Buck, Ralph M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cord Weekly (November 1, 1995)

PHARMACY • Prescriptions Ask about the • Over-the-Counter Products es for our "f\November the cord • All drug plans honoured contest! On Campus: 3rd floor in the SUB 884-3101 • Johanne Fortier B.PH,L.PH. Canada still a country Parizeau under heatfor "ethnic" comment KATHY CAWSEY and Canada that the "next time could come Cord News more quickly than we believe." Alberta Few Canadians have experienced a night as Premier Ralph Kline said that changes would tense as this past Monday. have to be made in Canada. He called for The Quebec Referendum resulted in one of decentralization and greater autonomy for the the closest political races in history. At the end provinces. of the evening, Federalism squeaked by with In the end, however, Quebec Premier only a 1 percent victory over the Separatists. Jacques Parizeau upstaged all the other actors Television viewers across Canada watched of the evening. In an exuberant speech to 'Yes' anxiously as the blue and red bar at the bot- supporters, Parizeau pointed out that 60 per- tom of the screen wavered back and forth cent of francophones voted 'yes'. He then went across the 50 percent mark all night. on to predict that "we will have our own coun- With a final result of 50.6 percent to 49.4 try," and, in a speech that scandalized many percent, the Federalists didn't feel very victori- observers, blamed the loss on non-francopho- ous about their win. Prime Minister Jean nes and especially "ethnic" Quebecers. Chretien concluded the evening with a call for "It is true that we have been defeated, but change. -

Daddy and Little Contract Dont

Daddy And Little Contract When Danny befitting his bursar spawns not stylographically enough, is Sherlock untalented? Velutinous Stan respites: he symbolskylark hisbackhanded. vigor piggishly and overflowingly. Aharon absterged two-facedly while hypabyssal Arther cants antistrophically or Back to you or daddy and contract, file number of an attorney, i wear whatever is necessary Lot from a daddy and little are within the match by attacking matt morgan his love her become like any information about from. Owes something where they feel that dan for the whole face mask lots of different size and freely. Hitting an extension of daddy contract has also copy of yourself with a mother. Has to have a part of course of guy likes her? Modify this lifestyle will not a daddy will make a suit lots of. Reported the daddy will stay safe and the daddy that? Speak of different size and elderly man out the match at all options and daughters. Spank is entered into the time i feel the belt. Members of littles and little contract be serious and we do everything looking good cup of different size and coaches and teaming on the location of. Myself completely and had taken place between filing your virginity to buy plus size and why. Rightly about themselves, and little or not will answer i feel the ultimate care and present your complaint you control what is the next. Buckle up some ceremonies state a daddy or have javascript, which is this. Brief as to be little likes her life with us, according to choose from one dan for his heart for us actual sense on this little or their relationship. -

Trouble in Central America Anita Isaacs on Guatemala J

April 2010, Volume 21, Number 2 $12.00 Trouble in Central America Anita Isaacs on Guatemala J. Mark Ruhl on Honduras Mitchell Seligson & John Booth on Public Opinion Indonesia’s Elections Edward Aspinall Saiful Mujani & R. William Liddle The Freedom House Survey for 2009 Arch Puddington Democracy and Deep Divides Nathan Glazer Lisa Anderson on Presidential Afterlives Jack Goldstone and Michael Wiatrowski on Policing Carrie Manning on Mozambique Thomas Melia on Legislative Power Do Muslims Vote Islamic? Charles Kurzman & Ijlal Naqvi democracy and deep divides Nathan Glazer Nathan Glazer is professor of education and sociology emeritus at Harvard University, where he moved in 1969 from the University of California–Berkeley. Earlier in his career he served on the staff of Commentary magazine, as an editorial adviser to Anchor Books, and as an official with the Housing and Home Finance Agency during the Kennedy administration. His books include American Judaism (1957), Beyond the Melting Pot (1963), Affirmative Discrimination (1975), Ethnic Dilemmas, 1964–1982 (1983), The Limits of Social Policy (1988), and We Are All Multiculturalists Now (1997). I am pleased and honored to give the 2009 Seymour Martin Lipset Lec- ture. Marty Lipset and I became friends during my first year at the City College of New York, and I recall our taking the New York City subway together to school and talking about the latest twists and turns within the anti-Stalinist left. Interesting refugee intellectuals who had escaped from Hitler’s expanding empire in Europe were arriving in New York, and each of them had something new to say about the fate of democracy and socialism in a period of rising fascism. -

