C. P. E. BACH the Solo Keyboard Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Harpsichord: a Research and Information Guide

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository THE HARPSICHORD: A RESEARCH AND INFORMATION GUIDE BY SONIA M. LEE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch, Chair and Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus Donald W. Krummel, Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus John W. Hill Associate Professor Emerita Heidi Von Gunden ABSTRACT This study is an annotated bibliography of selected literature on harpsichord studies published before 2011. It is intended to serve as a guide and as a reference manual for anyone researching the harpsichord or harpsichord related topics, including harpsichord making and maintenance, historical and contemporary harpsichord repertoire, as well as performance practice. This guide is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to provide a user-friendly resource on the subject. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation advisers Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch and Professor Donald W. Krummel for their tremendous help on this project. My gratitude also goes to the other members of my committee, Professor John W. Hill and Professor Heidi Von Gunden, who shared with me their knowledge and wisdom. I am extremely thankful to the librarians and staff of the University of Illinois Library System for assisting me in obtaining obscure and rare publications from numerous libraries and archives throughout the United States and abroad. -

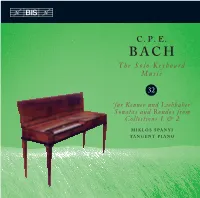

C. P. E. BACH the Solo Keyboard Music

C. P. E. BACH The Solo Keyboard Music 32 ‘für Kenner und Liebhaber’ Sonatas and Rondos from Collections 1 & 2 MIKLÓS SPÁNYI TANGENT PIANO BACH, Carl Philipp Emanuel (1714–88) ‘für Kenner und Liebhaber’ Sonatas from Collection 1, Wq 55 Rondos from Collection 2, Wq 56 Sonata No.1 in C major, Wq 55/1 (H 244) 8'56 1 Prestissimo 3'11 2 Andante 2'31 3 Allegretto 3'10 4 Rondo No.1 in C major, Wq 56/1 (H 260) 8'42 Allegretto Sonata No.4 in A major, Wq 55/4 (H 186) 22'27 5 Allegro assai 9'08 6 Poco adagio 4'46 7 Allegro 8'31 8 Rondo No.2 in D major, Wq 56/3 (H 261) 7'04 Allegretto 2 Sonata No.6 in G major, Wq 55/6 (H 187) 21'07 9 Allegretto moderato 9'57 10 Andante 3'26 11 Allegro di molto 7'41 12 Rondo No.3 in A minor, Wq 56/5 (H 262) 9'14 Poco andante TT: 78'54 Miklós Spányi tangent piano 3 s Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach discussed the publication of his first Hamburg collection of solo keyboard sonatas with Johann Gottlob Immanuel Breitkopf Ain Leipzig (Sechs Clavier-Sonaten für Kenner und Liebhaber), he was al - ready composing works for a projected second collection. To the title of this collec - tion Bach added nebst einigen Rondos fürs Forte-Piano (‘together with some rondos for the fortepiano’). The fortepiano offered new possibilities to composers and key - board players, and Bach’s title emphasized its suitability for the three rondos of the collection. -

