Issue No. 8 Published by 'The British Harpsichord Society' EDITORIAL & INTRODUCTION a Word from Our Guest Editor- NA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UMD NEWS SERVICE 724-8801, Ext 210 September 2, 1966 DULUTH

Release on receipt UMD NEWS SERVICE 724-8801, Ext 210 September 2, 1966 DULUTH -- As a student and teacher of baroque music (1700s), music styles and history, UMD Associate Professor C. Lindsley Edson inherited a per- former's desire for accuracy and precision and an "interest in (musical) in- struments of the time." The keyboard instrument of the baroque period was the harpischord. In his quest for authenticity, Edson took a sabbatical leave in England dur- ing 1964-65. While there he decided to purchase a harpsichord. When the instrument arrived on the ocean-going vessel Manchester Shipper in July via the St. Lawrence Seaway, the Edsons were settled in their new home at 3500 London Road and a special music room was ready. The harpsichord was made by Robert Goble & Son, Limited (Oxford, England) and, in contrast to the piano, the strings are plucked and not struck. It has a larger range than the piano and Edson's model has two keyboards. "You can create more dependable subtleties, combinations and tonal qualities on a harpsichord than are possible on a piano because the mechani- cal plucking of the strings is more accurate than the human touch," said Edson. He explained that the force with which each key of the harpsichord is struck does not matter, since each one of the plectrum (plucking devices) creates the same note strength as any other. There are five sets of plectrum and they engage the strings through the use of six pedals. "The pedals give you several interesting combinations," he said. "Actually, I have four harpsichords in one." Edson's music room is soundproof and has independent temperature control to protect the instrument. -

GOLDBERG VARIATIONS - English Suite No

BHP 901 - BACH: GOLDBERG VARIATIONS - English Suite No. 5 in e - Millicent Silver, Harpsichord _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ This disc, the first in our Heritage Performances Series, celebrates the career and the artistry of Millicent Silver, who for some forty years was well-known as a regular performer in London and on BBC Radio both as soloist and as harpsichordist with the London Harpsichord Ensemble which she founded with her husband John Francis. Though she made very few recordings, we are delighted to preserve this recording of the Goldberg Variations for its musical integrity, its warmth, and particularly the use of tonal dynamics (adding or subtracting of 4’ and 16’ stops to the basic 8’) which enhances the dramatic architecture. Millicent Irene Silver was born in South London on 17 November 1905. Her father, Alfred Silver, had been a boy chorister at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor where his singing attracted the attention of Queen Victoria, who had him give special performances for her. He earned his living playing the violin and oboe. His wife Amelia was an accomplished and busy piano teacher. Millicent was the second of their four children, and her musical talent became evident in time-honoured fashion when she was discovered at the age of three picking out on the family’s piano the tunes she had heard her elder brother practising. Eventually Millicent Silver won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London where, as was more common in those days, she studied equally both piano and violin. She was awarded the Chappell Silver Medal for piano playing and, in 1928, the College’s Tagore Gold Medal for the best student of her year. -

The Harpsichord: a Research and Information Guide

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository THE HARPSICHORD: A RESEARCH AND INFORMATION GUIDE BY SONIA M. LEE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch, Chair and Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus Donald W. Krummel, Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus John W. Hill Associate Professor Emerita Heidi Von Gunden ABSTRACT This study is an annotated bibliography of selected literature on harpsichord studies published before 2011. It is intended to serve as a guide and as a reference manual for anyone researching the harpsichord or harpsichord related topics, including harpsichord making and maintenance, historical and contemporary harpsichord repertoire, as well as performance practice. This guide is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to provide a user-friendly resource on the subject. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation advisers Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch and Professor Donald W. Krummel for their tremendous help on this project. My gratitude also goes to the other members of my committee, Professor John W. Hill and Professor Heidi Von Gunden, who shared with me their knowledge and wisdom. I am extremely thankful to the librarians and staff of the University of Illinois Library System for assisting me in obtaining obscure and rare publications from numerous libraries and archives throughout the United States and abroad. -

