Understanding Change in the Lives of Dalits of East Punjab Since 1947*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sn Village Name Hadbast No. Patvar Area Kanungo Area 1991 2001

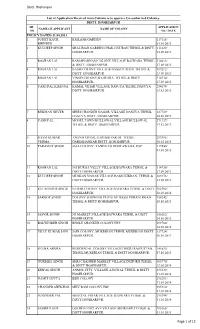

DISTT. HOSHIAR PUR KANDI/SUB-MOUNTAIN AREA POPULATION POPULATION SN VILLAGE NAME HADBAST NO. PATVAR AREA KANUNGO AREA 1991 2001 12 3 4 5 6 7 Block Hoshiarpur-I 1 ADAMWAL 370 ADAMWAL HOSHIARPUR 2659 3053 2 AJOWAL 371 ADAMWAL HOSHIARPUR 1833 2768 3 SAINCHAN 377 BHAGOWAL HOSHIARPUR 600 729 4 SARAIN 378 BHAGOWAL HOSHIARPUR 228 320 5 SATIAL 366 BASSI KIKRAN JAHAN KHELAN 328 429 6 SHERPUR BAHTIAN 367 CHOHAL HOSHIARPUR 639 776 7 KAKON 375 KAKON HOSHIARPUR 1301 1333 8 KOTLA GONSPUR 369 KOTLA GAUNS PUR HOSHIARPUR 522 955 9 KOTLA MARUF JHARI 361 BAHADAR PUR HOSHIARPUR 131 7 10 KANTIAN 392 KANTIAN HOSHIARPUR 741 1059 11 KHOKHLI 383 BHAGOWAL HOSHIARPUR 162 146 12 KHUNDA 395 BHEKHOWAL HOSHIARPUR 138 195 13 CHAK SWANA 394 KANTIAN HOSHIARPUR 121 171 KANDI-HPR.xls Hoshiarpur 1 DISTT. HOSHIAR PUR KANDI/SUB-MOUNTAIN AREA POPULATION POPULATION SN VILLAGE NAME HADBAST NO. PATVAR AREA KANUNGO AREA 1991 2001 14 THATHAL 368 KOTLA GAUNS PUR HOSHIARPUR 488 584 15 NUR TALAI 393 BHEKHOWAL HOSHIARPUR 221 286 16 BAGPUR 382 BAG PUR HOSHIARPUR 1228 1230 17 BANSARKAR URF NAND 364 BASSI GULAM HUSSA JAHAN KHELAN 632 654 18 BASSI GULAM HUSSAIN 362 BASSI GULAM HUSSAIN JAHAN KHELAN 2595 2744 19 BASSI KHIZAR KHAN 372 NALOIAN HOSHIARPUR 71 120 20 BASSI KIKRAN 365 BASSI KIKRAN JAHAN KHELAN 831 1096 21 BASSI MARUF HUSSAI 380 KANTIAN HOSHIARPUR 1094 1475 22 BASSI-MARUF SIALA 381 BHEKHOWAL HOSHIARPUR 847 1052 23 BASSI PURANI 363 BASSI GULAM HUSSA JAHAN KHELAN 717 762 24 BASSI KASO 384 KANTIAN HOSHIARPUR 238 410 25 BHAGOWAL JATTAN 379 BHAGOWAL HOSHIARPUR 418 603 26 BHIKHOWAL 391 BHEKHOWAL HOSHIARPUR 1293 1660 27 KOTLA NAUDH SINGH 143 KOTLA NODH SINGH BULLOWAL 611 561 28 BASSI BALLO 376 KAKON HOSHIARPUR 53 57 KANDI-HPR.xls Hoshiarpur 2 DISTT. -

