Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 ANTONÍN DVORÁK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOSVC Weblist 8: Erato Box 51

DOSVC Weblist 8: Erato Box 51 Label Serial No Composer, Work or Title Artists Record Condition notes Erato EPR 15554 Honegger Symphonie, Roussel Suite Munch, L'ORTF, Lamoreux Near Mint cutout notch UR Erato NUM 75106 Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique Conlon, Orch Nat de France Near Mint Gatefold album Erato NUM 75126 Schumann: Cello Concerto/Four Horns Lodeon/Devoyon/Guschlbauer Factory Sealed Cut Out notch Erato NUM 75146 Mahler/Strauss: Quartets for strings & piano Quatuor Ivaldi Near Mint Cut Out notch Erato NUM 75166 Corelli: Christmas Concerto Scimone, Solisti Veneti Factory Sealed Gatefold album Erato NUM 75167 Mozart: Sonata in D Major/C Minor/Fantasy Pires Factory Sealed Erato NUM 75168 Chopin Sonata 2 and 3 Duchable Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch Erato NUM 75169 Handel: Alcina Gardiner, English Baroque Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch 2 copies Erato NUM 75170 Offenbach/Cherubini/Saint-Saens/Godard Horne/Foster Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch Erato NUM 75171 vocal by: Tosti/Rotoli/Brogi/Denza Raimondi/Scimone Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch Erato NUM 75174 Delalande: Simphonies pour les Soupers du Roy Paillard Chamb Orch Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch Erato NUM 75177 Liszt: Sonata in B Minor/Two Legends Duchable Factory Sealed Erato NUM 75178 Schumann: Scenes from Childhood/Forest Pires Factory Sealed Gatefold album, CO notch Erato NUM 75180 Mozart: Symphonies 38 & 39 Conlon , Scottish Chamber Near Mint Cut Out notch Erato NUM 75181 Motets of Vivaldi Scimone, Solisti Veneti Near Mint Cut Out -

Elgar, Cello Concerto in E Minor

Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85 i. Adagio; Moderato ii. Lento; Allegro molto iii. Adagio iv. Allegro; Moderato; Allegro, ma non troppo; Poco più lento; Adagio Edward Elgar enjoys a curious reputation in his own country. To many, he is the composer of overtly nationalistic music such as Pomp and Circumstance, the musical incarnation of Edwardian imperialism. Although early works such as the Enigma Variations and Imperial March garnered him praise and fame, it is his later works from 1918-1919 that are much more autobiographical in content – none more so than the Cello Concerto in E minor. The Concerto was mostly composed between 1918 and 1919 at Brinkwells, a cottage in the Sussex woods where he wrote three other chamber works – the Violin Sonata, String Quartet and Piano Quintet. Like these other Brinkwells compositions, the Cello Concerto is a deeply introspective work which reveals much about the composer’s state of mind: an aging artist concerned about his waning popularity, his wife’s failing health, and reflecting on the horrors of the First World War. Despite a grossly under-rehearsed première at the Queen’s Hall on 27 October 1919, it has since been established as perhaps the finest cello concerto in the repertoire, alongside Dvořák’s, and the only work of Elgar’s to enjoy regular performances outside the English-speaking world. The Cello Concerto is an emotionally draining work not only for the players but also the listener, its overwhelming mood one of melancholy and autumnal world-weariness. The first movement opens with a declamatory, grandiose statement by the soloist leading, in almost improvisatory style, into a lilting melody; there is a wistfully lyrical middle section before the opening melody returns. -

Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello

Saturday Evening, January 25, 2020, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello SAMUEL BARBER (1910–81) Toccata Festiva (1960) DANIEL FICARRI, Organ DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–75) Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 (1966) Largo Allegretto Allegretto DANIEL HASS, Cello Intermission CHRISTOPHER ROUSE (1949–2019) Processional (2014) JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–97) Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 (1877) Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso Allegro con spirito Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes, including an intermission This performance is made possible with support from the Celia Ascher Fund for Juilliard. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Juilliard About the Program the organ’s and the orchestra’s full ranges. A fluid approach to rhythm and meter By Jay Goodwin provides momentum and bite, and intricate passagework—including a dazzling cadenza Toccata Festiva for the pedals that sets the organist’s feet SAMUEL BARBER to dancing—calls to mind the great organ Born: March 9, 1910, in West Chester, music of the Baroque era. Pennsylvania Died: January 23, 1981, in New York City Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH In terms of scale, pipe organs are Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg different from every other type of Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow musical instrument, and designing and assembling a new one can be a challenge There are several reasons that of architecture and engineering as complex Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. -

