A Study of Vocal Influences in Robert Schumann's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

[email protected] N

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED May 28, 2015 February 17, 2015 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC TO RETURN TO BRAVO! VAIL FOR 13th-ANNUAL SUMMER RESIDENCY, JULY 24–31, 2015 Music Director Alan Gilbert To Lead Three Programs Bramwell Tovey and Joshua Weilerstein Also To Conduct Soloists To Include Violinist Midori, Cellist Alisa Weilerstein, Pianists Jon Kimura Parker and Anne-Marie McDermott, Acting Concertmaster Sheryl Staples, Principal Viola Cynthia Phelps, Soprano Julia Bullock, and Tenor Ben Bliss New York Philharmonic Musicians To Perform Chamber Concert The New York Philharmonic will return to Bravo! Vail in Colorado for the Orchestra’s 13th- annual summer residency there, featuring six concerts July 24–31, 2015, as well as a chamber music concert performed by Philharmonic musicians. Music Director Alan Gilbert will conduct three programs, July 29–31, including an all-American program and works by Mendelssohn, Mahler, Mozart, and Shostakovich. The other Philharmonic concerts, conducted by Bramwell Tovey (July 24 and 26) and former New York Philharmonic Assistant Conductor Joshua Weilerstein (July 25), will feature works by Grieg, Elgar, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, and Richard Strauss, among others. The soloists appearing during the Orchestra’s residency are pianists Jon Kimura Parker and Anne-Marie McDermott, cellist Alisa Weilerstein, violinist Midori, soprano Julia Bullock and tenor Ben Bliss, and Acting Concertmaster Sheryl Staples and Principal Viola Cynthia Phelps. The New York Philharmonic has performed at Bravo! Vail each summer since 2003. Alan Gilbert will lead the concert on Wednesday, July 29, featuring Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, with Midori as soloist, and Mahler’s Symphony No. -

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) The Concertizing Clarinet in the Music of the 20th- 21st Centuries Yu Zhao Department of Musical Upbringing and Education Institute of Music, Theatre and Choreography Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia Saint-Petersburg, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—The article deals with stating the problem of a clarinet concert of the 20-21 centuries (one should note in research in ontology of the genre of Clarinet Concert in 20-21 this regard S. E. Artemyev‟s full-featured thesis considering centuries. The author identifies genre variants of long forms the Concerto for clarinet and orchestra of the 18th century). for solo clarinet with orchestra or instrumental ensemble and proposes further steps in making such a research, as well. II. A SHORT GUIDE IN THE HISTORY OF THE CLARINET Keywords—instrumental concert; concertizing; concerto; CONCERT GENRE concert genres; genre diversity Studies in the executive mastership are connected with a research of the evolution of the genres of instrumental music. I. INTRODUCTION The initial period of genesis and development of clarinet concert is investigated widely. Contemporary music in its various genres has become in many aspects a subject of scrupulous studies in musicology. It is known that the most early is the composition of Our research deals with professional problematics of the Antonio Paganelli indicated by the author as Concerto per instrumental concert genre, viewed more narrowly, namely, Clareto (1733). Possibly, it was written for chalumeau, the connected with clarinet performance. instrument-predecessor of the clarinet itself. But, before this time clarinet was used as one of the concertizing instruments The purpose of this article is to identify the situation in the genre of Concerto Grosso, particularly by J. -

Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello

Saturday Evening, January 25, 2020, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Marin Alsop, Conductor Daniel Ficarri, Organ Daniel Hass, Cello SAMUEL BARBER (1910–81) Toccata Festiva (1960) DANIEL FICARRI, Organ DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–75) Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 (1966) Largo Allegretto Allegretto DANIEL HASS, Cello Intermission CHRISTOPHER ROUSE (1949–2019) Processional (2014) JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833–97) Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 (1877) Allegro non troppo Adagio non troppo Allegretto grazioso Allegro con spirito Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 50 minutes, including an intermission This performance is made possible with support from the Celia Ascher Fund for Juilliard. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Juilliard About the Program the organ’s and the orchestra’s full ranges. A fluid approach to rhythm and meter By Jay Goodwin provides momentum and bite, and intricate passagework—including a dazzling cadenza Toccata Festiva for the pedals that sets the organist’s feet SAMUEL BARBER to dancing—calls to mind the great organ Born: March 9, 1910, in West Chester, music of the Baroque era. Pennsylvania Died: January 23, 1981, in New York City Cello Concerto No. 2 in G major, Op. 126 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH In terms of scale, pipe organs are Born: September 25, 1906, in Saint Petersburg different from every other type of Died: August 9, 1975, in Moscow musical instrument, and designing and assembling a new one can be a challenge There are several reasons that of architecture and engineering as complex Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

