The Fractionation of Working Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testing Working Memory: an Experimental and Analytical Approach

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2005 Testing Working Memory: An Experimental and Analytical Approach Nicholas Duane Bennett University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Bennett, Nicholas Duane, "Testing Working Memory: An Experimental and Analytical Approach" (2005). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/820 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: TESTING WORKING MEMORY Testing Working Memory: An Experimental and Analytical Approach 2005 Senior Honors Project Nicholas D. Bennett Mentor: Dr. Srinivasan Mahadevan The University of Tennessee Knoxville Abstract The following paper is basically a brief review of my studies in the concentration of cognition under the guidance of Dr. Mahadevan. In addition to demonstrating laboratory procedures, Dr. Mahadevan recommended many of the subsequent references to literature pertaining to various memory constructs. Having acquired a broad taste (but admitted novice skill) for many interpretations, clarifications by and conversations with Dr. Mahadevan have enabled me to document some conclusions here. My hope is to convey some understanding of the history, methods, theories and models I have found to be instrumental to the present-day empirical study of memory. -

Rehabilitation Information Pack a Range of Products from Pearson Assessment for Professionals Working in the Area of Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation Information Pack A range of products from Pearson Assessment for professionals working in the area of rehabilitation The Functional UK Administration and Scoring Manual TFL S Living Scale UK Edition Examiner’s Manual C. Munro Cullum Myron F. Weiner Kathleen C. Saine www.pearsonclinical.co.uk Welcome... Introducing our 2013 Rehabilitation Information Pack Dear Colleague, Pearson (Assessment) is one of the UK’s leading publishers of standardised assessments. Our tests are used by a number of professionals in both health and education settings and we strive to develop and distribute tools that are timely and in line with good practice guidelines. For example, we are mindful of targets set by the Department of Health, for the early recognition of debilitating neurological and cognitive disorders including dementia and the aim for ‘two-thirds of people with dementia [to be] identified and given appropriate support by 2015’. In this pack you will find a range of products that can aid you inidentifying cognitive impairments and assist you in the evaluation of your clients; helping you to plan intervention strategies and enhance your evidence- based practice. Among these assessments is the new Brief Cognitive Status Exam (BCSE) which is designed to assess a client’s cognitive ability quickly and reliably, and the RBANS™ - Update which can be used as a stand-alone “core” battery for the detection and characterization of dementia in the elderly. Together with early diagnosis, assessment of activities of daily living can be vital in assisting service users maintain independence or return to everyday life. The UK-normed Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test- Third Edition, Rookwood Driving Battery and The Functional Living Scales – UK Version all have excellent ecological validity which places assessment in real life context; making the results more meaningful to you as a professional, and your clients. -

Mennyi? Szamok a Termeszetben 2 A

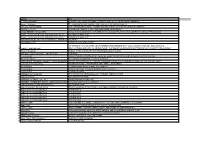

Author Title 1 ? Mennyi? Szamok a termeszetben 2 A. DAVID REDISH. BEYOND THE COGNITIVE MAP : FROM PLACE CELLS TO EPISODIC MEMORY 3 Aaron C.T.Smith Cognitive mechanisms of belief change 4 Aaron L.Berkowitz The improvising mind: cognition and creativity in the musical moment 5 AARON L.BERKOWITZ. THE IMPROVISING MIND : COGNITION AND CREATIVITY IN THE MUSICAL MOMENT 6 AARON T. BECK. COGNITIVE THERAPY AND THE EMOTIONAL DISORDERS 7 Aaron Williamon Musical excellence: strategies and techniques to enhance performance 8 Adger David Language unlimited: the science behind our most creative power 9 AIDAN FEENEY, EVAN HEIT. INDUCTIVE REASONING : EXPERIMENTAL, DEVELOPMENTAL, AND COMPUTATIONAL APPROACHES 10 Alain F. Zuur, Elena N. Ieno, Erik H.W.G.Meesters A beginner`s guide to R 11 Alain F. Zuur, Elena N. Ieno, Erik H.W.G.Meesters A beginner`s guide to R 12 ALAN BADDELEY, Michael W. EYSENCK, AND Michael MEMORYC. ANDERSON. 13 Alan C Love Beyond the meme: development and structure in cultural evolution 14 ALAN GILCHRIST. SEEING BLACK AND WHITE 15 Alan Merriam The anthropology of music RYTHMES ET CHAOS DANS LES SYSTEMES BIOCHIMIQUES ET CELLULAIRES. ENGLISH. BIOCHEMICAL OSCILLATIONS 16 ALBERT GOLDBETER AND CELLULAR RHYTHMS : THE MOLECULAR BASES OF PERIODIC AND CHAOTIC BEHAVIOUR 17 Albert S Bregman Auditory scene analysis: the perceptual organization of sound 18 Albert-Laszlo Barabasi Network Science 19 Alda Mari, Claire Beyssade, Fabio del Prete Genericity 20 Alex Mesoudi Cultural Evolution: how Darwinian theory can explain human culture and synthesize the social sciences 21 Alexander Easton The cognitive neuroscience of social behaviour. 22 ALEXANDER TODOROV Face Value the irresistible influence of first impression 23 ALEXANDER TODOROV, Susan T. -