A Aurora Do (Forte)Piano

PERSONE, P. A aurora do (forte)piano. Per Musi, Belo Horizonte, n.20, 2009, p.22-33. A aurora do (forte)piano Pedro Persone (UNESP/ FAPESP, São Paulo) [email protected]; http://fortepiano.org Resumo. Este artigo revisita a aurora do fortepiano, instrumento que se tornaria ponto de convergência no fazer musical de fins do século XVIII até meados do XX, e apresenta referências documentais sobre o início da invenção da mecânica de Bartolomeo Cristofori, bem como documentações de outros projetos não Cristoforianos. Palavras-chave: Piano, Fortepiano, Cristofori, Tangentflügel, Piano tangente. The dawn of the (forte)piano Abstract. This article reviews the dawn of the fortepiano, an instrument central to music making from the second half of Eighteenth century to the middle of the Twentieth century. It presents documents that describe the beginning of Cristofori’s invention as well as non-Cristofori documents on the same subject. Keywords: Piano, Fortepiano, Cristofori, Tangentflügel, Tangent piano. 1- Os princípios de um novo instrumento Antes do advento do registro de patentes, muitas vezes mais antigo instrumento conhecido, um “octave virginal” poderia ser difícil conectar a invenção ao seu criador - a ou espineta construído em 1587 por Franciscus Bonafinis, idéia da patente é mais comum ao século XIX. Com a criação teve sua mecânica original substituída por uma mecânica da lei de patentes, por volta de 1790 nos Estados Unidos, a martelos tangentes em 1632. toda nova invenção, mudança, ou aprimoramento podiam ser diretamente relacionados a seu inventor ou executor. Jean Marius (?-1720), um hábil matemático, com No caso particular do piano, podemos traçar suas origens graduação em leis, inventor do clavecin-brisé (cravo e desenvolvimentos, sendo possível determinar a provável dobrável), submeteu em 1716 à Académie Royale des data, o lugar e seu inventor. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Three keyboard concertos by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Bach’s original keyboard concertos. The sources transmit- are included in the present volume: the Concerto in B-flat ting the three works similarly reflect their differing histo- Major, Wq 28 (H 434); the Concerto in A Major, Wq 29 ries; whereas we have the composer’s autograph score and (H 437); and the Concerto in B Minor, Wq 30 (H 440). house parts for Wq 30, no such authoritative documenta- All three works are listed in the catalogue of Bach’s estate tion survives for either Wq 28 or 29. (NV 1790, pp. 31–32) in the section devoted to the con- certos: Concertos in B-flat Major and A Major, No. 29. B. dur. B[erlin]. 1751. Clavier, 2 Violinen, Bratsche und Wq 28 and 29 Baß; ist auch für das Violoncell und die Flöte gesezt. No. 30. A. dur. P[otsdam]. 1753. Clavier, 2 Violinen, Bratsche Wq 28 and 29 are the second and third of three concertos und Baß; ist auch für das Violoncell und die Flöte gesezt. that, in the words of NV 1790, were “also set for violon- 1 No. 31. H. moll. P. 1753. Clavier, 2 Violinen, Bratsche und Baß. cello and flute.” Along with Wq 26, these were the first documented instances in which Bach wrote multiple ver- While Wq 28–30 are numbered successively in NV 1790, sions of a concerto for different solo instruments (see table these works differ in their histories in ways that have left 1), a practice that remained exceptional for him.2 We do a mark on the nature of the pieces themselves. -

Mozartiana Rarities and Arrangements Performed on Historical Keyboards

includes WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDINGS MOZARTIANA RARITIES AND ARRANGEMENTS PERFORMED ON HISTORICAL KEYBOARDS WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART © HNH International MICHAEL TSALKA MICHAEL TSALKA WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Pianist and Early Keyboard performer Michael Tsalka has won numerous prizes in Europe, the United States, the MOZARTIANA Middle East, Asia and Latin America. A versatile musician, RARITIES AND ARRANGEMENTS PERFORMED he performs repertoire from the early Baroque to the ON HISTORICAL KEYBOARDS present day with equal virtuosity. He obtained a Bachelor’s degree from Tel Aviv University and continued his studies in Germany and Italy. From 2002 to 2008 he studied at MICHAEL TSALKA, Temple University under the guidance of Joyce Lindorff, Tangentenflügel 1–$, ¡–•, pantalon square piano %–) Lambert Orkis and Harvey Wedeen. Tsalka holds three degrees from that institution: Master’s degrees in both chamber music and harpsichord performance, and a Catalogue Number: GP849 Doctorate in piano performance. Other mentors include Recording Dates: 2–3 October 2018 Dario di Rosa, Malcolm Bilson, David Shemer, Charles Recording Venue: Rochuskapelle in Wangen im Allgäu, Germany Rosen and Sandra Mangsen. Michael Tsalka maintains a Producers: Pooya Radbon, Michael Tsalka © Olga Masri de Mussali busy concert schedule with recent performance highlights Engineer: Andreas Koslik including Zhonghe Hall in the Forbidden City, Beijing, Editors: Michael Tsalka and Andreas Koslik Palacio de Bellas Artes Theatre in Mexico City, The Royal Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, Pianos: Berner Tangentenflügel and Maucher Pantalon Square Piano from the Pooya Radbon Collection Piano Technician: Pooya Radbon the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, The Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Booklet Notes: Michael Tsalka, Pooya Radbon Mozarteum in Salzburg, Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Elbphilharmonie in German Translation: Cris Posslac Hamburg and Sydney Conservatorium of Music. -

Issue No. 8 Published by 'The British Harpsichord Society' EDITORIAL & INTRODUCTION a Word from Our Guest Editor- NA