'The British Harpsichord Society' April 2021

ISSUE No. 16 Published by ‘The British Harpsichord Society’ April 2021 ________________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION 1 A word from our Guest Editor - Dr CHRISTOPHER D. LEWIS 2 FEATURES • Recording at Home during Covid 19 REBECCA PECHEFSKY 4 • Celebrating Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach COREY JAMASON 8 • Summer School, Dartington 2021 JANE CHAPMAN 14 • A Review; Zoji PAMELA NASH 19 • Early Keyboard Duets FRANCIS KNIGHTS 21 • Musings on being a Harpsichordist without Gigs JONATHAN SALZEDO 34 • Me and my Harpsichord; a Romance in Three Acts ANDREW WATSON 39 • The Art of Illusion ANDREW WILSON-DICKSON 46 • Real-time Continuo Collaboration BRADLEY LEHMAN 51 • 1960s a la 1760s PAUL AYRES 55 • Project ‘Issoudun 1648-2023’ CLAVECIN EN FRANCE 60 IN MEMORIAM • John Donald Henry (1945 – 2020) NICHOLAS LANE with 63 friends and colleagues ANNOUNCEMENTS 88 • Competitions, Conferences & Courses Please keep sending your contributions to [email protected] Please note that opinions voiced here are those of the individual authors and not necessarily those of the BHS. All material remains the copyright of the individual authors and may not be reproduced without their express permission. INTRODUCTION ••• Welcome to Sounding Board No.16 ••• Our thanks to Dr Christopher Lewis for agreeing to be our Guest Editor for this edition, especially at such a difficult time when the demands of University teaching became even more complex and time consuming. Indeed, it has been a challenging year for all musicians but ever resourceful, they have found creative ways to overcome the problems imposed by the Covid restrictions. Our thanks too to all our contributors who share with us such fascinating accounts of their musical activities during lock-down. -

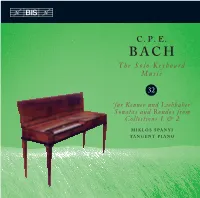

C. P. E. BACH the Solo Keyboard Music

C. P. E. BACH The Solo Keyboard Music 32 ‘für Kenner und Liebhaber’ Sonatas and Rondos from Collections 1 & 2 MIKLÓS SPÁNYI TANGENT PIANO BACH, Carl Philipp Emanuel (1714–88) ‘für Kenner und Liebhaber’ Sonatas from Collection 1, Wq 55 Rondos from Collection 2, Wq 56 Sonata No.1 in C major, Wq 55/1 (H 244) 8'56 1 Prestissimo 3'11 2 Andante 2'31 3 Allegretto 3'10 4 Rondo No.1 in C major, Wq 56/1 (H 260) 8'42 Allegretto Sonata No.4 in A major, Wq 55/4 (H 186) 22'27 5 Allegro assai 9'08 6 Poco adagio 4'46 7 Allegro 8'31 8 Rondo No.2 in D major, Wq 56/3 (H 261) 7'04 Allegretto 2 Sonata No.6 in G major, Wq 55/6 (H 187) 21'07 9 Allegretto moderato 9'57 10 Andante 3'26 11 Allegro di molto 7'41 12 Rondo No.3 in A minor, Wq 56/5 (H 262) 9'14 Poco andante TT: 78'54 Miklós Spányi tangent piano 3 s Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach discussed the publication of his first Hamburg collection of solo keyboard sonatas with Johann Gottlob Immanuel Breitkopf Ain Leipzig (Sechs Clavier-Sonaten für Kenner und Liebhaber), he was al - ready composing works for a projected second collection. To the title of this collec - tion Bach added nebst einigen Rondos fürs Forte-Piano (‘together with some rondos for the fortepiano’). The fortepiano offered new possibilities to composers and key - board players, and Bach’s title emphasized its suitability for the three rondos of the collection. -