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

11 7 Thseason

2016- 17 (117TH SEASON) Repertoire Bach Cantata No. 150, “Nach Dir, Herr, verlanget Feb. 23-25, 2017 mich”* Violin Concerto No. 1 Mar. 15-16, 2017 Bartók Bluebeard’s Castle Mar. 2-4, 2017 Bates Alternative Energy* Apr. 6-9, 2017 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 4 Feb. 2-4, 2017 Selections from The Creatures of Prometheus Apr. 6-9, 2017 Symphony No. 2 Dec. 8-10, 2016 Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”) Mar. 10-12, 2017 Symphony No. 6 (“Pastoral”) Nov. 25-27, 2016 Violin Concerto Nov. 3-5, 2016 Berg Violin Concerto Mar. 10-12, 2017 Berlioz Le Corsaire Overture Oct. 7-8, 2016 Harold in Italy Jan. 26-27, 2017 Symphonie fantastique Sep. 22-24, 2016; Oct. 7-8, 2016 Bernstein Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs Mar. 30-Apr. 1, 2017 Symphony No. 1 (“Jeremiah”) May 3-6, 2017 Brahms Symphony No. 1 Oct. 27-29, 2016 Symphony No. 2 Nov. 3-5, 2016 Symphony No. 3 Feb. 17-19, 2017 Symphony No. 4 Feb. 23-25, 2017 Brahms/transcr. Selections from Eleven Choral Preludes Feb. 23-25, 2017 Glanert (world premiere of transcriptions) Britten War Requiem Mar. 23-25, 2017 Canteloube Selections from Songs of the Auvergne Jan. 12-14, 2017 Chabrier Joyeuse Marche** Jan. 12-14, 2017 – more – January 2016—All programs and artists subject to change. PAGE 2 The Philadelphia Orchestra 2016-17 Season Repertoire Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 Jan. 19-24, 2017 Piano Concerto No. 2 Sep. 22-24, 2016 Dutilleux Métaboles Oct. 27-29, 2016 Dvořák Symphony No. 8 Mar. 15-16, 2017 Symphony No. -

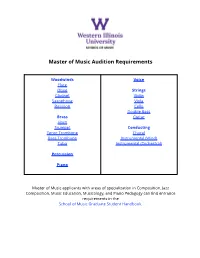

Audition Requirements

Master of Music Audition Requirements Woodwinds Voice Flute Oboe Strings Clarinet Violin Saxophone Viola Bassoon Cello Double Bass Brass Guitar Horn Trumpet Conducting Tenor Trombone Choral Bass Trombone Instrumental (Wind) Tuba Instrumental (Orchestral) Percussion Piano Master of Music applicants with areas of specialization in Composition, Jazz Composition, Music Education, Musicology, and Piano Pedagogy can find entrance requirements in the School of Music Graduate Student Handbook. Flute Faculty: Dr. Suyeon Ko; Email: [email protected] • Mozart: Concerto in G Major or D Major, K. 313 or K. 314 (Movements I and II) • A 19th- or 20th-century French work from Flute Music by French Composers or equivalent • An unaccompanied 20th- or 21st-century work • Five orchestral excerpts from Baxtresser, Orchestral Excerpts for Flute, or equivalent • Sight reading Oboe Faculty: Emily Hart; Email: [email protected] • Choose two from the following: ◦ Saint-Saëns or Poulenc sonata (Movement I) ◦ Mozart or Haydn concerto (Movement III) ◦ Any Telemann or Vivaldi concerto or sonata (Movements I and II) ◦ Britten Six Metamorphoses (any three movements) • Choose two of the following orchestral excerpts (all excerpts may be found in the Rothwell books, Difficult Passages, published by Boosey and Hawkes): ◦ Brahms: Violin Concerto (slow movement excerpt) ◦ Rossini: La Scala di Seta (slow and fast excerpts) ◦ Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) ◦ Prokofiev: Symphony No. 1 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) • Sight reading Clarinet Faculty: Eric Ginsberg; Email: [email protected] • Choose two movements from one of the following: ◦ Mozart: Concerto in A Major, K. 622 ◦ Weber: Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. -

