Dependence on the Whale Author Version Text Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Who Party

The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Tim Harrison, Sr. as the 4th Doctor and Eric Stein as Captain Jack Harkness Jim Martin as the 9th Doctor Sarah Gilbertson as Raffalo (The End of the World) Esther Harrison as Harriet Jones (The Christmas Invasion) Karen Martin as Rose Tyler Jesse Stein as the 10th Doctor Katie Grzebin as Novice Hame (New Earth) Timothy Harrison, Jr. as the 10th Doctor and Lindsay Harrison as Rose Tyler (Tooth and Claw) JoLynn Graubart as Martha Jones and Matt Graubart as a Weeping Angel (Blink) Andrew Gilbertson as Prof. Yana (Utopia) Kayleigh Bickings as Lady Christina (Planet of the Dead) Joe Harrison as a Whifferdill (taking the form of Joe Harrison) (DWM: Voyager) 4, 9, 10, and everyone’s favorite Canine Computer... A bowl of Adipose... No substitute for a sonic blaster, but the 9th and 10th are fans... HOME 2010 The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Andrew Gilbertson as the 1st Doctor Hayley as a Dalek Camryn Bickings as ...Koquillion? (The Rescue) Timothy Harrison, Jr. as the 5th Doctor Jim Martin as the 9th Doctor Esther Harrison as Sarah Jane Smith BJ Johnson as a Weeping Angel (Blink) Sarah Gilbertson as Lucy Saxon (Last of the Time Lords) Katie Grzebin as Jenny (The Doctor’s Daughter) Karen Martin as the Visionary (The End of Time) Eric Stein as the post-regeneration 11th Doctor (The Eleventh Hour) Joe Harrison as the 11th Doctor Lindsay Harrison as Liz 10 (The Beast Below) JoLynn Graubart as Amy Pond and Matt Graubart as Rory the Roman (The Pandorica Opens) HOME 2009 2011 The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Andrew Gilbertson as the 2nd Doctor Joe Harrison as Jamie McCrimmon Timothy Harrison, Jr. -

Doctor Who and the Creation of a Non-Gendered Hero Archetype

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 10-13-2014 Doctor Who and the Creation of a Non-Gendered Hero Archetype Alessandra J. Pelusi Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Pelusi, Alessandra J., "Doctor Who and the Creation of a Non-Gendered Hero Archetype" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 272. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/272 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOCTOR WHO AND THE CREATION OF A NON-GENDERED HERO ARCHETYPE Alessandra J. Pelusi 85 Pages December 2014 This thesis investigates the ways in which the television program Doctor Who forges a new, non-gendered, hero archetype from the amalgamation of its main characters. In order to demonstrate how this is achieved, I begin with reviewing some of the significant and relevant characters that contribute to this. I then examine the ways in which female and male characters are represented in Doctor Who, including who they are, their relationship with the Doctor, and what major narrative roles they play. I follow this with a discussion of the significance of the companion, including their status as equal to the Doctor. From there, I explore the ways in which the program utilizes existing archetypes by subverting them and disrupting the status quo. -

Doctor Who and the Politics of Casting Lorna Jowett, University

Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett, University of Northampton Abstract: This article argues that while long-running science fiction series Doctor Who (1963-89; 1996; 2005-) has started to address a lack of diversity in its casting, there are still significant imbalances. Characters appearing in single episodes are more likely to be colourblind cast than recurring and major characters, particularly the title character. This is problematic for the BBC as a public service broadcaster but is also indicative of larger inequalities in the television industry. Examining various examples of actors cast in Doctor Who, including Pearl Mackie who plays companion Bill Potts, the article argues that while steady progress is being made – in the series and in the industry – colourblind casting often comes into tension with commercial interests and more risk-averse decision-making. Keywords: colourblind casting, television industry, actors, inequality, diversity, race, LGBTQ+ 1 Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett The Britain I come from is the most successful, diverse, multicultural country on earth. But here’s my point: you wouldn’t know it if you turned on the TV. Too many of our creative decision-makers share the same background. They decide which stories get told, and those stories decide how Britain is viewed. (Idris Elba 2016) If anyone watches Bill and she makes them feel that there is more of a place for them then that’s fantastic. I remember not seeing people that looked like me on TV when I was little. My mum would shout: ‘Pearl! Come and see. -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