Issue No. 8 Published by ‘The British Harpsichord Society’ JANUARY 2014 ______________________________________________________________________________ EDITORIAL & INTRODUCTION 1 A word from our Guest Editor- NAOMI OKUDA NEWS 4 Awards to harpsichordists, Masaki Suzuki & Zuzana Růžičková; Christophe Rousset plays at Edinburgh; The latest News from the Horniman Museum – the winners, an exhibition & a conference; 60 years of Diplomatic Relations celebrated with a harpsichord recital; A 1789 Kirckman in a NT film; A new Junior Fellowship in Harpsichord/Continuo; The JMRO call for Papers & the HKSNA Conference-‘Four Centuries of Masterpieces’ and call for Proposals REPORT 7 The BHS Competition Finals Concert, July 27th PAMELA NASH FEATURES Musical Instruments in a Hostile climate AKIO OBUCHI 11 Eastern Promise- Touring with Melvyn Tan SIMON NEAL 14 The experiences of a Harpsichord player in Japan MITZI MEYERSON 17 Looking for a Harpsichord from afar MASUMI YAMAMOTO 19 Vermeer and Music; SHIGEYUKI KOIDE 20 ….Realised dream of a music iconographer Miracle in the Far East MOXAM KAYANO 22 Harpsichords in the City of Music, and in Part 2 ANDREW WOODERSON 23 ..…a closer look at the 1646 Italian Harpsichord 27 Making new Jacks using a 3-D printer MALCOLM MESSITER 34 YOUR LETTERS Continuing the Harpsichord v Piano debate 38 And finally …….ON A LIGHTER NOTE 42 Please keep sending your contributions to [email protected] Please note that opinions voiced here are those of the individual authors and not necessarily those of the BHS. All material remains the copyright of the individual authors and may not be reproduced without their express permission. EDITORIAL A Happy New Year to you all I hope you will enjoy this Issue that gives us a glimpse into the Early Music scene on the other side of the world. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven (3 Vol

BEETHOVEN Complete Fortepiano Concertos Arthur Schoonderwoerd & Cristofori 1 Sommaire CD1 Texte de Denis Grenier FR ENG Texte d’Arthur Schoonderwoerd FR ENG CD2 Texte de Denis Grenier FR ENG Texte d’Arthur Schoonderwoerd FR ENG CD3 Texte de Denis Grenier FR ENG Texte d’Arthur Schoonderwoerd FR ENG 2 ARTHUR SCHOONDERWOERD Les francs-comtois le connaissent bien, après 8 éditions du Festival de Musiques Anciennes de Besançon/Montfaucon et les nombreux concerts, pleins de charme, qu’il y a donnés. Ogre pour les enfants, aux côtés d’Alexandra Rübner, pianiste « récitant » de merveilleuses mélodies françaises avec Isabelle Druet, pianiste concertant avec Cristofori dans les chefs-d’œuvre de Beethoven et de Mozart, Arthur Schoonderwoerd offre de fabuleux moments de convivialité et de découverte autour de tous ses pianos, clavicordes, pianoforte, tous différents… Arthur Schoonderwoerd et ses pianos habitent le petit village de Montfaucon, il est considéré comme l’un des pianofortistes les plus importants de sa génération. Son terrain de prédilection va des recherches sur l’interprétation de la musique pour piano des 18ème et 19ème siècles et sur le répertoire à tort oublié de cette période, à l’observation de la grande diversité d’instruments à clavier qui jalonnèrent ces deux siècles. Après avoir obtenu, entre autres, un diplôme de concertiste en piano moderne au conservatoire d’Utrecht (Pays-Bas), il fait des études de piano historique au Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris dans la classe de Jos van Immerseel. En 1995, il obtient un Premier Prix à l’unanimité dans cette discipline et termine ensuite ses études par un brillant cycle de perfectionnement. -

The Harpsichord: a Research and Information Guide

THE HARPSICHORD: A RESEARCH AND INFORMATION GUIDE BY SONIA M. LEE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch, Chair and Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus Donald W. Krummel, Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus John W. Hill Associate Professor Emerita Heidi Von Gunden ABSTRACT This study is an annotated bibliography of selected literature on harpsichord studies published before 2011. It is intended to serve as a guide and as a reference manual for anyone researching the harpsichord or harpsichord related topics, including harpsichord making and maintenance, historical and contemporary harpsichord repertoire, as well as performance practice. This guide is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to provide a user-friendly resource on the subject. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation advisers Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch and Professor Donald W. Krummel for their tremendous help on this project. My gratitude also goes to the other members of my committee, Professor John W. Hill and Professor Heidi Von Gunden, who shared with me their knowledge and wisdom. I am extremely thankful to the librarians and staff of the University of Illinois Library System for assisting me in obtaining obscure and rare publications from numerous libraries and archives throughout the United States and abroad. Among the many friends who provided support and encouragement are Clara, Carmen, Cibele and Marcelo, Hilda, Iker, James and Diana, Kydalla, Lynn, Maria-Carmen, Réjean, Vivian, and Yolo. -

M. Steinert Collection Keyed and Stringed

E E C OLLECTI ON M . ST I N RT K E Y E D A N D S T R I N G E D I N T M E N S RU TS . W ITH V ARIOU S TREATI S ES ON THE HI STO R Y OF THES E I N STR U M ENTS THE M ETH OD OF PLA Y IN G THE M A N D , , T I I F LU C ON M I AL A T HE R N EN E U S C R . M O R R I S S T E I E RT N , N EW V HA CO . EN . NN I L L U S T R A T E D . P I : PAP C LOT R C E ER , H , F . T R ET BA R C . 1 89 3 , by . firms of R O T A . S , 1 F RA N K F O RT S TRE E T N O . 4 , 4m. em DED I C A T E D T O MY F R I E N D ‘ F K . A . H J I I S S . A P N , O F O D O G A D L N N , EN L N , A S A MA R K O F A PPRE I A T I C O N . PR E F A C E . T HE articles i n this p a mphlet have bee n written for a tw ofold o he of . I n o de to c ta t t purpose First. -

The Industrial Revolution and Music

1 The Industrial Revolution and Music Jeremy Montagu Originally a series of lectures given in the early 1990s in the Faculty of Music, University of Oxford © Jeremy Montagu 2018 The author’s moral rights have been asserted Hataf Segol Publications 2018 Typeset in XƎLATEX by Simon Montagu Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 The Organ 15 3 The Piano 29 4 Exotica 43 5 String Instruments 59 6 The Flute 75 7 Single Reeds 91 8 Double Reeds 105 9 Trumpets and Horns 119 10 Valved Cornets and Bugles 135 11 Percussion 147 12 Bands, Choirs, and Factories 163 iii 1 Introduction In this first session, I want to set the scene for this series of lectures and to produce a general background against which we can discuss the effect of the Industrial Revolution on our instruments, on the way in which, and the reasons why, music was performed, the genesis of our modern orchestra and its instruments, and all the conditions under which music has been performed for, roughly, the last two or three centuries. I am using the term ‘Industrial Revolution’ in its widest sense – not necessarily from the first use of industrial machinery at Coalbrookdale, for example (the Industrial Revolution did start in England), or whatever other landmark of the beginnings of our modern age that a variety of people have used. What I have in mind is the change from a mainly rural, mainly feudal economy to an urban, partly industrial, economy, with two important, for us, concomitant changes: a rise in the level of tech- nology and the rise of an urban middle class. -

Anmeldelser Af Pianist Michael Tsalka

Anmeldelser af pianist Michael Tsalka: Review of Naxos (Grand Piano) recording of Tuerk's Keyboard Sonatas 1-12 Grand Piano GP 627- 28 (2CD's) David Denton, David's Review Corner, Classical Music Review, Sep. 4, 2012 "If we had not become so besotted by everything composed by Johann Sebastian Bach, we might have spared a thought for Daniel Gottlob Turk. Born in 1750, the year of Bach’s death, he had a solid education in the German style of composition, placing him at some distance from the outgoing flamboyance of the Italian keyboard style we have come to know from the works of Domenico Scarlatti. Turk’s music has the expert craftsmanship that takes no liberties nor does it take musical styles forwards, his ability to create instantly memorable melodic material not particularly evident from this disc, though at the same time it is easily and readily enjoyable. That the discs are inventive comes from Michael Tsalka’s use of five historical keyboards, for, as the excellent notes with the disc explain, Turk lived at a time when there was in use more diversity of keyboard instruments than in any other musical period. So with the clavichord, spinet, harpsichord, fortepiano and tangent piano, we hear how music of the period can change depending on the instrument used...Try track 1, disc 1- the opening of the C major - played on the spinet, then move to track 4 - the opening of the B flat major - and the music springs to life with the added piquancy in the harpsichord.sound. Then to the robust but more muffled sound of the fortepiano in the following D major sonata.