Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

Thursday Playlist

February 20, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “Lesser artists borrow, great artists steal.” — Igor Stravinsky Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6 in D Budapest Festival Orchestra/Fischer Philips 456 570 028945657028 Awake! Symphony in D, "The Petrification of Phineus and 00:13 Buy Now! Dittersdorf Cantilena/Shepherd Chandos 8564/5 5014682856423 his Friends" 00:31 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. 076 in E flat Academy of Ancient Music/Hogwood BBC MM253 n/a Vonsattel/Sussmann/Swensen/O'Neill 01:01 Buy Now! Franck Piano Quintet in F minor Music@Menlo Live n/a 653738268220 /Finckel New York Chamber Music 01:35 Buy Now! Lully Suite ~ The Forced Marriage Dorian 90189 053479018922 Ensemble/Pederson 01:45 Buy Now! Mozart Fantasia in C minor, K. 475 Lars Vogt EMI 36080 094633608023 02:00 Buy Now! Weber Overture ~ Der Freischutz Philharmonia/Klemperer EMI 13073 n/a 02:11 Buy Now! Strauss, R. 2nd mvt (Andante) ~ Cello Sonata in F, Op. 6 Coppey/le Sage Harmonia Mundi 911550 794881314324 02:20 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 56 "Scottish" London Classical Players/Norrington EMI 54000 077775400021 Rimsky- 02:59 Buy Now! Ivan the Terrible National Philharmonic/Stokowski Sony Classical 62647 074646264720 Korsakov 03:04 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky The Seasons (orchestrated version) Moscow Chamber Orchestra/Orbelian Delos 3255 013491325521 03:48 Buy Now! Handel Concerto Grosso in G, Op. 6 No. 1 Guildhall String Ensemble/Salter RCA 7895 078635789522 04:01 Buy Now! Devienne Flute Concerto No. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

N Ew Y O R K F Lu T E F a Ir 2021

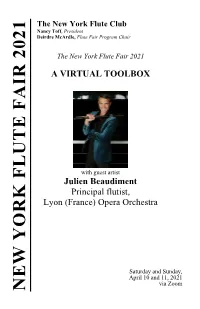

The New York Flute Club Nancy Toff, President Deirdre McArdle, Flute Fair Program Chair The New York Flute Fair 2021 A VIRTUAL TOOLBOX with guest artist Julien Beaudiment Principal flutist, Lyon (France) Opera Orchestra Saturday and Sunday, April 10 and 11, 2021 via Zoom NEW YORK FLUTE FAIR 2021 BOARD OF DIRECTORS NANCY TOFF, President PATRICIA ZUBER, First Vice President KAORU HINATA, Second Vice President DEIRDRE MCARDLE, Recording Secretary KATHERINE SAENGER, Membership Secretary MAY YU WU, Treasurer AMY APPLETON JEFF MITCHELL JENNY CLINE NICOLE SCHROEDER RAIMATO DIANE COUZENS LINDA RAPPAPORT FRED MARCUSA JAYN ROSENFELD JUDITH MENDENHALL RIE SCHMIDT MALCOLM SPECTOR ADVISORY BOARD JEANNE BAXTRESSER ROBERT LANGEVIN STEFÁN RAGNAR HÖSKULDSSON MICHAEL PARLOFF SUE ANN KAHN RENÉE SIEBERT PAST PRESIDENTS Georges Barrère, 1920-1944 Eleanor Lawrence, 1979-1982 John Wummer, 1944-1947 John Solum, 1983-1986 Milton Wittgenstein, 1947-1952 Eleanor Lawrence, 1986-1989 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1952-1955 Sue Ann Kahn, 1989-1992 Frederick Wilkins, 1955-1957 Nancy Toff, 1992-1995 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1957-1960 Rie Schmidt, 1995-1998 Paige Brook, 1960-1963 Patricia Spencer, 1998-2001 Mildred Hunt Wummer, 1963-1964 Jan Vinci, 2001-2002 Maurice S. Rosen, 1964-1967 Jayn Rosenfeld, 2002-2005 Harry H. Moskovitz, 1967-1970 David Wechsler, 2005-2008 Paige Brook, 1970-1973 Nancy Toff, 2008-2011 Eleanor Lawrence, 1973-1976 John McMurtery, 2011-2012 Harold Jones, 1976-1979 Wendy Stern, 2012-2015 Patricia Zuber, 2015-2018 FLUTE FAIR STAFF Program Chair: Deirdre McArdle -

Download Booklet

95782 The cello concerto genre has a relatively short history. Before the 19th century, the only composers a few other works, including Monn’s fine, characterful Cello Concerto in G minor. Monn died of of stature who wrote such works were Vivaldi, C.P.E. Bach, Haydn and Boccherini. Considering the tuberculosis at the age of 33. problem inherent in the cello’s lower register, the potential difficulty of projecting its tone against Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) made phenomenal contributions to the history of the symphony, the weight of an orchestra, it is rather ironic that most of the great concertos for the instrument the string quartet, the piano sonata and the piano trio. He generally found concerto form less were composed later than the Baroque or Classical periods. The orchestra of these earlier periods stimulating to his creative imagination, but he did compose several fine examples. In 1961 the was smaller and lighter – a more accommodating accompaniment for the cello – whereas during unearthing of a set of parts for Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C major in Radenín Castle (now in the 19th century the symphony orchestra was significantly expanded, so that composers had to the Czech Republic) proved to be one of the most exciting discoveries in 20th-century musicology. take more care to avoid overwhelming the soloist. Probably dating from the early 1760s, the concerto is believed to have been composed for Joseph Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) composed several hundred concertos while employed as a violin Weigl, principal cellist of Haydn’s orchestra. This is the more rhythmically arresting of Haydn’s teacher (and, from 1716, as ‘maestro dei concerti’) at the Venetian girls’ orphanage known as authentic cello concertos. -

PICCOLO/FLUTE AUDITION REPERTOIRE LIST Preliminary and Semifinal Rounds: October 27 - 29, 2014 Final Round: November 24, 2014 Onstage, Jones Hall

PICCOLO/FLUTE AUDITION REPERTOIRE LIST Preliminary and Semifinal Rounds: October 27 - 29, 2014 Final Round: November 24, 2014 Onstage, Jones Hall Solo Pieces: Piccolo: Liebermann Concerto, Mvt. I m. 145 – m. 208 Taffanel Andante Pastoral et Scherzettino* m. 1- m.28 Flute: Mozart Flute Concerto in G major Mvt II: m. 10 – m.27 Bizet Entr’acte (w/piano accompaniment m.1 – m. 23 from Theodore Presser Orchestral Excerpts) Semi-Final Round may begin with piano accompaniment for solo pieces listed above. There will be no opportunity to rehearse with a pianist beforehand. Candidates may tune before reading through each selection. One restart per piece is allowed if needed. Houston Symphony tunes to A=442. Piccolo Excerpts Bartok Concerto for Orchestra Mvt. III: m. 29 – m. 33; m. 123 – end Bartok Concerto for Orchestra Mvt. V: m. 418 – m.429 Beethoven Symphony No. 9 Mvt. IV: m. 343- m.432 or 16 before H to K Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique Mvt. V: 7 after #63 – 5 before #65 Brahms Haydn Variations Variation VIII (complete) Mahler Symphony No. 2 Mvt. V ‘Der Grosse Appell’: 5 after #30 - #31 Ravel Daphnis and Chloe 3 after #156 – 2 after #159 Ravel Mother Goose Mvt. II: #7 – #8 Ravel Mother Goose Mvt. III: beginning – 5 after #3; #7 – #8 Ravel Piano Concerto in G Major Beginning to #1 Rossini La Gazza Ladra m.1- m. 11; 18 after D - 25 after D; 32 after G - 39 after G Shostakovich Symphony No. 8 Mvt. II: m. 65 – m.113 Shostakovich Symphony No. 8 Mvt. IV: m. -

Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 ANTONÍN DVORÁK

I believe Prokofiev is the most imaginative orchestrator of all time. He uses the percussion and the special effects of the strings in new and different ways; always tasteful, never too much of any one thing. His Symphony No. 5 is one of the best illustrations of all of that. JANET HALL, NCS VIOLIN Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 ANTONÍN DVORÁK BORN September 8, 1841, near Prague; died May 1, 1904, in Prague PREMIERE Composed 1894-1895; first performance March 19, 1896, in London, conducted by the composer with Leo Stern as soloist OVERVIEW During the three years that Dvořák was teaching at the National Conservatory of Music in New York City, he was subject to the same emotions as most other travelers away from home for a long time: invigoration and homesickness. America served to stir his creative energies, and during his stay, from 1892 to 1895, he composed some of his greatest scores: the “New World” Symphony, the Op. 96 Quartet (“American”), and the Cello Concerto. He was keenly aware of the new musical experiences to be discovered in the land far from his beloved Bohemia when he wrote, “The musician must prick up his ears for music. When he walks he should listen to every whistling boy, every street singer or organ grinder. I myself am often so fascinated by these people that I can scarcely tear myself away.” But he missed his home and, while he was composing the Cello Concerto, looked eagerly forward to returning. He opened his heart in a letter to a friend in Prague: “Now I am finishing the finale of the Cello Concerto. -