Working Memory in Perspective

Working Memory in Perspective The Baddeley and Hitch (1974) Working Memory model holds a central place in experimental psychology and continues to be extremely successful in guiding and stimulating research in applied and theoretical domains. Yet the model now faces challenges from conflicting data and competing theories. In this book, experienced researchers in the field address the question: Will the model survive these challenges? They explain why it is so successful, evaluate its weaknesses with respect to opposing data and theories, and present their vision of the future of the model in their particular area of research. The book includes a discussion of the ‘Episodic Buffer’ component which has recently been added to the working memory model. The result is a comprehensive and critical assessment of the working memory model and its contribution to current research in human cognition, cognitive development, neuroscience and computational modelling. This collection serves as a case study to illustrate the range of factors that determine the success or failure of a theory and as a forum for discussing what researchers want from scientific theories. The book begins with an accessible introduction to the model for those new to the field and explains the empirical methods used in working memory research. It concludes by highlighting areas of consensus and suggesting a programme of research to address issues of continuing controversy. Working Memory in Perspective will be a valuable resource to students and researchers alike in the fields of human memory, language, thought and cognitive development. Jackie Andrade is a lecturer in psychology at the University of Sheffield. -

Working Memory and Language: an Overview

Journal of Communication Disorders 36 (2003) 189–208 Working memory and language: an overview Alan Baddeley* Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Bristol, 8 Woodland Rd, Bristol BS8 1TN, UK Received 30 November 2002; received in revised form 25 February 2003; accepted 25 February 2003 Abstract Working memory involves the temporary storage and manipulation of information that is assumed to be necessary for a wide range of complex cognitive activities. In 1974, Baddeley and Hitch proposed that it could be divided into three subsystems, one concerned with verbal and acoustic information, the phonological loop, a second, the visuospatial sketchpad providing its visual equivalent, while both are dependent upon a third atten- tionally-limited control system, the central executive. A fourth subsystem, the episodic buffer, has recently been proposed. These are described in turn, with particular reference to implications for both the normal processing of language, and its potential disorders. Learning outcomes: The reader will be introduced to the concept of a multi-component working memory. Particular emphasis will be placed on the phonological loop component, and (a) its fractionation into a storage and processing component, (b) the neuropsycho- logical evidence for this distinction, and (c) its implication for both native and second language learning. This will be followed by (d) a brief overview of the visuospatial sketchpad and its possible role in language, culminating in (e) discussion of the higher-level control functions of working memory which include (f) the central executive and its multi- dimensional storage system, the episodic buffer. An attempt throughout is made to link the model to its role in both normal and disordered language functions. -

Michel Foucault Ronald C Kessler Graham Colditz Sigmund Freud

ANK RESEARCHER ORGANIZATION H INDEX CITATIONS 1 Michel Foucault Collège de France 296 1026230 2 Ronald C Kessler Harvard University 289 392494 3 Graham Colditz Washington University in St Louis 288 316548 4 Sigmund Freud University of Vienna 284 552109 Brigham and Women's Hospital 5 284 332728 JoAnn E Manson Harvard Medical School 6 Shizuo Akira Osaka University 276 362588 Centre de Sociologie Européenne; 7 274 771039 Pierre Bourdieu Collège de France Massachusetts Institute of Technology 8 273 308874 Robert Langer MIT 9 Eric Lander Broad Institute Harvard MIT 272 454569 10 Bert Vogelstein Johns Hopkins University 270 410260 Brigham and Women's Hospital 11 267 363862 Eugene Braunwald Harvard Medical School Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de 12 264 364838 Michael Graetzel Lausanne 13 Frank B Hu Harvard University 256 307111 14 Yi Hwa Liu Yale University 255 332019 15 M A Caligiuri City of Hope National Medical Center 253 345173 16 Gordon Guyatt McMaster University 252 284725 17 Salim Yusuf McMaster University 250 357419 18 Michael Karin University of California San Diego 250 273000 Yale University; Howard Hughes 19 244 221895 Richard A Flavell Medical Institute 20 T W Robbins University of Cambridge 239 180615 21 Zhong Lin Wang Georgia Institute of Technology 238 234085 22 Martín Heidegger Universität Freiburg 234 335652 23 Paul M Ridker Harvard Medical School 234 318801 24 Daniel Levy National Institutes of Health NIH 232 286694 25 Guido Kroemer INSERM 231 240372 26 Steven A Rosenberg National Institutes of Health NIH 231 224154 Max Planck -