A Aurora Do (Forte)Piano

PERSONE, P. A aurora do (forte)piano. Per Musi, Belo Horizonte, n.20, 2009, p.22-33. A aurora do (forte)piano Pedro Persone (UNESP/ FAPESP, São Paulo) [email protected]; http://fortepiano.org Resumo. Este artigo revisita a aurora do fortepiano, instrumento que se tornaria ponto de convergência no fazer musical de fins do século XVIII até meados do XX, e apresenta referências documentais sobre o início da invenção da mecânica de Bartolomeo Cristofori, bem como documentações de outros projetos não Cristoforianos. Palavras-chave: Piano, Fortepiano, Cristofori, Tangentflügel, Piano tangente. The dawn of the (forte)piano Abstract. This article reviews the dawn of the fortepiano, an instrument central to music making from the second half of Eighteenth century to the middle of the Twentieth century. It presents documents that describe the beginning of Cristofori’s invention as well as non-Cristofori documents on the same subject. Keywords: Piano, Fortepiano, Cristofori, Tangentflügel, Tangent piano. 1- Os princípios de um novo instrumento Antes do advento do registro de patentes, muitas vezes mais antigo instrumento conhecido, um “octave virginal” poderia ser difícil conectar a invenção ao seu criador - a ou espineta construído em 1587 por Franciscus Bonafinis, idéia da patente é mais comum ao século XIX. Com a criação teve sua mecânica original substituída por uma mecânica da lei de patentes, por volta de 1790 nos Estados Unidos, a martelos tangentes em 1632. toda nova invenção, mudança, ou aprimoramento podiam ser diretamente relacionados a seu inventor ou executor. Jean Marius (?-1720), um hábil matemático, com No caso particular do piano, podemos traçar suas origens graduação em leis, inventor do clavecin-brisé (cravo e desenvolvimentos, sendo possível determinar a provável dobrável), submeteu em 1716 à Académie Royale des data, o lugar e seu inventor. -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Arnold Dolmetsch and the Clavichord 10/12/07 21:14

Arnold Dolmetsch and the Clavichord 10/12/07 21:14 The British Clavichord Society at Haslemere: the work of Arnold Dolmetsch Kenneth Mobbs From British Clavichord Society Newsletter No. 4, February 1996 ‘Plus fait Douceur que Violence’ (Gentleness achieves more than Violence) is the motto to be found on Arnold Dolmetsch’s personally signed instruments. The phrase could equally be applied to his son Carl’s gracious hosting of the British Clavichord Society at Haslemere on September 2nd, 1995 and the moving musical illustrations played by Ruth Dyson Dr Carl Dolmetsch, a very active 84-year-old, gave a most interesting and informative lecture on the work of his father, with special reference to his advocacy of the clavichord. Speaking from a prepared script, nevertheless he could not resist interspersing anecdotes and asides into the talk, and these all helped to give a vivid picture of life with such a multifaceted father, with whom he shared the first 29 years of his life (‘It seemed much longer – that is meant in the best sense’). He sketched how the tradition of clavichord playing just spanned the 19th century before being rekindled with such practical enthusiasm and energy. Arnold’s grandfather (Friedrich, b. 1782) founded a music school in Zurich, and his aunts had remembered as children practising along with fellow-pupils on clavichords in different corners of the same room, without hearing one another. Dr Carl described his feelings of joy and astonishment when, in 1947, he found that he had been staying by chance in the old school, by then converted into a hotel. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Three keyboard concertos by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Bach’s original keyboard concertos. The sources transmit- are included in the present volume: the Concerto in B-flat ting the three works similarly reflect their differing histo- Major, Wq 28 (H 434); the Concerto in A Major, Wq 29 ries; whereas we have the composer’s autograph score and (H 437); and the Concerto in B Minor, Wq 30 (H 440). house parts for Wq 30, no such authoritative documenta- All three works are listed in the catalogue of Bach’s estate tion survives for either Wq 28 or 29. (NV 1790, pp. 31–32) in the section devoted to the con- certos: Concertos in B-flat Major and A Major, No. 29. B. dur. B[erlin]. 1751. Clavier, 2 Violinen, Bratsche und Wq 28 and 29 Baß; ist auch für das Violoncell und die Flöte gesezt. No. 30. A. dur. P[otsdam]. 1753. Clavier, 2 Violinen, Bratsche Wq 28 and 29 are the second and third of three concertos und Baß; ist auch für das Violoncell und die Flöte gesezt. that, in the words of NV 1790, were “also set for violon- 1 No. 31. H. moll. P. 1753. Clavier, 2 Violinen, Bratsche und Baß. cello and flute.” Along with Wq 26, these were the first documented instances in which Bach wrote multiple ver- While Wq 28–30 are numbered successively in NV 1790, sions of a concerto for different solo instruments (see table these works differ in their histories in ways that have left 1), a practice that remained exceptional for him.2 We do a mark on the nature of the pieces themselves. -