An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru

Flute Repertoire from Japan: An Analysis of Twentieth-Century Flute Sonatas by Ikuma Dan, Hikaru Hayashi, and Akira Tamba D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Daniel Ryan Gallagher, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Caroline Hartig Professor Karen Pierson 1 Copyrighted by Daniel Ryan Gallagher 2019 2 Abstract Despite the significant number of compositions by influential Japanese composers, Japanese flute repertoire remains largely unknown outside of Japan. Apart from standard unaccompanied works by Tōru Takemitsu and Kazuo Fukushima, other Japanese flute compositions have yet to establish a permanent place in the standard flute repertoire. The purpose of this document is to broaden awareness of Japanese flute compositions through the discussion, analysis, and evaluation of substantial flute sonatas by three important Japanese composers: Ikuma Dan (1924-2001), Hikaru Hayashi (1931- 2012), and Akira Tamba (b. 1932). A brief history of traditional Japanese flute music, a summary of Western influences in Japan’s musical development, and an overview of major Japanese flute compositions are included to provide historical and musical context for the composers and works in this document. Discussions on each composer’s background, flute works, and compositional style inform the following flute sonata analyses, which reveal the unique musical language and characteristics that qualify each work for inclusion in the standard flute repertoire. These analyses intend to increase awareness and performance of other Japanese flute compositions specifically and lesser- known repertoire generally. -

A Pedagogical Analysis of Dvorak's Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op

A Pedagogical Analysis of Dvorak’s Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 by Zhuojun Bian B.A., The Tianjin Normal University, 2006 M.Mus., University of Victoria, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Cello) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2017 © Zhuojun Bian, 2017 Abstract I first heard Antonin Dvorak’s Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 when I was 13 years old. It was a memorable experience for me, and I was struck by the melodies, the power, and the emotion in the work. As I became more familiar with the piece I came to understand that it holds a significant position in the cello repertory. It has been praised extensively by cellists, conductors, composers, and audiences, and is one of the most frequently performed cello concertos since it was premiered by the English cellist Leo Stern in London on March 19th, 1896, with Dvorak himself conducting the Philharmonic Society Orchestra. In this document I provide a pedagogical method as a practical guide for students and cello teachers who are planning on learning this concerto. Using a variety of historical sources, I provide a comprehensive understanding of some of the technical challenges presented by this work and I propose creative and effective methods for conquering these challenges. Most current studies of Dvorak’s concerto are devoted to the analysis of its structure, melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, instrumentation, and orchestration. Unlike those studies, this thesis investigates etudes and student concertos that were both precursors to – and contemporary with – Dvorak’s concerto. -

Rep List 1.Pub

Richmond Symphony Orchestra League Student Concerto Competition Repertoire Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Guitar & percussion students are welcome to participate; Please contact Anne Hoffler, contest coordinator, at aahoffl[email protected] for repertoire approval no later than November 30. VIOLIN Faure Elegy, Op. 24 Bach All Violin concerti Haydn Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major Beethoven Violin Concerto in D major Haydn Cello Concerto No. 2 in D major Beethoven Romance No. 1 in G major Kabalevsky Cello Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 49 Beethoven Romance No. 2 in F major Lalo Cello Concerto in D minor Bériot Scéne de Ballet, Op. 100 Rubinstein Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op.96 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 7 in G major Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op.33 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 9 in A minor Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 119 Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor Schumann Cello Concerto in A minor Haydn All Violin concerti Shostakovich Concerto for Cello No. 1 Kabalevsky Violin Concerto in C Major, Op. 48 Stamitz All Cello concerti Lalo Symphonie Espagnole R. Strauss Romanze in F major Massenet Méditation from Thaïs Tchaikovsky Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op.33 Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 Vivaldi All Cello concerti Mozart Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat major Mozart Violin Concerto No. 2 in D major BASS Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major Bottesini Double Bass Concerto No.2 in B minor Mozart Violin Concerto No. -

Connections Between Bach and Cassadó D Minor Suites

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-1-2021 CONNECTIONS BETWEEN BACH AND CASSADÓ D MINOR SUITES Eunice Koh [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Koh, Eunice. "CONNECTIONS BETWEEN BACH AND CASSADÓ D MINOR SUITES." (Spring 2021). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONNECTIONS BETWEEN BACH AND CASSADÓ D MINOR CELLO SUITES by Eunice Koh Kai’En B.Mus., Nayang Academy of Fine Arts – Royal College of Music, 2017 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Master of Music School of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2021 Copyright by Eunice Koh Kai’En, 2021 All Rights Reserved RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL CONNECTIONS BETWEEN BACH AND CASSADÓ D MINOR CELLO SUITES by Eunice Koh Kai’En A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Music Approved by: Dr. Eric Lenz, Chair Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 01, 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The journey to achieve my Masters in Music Performance would not have been possible without my teacher, Dr. Eric Lenz. I am truly appreciative of his unwavering support and dedication for my pursuit for excellence. My growth in cello performance and pedagogy will definitely be aspects that will carry through my later years as a cello performer and educator.