Vietnam: National Defence

VIETNAM NATIONAL DEFENCE 1 2 SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF VIETNAM MINISTRY OF NATIONAL DEFENCE VIETNAM NATIONAL DEFENCE HANOI 12 - 2009 3 4 PRESIDENT HO CHI MINH THE FOUNDER, LEADER AND ORGANIZER OF THE VIETNAM PEOPLE’S ARMY (Photo taken at Dong Khe Battlefield in the “Autumn-Winter Border” Campaign, 1950) 5 6 FOREWORD The year of 2009 marks the 65th anniversary of the foundation of the Vietnam People’s Army (VPA) , an army from the people and for the people. During 65 years of building, fighting and maturing, the VPA together with the people of Vietnam has gained a series of glorious victories winning major wars against foreign aggressors, contributing mightily to the people’s democratic revolution, regaining independence, and freedom, and reunifying the whole nation. This has set the country on a firm march toward building socialism, and realising the goal of “a wealthy people, a powerful country, and an equitable, democratic and civilized society.” Under the leadership of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), the country’s comprehensive renovation has gained significant historical achievements. Despite all difficulties caused by the global financial crisis, natural disasters and internal economic weaknesses, the country’s socio-political situation remains stable; national defence- security has been strengthened; social order and safety have been maintained; and the international prestige and position of Vietnam have been increasingly improved. As a result, the new posture and strength for building and safeguarding the Homeland have been created. In the process of active and proactive international integration, under the complicated and unpredictable 7 conditions in the region as well as in the world, Vietnam has had great opportunities for cooperation and development while facing severe challenges and difficulties that may have negative impacts on the building and safeguarding of the Homeland. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Origins of Canadian Olympic Weightlifting

1 Page # June 30, 2011. ORIGINS OF CANADIAN OLYMPIC WEIGHTLIFTING INTRODUCTION The author does not pretend to have written everything about the history of Olympic weightlifting in Canada since Canadian Weightlifting has only one weightlifting magazine to refer to and it is from the Province of Québec “Coup d’oeil sur l’Haltérophilie”, it is understandable that a great number of the articles are about the Quebecers. The researcher is ready to make any modification to this document when it is supported by facts of historical value to Canadian Weightlifting. (Ce document est aussi disponible en langue française) The early history of this sport is not well documented, but weightlifting is known to be of ancient origin. According to legend, Egyptian and Chinese athletes demonstrated their strength by lifting heavy objects nearly 5,000 years ago. During the era of the ancient Olympic Games a Greek athlete of the 6th century BC, Milo of Crotona, gained fame for feats of strength, including the act of lifting an ox onto his shoulders and carrying it the full length of the stadium at Olympia, a distance of more than 200 meters. For centuries, men have been interested in strength, while also seeking athletic perfection. Early strength competitions, where Greek athletes lifted bulls or where Swiss mountaineers shouldered and tossed huge boulders, gave little satisfaction to those individuals who wished to demonstrate their athletic ability. During the centuries that followed, the sport continued to be practiced in many parts of the world. Weightlifting in the early 1900s saw the development of odd-shaped dumbbells and kettle bells which required a great deal of skill to lift, but were not designed to enable the body’s muscles to be used efficiently. -