Mozartiana Rarities and Arrangements Performed on Historical Keyboards

includes WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDINGS MOZARTIANA RARITIES AND ARRANGEMENTS PERFORMED ON HISTORICAL KEYBOARDS WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART © HNH International MICHAEL TSALKA MICHAEL TSALKA WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Pianist and Early Keyboard performer Michael Tsalka has won numerous prizes in Europe, the United States, the MOZARTIANA Middle East, Asia and Latin America. A versatile musician, RARITIES AND ARRANGEMENTS PERFORMED he performs repertoire from the early Baroque to the ON HISTORICAL KEYBOARDS present day with equal virtuosity. He obtained a Bachelor’s degree from Tel Aviv University and continued his studies in Germany and Italy. From 2002 to 2008 he studied at MICHAEL TSALKA, Temple University under the guidance of Joyce Lindorff, Tangentenflügel 1–$, ¡–•, pantalon square piano %–) Lambert Orkis and Harvey Wedeen. Tsalka holds three degrees from that institution: Master’s degrees in both chamber music and harpsichord performance, and a Catalogue Number: GP849 Doctorate in piano performance. Other mentors include Recording Dates: 2–3 October 2018 Dario di Rosa, Malcolm Bilson, David Shemer, Charles Recording Venue: Rochuskapelle in Wangen im Allgäu, Germany Rosen and Sandra Mangsen. Michael Tsalka maintains a Producers: Pooya Radbon, Michael Tsalka © Olga Masri de Mussali busy concert schedule with recent performance highlights Engineer: Andreas Koslik including Zhonghe Hall in the Forbidden City, Beijing, Editors: Michael Tsalka and Andreas Koslik Palacio de Bellas Artes Theatre in Mexico City, The Royal Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, Pianos: Berner Tangentenflügel and Maucher Pantalon Square Piano from the Pooya Radbon Collection Piano Technician: Pooya Radbon the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, The Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Booklet Notes: Michael Tsalka, Pooya Radbon Mozarteum in Salzburg, Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Elbphilharmonie in German Translation: Cris Posslac Hamburg and Sydney Conservatorium of Music. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven (3 Vol

BEETHOVEN Complete Fortepiano Concertos Arthur Schoonderwoerd & Cristofori 1 Sommaire CD1 Texte de Denis Grenier FR ENG Texte d’Arthur Schoonderwoerd FR ENG CD2 Texte de Denis Grenier FR ENG Texte d’Arthur Schoonderwoerd FR ENG CD3 Texte de Denis Grenier FR ENG Texte d’Arthur Schoonderwoerd FR ENG 2 ARTHUR SCHOONDERWOERD Les francs-comtois le connaissent bien, après 8 éditions du Festival de Musiques Anciennes de Besançon/Montfaucon et les nombreux concerts, pleins de charme, qu’il y a donnés. Ogre pour les enfants, aux côtés d’Alexandra Rübner, pianiste « récitant » de merveilleuses mélodies françaises avec Isabelle Druet, pianiste concertant avec Cristofori dans les chefs-d’œuvre de Beethoven et de Mozart, Arthur Schoonderwoerd offre de fabuleux moments de convivialité et de découverte autour de tous ses pianos, clavicordes, pianoforte, tous différents… Arthur Schoonderwoerd et ses pianos habitent le petit village de Montfaucon, il est considéré comme l’un des pianofortistes les plus importants de sa génération. Son terrain de prédilection va des recherches sur l’interprétation de la musique pour piano des 18ème et 19ème siècles et sur le répertoire à tort oublié de cette période, à l’observation de la grande diversité d’instruments à clavier qui jalonnèrent ces deux siècles. Après avoir obtenu, entre autres, un diplôme de concertiste en piano moderne au conservatoire d’Utrecht (Pays-Bas), il fait des études de piano historique au Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris dans la classe de Jos van Immerseel. En 1995, il obtient un Premier Prix à l’unanimité dans cette discipline et termine ensuite ses études par un brillant cycle de perfectionnement. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Department of Music Volume 1 of 1 The Harpsichord in Twentieth-Century Britain by Christopher David Lewis Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Music Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy THE HARPSICHORD IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY BRITAIN by CHRISTOPHER DAVID LEWIS This dissertation provides an overview of the history of the harpsichord in twentieth- century Britain. It takes as its starting point the history of the revival harpsichord in the early part of the century, how the instrument affected both performance of historic music and the composition of modern music and the factors that contributed to its decline.