Post-Feminist Retreatism in Doctor Who Franke, A

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch 'Don't make me go back': post-feminist retreatism in Doctor Who Franke, A. and Nicol, D. This is an author accepted manuscript of an article published by Intellect in the Journal of Popular Television, 6 (2), pp. 197-211. The final definitive version is available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.1386/jptv.6.2.197_1 © 2018 Intellect The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] ‘Don’t Make Me Go Back’: Post-Feminist Retreatism in Doctor Who By Alyssa Franke and Danny Nicol ABSTRACT In post-2005 Doctor Who the female companion has become a seminal figure. This article shows how closely the narratives of the companions track contemporary notions of post- feminism. In particular, companions’ departures from the programme have much in common with post-feminism’s master-theme of retreatism, whereby women retreat from their public lives to find fulfilment in marriage, home and family. The article argues that when companions leave the TARDIS, what happens next ought to embody the sense of empowerment, purpose and agency which they have gained through their adventures, whereas too often the programme’s authors have given companions ‘happy endings’ based on finding husbands and settling down. -

THE CLASSIC DOCTOR WHO DVD COMPENDIUM Page Addition to First Printing

THE CLASSIC DOCTOR WHO DVD COMPENDIUM page addition to first printing Print both pages of this PDF on either side of an A4 sheet, using the corner markers to check they are aligned. If your printer cannot do this, print each page separately. Trim the page(s) in line with the markers, or slightly inside them to prevent the insert sticking out from the edges of the book, particularly on the spine edge (dotted line). Place the trimmed page between pages 330 and 331 of your book. THE UNDERWATER MENACE STORY NO.32 SEASON NO.4:5 One disc with two original and two reconstructed episodes (97½ mins) and 63 minutes of extras, plus commentary track Audio navigation of disc contents available by pressing Enter after the BBC ident TARDIS TEAM Second Doctor, Ben, Jamie, Polly TIME AND PLACE Contemporary Atlantis, near the Azores ADVERSARIES Atlanteans; Professor Zaroff FIRST ON TV 14 January–4 February 1967 DVD RELEASE BBCDVD3691, 26 October 2015, PG COVER Photo illustration by Lee Binding, blue strip; version with older BBC logo on reverse ORIGINAL RRP £20.42 — Episode three originally released in the Lost in Time set; BBCDVD1353, £29.99, 1 November 2004 STORY TEASER TheTARDIS arrives on a small volcanic island in the Atlantic Ocean yet there are signs of habitation. Indeed, the travellers are soon captured and taken deep below the surface where a small community of people worship their fish-god Amdo — and are only too happy to have fresh sacrifices to offer her. Also down here is the brilliant scientist Professor Zaroff; brilliant but totally mad. -

IDENTITY FALL 2018 EDITION Table of Contents

TIMBER CREEK ART AND LITERATURE MAGAZINE IDENTITY FALL 2018 EDITION Table of Contents IDENTITY Heart and Soul - Tianna Kell Palacios Irizarry Autopilot - Clementine Untitled - Joanna Timber Creek’s Fall 2018 Art and Surge - Clementine Unwritten - Brandan Riley Literature Magazine American Heroes - Gabriela The Acountant - Michelle Santiago Fulkerson The Monster - Clementines This is America - Michelle Labels - Katiejo Fairchild Fulkerson Every person has their own unique identity. Different per- Not Exactly Built by Books - Whispers - Aydin Bojkovic Anonymous Buspirone - Jessica Parks sonality traits define us, our life experiences define us, we I Darken - Megan Goin With Great Power - Taimani define us. The goal of the Art & Literature Magazine is to Cnadle Light - Brandan Riley Matthew share Timber Creek’s various identites through creative I Hate the Color Red - Erik Heiss Untitled - David Petroff art and writing. We hope to shine a light on any of those Caged - Caitlyn Metcalf Lady in White - Kat McDonald who may be hiding in the shadows or wearing a mask to Light and Dark - Angel Maher Wilson Heaven of Hell - Brendan Barnett Lovable Failure - Jay cover up who they truly are. These stories will hopefully Untitled - Samantha Bajonero Tempestuous Green - Roan reveal that no one should have to hide - that every identity Anxiety - Jselyn Lane Who I Am - Aimee Zuniga is beautiful in its own glorious way. The Girl With the Frozen Eye - The Glass - Samuel Monthie Meighan Ashford Gnarled Hands - Joshua Her - Arden Williams Sedimentary Layers - Tabitha The Lit Mag Team would like to thank every student who Life’s Facade - Megan Polanco Tomlinson Vacation Today - AKA Saint Peter - Michelle Fulkerson submitted their incredible creative projects. -

Doctor Who, New Dimensions and the Inner World: a Reciprocal Review

84 Media Education Research Journal Doctor Who, New Dimensions and the Inner World: A Reciprocal Review Two significant additions to Doctor Who’s academic ‘canon’ were published recently and, continuing our interest in new ways of approaching the review format, here we ask two authors, Iain MacRury and Matt Hills, to appraise each others’ texts. Iain MacRury, I. and Rustin, M. (2013) The Inner World of Doctor Who London: Karnac Books. This book, part of the ‘Psychoanalysis and Popular Culture’ series, does two things that are relatively unusual within the dimensions of Doctor Who scholarship. Firstly, it relates psychoanalytic thinking to the programme, and secondly it focuses on a selected range of texts, which, though they all hail from the BBC Wales’ version of the show, are not otherwise structured by production eras. Instead, case study texts are chosen on the basis of the authors’ emotional and mindful responses to them. MacRury and Rustin deliberately set out to neglect many things that have preoccupied recent media/cultural studies, e.g. the productivity of fan audiences or the proliferation of transmedia and promotional paratexts. Perhaps these might constitute the ‘outer worlds’ of Doctor Who, markers of its industrial and cultural contexts. By contrast, this book seeks to return to traditional modes of textual study. It’s a decision that leads to some characteristic strengths and occasional weaknesses. On the plus side, there are many smart observations here which provoke new ways of seeing ‘nu Who’. The Daleks, for example, have been thought about previously as symbolic of Nazism, as representing rage-filled children’s tantrums, or even as resembling BBC cameras from the 1960s. -

The Wall of Lies

The Wall of Lies Number 149 Newsletter established 1991, club formed June first 1980 The newsletter of the South Australian Doctor Who Fan Club Inc., also known as SFSA Final STATE Adelaide, July--August 2014 WEATHER: Venus, pre-1957 Free Who’s not coming to Adelaide? by staff writers Time Lords have been messing with the dematerialisation circuit. On 11 June 2013 the BBC announced a worldwide tour of the current Doctor Who regulars Peter Capaldi and Jenna Coleman. Doctor Who: The World Tour will visit such far off locales as New York, Mexico City, Seoul, Sydney and Rio de Janeiro. High on the list of places they are not visiting is Adelaide. Steven Moffat, show runner who is accompanying part of the tour, is understood to have been a strong advocate for Metebelis III and Gallifrey. However compromises have been made, and visits O u N t to London and Cardiff are also planned. Doctor Who No ow Moffat; trapped in a rectangle, fans in the UK and also Great Britain are understood ! but quite well dressed. to be overjoyed at this unprecedented contact with the stars. ABC: It’s 24 August for Doctor Who! by staff writers ABC plays new Who as soon as possible. ABC announced the fast track of Doctor Who series eight on 29 June, only two days after the BBC confirmed the premiere date 50th Programme of 23 August on BBC One. This will follow the 2013 repeats in the schedule and be only fourteen hours after the UK premiere. O u ABC Managing Director Mark Scott told The Wall of Lies, ”I think S t So on we welcome a continuous series not a split one. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................................................5 Table of Contents ..............................................................................................................................7 Foreword by Gary Russell ............................................................................................................9 Preface ..................................................................................................................................................11 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................13 Chapter 1 The New World ............................................................................................................16 Chapter 2 Daleks Are (Almost) Everywhere ........................................................................25 Chapter 3 The Television Landscape is Changing ..............................................................38 Chapter 4 The Doctor Abroad .....................................................................................................45 Sidebar: The Importance of Earnest Videotape Trading .......................................49 Chapter 5 Nothing But Star Wars ..............................................................................................53 Chapter 6 King of the Airwaves .................................................................................................62 -