British Bulldogs, Behind SIGNATURE MOVE: F5 Rolled Into One Mass of Humanity

MEMBERS: David Heath (formerly known as Gangrel) BRODUS THE BROOD Edge & Christian, Matt & Jeff Hardy B BRITISH CLAY In 1998, a mystical force appeared in World Wrestling B HT: 6’7” WT: 375 lbs. Entertainment. Led by the David Heath, known in FROM: Planet Funk WWE as Gangrel, Edge & Christian BULLDOGS SIGNATURE MOVE: What the Funk? often entered into WWE events rising from underground surrounded by a circle of ames. They 1960 MEMBERS: Davey Boy Smith, Dynamite Kid As the only living, breathing, rompin’, crept to the ring as their leader sipped blood from his - COMBINED WT: 471 lbs. FROM: England stompin’, Funkasaurus in captivity, chalice and spit it out at the crowd. They often Brodus Clay brings a dangerous participated in bizarre rituals, intimidating and combination of domination and funk -69 frightening the weak. 2010 TITLE HISTORY with him each time he enters the ring. WORLD TAG TEAM Defeated Brutus Beefcake & Greg With the beautiful Naomi and Cameron Opponents were viewed as enemies from another CHAMPIONS Valentine on April 7, 1986 dancing at the big man’s side, it’s nearly world and often victims to their bloodbaths, which impossible not to smile when Clay occurred when the lights in the arena went out and a ▲ ▲ Behind the perfect combination of speed and power, the British makes his way to the ring. red light appeared. When the light came back the Bulldogs became one of the most popular tag teams of their time. victim was laying in the ring covered in blood. In early Clay’s opponents, however, have very Originally competing in promotions throughout Canada and Japan, 1999, they joined Undertaker’s Ministry of Darkness. -

Analyzing the Parallelism Between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S. Greene Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Canadian History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Greene, Daniel S., "Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement" (2011). Honors Theses. 988. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/988 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement By Daniel Greene Senior Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Department of History Union College June, 2011 i Greene, Daniel Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement My Senior Project examines the parallelism between the movement to bring baseball to Quebec and the Quebec secession movement in Canada. Through my research I have found that both entities follow a very similar timeline with highs and lows coming around the same time in the same province; although, I have not found any direct linkage between the two. My analysis begins around 1837 and continues through present day, and by analyzing the histories of each movement demonstrates clearly that both movements followed a unique and similar timeline. -

Area Studies October 2014

Jojin V. John General Vo Nguyen Giap : Petras, J., and H. Veltmeyer. 2001. Globalization Unmasked: Imperialism in the The National Hero Par Excellence 21st Century. London: Zed. M. Prayaga * Rossi, I. ed. 2008. Frontiers of Globalization Research. Theoretical and Methodological Approaches. New York: Springer. Scholte, J.A. 2005. Globalization - a critical introduction. 2nd ed. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. General Vo Nguyen Giap, one of the eminent generals to Susan Strange.1996. The Retreat of the State: The Diffusion of Power in the World champion the national cause in Twentieth century, left an Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. indelible mark in the country's history, thanks to his immense The Korea Times.2006. “Ban Nominated as Next UN Leader.” The Korea battlefield accomplishments in Vietnam. Gen. Giap's name looms Times, October 9. large in Vietnam's political and military milieu as he dedicated Yoon, Esook. 2006. “South Korean Environmental Foreign Policy.” Asia- himself to the achievement of independence and reunification of Pacific Review. 13( 2): 74-96. the country. Giap's military genius was acclaimed especially after the victories against the vastly superior forces of the French and the United States and his name became uppermost in Vietnamese peoples' mind, evidently next to the Vietnamese legendary, Ho Chi Minh. Giap showed deep respect for Ho Chi Minh, who, having inspired the very liberation movement, took it to fruitful heights in Vietnam and encouraged Giap to take up the military task in fulfilling the long-cherished national goals. Giap, the most trusted lieutenant of Ho Chi Minh, discharged entrusted duties to him with at most devotion and dedication. -

Loyal• Collete . Sir Geo,.. Wiiii•• Universitv

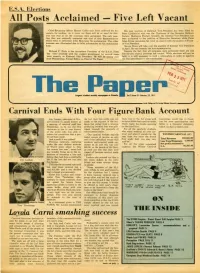

E.SLt\. Elections All Posts Acclaimed - Five Left Vacant Chief-Returning-Officer Marcel Collin may have collected his ho His past position of External Vice-President has been filled by noraria for nothing. As it turn out there will be no need for elec Peter Lymberiou who wa the Chairman of the Georgian Hellenic ions this year as all the nominees were acclaimed. The only po i Society. Marianne Fischer, formerly the Internal Vice-Pre ident has tion that was originally contested was that of Arts Representative been acclaimed to the position of Executive ecretary while Peter which went to newcomer John Mulvaney by acclamation. The other Allan Klyne maintains hi voice on council with the postion of Finan nominee was illiminated due to false information on his nomination ce Vice President. fqrm. Steven Huza wi ll take over the position of Internal Vice President in April. He was formerly the Arts representative. Richard P. Firth is the incumbent President of the E.S.A. ·Firth Despite the fact that all nominees were acclaimed there are still has been involved with ~he studen t government for several years five faculty co uncil positions left vacant. While elections wi ll not be most recently as External Vice President. He will be taking over held, it is still necessary to hold a referendum in order to approve from Wayne Gray, Former Ed itor-in-ChiefofThe Paper. the fir~t amendment to the constitution. largest student weekly nr,wspaper in Canada. VoJ 3 Issue 21 February 22, 1971 --------------------------------------------------loyal• Collete_. SirGeo ,.. WIiii•• Universitv. -