(OH) Category 1 30 Ranjit Kaur D/O V.P.O

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Beldar, Mali, Mali-cum-Chowkidar, Mali -cum-Beldar-cum- Chowkidar and Road Gang Beldar reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre ofMunicipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, OH No. No. and Father’s Name etc. %age of Sarv Shri/ Smt./ Miss disability 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 30 Ranjit Kaur D/o V.P.O. Depur, Hoshiarpur 15.02.1983 OH 60% Swarn Singh 2 32 Rohit Kumar S/o Vill. Bhavnal, PO Sahiana, 27.05.1982 OH 60% Gian Chand Teh. Mukerian, Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 3 93 Nitish Sharma S/o Vill. Talwara, Distt. 22.05.1989 OH 50% Jeewan Kumar Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 4 100 Sukhwinder Singh V.P.O. Amroh, Teh. 31.03.1999 OH 70% S/o Gurmit Singh Mukerian, Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 5 126 Charanjeet Singh S/o V.P.O. Lamin, Teh. Dasuya, 13.11.1995 OH 50% Ram Lal Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 6 152 Ravinder Kumar S/o Vill. Allo Bhatti, P.O. Kotli 05.03.1979 OH 40% Gian Chand Khass, Teh. Mukerian, Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 7 162 Narinder Singh S/o Vill. Jia Sahota Khurd. P.O. 13.09.1983 OH 60% Santokh Singh Gardhiwala, Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 8 177 Bhupinder Puri S/o V.P.O. Nainwan, Teh. 09.05.1986 OH 40% Somnath Garhshankar, Distt. Hoshiarpur, Punjab. 9 191 Sohan Lal S/o Nasib Vill. -

Autobiography As a Social Critique: a Study of Madhopuri's Changiya Rukh and Valmiki's Joothan

AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS A SOCIAL CRITIQUE: A STUDY OF MADHOPURI’S CHANGIYA RUKH AND VALMIKI’S JOOTHAN A Dissertation submitted to the Central University of Punjab For the Award of Master of Philosophy in Comparative Literature BY Kamaljeet kaur Administrative Guide: Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana Dissertation Coordinator: Dr. Amandeep Singh Centre for Comparative Literature School of Languages, Literature and Culture Central University of Punjab, Bathinda March, 2012 CERTIFICATE I declare that the dissertation entitled ‘‘AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS A SOCIAL CRITIQUE: A STUDY OF MADHOPURI’S CHANGIYA RUKH AND VALMIKI’S JOOTHAN’’ has been prepared by me under the guidance of Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana, Administrative Guide, Acting Dean, School of Languages, Literature and Culture and Dr. Amandeep Singh, Assistant Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature, Central University of Punjab. No part of this dissertation has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. (Kamaljeet Kaur) Centre for Comparative Literature School of Languages, Literature and Culture Central University of Punjab Bathinda-151001 Punjab, India Date: i CERTIFICATE I certify that KAMALJEET KAUR has prepared her dissertation entitled “AUTOBIOGRAPHY AS A SOCIAL CRITIQUE: A STUDY OF MADHOPURI’S CHANGIYA RUKH AND VALMIKI’S JOOTHAN”, for the award of M.Phil. degree of the Central University of Punjab, under my guidance. She has carried out this work at the Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab. (Dr. Amandeep Singh) Assistant Professor Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. Date: (Prof. Paramjit Singh Ramana) Acting Dean Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. -