Heralding a New Enlightenment

Peculiarities of Clarinet Concertos Form-Building in the Second Half of the 20th Century and the Beginning of the 21st Century Marina Chernaya and Yu Zhao* Abstract: The article deals with clarinet concertos composed in the 20th– 21st centuries. Many different works have been created, either in one or few parts; the longest concert that is mentioned has seven parts (by K. Meyer, 2000). Most of the concertos have 3 parts and the fast-slowly-fast kind of structure connected with the Italian overture; sometimes, the scheme has variants. Our question is: How does the concerto genre function during this period? To answer, we had to search many musical compositions. Sometimes the clarinet is accompanied by orchestra, other times it is surrounded by an ensemble of instruments. More than 100 concertos were found and analyzed. Examples of such concertos were written by C. Nielsen, P. Boulez, J. Adams, C. Debussy, M. Arnold, A. Copland, P. Hindemith, I. Stravinsky, S. Vassilenko, and the attention in the article is focused on them. A special complete analysis is made as regards “Domaines” for clarinet and 21 instruments divided in 6 groups, by Pierre Boulez that had a great role for the concert routine, based on the “aleatoric” principle. The conclusions underline the significant development of the clarinet concerto genre in the 20th -21st centuries, the high diversity of the compositions’ structures, the considerable expressiveness and technicality together with the soloist’s part in the expressive concertizing (as a rule). Further studies suggest the analysis of stylistic and structural peculiarities of the found compositions that are apparently to win their popularity with performers and listeners. -

2020-21 Season Brochure

2020 SEA- This year. This season. This orchestra. This music director. Our This performance. This artist. World This moment. This breath. This breath. 2021 SON This breath. Don’t blink. ThePhiladelphiaOrchestra MUSIC DIRECTOR YANNICK NÉZET-SÉGUIN our world Ours is a world divided. And yet, night after night, live music brings audiences together, gifting them with a shared experience. This season, Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin and The Philadelphia Orchestra invite you to experience the transformative power of fellowship through a bold exploration of sound. 2 2020–21 Season 3 “For me, music is more than an art form. It’s an artistic force connecting us to each other and to the world around us. I love that our concerts create a space for people to gather as a community—to explore and experience an incredible spectrum of music. Sometimes, we spend an evening in the concert hall together, and it’s simply some hours of joy and beauty. Other times there may be an additional purpose, music in dialogue with an issue or an idea, maybe historic or current, or even a thought that is still not fully formed in our minds and hearts. What’s wonderful is that music gives voice to ideas and feelings that words alone do not; it touches all aspects of our being. Music inspires us to reflect deeply, and music brings us great joy, and so much more. In the end, music connects us more deeply to Our World NOW.” —Yannick Nézet-Séguin 4 2020–21 Season 5 philorch.org / 215.893.1955 6A Thursday Yannick Leads Return to Brahms and Ravel Favorites the Academy Garrick Ohlsson Thursday, October 1 / 7:30 PM Thursday, January 21 / 7:30 PM Thursday, March 25 / 7:30 PM Academy of Music, Philadelphia Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor Lisa Batiashvili Violin Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Garrick Ohlsson Piano Hai-Ye Ni Cello Westminster Symphonic Choir Ravel Le Tombeau de Couperin Joe Miller Director Szymanowski Violin Concerto No. -

11 7 Thseason

2016- 17 (117TH SEASON) Repertoire Bach Cantata No. 150, “Nach Dir, Herr, verlanget Feb. 23-25, 2017 mich”* Violin Concerto No. 1 Mar. 15-16, 2017 Bartók Bluebeard’s Castle Mar. 2-4, 2017 Bates Alternative Energy* Apr. 6-9, 2017 Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 4 Feb. 2-4, 2017 Selections from The Creatures of Prometheus Apr. 6-9, 2017 Symphony No. 2 Dec. 8-10, 2016 Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”) Mar. 10-12, 2017 Symphony No. 6 (“Pastoral”) Nov. 25-27, 2016 Violin Concerto Nov. 3-5, 2016 Berg Violin Concerto Mar. 10-12, 2017 Berlioz Le Corsaire Overture Oct. 7-8, 2016 Harold in Italy Jan. 26-27, 2017 Symphonie fantastique Sep. 22-24, 2016; Oct. 7-8, 2016 Bernstein Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs Mar. 30-Apr. 1, 2017 Symphony No. 1 (“Jeremiah”) May 3-6, 2017 Brahms Symphony No. 1 Oct. 27-29, 2016 Symphony No. 2 Nov. 3-5, 2016 Symphony No. 3 Feb. 17-19, 2017 Symphony No. 4 Feb. 23-25, 2017 Brahms/transcr. Selections from Eleven Choral Preludes Feb. 23-25, 2017 Glanert (world premiere of transcriptions) Britten War Requiem Mar. 23-25, 2017 Canteloube Selections from Songs of the Auvergne Jan. 12-14, 2017 Chabrier Joyeuse Marche** Jan. 12-14, 2017 – more – January 2016—All programs and artists subject to change. PAGE 2 The Philadelphia Orchestra 2016-17 Season Repertoire Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 Jan. 19-24, 2017 Piano Concerto No. 2 Sep. 22-24, 2016 Dutilleux Métaboles Oct. 27-29, 2016 Dvořák Symphony No. 8 Mar. 15-16, 2017 Symphony No. -