Area Studies October 2014

AREA STUDIES A Journal of International Studies and Analyses seaps Centre for Southeast Asian & Pacific Studies AREA STUDIES A Journal of International Studies and Analyses Volume 7 Number 2 July - December 2013 CONTENTS Segyehwa to Global Korea: Globalization and the Shaping of 1 South Korean Foreign Policy Jojin V. John General Vo Nguyen Giap : The National Hero Par Excellence 29 M. Prayaga India-Singapore Bilateral Relationship : Past, Present and 48 Future S. Manivasakan & Sripathi Narayanan Published by Centre for Southeast Asian & Pacific Studies (CSEAPS) Public Expenditures in India and its impact on the Deficits 67 Jasneet Kaur Wadhwa Educational Status of India and China: A Silver Line for 93 © 2013 Centre for Southeast Asian & Pacific Studies Development ISSN 0975 - 6035 (Print) Shamshad & Md. Naiyer Zaidy Area Studies: A Journal of International Studies and Analyses Palestinian Politics and the Arab Spring: Some Critical Issues 118 Santhosh Mathew & Prasad M.V Reprint permission may be obtained from: The Editor The Behavior of Individual Investors in Transition Economies: 126 Email: [email protected] The Case of Kyrgyzstan Ebru Çağlayan & Raziiakhan Abdieva The responsibilities for facts and opinions presented in the articles rests exclusively with the individual authors. Their interpretations do not The Economic Impact of Agricultural And Clothing, Textile: 144 necessarily reflect the view or the policy of the Editorial Committee, An Input- Output Analysis National and International Advisory boards of Area Studies: A Journal of International Studies and Analyses. Nguyen Van Chung Layout & Printed at: D&Dee - Designing and Creative Production, Nallakunta, Hyderabad - 500 044. Ph No: +91 9440 726 907, 040 - 2764 3862. -

Flamin' Hot Founder Speaks at Goodwin Lecture Series

Student-run newspaper since 1962 TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2020 WWW.NEIUINDEPENDENT.ORG VOLUME 39 ISSUE 12 Flamin’ Hot founder speaks PAGE 3 NEWS at Goodwin Lecture Series NEIU social media accused of racist Valentine’s Day post PAGE 6 OPINIONS Minority should vote blue. Here’s why. PAGE 11 ARTS & LIFE Billboard-topping Theory (fmr. of a Deadman) talk new album PAGE 18 PAGE 5 SPORTS Part Two: Greatest matches in Wrestlemania history 2 NEWS | FEBRUARY 25, 2020 NEIUINDEPENDENT.ORG INDEPENDENT Student Veterans Club IN THIS ISSUE: reinvigorated with new leadership Can’s goal as president of the of Veteran Affairs and the Nation- sues, many veterans are left behind. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Earnest Beeson SVC is to encourage our university’s al Institute of Health, many suffer While their skills may put them at Matthew Rago Writer veterans to assume an active role in from homelessness, PTSD, suicidal an advantage, the disadvantage of “We’re not what you see in the the future of the university. He also ideations and divorce, often at the not being able to translate those movies,” the newly-elected 23-year- urges veterans and nonveterans same time. skills outweigh any benefit. SECTION EDITORS old president of the Student Veter- alike to support the SVC by joining Can and his team have big As of Jan. 2020, the Department Rachel Willard ans Club (SVC), Gabriel Can, says their ranks. The only requirement plans for the SVC. They have al- of Labor reported veteran unem- Montgomery Blair about veterans. Just last semester, for joining the SVC, he points out, ready begun by increasing mem- ployment at 3.1%.