SN Name of the District/Constituency/ Village Block Total Population As

LIST OF KANDI AREA VILLAGES SN Name of the District/Constituency/ Block Total population as Village per census 2001 1 2 3 4 District : Hoshiarpur Constituency - Hoshiarpur 1 Adamwal Hoshiarpur-1 3053 2 Ajowal Hoshiarpur-1 2768 3 Sainchan Hoshiarpur-1 729 4 Sarain Hoshiarpur-1 320 5 Satial Hoshiarpur-1 429 6 Sherpur Bahtian Hoshiarpur-1 776 7 Kotla Gaunspur Hoshiarpur-1 955 8 Kotla Maruf Jhari Hoshiarpur-1 7 9 Bassi Gulam Hussain Hoshiarpur-1 2744 10 Bassi Kikran Hoshiarpur-1 1096 11 Bassi Purani Hoshiarpur-1 762 12 Thathal Hoshiarpur-1 584 13 Amowal Hoshiarpur-1 0 14 Saleran Hoshiarpur-1 1085 15 Shamaspur Hoshiarpur-1 17 16 Singhpur Hoshiarpur-1 374 17 Shergarh Hoshiarpur-1 2456 18 Qila Berun Hoshiarpur-1 1213 19 Kharkan Hoshiarpur-2 2452 20 Chak Harnoli Hoshiarpur-2 829 21 Chohal Hoshiarpur-2 7433 22 Chhauni Kalan Hoshiarpur-2 2373 23 Jahan Khelan Hoshiarpur-2 2394 24 Dada Hoshiarpur-2 1799 25 Dalewal Hoshiarpur-2 631 26 Tharoli Hoshiarpur-2 479 27 Dhirowal Hoshiarpur-2 214 28 Nasran Hoshiarpur-2 180 29 Naru Nangla Pind Hoshiarpur-2 465 30 Naru Nangal Khas Hoshiarpur-2 2160 31 Nara Hoshiarpur-2 1014 32 Nari Hoshiarpur-2 417 33 Nangal Shahidan Hoshiarpur-2 1432 34 Patiari Hoshiarpur-2 429 35 Bahaderpur Bahian Hoshiarpur-2 700 36 Bajwara Hoshiarpur-2 7516 37 Bilaspur Hoshiarpur-2 925 38 Bassi Ali Khan Hoshiarpur-2 460 39 Bassi Daud Khan Hoshiarpur-2 339 40 Bassi Alladin Hoshiarpur-2 56 41 Barkian Tanuran Hoshiarpur-2 0 42 Bassi Bahian Hoshiarpur-2 156 43 Bassi Hashmat Khan Hoshiarpur-2 696 44 Bassi Mustfa Hoshiarpur-2 655 45 Bassi Jaura Hoshiarpur-2 386 46 Bassi Jamal Khan Hoshiarpur-2 196 47 Bassi Shah Mohamad Hoshiarpur-2 67 48 Mochpur Hoshiarpur-2 212 49 Manan Hoshiarpur-2 1148 50 Manjhi Hoshiarpur-2 1154 51 Mehlanwali Hoshiarpur-2 3115 52 Mehatpur Hoshiarpur-2 902 Total : (Constitutency - Hoshiarpur) 62752 Constituency - Shamchurasi 1 Ikhilaspur Hoshiarpur-1 294 2 Kakon Hoshiarpur-1 1333 3 Khokhli Hoshiarpur-1 146 10. -

Complete PNRC 21 to 34305 for EXPORT TO

S.NO. CANDIDATE NAME FATHER'S NAME QUALIFICATION ADDRESS DATE OF PNRC MIDWIFE OLD REM ANM REGN Regno Regno Regno ARK Regno 14322 Jasprit Kaur Karnail Singh Nurse & Midwife V.P.O. DHARAMKOT(FROZPUR) 27.01.1998 14268 15355 14323 Sarabjit Kaur Karnail Singh Nurse & Midwife H NO 11096, STREET NO.0, NEW SUBHASH 27.01.1998 14269 15356 NAGAR, LUDHIANA 14324 Harjit Kaur Malkit Singh Nurse & Midwife V.P.O. LARIYA VIA 27.01.1998 14270 15357 BHOGPUR(JALLANDHAR) 14325 Manjit Kaur Jaswinderq Nurse & Midwife V. CHIRAN WALI (MUKTSAR) 27.01.1998 14271 15358 14326 Preetmohinder Kaur Sursewak Singh Nurse & Midwife H NO 3202, RAJPURA TOWN, DISTT 27.01.1998 14272 15359 PATIALA 14327 Santosh Kaur Gurmukh Singh Nurse & Midwife V. MANGAL BHAWAN, P.O QADIAN 27.01.1998 14273 15360 (GURDASPUR) 14328 Mamta Rani Somnath Nurse & Midwife D-636 A/1 ASHOK NAGAR, NEAR SHITLA 27.01.1998 14274 15361 MATA MANDIR. DELHI 14329 Neeraj Kumari Shyamnarayan Rai Nurse & Midwife C-4/221, YAMUNA VIHAR DELHI 27.01.1998 14275 15362 14330 Ranjana Kumari Ram Kishor Nurse & Midwife F-5/7172, SULTANPUR, DELHI 27.01.1998 14276 15363 14331 Minakshi Manohar Lal Nurse & Midwife V.LEHAL DHARIWAL (GURDASPUR) 27.01.1998 14277 15364 14332 Paramjit Kaur Kamal Raj Nurse & Midwife H NO 73, MOHALLA RAVIDASS PURA, 27.01.1998 14278 15365 SAMRALLA CHOWK BYE PASS. LUDHIANA 14333 Seema Passi Joginder Ram Nurse & Midwife H NO 99, RAJA GARDEN COLONY 27.01.1998 14279 15366 JALLANDHAR 14334 Jagroop Kaur Lakha Singh Nurse & Midwife V.KARIONWAL (AMRITSAR) 28.01.1998 14280 15367 14335 Jaswinder Kaur Atma Singh Nurse & Midwife V.MALLAH, P.O KANG(AMRITSAR) 28.01.1998 14281 15368 14336 Harmeet Kaur Swarn Singh Nurse & Midwife V.P.O. -

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administrative Detail of Repair Approval Sr

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administrative Detail of Repair Approval Sr. Name of Name Xen/Mobile No. Distt. MC Name of Work Strengthe Premix No. Length Cost Raising Contractor/Agency Name of SDO/Mobile No. ning Carepet in in Km. in lacs in Km in Km Km 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 1 Hoshiarpur Mukerian NHIA to Dasuya Hajipur Road 16.96 186.44 3.03 5.11 16.96 Co. [Gr.No.1] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 2 Hoshiarpur Mukerian Mukerian to Dasuya Hajipur road 10.65 130.85 1.68 2.35 10.65 Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 Mukerian Hajipur road to Dallowal & link M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 3 Hoshiarpur Mukerian 0.5 6.33 0.04 0.38 0.5 to Phirni of vill. Dallowal Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 4 Hoshiarpur Mukerian Mukerian Hajipur road to Ralli 1.42 16.87 0.44 0.17 1.42 Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 5 Hoshiarpur Mukerian Mukerian Hajipur road to Jahidpur 0.5 5.98 -- 0.3 0.5 Co. [Gr.No.2] Er.Davinder Kumar / 9478734720 Mukerian Hajipur road to Dallowal & link M/s Parduman Singh & Er.Pawan Kumar / 9780000084 6 Hoshiarpur Mukerian 1.2 16.34 0.2 0.81 1.2 to Phirni of vill. -

Distt. Hoshiarpur Page 1 of 12

Distt. Hoshiarpur List of Application Received from Colonizers to approve Un-authorized Colonies. DISTT. HOSHIARPUR SR. APPLICATION NAME OF APPLICANT NAME OF COLONY NO NO./ DATE POLICY DATED 21.08.2013 1 SURJIT KAUR KAILASH GARDEN 119118/ BHINDER 01.10.2013 2 KULDEEP SINGH SHALIMAR GARDEN,CHAK GUJJRAN TEHSIL & DISTT. 111629/ HOSHIARPUR. 25.09.2013 3 ROSHAN LAL RAM SHARNAM COLONY,VILLAGE BAJWARA TEHSIL 114616/ & DISTT. HOSHIARPUR. 27.09.2013 4 ROSHAN LAL BASSI COLONY VILLAGE BASSI PURANI TEHSIL & 109212/ DISTT. HOSHIARPUR. 23.09.2013 5 ROSHAN LAL VINOD COLONY,BAJWARA TEHSIL & DISTT. 114730/ HOSHIARPUR. 27.09.2013 6 YASH PAL KHANNA KAMAL VIHAR VILLAGE DASUYA TEHSIL DASUYA 284674/ DISTT. HOSHAIRPUR. 13.12.2013 7 RUKMAN NEVER SHIRI CHANDER NAGAR ,VILLAGE DASUYA TEHSIL 127729/ DASUYA DISTT. HOSHIARPUR. 04.10.2013 8 YASH PAL MODEL TOWN BULLOWAL VILLAGE BULLOWAL 271337/ TEHSIL & DISTT. HOSHIARPUR. 17.12.2013 9 SHAM KUMAR ANAND VIHAR, GARHSHANKAR TEHSIL 293996/ VERMA GARHSHANKAR DISTT. HOSHIARPUR. 30.01.2014 10 PARAMJIT SINGH JAJA COLONY, TANDA TO DHOLAWAHA, HSP 119540/ 01.10.2013 11 ROSHAN LAL JAI DURGA VELLY VILLAGE,BAJWARA TEHSIL & 114750/ DISTT HOSHIARPUR. 27.09.2013 12 KULDEEP SINGH MUSKAN NAGAR VILLAGE BASSI KIKRAN, TEHSIL & 109176/ DISTT HOSHIARPUR. 23.09.2013 13 KULWINDER SINGH NEHAR COLONY VILLAGE BAJWARA TEHSIL & DISTT 302302/ HOSHIARPUR. 10.03.2014 14 SAROOP SINGH COLONY SHOWING PLOTS AT BASSI PURANI ROAD 154242/ TEHSIL & DISTT HOSHIARPUR. 10.10.2013 15 JASVIR SINGH J.P.MARKET,VILLAGE BAJWARA TEHSIL & DISTT 186662/ HOSHIARPUR. 24.10.2013 16 BALWINDER SINGH BHOLE SHANKER COLONY HSP 299700/ 24.02.2014 17 VIJAY KUMAR JAIN JAIN COLONY, MUKERIAN,TEHSIL MUKERIAN DISTT. -

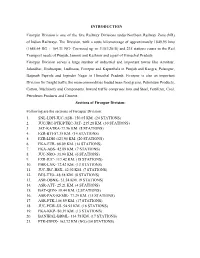

Of Indian Railways. The

INTRODUCTION Firozpur Division is one of the five Railway Divisions under Northern Railway Zone (NR) of Indian Railways. The Division, with a route kilometerage of approximately 1849.95 kms (1685.64 BG + 164.31 NG- Corrected up to 31/03/2018) and 235 stations caters to the Rail Transport needs of Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir and a part of Himachal Pradesh. Firozpur Division serves a large number of industrial and important towns like Amritsar, Jalandhar, Hoshiarpur, Ludhiana, Firozpur and Kapurthala in Punjab and Kangra, Palampur, Baijnath Paprola and Joginder Nagar in Himachal Pradesh. Firozpur is also an important Division for freight traffic the main commodities loaded been food grains, Petroleum Products, Cotton, Machinery and Components. Inward traffic comprises Iron and Steel, Fertilizer, Coal, Petroleum Products and Cement. Sections of Firozpur Division: Following are the sections of Firozpur Division: 1. SNL-LDH-JUC-ASR- 150.65 KM. (24 STATIONS) 2. JUC/JRC-PTK/PTKC-JAT- 215.28 KM. (30 STATIONS) 3. JAT-KATRA-77.96 KM. (8 STATIONS) 4. FZR-BTI-87.35 KM. (14 STATIONS) 5. FZR-LDH -123.95 KM. (20 STATIONS) 6. FKA-FZR- 88.09 KM. (14 STATIONS) 7. FKA-ABS- 42.89 KM. (7 STATIONS) 8. JUC-NRO- 31.90 KM. (6 STATIONS) 9. FZR-JUC- 117.42 KM. (18 STATIONS) 10. PHR-LNK- 72.42 KM. (13 STATIONS) 11. JUC-JRC-HSX- 42.92 KM. (7 STATIONS) 12. BES-TTO- 48.58 KM. (8 STATIONS) 13. ASR-DBNK- 53.54 KM. (9 STATIONS) 14. ASR-ATT- 25.21 KM. (4 STATIONS) 15. BAT-QDN- 19.44 KM. -

![Download Entire Journal Volume No. 2 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8223/download-entire-journal-volume-no-2-pdf-1858223.webp)

Download Entire Journal Volume No. 2 [PDF]

JOURNAL OF PUNJAB STUDIES Editors Indu Banga Panjab University, Chandigarh, INDIA Mark Juergensmeyer University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Gurinder Singh Mann University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Ian Talbot Southampton University, UK Shinder Singh Thandi Coventry University, UK Book Review Editor Eleanor Nesbitt University of Warwick, UK Editorial Advisors Ishtiaq Ahmed Stockholm University, SWEDEN Tony Ballantyne University of Otago, NEW ZEALAND Parminder Bhachu Clark University, USA Harvinder Singh Bhatti Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Anna B. Bigelow North Carolina State University, USA Richard M. Eaton University of Arizona, Tucson, USA Ainslie T. Embree Columbia University, USA Louis E. Fenech University of Northern Iowa, USA Rahuldeep Singh Gill California Lutheran University, Thousand Oaks, USA Sucha Singh Gill Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Tejwant Singh Gill Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, INDIA David Gilmartin North Carolina State University, USA William J. Glover University of Michigan, USA J.S. Grewal Institute of Punjab Studies, Chandigarh, INDIA John S. Hawley Barnard College, Columbia University, USA Gurpreet Singh Lehal Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Iftikhar Malik Bath Spa University, UK Scott Marcus University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Daniel M. Michon Claremont McKenna College, CA, USA Farina Mir University of Michigan, USA Anne Murphy University of British Columbia, CANADA Kristina Myrvold Lund University, SWEDEN Rana Nayar Panjab University, Chandigarh, INDIA Harjot Oberoi University -

Mukerian Assembly Punjab Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781-84 Email : [email protected] Website : www.indiastatelections.com Online Book Store : www.indiastatpublications.com Report No. : AFB/PB-039-0121 ISBN : 978-93-5301-551-0 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : January, 2021 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 245 for the use of this publication. Printed in India Contents No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency - (Vidhan Sabha) at a Glance | Features of Assembly 1-2 as per Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency - (Vidhan Sabha) in 2 District | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary 3-10 Constituency - (Lok Sabha) | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2017, 2014, 2012 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 11-23 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographic 4 Population Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and -

Dalit Literature in Punjabi

SPECIAL ARTICLE Existence, Identity and Beyond Tracing the Contours of Dalit Literature in Punjabi Paramjit S Judge This paper traces the development and emergence of he expression “dalit literature” invariably invokes an Punjabi dalit literature as a part of dalit assertion and ambivalent response for two reasons. One, it is not a genre of literature, but a type of literature based on the effervescence in postcolonial India. Today, Punjabi dalit T social background of the creative writers and subsumes the literature is well established despite its very short history. existence of all genres of literature. Therefore, we have French The two significant features of dalit literature – powerful literature, black literature, ethnic literature, African literature, narratives constructed about the existential conditions immigrant literature, Indian literature and so on. Such a typo- logy may sometimes exist for the sole purpose of pure classifi - of the dalits and an overarching emphasis on dalit cation of the various courses in academic institutions. How- identity – are examined, so too Punjabi dalit literature in ever, the classifi cation may serve a heuristic purpose, as in the terms of the agenda of dalit liberation that is articulated case of the periodic table which classifi es the various chemical in various genres. elements. In such a situation, the various genres of literature are combined to create a “type” on the basis of certain charac- teristics. Thus romantic literature has certain characteristics; so is the case with dalit literature. However, like ethnic litera- ture, dalit literature is the creation of writers who could be categorised as dalits. It is not necessary that a writer’s work be classifi ed as dalit simply on the basis of the fact that he/she is a dalit. -

Name , Email Id & Contact Number of PIO in Distt. Hoshiarpur

Name , email id & contact number of PIO in Distt. Hoshiarpur. S. Office Name of PIO & First ASDA/APIO email ID No Appelate Authority 1 D.C Office DRO, Hoshiarpur [email protected] Hoshiarpur (Sh. Amanpal 98148-53692 Singh)(PIO) Smt.Asha Rani ( supdt G-1) 9876392293 Sh. Balkar Singh (Supdtt.-II) (APIO) 98761- 22281 [email protected] Sh. Amit Kumar 01882-220306 Panchal(ADC(G)) (First Appelate Authority ) 2 SDM, office Mrs.Gurjinder Kaur Mrs.Gurmail Kaur [email protected] Hoshiarpur ( Supdt G-2)(PIO) 99154-06432(APIO) 89684-52122 Sh. Amit Mahajan (SDM, Hoshiarpur) (First Appelate Authority ) [email protected] 01882-220310 3 Tehsil office Sh.Harminder Singh Sh.Gurpreeet Singh [email protected] Hoshiarpur (Tehsildar) ( N.T. Hosiarpur)(APIO) 98149-00051 98142-00020 (PIO) Sh. Amit Mahajan (SDM, Hoshiarpur) [email protected] (First Appelate Authority ) 01882-220310 4 SDM, office Sh.Sanjeev Kumar Dasuya 98786-70183(PIO) Sh.Gulshan Singh [email protected] (APIO) Sh. Randeep Singh Heer (9417453550) SDM Dasuya(First Appelate Authority ) [email protected] (01883-285022) 5 Tehsildar Sh.Kirandeep Bhullar office 98151-00016(PIO) Sh. Sukhwinder [email protected] Dasuya Singh(NT Sh. Randeep Singh Heer Dasuya)(APIO) SDM, Dasuya(First Appelate Authority ) [email protected] (918558980692) (01883-285022) 6 SDM, office Sh.Saroop Lal, (PIO) ------ [email protected] Mukerian 94177-65893 Sh. Ashok Kumar SDM Mukerian (First Appelate [email protected] Authority)01883- 244441 7 Tehsildar Sh. Jagtar Singh Sh.Avinash Chander [email protected] office (Tehsildar )(PIO) (N.T.Mukerian)(API Mukerian O) 97802-00015 Sh.