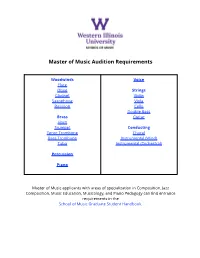

Audition Requirements

Master of Music Audition Requirements Woodwinds Voice Flute Oboe Strings Clarinet Violin Saxophone Viola Bassoon Cello Double Bass Brass Guitar Horn Trumpet Conducting Tenor Trombone Choral Bass Trombone Instrumental (Wind) Tuba Instrumental (Orchestral) Percussion Piano Master of Music applicants with areas of specialization in Composition, Jazz Composition, Music Education, Musicology, and Piano Pedagogy can find entrance requirements in the School of Music Graduate Student Handbook. Flute Faculty: Dr. Suyeon Ko; Email: [email protected] • Mozart: Concerto in G Major or D Major, K. 313 or K. 314 (Movements I and II) • A 19th- or 20th-century French work from Flute Music by French Composers or equivalent • An unaccompanied 20th- or 21st-century work • Five orchestral excerpts from Baxtresser, Orchestral Excerpts for Flute, or equivalent • Sight reading Oboe Faculty: Emily Hart; Email: [email protected] • Choose two from the following: ◦ Saint-Saëns or Poulenc sonata (Movement I) ◦ Mozart or Haydn concerto (Movement III) ◦ Any Telemann or Vivaldi concerto or sonata (Movements I and II) ◦ Britten Six Metamorphoses (any three movements) • Choose two of the following orchestral excerpts (all excerpts may be found in the Rothwell books, Difficult Passages, published by Boosey and Hawkes): ◦ Brahms: Violin Concerto (slow movement excerpt) ◦ Rossini: La Scala di Seta (slow and fast excerpts) ◦ Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) ◦ Prokofiev: Symphony No. 1 (excerpts from Movements III and IV) • Sight reading Clarinet Faculty: Eric Ginsberg; Email: [email protected] • Choose two movements from one of the following: ◦ Mozart: Concerto in A Major, K. 622 ◦ Weber: Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. -

Cellist Zuill Bailey with Helen Kim and the KSU Symphony Orchestra

SCHOOL of MUSIC where PASSION is Zuill Bailey,heard Cello featuring Helen Kim, Violin Robert Henry, Piano KSU Symphony Orchestra Nathaniel F. Parker, Music Director and Conductor Wednesday, October 9, 2019 | 8:00 PM Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall musicKSU.com 1 heard Program LUKAS FOSS (1922-2009) CAPRICCIO MAX BRUCH (1838-1920) KOL NIDREI, OPUS 47 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893) VARIATIONS ON A ROCOCO THEME, OPUS 33 Zuill Bailey, Cello Robert Henry, Piano –INTERMISSION– JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) CONCERTO FOR VIOLIN, CELLO, AND ORCHESTRA IN A MINOR, OPUS 102 I. ALLEGRO II. ANDANTE III. VIVACE NON TROPPO Zuill Bailey, Cello Helen Kim, Violin Kennesaw State University Symphony Orchestra Nathaniel F. Parker, Conductor We welcome all guests with special needs and offer the following services: easy access, companion seating locations, accessible restrooms, and assisted listening devices. Please contact a patron services representative at 470-578-6650 to request services. 2 Kennesaw State University School of Music KSU Symphony Orchestra Personnel Nathaniel F. Parker, Music Director & Conductor Personnel listed alphabetically to emphasize the importance of each part. Rotational seating is used in all woodwind, brass, and percussion sections. Flute Violin Cello Don Cofrancesco Melissa Ake^, Garrett Clay Lorin Green concertmaster Laci Divine Jayna Burton Colin Gregoire^, principal Oboe Abigail Carpenter Jair Griffin Emily Gunby Robert Cox^ Joseph Grunkmeyer, Robert Simon Mary Catherine Davis associate principal -

Franz Anton Hoffmeister’S Concerto for Violoncello and Orchestra in D Major a Scholarly Performance Edition

FRANZ ANTON HOFFMEISTER’S CONCERTO FOR VIOLONCELLO AND ORCHESTRA IN D MAJOR A SCHOLARLY PERFORMANCE EDITION by Sonja Kraus Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2019 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Emilio Colón, Research Director and Chair ______________________________________ Kristina Muxfeldt ______________________________________ Peter Stumpf ______________________________________ Mimi Zweig September 3, 2019 ii Copyright © 2019 Sonja Kraus iii Acknowledgements Completing this work would not have been possible without the continuous and dedicated support of many people. First and foremost, I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to my teacher and mentor Prof. Emilio Colón for his relentless support and his knowledgeable advice throughout my doctoral degree and the creation of this edition of the Hoffmeister Cello Concerto. The way he lives his life as a compassionate human being and dedicated musician inspired me to search for a topic that I am truly passionate about and led me to a life filled with purpose. I thank my other committee members Prof. Mimi Zweig and Prof. Peter Stumpf for their time and commitment throughout my studies. I could not have wished for a more positive and encouraging committee. I also thank Dr. Kristina Muxfeldt for being my music history advisor with an open ear for my questions and helpful comments throughout my time at Indiana University. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ.