Sustainable Funding for Expanded Time in Public Schools (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizen Schools

A REPORT ON THE FOUNDATION’S INVESTMENTS 2000–2014 By Anne Mackinnon february 2015 Citizen Schools Reaching for Scale and National Impact Citizen Schools was created in 1995 with a vision for giving middle school students a radically new kind of afterschool experience. Unlike conventional programs, which simply kept kids busy and gave them a place to do their homework, Citizen Schools engaged participants in a dynamic program of intensive, hands-on learning activities, or “apprenticeships,” led by a combination of energetic, motivated staff and knowledgeable volunteers, or “citizen teachers.” To founders Eric Schwarz and Ned Rimer, the out-of-school-time hours were an immense resource for educating young people and building community, particularly in low-income neighborhoods. Their goal was to put those valuable hours to use. The model caught on in Boston, and Citizen At about that time, Eric Schwarz, Citizen Schools’ Schools grew steadily in its first five years. By executive director, got an unexpected call from spring 2000, the organization was serving a representative of the Edna McConnell Clark approximately 400 young people, ages 9–14, at 11 Foundation. “We’re intrigued by what you’re locations around the city. The curriculum had doing,” the caller explained, “and want to get been carefully designed, tested, and codified, and to know you better. We can’t promise anything, the training program for staff and volunteers had but if we like what we see, we might move fairly evolved into a formal “teaching fellows” initiative. quickly on a significant investment.” Nationally, Citizen Schools’ distinctive model was In May 2000, the foundation made its first grant beginning to attract attention. -

Orchard Gardens K-8 Pilot School

Transforming Schools through Orchard Gardens K–8 Pilot School Expanded Update 2013 Learning Time For years, Orchard Gardens K–8 Pilot School was plagued by low student achievement and high staff turnover. Then, in 2010, with an expanded school schedule made possible through federal funding, Orchard Gardens began a remarkable turnaround. Today, the school is demonstrating how increased learning time, combined with other key turnaround strategies, can dramatically improve the performance of even the nation’s most troubled schools. This case study, the first in a new series, takes you inside the transformation of Orchard Gardens. 1 About the Series Policymakers and educators across the country are As momentum is growing for schools to expand their grappling with the compelling challenge of how calendar to promote positive change, a new question to reform our nation’s underperforming schools and is emerging for the education field: How can schools better prepare all American students—especially that are undergoing major turnaround efforts maximize those living in poverty—for long-term success. In 2009, the great potential of expanded time? To explore the President Barack Obama and Secretary of Education answer to this question, the National Center on Time & Arne Duncan set out an ambitious effort intended to Learning has launched Transforming Schools through spur dramatic improvement among persistently low- Expanded Learning Time, a series of case studies performing schools by infusing over $3.5 billion into the examining schools that have increased learning time School Improvement Grant (SIG) program. as part of a comprehensive school turnaround and are showing promising early results. -

Restarting and Reinventing School: Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond

Restarting and Reinventing School Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond Linda Darling-Hammond, Abby Schachner, and Adam K. Edgerton in collaboration with Aneesha Badrinarayan, Jessica Cardichon, Peter W. Cookson Jr., Michael Griffith, Sarah Klevan, Anna Maier, Monica Martinez, Hanna Melnick, Natalie Truong, and Steve Wojcikiewicz AUGUST 2020 Restarting and Reinventing School: Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond Linda Darling-Hammond, Abby Schachner, and Adam K. Edgerton in collaboration with Aneesha Badrinarayan, Jessica Cardichon, Peter W. Cookson Jr., Michael Griffith, Sarah Klevan, Anna Maier, Monica Martinez, Hanna Melnick, Natalie Truong, and Steve Wojcikiewicz Acknowledgments The authors thank our Learning Policy Institute colleagues Roberta Furger, Janel George, Tara Kini, Melanie Leung, and Patrick Shields for their support, contributions, and thought partnership. In addition, we thank Erin Chase and Aaron Reeves for their editing and design contributions to this project and the entire LPI communications team for its invaluable support in developing and disseminating this report. Without their generosity of time and spirit, this work would not have been possible. This research was supported by the S. D. Bechtel Jr. Foundation, the Stuart Foundation, and the W. Clement and Jessie V. Stone Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. We are grateful to them for their generous -

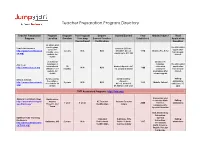

Teacher Preparatory Program

Teacher Preparation Program Directory Teacher Preparatory Program Program Post-Program Degree Stipend Earned Year Grade/Subject Next Program Location Duration Teaching Earned/Teacher Established Application Commitment Certification Deadline 46 urban and rural regions The 2013-2014 Teach for America Salary of $25,500 - across the application http://www.teachforameri 2 years N/A N/A $51,000 + AC ed. 1990 Grades Pre-K-12 country – see has already award up to $11,100 ca.org/ website for closed. details 21 national Grades 3-9: locations, 2 Tutoring, The 2013-2014 City Year international 10 Modest stipend + AC classroom application http://www.cityyear.org N/A N/A 1988 affiliates – see months ed. award of $5,550 assistance has already website for mentoring, after closed. details school support Rolling Citizen Schools 8 states across $1,900 monthly the nation – stipend + admissions http://www.citizenschools. 2 years N/A N/A 1995 Middle School see website for AC ed. award of until June 15, org/ details $5,500 for each year 2013 TNTP Associated Programs: http://tntp.org/ Elementary and Arizona Teaching Fellows Northeastern Secondary Math, Rolling http://arizonateachingfell Arizona, AZ Teacher Arizona Teacher 1 year 3 years 2008 Science, admissions ows.ttrack.org/ Phoenix, and Certification Salary Language Arts, Yuma Special Education ECE, Elementary Education, Baltimore City Teaching Special Standard Baltimore City Rolling Residency Education, Baltimore, MD 2 years N/A Professional Public Schools 1997 admissions http://bcteachingresiden Secondary -

Summer Opportunities in Education

Summer Opportunities in Education Generation Teach Denver, CO; Providence, RI; Boston, MA; Western MA https://www.generationteach.org/teach/#teach-this-summer Teach middle-school math, engineering, reading, or social studies; design and teach fitness, language, humanities, or STEM electives; co-lead fun events and community meetings during our 4- or 5-week GT STEAM Academy. Includes 2 weeks of pre-training in identity, relationships, instructional practices, and content-area pedagogy while building a community of colleagues, practicing teaching, and preparing to meet your students. Receive daily feedback and support from your Teacher Coach and a taxable scholarship to offset living costs. No prior teaching experience is required. Breakthrough Collaborative Multiple locations https://www.breakthroughcollaborative.org/apply-teacher/ The Breakthrough teaching fellow experience is designed for undergraduates of all majors and for those who intend to pursue careers in education, as well as those who haven’t yet considered it. The opportunity is unlike any other available to undergraduates and our alumni are transformed by the experience. Education coursework is not a prerequisite. We seek applicants with a deep interest in social justice and a passion for working with students. Our teaching fellows must be committed to personal growth and comfortable working in a fast- paced, collaborative environment. Because we celebrate the diversity of our community, we seek undergraduate applicants from diverse backgrounds and life experiences. During the nine- week residency, Breakthrough teaching fellows receive over 100 hours of teaching and leadership training, and 75 hours of lead classroom experience. StudentU Durham, NC http://studentudurham.org/job-openings Student U is a college-access organization that believes all students in Durham have the ability to succeed. -

Citizen Schools Skoll Awardee Profile

Citizen Schools Skoll Awardee Profile Organization Overview Key Info Social Entrepreneur Eric Schwarz Year Awarded 2005 Issue Area Addressed Education Sub Issue Area Addressed Early Childhood to Primary Education, Women's and Girls' Education, Youth Job Skills Countries Served USA Website http://www.citizenschools.org Twitter handle cschools Facebook http://www.facebook.com/CitizenSchools Youtube http://www.youtube.com/user/citizenschoolso nline About the Organization For nearly 25 years, Citizen Schools has been a pioneer in educational equity. Since opportunity, unlike talent, is not equally distributed, the organization has provided hands-on learning experiences that ignite curiosity, build confidence and expand horizons to over 50,000 underrepresented middle school students. Together with partners including 25,000 career mentors, Citizen Schools has exposed students to ideas and connections, helping them access even better opportunities than previous generations. Today, Citizen Schools engage underserved students in hands-on learning, in school and after school. Students in Citizen Schools programs are treated as creators and problem-solvers, not just consumers. They become scientists, artists, mathematicians, engineers, writers, and programmers. The program also applies best practices from direct service work to systems-level advancement of STEM mentorship and learning by working with communities. Impact Over the last 25 years, Citizen Schools has served over 50,000 underserved students and provided 25,000 career mentors through direct service in school and after school. This year Citizen Schools will engage 7,000 students and recruit 450 volunteers in Massachusetts, New York, California, and North Carolina. Makers + Mentors Network, a STEM initiative of Citizen Schools, partners with communities and organizations to uplift STEM mentoring and maker-centered learning as essential tools to build a stronger, more diverse workforce. -

Defense Stem Education Consortium (Dsec) Operational Elements

DEFENSE SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, ENGINEERING, AND MATHEMATICS EDUCATION CONSORTIUM Annual program review BASE-PERIOD REPORT MARCH 1, 2019—AUGUST 31, 2020 COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT AWARD NUMBER W911NF1920007 DEFENSE STEM EDUCATION CONSORTIUM COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT MANAGER (CAM) CONSORTIUM CHAIR (CC) Louie R. Lopez Angela H. Quick, EdD Director, DoD STEM Vice President Defense Laboratories and Personnel Education and Workforce Development Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research RTI International and Engineering [email protected] [email protected] CONSORTIUM MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE (CMC) Rebecca Stanley, PhD Katherine McKnight, PhD Individual Program Administrator (DSEC Element 1) Individual Program Administrator (DSEC Element 4) RTI International RTI International Joseph Wilson, PhD John Yochelson Individual Program Administrator (DSEC Element 2) Individual Program Administrator (DSEC Element 5) American Institutes for Research (AIR) Building Engineering and Science Talent (BEST) Dean Gerdeman, PhD Ed Veiga Principal Investigator (DSEC Element 2) National Math and Science Initiative (NMSI) American Institutes for Research (AIR) Erica Newton Fessia John Vavricka, JD For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Individual Program Administrator Technology (FIRST) (DSEC Elements 3 and 4) RTI International Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ...................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................... 8 DSEC STRATEGY -

Citizen Schools Catalyst Project Steerco #1

Citizen Schools Catalyst Project SteerCo #1 December 3rd, 2018 DRAFT Catalyst project meeting roadmap Project Holiday weeks Start up 1 2 3 4 5 6 break 7 8 9 10 11 Week 10/29 11/5 11/12 11/19 11/26 12/3 12/10 12/17- 1/2 1/7 1/14 1/21 1/28 beginning Today’s 1/1 meeting Nov 13th Dec 3rd Jan 16th Jan 30th Project Kickoff: SteerCo #1: SteerCo #2: SteerCo #3: • Introduce project team • Review initial assessment of attractiveness • Decide which Catalyst model to • Review final of Catalyst product pursue based on a refined view refinements to model • Review project scope, calendar, – Demand among schools and corporate partners of: strategy and financials and deliverables – Competitive and partner landscape – Attractiveness (including model (as needed) • Discuss goals of Catalyst and financials) • Discuss preliminary view on Citizen Schools’ • Align on near-term dimensions for evaluating – Fit and ability to win ability to win and fit with Catalyst product mobilization plan Catalyst (attractiveness, fit, and • Define capabilities and assets – Capabilities to build out ability to win) – Fit with capabilities and operational feasibility – Ability to scale needed to deliver strategy – Partners to engage • Align on key discussion topics for – Potential for differentiation • Review preliminary list of customer interviews (schools and partners to engage corporate partners) • Agree on set of Catalyst models, including Model 1 and Model 2, to explore in-depth BOS 181203 Catalyst Project SteerC ... 2 Objectives for today’s discussion Review initial view of demand and market opportunity for Catalyst Discuss set of potential model options for Catalyst and the strengths and risks of each model Align on major areas for further exploration for SteerCo #2 BOS 181203 Catalyst Project SteerC .. -

Helping All Kids Discover and Achieve Their Dreams

Helping all kids discover and achieve their dreams American Institutes for Research Using Research to Inform Policies and Practices in STEM Education Symposium September 2013 Citizen Schools Program Model Closing the Opportunity Gap http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=playe r_embedded&v=U1X6TyyDhO8 Enrichment Expenditure on Children by Family Income Top quartile: family income Bottom quartile: family income Source: Whither Opportunity? Duncan & Murnane, 2011 Opportunity Equation When Steve Jobs was a teenager a neighbor who worked as an engineer at Hewlett-Packard got him into the H-P Explorer's Club, a group of about 15 students that met every Tuesday evening at the company cafeteria. Jobs reflected on how this exposure to real world technology and the engineers who made it was a life-changer for him: “Every week they would get an engineer from one of the labs to come and talk with us about what he or she was working on. My dad would drive me there. I was in heaven.’” Making Systems That Work for Students “When we look at the positive deviants – the hospitals who are getting the best results at the lowest costs -- we find the ones that look most like systems are most successful. They found ways to get all the pieces to come together into a whole. … Making systems work, whether in health care, education, climate change, or pathways out of poverty, is the great task of our generation. In every field, knowledge has exploded, but it has Typical hospital visit: brought complexity, it has brought specialization. We have no choice but to recognize, as In 1970 1 patient interacts individualistic as we want to be, complexity with 2 medical professionals requires group success. -

Moving Education Forward: Strengthening STEM in Today's Classrooms

Moving Education Forward: Strengthening STEM in Today's Classrooms = hA (Tw-T∞) = hA (∆T) (w << t) Vm = 1-Vf -sc < {s1, s2} < st 100 10010100100 101001000101001010101010010101010 0101001 01 10010 101 10 1010010101010101010010101010101 010101 0101001010 101010 01 010 01010100101010101010101 H2O CO3(aq) → H2O(l) + CO2(g) 2KClO3(s) → 2KCl(s) + 3O2(g) Na- 2S2O3 + I2 Hydrocarbon (CxHy) + O2(g) → CO2(g) + H2O(g) H2, N2, O2, =y2 MgO + H2O Mg(OH) NaOH + LiF --> NaF + 4LiOH Mg + (s) (l) → 2(s) - + CuF₂ ₂ Cu + MgF₂ OH NH₂ Fe{3+} + I{-} = 2 2 2 a + b = c 6.78930% X 4.596? 2.4/567 y=mx+b -2.4X∆ √3.456(7.6)3 3%(∏x2) = y ∑ 2.39/7.89(x) = 0 14+r2(-.893) y/8.14 = ? 7.34%x(894) = 5 6.45/2 d=4.253 3.2145/9 = x + 35 100 10010100100 101001000101001010101010010101010 0101001 01 10010 101 10 1010010101010101010010101010101 010101 0101001010 101010 01 010 01010100101010101010101 Moving Education Forward: Strengthening STEM in Today's Classrooms Company Name (more than 1 pg) 1 2 Strengthening STEM in Today’s Classrooms Participating Companies Company Name (more than 1 pg) 3 4 Strengthening STEM in Today’s Classrooms Table of Contents A Message From ITI President and CEO Dean C. Garfield 7 Facing STEM Challenges 9 STEM: A Key to Innovation 11 Forging New, Deeper Partnerships between Business 13 & Higher Education Accenture 17 Adobe 19 Alcatel-Lucent 21 Applied Materials 23 Autodesk 29 CA Technologies 33 Cognizant 39 EMC 45 Ericsson 49 Google 51 HP 55 IBM 61 Micron 65 Microsoft 69 NCR 75 Oracle 79 Qualcomm 85 Symantec 89 Teradata 93 Texas Instruments 97 Index 102 Company Name (more than 1 pg) 5 6 Strengthening STEM in Today’s Classrooms A Message From ITI President and CEO Dean C. -