Mechanisms of Social Cognition

PS63CH12-Frith ARI 31 October 2011 11:58 Mechanisms of Social Cognition Chris D. Frith1,3 and Uta Frith2,3 1Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging and 2Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, University College London, WCIN 3AR United Kingdom, and 3Center of Functionally Integrative Neuroscience, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark; email: [email protected], [email protected] Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012. 63:287–313 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on observational learning, imitation, reputation, teaching, mentalizing, August 11, 2011 meta-cognition The Annual Review of Psychology is online at psych.annualreviews.org Abstract This article’s doi: Social animals including humans share a range of social mechanisms that 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100449 are automatic and implicit and enable learning by observation. Learning Copyright c 2012 by Annual Reviews. from others includes imitation of actions and mirroring of emotions. All rights reserved Learning about others, such as their group membership and reputa- by Victoria University of Wellington on 09/28/12. For personal use only. 0066-4308/12/0110-0287$20.00 tion, is crucial for social interactions that depend on trust. For accurate Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012.63:287-313. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org prediction of others’ changeable dispositions, mentalizing is required, i.e., tracking of intentions, desires, and beliefs. Implicit mentalizing is present in infants less than one year old as well as in some nonhuman species. Explicit mentalizing is a meta-cognitive process and enhances the ability to learn about the world through self-monitoring and reflec- tion, and may be uniquely human. -

Visuo-Spatial Working Memory and Individual Differences

VISUO-SPATIAL WORKING MEMORY AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES Essays in Cognitive Psychology UK Editors: Alan Baddeley, University of Bristol, UK Vicki Bruce, University of Stirling, UK North American Editor: Henry L. Roediger, III, Washington University in St. Louis, USA Essays in Cognitive Psychology is designed to meet the need for rapid publication of brief volumes in cognitive psychology. Primary topics will include perception, move- ment and action, attention, memory, mental representation, language, and problem solving. Furthermore, the series seeks to define cognitive psychology in its broadest sense, encompassing all topics either informed by, or informing, the study of mental processes. As such, it covers a wide range of subjects including computational approaches to cognition, cognitive neuroscience, social cognition, and cognitive development, as well as areas more traditionally defined as cognitive psychology. Each volume in the series will make a conceptual contribution to the topic by reviewing and synthesizing the existing research literature, by advancing theory in the area, or by some combination of these missions. The principal aim is that authors will provide an overview of their own highly successful research program in an area. It is also expected that volumes will, to some extent, include an assessment of current know- ledge and identification of possible future trends in research. Each book will be a self- contained unit supplying the advanced reader with a well-structured review of the work described and evaluated. Also available in this series: Mental Models and the Interpretation of Hypothesis-testing Behaviour Anaphora Fenna Poletiek Alan Garnham Superior Memory Memory for Actions John Wilding & Elizabeth Valentine Johannes Engelkamp Anxiety and Cognition Superportraits Michael W. -

