rbcL, Sinadoxa, Tetradoxa. -

Invasive Plant Inventory 21St Century Planting Design and Management

Tree of Heaven, Ailanthus altissima Species characteristics: • Deciduous Tree • Size: up to 80 feet • Flowers: clusters of yellow-green flowers at the ends of upper branches • Leaves: pinnately compound with 11-14 leaflets • Fruit: seeds develop in the fall, each seed is con tained in a sumara, yellow green changing to orange red in fall, brown in winter • Bark: gray with a snake skin like texture, lenticles WINCHESTER What makes this plant so aggressive? HIGH SCHOOL • Rapid growth rate, saplings can grow 3-4 feet per year • Mature tree can produce 350,00 seeds per year • Seeds are transported by wind and water. • Roots give off a toxin that can inhibit the growth of other plants. • Root sprouts up to 50 feet from trunk. N Why is this plant so damaging to native plant communities? It out competes native species for light. It forms impenetrable SHORE ROAD thickets and tolerates adverse soil conditions. SKILLINGS ROAD 0 50 100 200 Factors that limit species growth: It is intolerant of full shade. Management strategies • Hand pulling of seedlings. • Cutting twice per year, once in June, and again September 15th. • Herbicide application, cut trees and apply undiluted GRIFFIN triclopyr (Brush-B-Gone) to the stump or cut and PHOTOGRAPHY MUSEUM spray resprouts. JENKS CENTER POLICE STATION Species characteristics: • Deciduous woody twining vine FIRE • Size: Can reach 18 meters in height STATION • Flowers: female plants produce small greenish flowers • Leaves: variable in size and shape, alternate arrangement, broadly oblong to sub orbicular,