Citizen Schools Catalyst Project Steerco #2

Citizen Schools Catalyst Project SteerCo #2 January 16th, 2019 DRAFT Catalyst project meeting roadmap Project Holiday weeks Start up 1 2 3 4 5 6 break 7 8 9 10 11 Week 10/29 11/5 11/12 11/19 11/26 12/3 12/10 12/17- 1/2 1/7 1/14 1/21 1/28 beginning 1/1 Today’s meeting Nov 13th Dec 3rd Jan 16th Jan 30th Project Kickoff: SteerCo #1: SteerCo #2: SteerCo #3: • Introduce project team • Review initial assessment of attractiveness • Review refined assessment of • Review final of Catalyst product attractiveness of Catalyst refinements to Catalyst • Review project scope, calendar, – Demand among schools and corporate partners product model strategy and and deliverables – Competitive and partner landscape financials (as needed) • Discuss which Catalyst model • Discuss goals of Catalyst and • Discuss preliminary view on Citizen Schools’ to pursue based on a refined • Align on near-term dimensions for evaluating ability to win and fit with Catalyst product view of: mobilization plan Catalyst (attractiveness, fit, and – Attractiveness (including model – Capabilities to build out ability to win) – Fit with capabilities and operational feasibility – Ability to scale financials) • Align on key discussion topics for – Potential for differentiation – Fit and ability to win customer interviews (schools and corporate partners) • Agree on set of Catalyst models, including Model 1 and Model 2, to explore in-depth BOS 190116 Catalyst Project SteerC ... 2 Objectives for today’s discussion Review refined view of demand for Catalyst among customers Discuss preliminary scale projections and economic model analysis Debate which Catalyst model to pursue based on attractiveness, fit, & ability to win Align on major areas for further refinement for SteerCo #3 BOS 190116 Catalyst Project SteerC .. -

Expanding Learning Time

Expanding Learning Time How the Edwards Middle School in Boston partnered with Citizen Schools to transform the learning day by KATE CARPENTER BERNIER APRIL 2 0 0 8 "There are few more promising strategies for helping all children get ahead in today’s global economy than expanding learning time. It gives students the time not only to master the basics, but also to expand their horizons through art, music, physical education and other activities. It gives teachers additional time for collaboration and planning to improve instruction. The early results of the Expanded Learning Time Initiative here in Massachusetts are impressive and show real promise in preparing all children for a lifetime of success. I believe what we’re doing with expanded learning here in Massachusetts is a model for the nation." SENATOR EDWARD KENNEDY EDWARDS MIDDLE SCHOOL JANUARY 9, 2008 Expanding Learning Time How the Edwards Middle School in Boston partnered with Citizen Schools to transform the learning day Edwards Middle School and Citizen Schools Introduction EXPANDING LEARNING TIME in schools, particularly for students from low-income communities, is gaining currency in the education reform move- ment. Senator Edward Kennedy and Congressman George Miller, the commit- tee leaders in charge of reauthorizing the No ize school funding, and increase choice and Child Left Behind Act (nclb), are both pushing innovation. State and national reforms of recent large demonstration programs to expand learn- decades did help increase and equalize funding, ing time as part of their reauthorization designs. and clarify and raise standards and account- In philanthropy, the $60 million “ED in ‘08” ability.