Author Title 1 A. DAVID REDISH. BEYOND the COGNITIVE MAP

Author Title 1 A. DAVID REDISH. BEYOND THE COGNITIVE MAP : FROM PLACE CELLS TO EPISODIC MEMORY 2 Aaron L.Berkowitz The improvising mind: cognition and creativity in the musical moment 3 AARON L.BERKOWITZ. THE IMPROVISING MIND : COGNITION AND CREATIVITY IN THE MUSICAL MOMENT 4 AARON T. BECK. COGNITIVE THERAPY AND THE EMOTIONAL DISORDERS 5 AIDAN FEENEY, EVAN HEIT. INDUCTIVE REASONING : EXPERIMENTAL, DEVELOPMENTAL, AND COMPUTATIONAL APPROACHES 6 Alain F. Zuur, Elena N. Ieno, Erik H.W.G.Meesters A beginner`s guide to R 7 Alain F. Zuur, Elena N. Ieno, Erik H.W.G.Meesters A beginner`s guide to R 8 ALAN BADDELEY, Michael W. EYSENCK, AND Michael MEMORYC. ANDERSON. 9 ALAN GILCHRIST. SEEING BLACK AND WHITE RYTHMES ET CHAOS DANS LES SYSTEMES BIOCHIMIQUES ET CELLULAIRES. ENGLISH. BIOCHEMICAL 10 ALBERT GOLDBETER OSCILLATIONS AND CELLULAR RHYTHMS : THE MOLECULAR BASES OF PERIODIC AND CHAOTIC BEHAVIOUR 11 Albert S Bregman Auditory scene analysis: the perceptual organization of sound 12 Alda Mari, Claire Beyssade, Fabio del Prete Genericity 13 Alex Mesoudi Cultural Evolution: how Darwinian theory can explain human culture and synthesize the social sciences 14 Alexander Easton The cognitive neuroscience of social behaviour. 15 ALEXANDER TODOROV, Susan T. FISKE & DEBORAHSOCIAL PRENTICE. NEUROSCIENCE : TOWARD UNDERSTANDING THE UNDERPINNINGS OF THE SOCIAL MIND 16 ALEXANDRA HOROWITZ INSIDE OF A DOG : WHAT DOGS SEE, SMELL, AND KNOW 17 Alfred Blatter Revisiting music theory: a guide to the practice 18 Alison Gopnik Bolcsek a bolcsoben: hogyan gondolkodnak a kisbabak 19 Alison Gopnik A babak filozofiaja 20 ANDREW DUCHOWSKI EYE TRACKING METHODOLOGY : THEORY AND PRACTICE 21 Andrew Gelman Bayesian Data Analysis 22 ANDREW GELMAN .. -

Examining the Role of Working Memory Resources in Following Spoken Instructions

This is a repository copy of Examining the role of working memory resources in following spoken instructions. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/91941/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Yang, T, Allen, RJ and Gathercole, SE (2016) Examining the role of working memory resources in following spoken instructions. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 28 (2). pp. 186-198. ISSN 2044-5911 https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2015.1101118 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 Running head: Working memory in spoken instructions Examining the role of working memory resources in following spoken instructions Tian-xiao Yang, Richard J. Allen and Susan E. Gathercole In press, Journal of Cognitive Psychology Tian-xiao Yang*, 1. -

DOCUMENT RESUME CS 509 793 Research on Spoken Language

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 417 451 CS 509 793 AUTHOR Pisoni, David B. TITLE Research on Spoken Language Processing. Progress Report No. 21 (1996-1997). INSTITUTION Indiana Univ., Bloomington. Dept. of Psychology. SPONS AGENCY National Institutes of Health (DHHS), Bethesda, MD. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 637p. CONTRACT DC-00111; DC-00012 PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) Reports - Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF03/PC26 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Deafness; Error Analysis (Language); Higher Education; *Language Processing; Memory; *Speech Communication; Word Recognition IDENTIFIERS Cochlear Implants; *Indiana University Bloomington; *Speech Perception; Speech Research ABSTRACT This 21st annual progress report summarizes research activities on speech perception and spoken language processing carried out in the Speech Research Laboratory, Department of Psychology, Indiana University in Bloomington. As with previous reports, the goal is to summarize accomplishments during 1996 and 1997 and make them readily available. Some papers in the report are extended manuscripts unau have been prepared &- formal publication, others are short reports of research. The extended manuscripts are: "Speech Perception"(R. Wright and others); "Looking at Lhe 'Stars': A First Report on the Intercorrelations among Measures of Speech Perception, Intelligibility and Language Development in Pediatric Cochlear Implant Users" (D.B. Pisoni and others); "Measures of Phonological Memory Span for Sounds Differing in Discriminability: Some Preliminary Findings" (M. Cleary); "Static vs. Dynamic Faces as Retrieval Cues in Recognition of Spoken Words"(L. Lachs); "Some Observations on Working Memory Tasks and Issues in Cognitive Psychology" (W.D. Goh); "Familiarity, Similarity and Memory for Speech Events" (S.M. Sheffert and R.M. Shiffrin); "Improvements in Speech Perception in Prelingually-Deafened Children: Effects of Device, Communication Mode, and Chronological Age" (T.A. -

Acoustic Epistemologies and Aurality in Sor Juana Inés De La Cruz

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2014 Acoustic Epistemologies and Aurality in Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Sarah E. Finley University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Finley, Sarah E., "Acoustic Epistemologies and Aurality in Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz" (2014). Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies. 16. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/16 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies.