Restarting and Reinventing School: Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizen Schools

A REPORT ON THE FOUNDATION’S INVESTMENTS 2000–2014 By Anne Mackinnon february 2015 Citizen Schools Reaching for Scale and National Impact Citizen Schools was created in 1995 with a vision for giving middle school students a radically new kind of afterschool experience. Unlike conventional programs, which simply kept kids busy and gave them a place to do their homework, Citizen Schools engaged participants in a dynamic program of intensive, hands-on learning activities, or “apprenticeships,” led by a combination of energetic, motivated staff and knowledgeable volunteers, or “citizen teachers.” To founders Eric Schwarz and Ned Rimer, the out-of-school-time hours were an immense resource for educating young people and building community, particularly in low-income neighborhoods. Their goal was to put those valuable hours to use. The model caught on in Boston, and Citizen At about that time, Eric Schwarz, Citizen Schools’ Schools grew steadily in its first five years. By executive director, got an unexpected call from spring 2000, the organization was serving a representative of the Edna McConnell Clark approximately 400 young people, ages 9–14, at 11 Foundation. “We’re intrigued by what you’re locations around the city. The curriculum had doing,” the caller explained, “and want to get been carefully designed, tested, and codified, and to know you better. We can’t promise anything, the training program for staff and volunteers had but if we like what we see, we might move fairly evolved into a formal “teaching fellows” initiative. quickly on a significant investment.” Nationally, Citizen Schools’ distinctive model was In May 2000, the foundation made its first grant beginning to attract attention. -

The Role of Emotion and Skilled Intuition in Learning

Mary Helen Immordino-Yang Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, EdD, is a cognitive neuroscientist and educational psychologist who studies the brain bases of emotion, social interaction, and culture and their implications for development and schools. A former junior high school science teacher, she earned her doctor- ate at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education. She is the associate North American editor for the journal Mind, Brain and Education and the inaugural recipient of the International Mind, Brain and Education Society’s Award for Transforming Education through Neuroscience. She is currently Assistant Professor of Education at the Rossier School of Education and Assistant Professor of Psychology at the Brain and Creativity Institute, University of Southern California. Matthias Faeth Matthias Faeth is a doctoral student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. His interest is the interaction of emotions and learning from an educational, psychologi- cal, and neuroscientific perspective. He is currently living in Montreal where he is also pursuing his research at the Centre de Recherché en Neuropsychologie et Cognition (CERNEC) at the Université de Montréal. In this chapter, the authors present a neuroscientific view of how emotions affect learning new information and suggest a set of socially embedded educational practices that teachers can use to improve the emotional and cognitive aspects of classroom learning. 66 Chapter 4 The Role of Emotion and Skilled Intuition in Learning Mary Helen Immordino-Yang and Matthias Faeth Advances in neuroscience have been increasingly used to inform educational theory and practice. However, while the most successful strides forward have been made in the areas of academic disciplinary skills such as reading and mathematical processing, a great deal of new evidence from social and affective neuroscience is prime for application to education (Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2007; Immordino-Yang & Fischer, in press). -

Meaningful Learning CHAPTER 1 Shutterstock

M01_HOWL5585_04_SE_C01.qxd 2/11/11 10:00 PM Page 1 Goal of Technology Integrations: Meaningful Learning CHAPTER 1 Shutterstock Chapter Objectives 1. Identify the characteristics of meaningful learning 4. Describe how technology can foster 21st Century Skills 2. Contrast learning from technology and learning with technology 5. Describe the components of technological pedagogical content knowledge 3. Compare National Educational Technology Standards (NETS) for students with teacher activities that foster them M01_HOWL5585_04_SE_C01.qxd 2/11/11 10:00 PM Page 2 2 Chapter 1 This edition of Meaningful Learning with Technology is one of many books describing how technologies can and should be used in schools. What distinguishes this book from the oth- ers is our focus on learning, especially meaningful learning. Most of the other books are organized by technology. They provide advice on how to use technologies, but often the purpose for using those technologies is not explicated. Meaningful Learning with Technology, on the other hand, is organized by kinds of learning. What drives learning, more than anything else, is understanding and persisting on some task or activity. The nature of the tasks best determines the nature of the students’ learning. Unfortunately, the nature of the tasks that so many students most commonly experience in schools is completing standardized tests or memorizing infor- mation for teacher-constructed tests. Schools in the United States have become testing factories. Federal legislation (No Child Left Behind) has mandated continuous testing of K–12 students in order to make schools and students more accountable for their learn- ing. In order to avoid censure and loss of funding, many K–12 schools have adopted test preparation as their primary curriculum. -

Orchard Gardens K-8 Pilot School

Transforming Schools through Orchard Gardens K–8 Pilot School Expanded Update 2013 Learning Time For years, Orchard Gardens K–8 Pilot School was plagued by low student achievement and high staff turnover. Then, in 2010, with an expanded school schedule made possible through federal funding, Orchard Gardens began a remarkable turnaround. Today, the school is demonstrating how increased learning time, combined with other key turnaround strategies, can dramatically improve the performance of even the nation’s most troubled schools. This case study, the first in a new series, takes you inside the transformation of Orchard Gardens. 1 About the Series Policymakers and educators across the country are As momentum is growing for schools to expand their grappling with the compelling challenge of how calendar to promote positive change, a new question to reform our nation’s underperforming schools and is emerging for the education field: How can schools better prepare all American students—especially that are undergoing major turnaround efforts maximize those living in poverty—for long-term success. In 2009, the great potential of expanded time? To explore the President Barack Obama and Secretary of Education answer to this question, the National Center on Time & Arne Duncan set out an ambitious effort intended to Learning has launched Transforming Schools through spur dramatic improvement among persistently low- Expanded Learning Time, a series of case studies performing schools by infusing over $3.5 billion into the examining schools that have increased learning time School Improvement Grant (SIG) program. as part of a comprehensive school turnaround and are showing promising early results. -

ADVANCE UNCORRECTED COPY—NOT for DISTRIBUTION Learning That Sticks

In far too many classrooms, the emphasis is on instructional strategies that teachers employ rather than on what students should be doing or thinking about as part of their learning. What’s more, students’ minds are something of a mysterious “black box” for most teachers, so when learning breaks down, they’re not sure what went wrong or what to do differently to help students learn. It doesn’t have to be this way. Learning That Sticks helps you look inside that black box. Bryan Goodwin and his coauthors unpack the cognitive science underlying research-supported learning strategies so you can sequence them into experiences that challenge, inspire, and engage your students. As a result, you’ll learn to teach with more intentionality—understanding not just what to do but also when and why to do it. By way of an easy-to-use six-phase model of learning, this book • Analyzes how the brain reacts to, stores, and retrieves new information. • Helps you “zoom out” to understand the process of learning from beginning to end. • Helps you “zoom in” to see what’s going on in students’ minds during each phase. Learning may be complicated, but learning about learning doesn’t have to be. And to that end, Learning That Sticks helps shine a light into all the black boxes in your classroom and make your practice the most powerful it can be. ADVANCE UNCORRECTED COPY—NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION learning that sticks A Brain-Based Model for K–12 Instructional Design and Delivery Preface: Why a Learning Model? ..................................................................................................vii 1. -

The Future of Retail Technology with Martin Shave – Microsoft Business Applications Industry Lead

The future of retail technology With Martin Shave – Microsoft Business Applications Industry Lead Listen to Episode How we buy things is changing. These days, you can book a cab using This pace of change affects every retailer. Even the specialists. an app, no need to make a call or talk to someone if you don’t feel Whether selling cars, clothes or washing machines. And being able like it. For a retail customer, the experience of purchasing goods has to provide a connected experience solely through an e-commerce changed because of such apps. There was already a significant shift site is a challenge. If you want to buy a new car, you may do initial to buying online, further accelerated by many shops not being open research online, but you still want to sit in the car, get a feel for it, look during the pandemic. But we are seeing the pace of change, and at the trim, play around with the seat. New technology can help with innovation, increase. this experience. Mixed reality, for example, introduces an element of interactivity. You can see a customisable 3D image of what you want to buy through an app on your phone or desktop, even down to the trim of your choice. This elevates e-commerce into something more valuable to your customer. 2 / 6 Will consumers always need an element of physical retail experience? In some cases you do want to touch, taste, or even smell (that ‘new car Beacon and proximity-based technology, and opting into apps, helps smell’) the products you are buying, so the future of commerce isn’t retailers capture customer information. -

Impact of Nutrition Education on Student Learning Lydia Singura Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 1-1-2011 Impact of Nutrition Education on Student Learning Lydia Singura Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Home Economics Commons, Human and Clinical Nutrition Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University COLLEGE OF EDUCATION This is to certify that the doctoral study by Lydia Singura has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. David Stein, Committee Chairperson, Education Faculty Dr. Nancy Walters, Committee Member, Education Faculty Dr. Robert Hogan, University Reviewer, Education Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2013 Abstract Impact of Nutrition Education on Student Learning by Lydia Singura MA, Kean University, 1995 BS, James Madison University, 1968 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education Teacher Leadership Walden University October 2013 Abstract A goal of schools is to provide students with practical nutritional information that will foster healthy lifelong behaviors. Unfortunately, students at one school were found to have difficulty grasping basic nutritional information and practical health-related skills. There remains an important gap in current literature regarding strategies to improve students’ understanding of nutrition education material. -

Microsoft Book of News in Deutsch

Book of News Microsoft Ignite 2020 Deutsche Microsoft Book of News in Deutsch NOTE: PDF translations for the Book of News are now available to assist in reading content in languages other than English. Please note that translations may not always be exact and should be used as an approximation of the original English language content. Ein Vorwort von Frank Shaw : Was ist das Book of News? 1. Azure 1.1 Azure KI 1.1.1 Azure Cognitive Search-Updates: Private Endpoints und Managed Identities 1.1.2 Azure Cognitive Services-Updates: Metrics Advisor-Vorschau, Spatial Analysis- Vorschau, Anomaly Detector GA 1.1.3 Azure Machine Learning-Updates: Designer, Automated ML GA und mehr 1.1.4 Microsoft Bot Framework- und Azure Bot Service-Updates 1.2 Azure Data 1.2.1 Azure Cache for Redis bietet Entwicklern zwei neue Produktebenen, um neue Anwendungsfälle freizuschalten und Caches zu verbessern 1.2.2 Azure Cosmos DB bietet jetzt eine serverlose Option für Datenbankoperationen mit geringen Workloads 1.2.3 Azure Database for MySQL und Azure Database for PostgreSQL bieten flexible Server-Bereitstellungsoption zur Verbesserung von Auswahl, Leistung und Skalierbarkeit 1.2.4 Azure SQL erweitert die Zonenredundanz auf Allzweckdatenbanken, um die Robustheit zu erhöhen 1.2.5 Azure SQL Edge, optimiert für IoT-Gateways und -Geräte, ist jetzt allgemein verfügbar 1.2.6 Nutzungsbasierte Optimierung mit Azure Synapse und Power BI 1 1.2.7 Ankündigung der Vorschau von Photon-betriebenen Delta Engine for Azure Databricks zur Beschleunigung großer Daten- und KI-Workloads -

Retrieval-Based Learning: a Perspective for Enhancing Meaningful Learning

Educ Psychol Rev (2012) 24:401–418 DOI 10.1007/s10648-012-9202-2 REVIEW ARTICLE Retrieval-Based Learning: A Perspective for Enhancing Meaningful Learning Jeffrey D. Karpicke & Phillip J. Grimaldi Published online: 4 August 2012 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2012 Abstract Learning is often identified with the acquisition, encoding, or construction of new knowledge, while retrieval is often considered only a means of assessing knowledge, not a process that contributes to learning. Here, we make the case that retrieval is the key process for understanding and for promoting learning. We provide an overview of recent research showing that active retrieval enhances learning, and we highlight ways researchers have sought to extend research on active retrieval to meaningful learning—the learning of complex educational materials as assessed on measures of inference making and knowledge application. However, many students lack metacognitive awareness of the benefits of practicing active retrieval. We describe two approaches to addressing this problem: class- room quizzing and a computer-based learning program that guides students to practice retrieval. Retrieval processes must be considered in any analysis of learning, and incorpo- rating retrieval into educational activities represents a powerful way to enhance learning. Keywords Retrieval . Learning . Metacognition . Meaningful learning What does it mean to say that a person has learned something? Some might say it means a learner has acquired new knowledge that now exists in his or her mind. Others might add that it means a learner has actively created a rich and elaborated knowledge structure. These ideas would tell only half the story, however, and it may not be the crucial half for understanding learning. -

A Comparative Study of Rehearsal and Loci Methods in Learning Vocabulary in EFL Context

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 5, No. 7, pp. 1451-1457, July 2015 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0507.18 A Comparative Study of Rehearsal and Loci Methods in Learning Vocabulary in EFL Context Touran Ahour Department of English, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran Sepideh Berenji Department of Public and Basic Science, Osku Branch, Islamic Azad University, Osku, Iran Abstract—Effective learning in foreign language settings depends on acquiring a large number of vocabularies. This study intended to compare two vocabulary learning methods known as loci and rehearsal methods to find out which one leads to better retention and recalling of words. Employing a quasi-experimental research, 80 learners from two intact classes in Islamic Azad University, Osku Branch, Iran, were randomly selected as the experimental and control groups. For the purpose of vocabulary learning, the experimental group trained in loci method while rehearsal strategy training was used in the control group. At the end of each session of the treatment, multiple-choice vocabulary tests were used to measure whether the participants can recall the lexical items from their short-term memory. A delayed multiple-choice posttest of vocabulary was also used in order to compare vocabulary learning among two groups four weeks after the treatment. Implementing Independent Samples t-test, the results indicated that experimental group was better than control group in retention and recalling of lexical items in immediate posttest. It was also found that the loci method was more effective than rehearsal in permanency of lexical items in long term memory. -

Effect of a Brain-Based Learning Program on Working Memory and Academic Motivation Among Tenth Grade Omanis Students

EFFECT OF A BRAIN-BASED LEARNING PROGRAM ON WORKING MEMORY AND ACADEMIC MOTIVATION AMONG TENTH GRADE OMANIS STUDENTS Abstract: This study aims to investigate the effect of a brain- Adel M. ElAdl, PhD based learning program on working memory and academic Full Professor of Educational Psychology motivation among tenth grade Omanis students. The sample Sultane Qaboos University was selected from students in the tenth grade in basic education Oman in the Sultanate of Oman. The participants in this study were 75 Contact: preparatory school students. Experimental group (EG) E-mail: [email protected] consisted of 37 students while the control group (CG) consisted of 38 students. An experimental Pretest and Posttest Control- Mourad Ali Eissa Saad, PhD Group design was used in this study. The brain-based learning Full Professor of Special Education program was conducted to the whole class by their actual Vice president of KIE University teacher during the actual lesson period for 8 weeks with 50 Kie University minute sessions conducted three times a week. The program Egypt was designed based on the three basic fundamentals of brain- Contact: based learning, namely ‘orchestrated immersion’, ‘relaxed E-mail: [email protected] alertness’, and ‘active processing’. The results of this study indicated great gains for students in the experimental group in both working memory and academic motivation. This study goes some way to understanding working memory and academic motivation in Omanis tenth grade primary students.The study shows that students in the experimental group, compared to those in the control group, develop robust working memory and academic motivation due to training in brain-based learning. -

Teacher Preparatory Program

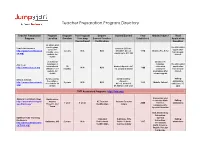

Teacher Preparation Program Directory Teacher Preparatory Program Program Post-Program Degree Stipend Earned Year Grade/Subject Next Program Location Duration Teaching Earned/Teacher Established Application Commitment Certification Deadline 46 urban and rural regions The 2013-2014 Teach for America Salary of $25,500 - across the application http://www.teachforameri 2 years N/A N/A $51,000 + AC ed. 1990 Grades Pre-K-12 country – see has already award up to $11,100 ca.org/ website for closed. details 21 national Grades 3-9: locations, 2 Tutoring, The 2013-2014 City Year international 10 Modest stipend + AC classroom application http://www.cityyear.org N/A N/A 1988 affiliates – see months ed. award of $5,550 assistance has already website for mentoring, after closed. details school support Rolling Citizen Schools 8 states across $1,900 monthly the nation – stipend + admissions http://www.citizenschools. 2 years N/A N/A 1995 Middle School see website for AC ed. award of until June 15, org/ details $5,500 for each year 2013 TNTP Associated Programs: http://tntp.org/ Elementary and Arizona Teaching Fellows Northeastern Secondary Math, Rolling http://arizonateachingfell Arizona, AZ Teacher Arizona Teacher 1 year 3 years 2008 Science, admissions ows.ttrack.org/ Phoenix, and Certification Salary Language Arts, Yuma Special Education ECE, Elementary Education, Baltimore City Teaching Special Standard Baltimore City Rolling Residency Education, Baltimore, MD 2 years N/A Professional Public Schools 1997 admissions http://bcteachingresiden Secondary