Cellist Zuill Bailey with Helen Kim and the KSU Symphony Orchestra

SCHOOL of MUSIC where PASSION is Zuill Bailey,heard Cello featuring Helen Kim, Violin Robert Henry, Piano KSU Symphony Orchestra Nathaniel F. Parker, Music Director and Conductor Wednesday, October 9, 2019 | 8:00 PM Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall musicKSU.com 1 heard Program LUKAS FOSS (1922-2009) CAPRICCIO MAX BRUCH (1838-1920) KOL NIDREI, OPUS 47 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893) VARIATIONS ON A ROCOCO THEME, OPUS 33 Zuill Bailey, Cello Robert Henry, Piano –INTERMISSION– JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) CONCERTO FOR VIOLIN, CELLO, AND ORCHESTRA IN A MINOR, OPUS 102 I. ALLEGRO II. ANDANTE III. VIVACE NON TROPPO Zuill Bailey, Cello Helen Kim, Violin Kennesaw State University Symphony Orchestra Nathaniel F. Parker, Conductor We welcome all guests with special needs and offer the following services: easy access, companion seating locations, accessible restrooms, and assisted listening devices. Please contact a patron services representative at 470-578-6650 to request services. 2 Kennesaw State University School of Music KSU Symphony Orchestra Personnel Nathaniel F. Parker, Music Director & Conductor Personnel listed alphabetically to emphasize the importance of each part. Rotational seating is used in all woodwind, brass, and percussion sections. Flute Violin Cello Don Cofrancesco Melissa Ake^, Garrett Clay Lorin Green concertmaster Laci Divine Jayna Burton Colin Gregoire^, principal Oboe Abigail Carpenter Jair Griffin Emily Gunby Robert Cox^ Joseph Grunkmeyer, Robert Simon Mary Catherine Davis associate principal -

Franz Anton Hoffmeister’S Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra in D Major a Scholarly Performance Edition

FRANZ ANTON HOFFMEISTER’S CONCERTO FOR VIOLONCELLO AND ORCHESTRA IN D MAJOR A SCHOLARLY PERFORMANCE EDITION by Sonja Kraus Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2019 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Emilio Colón, Research Director and Chair ______________________________________ Kristina Muxfeldt ______________________________________ Peter Stumpf ______________________________________ Mimi Zweig September 3, 2019 ii Copyright © 2019 Sonja Kraus iii Acknowledgements Completing this work would not have been possible without the continuous and dedicated support of many people. First and foremost, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to my teacher and mentor Prof. Emilio Colón for his relentless support and his knowledgeable advice throughout my doctoral degree and the creation of this edition of the Hoffmeister Cello Concerto. The way he lives his life as a compassionate human being and dedicated musician inspired me to search for a topic that I am truly passionate about and led me to a life filled with purpose. I thank my other committee members Prof. Mimi Zweig and Prof. Peter Stumpf for their time and commitment throughout my studies. I could not have wished for a more positive and encouraging committee. I also thank Dr. Kristina Muxfeldt for being my music history advisor with an open ear for my questions and helpful comments throughout my time at Indiana University. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

UCLA Symphony Programs 2005-2019

UCLA SYMPHONY 2005 - 2019 November 30, 2005 Haydn Symphony No. 88 Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 102 Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 2, Op. 17 (Little Russian) Neal Stulberg, conductor and pianist Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * March 6, 2006 Stravinsky Suite No. 2 for Small Orchestra Mozart Clarinet Concerto, K. 622 Beethoven Symphony No. 1, Op. 21 Denexxel Domingo, clarinet Masters and doctoral students of Donald Neuen, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * June 9, 2006 Fauré Suite from Pélléas et Mélisande Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations, Op. 33 Rimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade, Op. 35 Isaac Melamed, cello John Carter and Daniel Cummings, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * November 29, 2006 Bernstein Overture to Candide Haydn Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Cello, Oboe and Bassoon, Op. 84 Puccini Preludio Sinfonico Liszt Les Préludes (Symphonic Poem No. 3) Mary Hofman, violin Isaac Melamed, cello Michelle An, oboe Amy Gillick, bassoon Daniel Cummings, Georgios Kountouris, Neal Stulberg, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * March 14, 2007 DANCE PARTY! Dvorak Slavonic Dance No. 7 in C major, Op. 72 Saint-Saens Danse Macabre, Op. 40 Falla Ritual Fire Dance from El Amor Brujo Piazzolla Tangazo Tchaikowsky Three Dances from Swan Lake Debussy Danse Sacrée et Danse Profane for harp and strings Glière Russian Sailors' Dance from The Red Poppy Copland Hoedown from Rodeo Sousa Hands Across the Sea Lindsay Strand-Polyak, violin Jacque Marshall, harp Masters and doctoral students of Donald Neuen, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA * * * * * May 30, 2007 Mozart Symphony No. 35 (Haffner), K. 385 Ney Rosauro Concerto for Marimba and String Orchestra Moussorgsky/Ravel Pictures from an Exhibition Jamie Strowbridge, marimba Daniel Cummings and Georgios Kountouris, conductors Schoenberg Hall; UCLA December 5, 2007 Mozart Overture to Don Giovanni Rheinberger Concerto for Organ No.