Released with Audio Only Anim

Updated – 7/26/15 Released Lost – Won’t be released unless found Unreleased A – Released with Audio only Anim – Released with Lost video replaced by Animation CD – Audio only released on CD (Doctor Who: The Lost TV Episodes: Collections) Release Scheduled The First Doctor – William Hartnell Season 1 001 – An Unearthly Child (1–4) 002 – The Daleks (1–7) 003 – The Edge of Destruction (1–2) 004 – Marco Polo (1–7) CD 005 – The Keys of Marinus (1–6) 006 – The Aztecs (1–4) 007 – The Sensorites (1–6) 008 – The Reign of Terror (1–3,4–5Anim,6) CD Season 2 009 – Planet of Giants (1–3) 010 – The Dalek Invasion of Earth (1–6) 011 – The Rescue (1–2) 012 – The Romans (1–4) 013 – The Web Planet (1–6) 014 – The Crusade (1,2A,3,4A) CD 015 – The Space Museum (1–4) 016 – The Chase (1–6) 017 – The Time Meddler (1–4) Season 3 018 – Galaxy 4 (1–2,3,4) CD 019 – Mission to the Unknown (1) 020 – The Myth Makers (1–4) CD 021 – The Daleks' Master Plan (1,2,3–4,5,6–9,10,11–12) CD 022 – The Massacre of St. Bartholomew's Eve (1–4) CD 023 – The Ark (1–4) 024 – The Celestial Toymaker (1–3,4) CD 025 – The Gunfighters (1–4) 026 – The Savages (1–4) CD 027 – The War Machines (1–4) Season 4 028 – The Smugglers (1–4) CD 029 – The Tenth Planet (1–3,4) CD The Second Doctor – Patrick Troughton 030 – The Power of the Daleks (1–6) CD 031 – The Highlanders (1–4) CD 032 – The Underwater Menace (1,2,3,4) CD 033 – The Moonbase (1A,2,3A,4) CD 034 – The Macra Terror (1–4) CD 035 – The Faceless Ones (1,2,3,4–6) CD 036 – The Evil of the Daleks (1,2,3–7) CD Season 5 037 – The Tomb of the -

Downloading Into Folders), and Audio, and Each Two-Disc Release Will Contain Eight Short Already the Sequel Is Well Underway

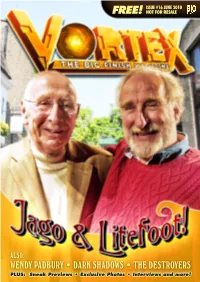

ISSUE #16 JUNE 2010 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE ALSO: WENDY PADBURY • DARK SHADOWS • THE DESTROYERS PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL One of the many joys of this job is that I get to do a lot Impressed by the poster, Callum scuttled off to Tracey of conventions. It’s a great opportunity to get out there, and pulled her over. “Look at this!” he enthused. “You meet the people who buy our CDs, and chat about the are part of the Doctor Who universe.” Tracey was stories and the ranges. And it’s a wonderful chance to indeed very happy, and burst into a broad grin. be reacquainted with our actors again, and just have a “Mind you, your picture’s really small compared to all bit of time to chat and catch up. We had a lot of fun at the others,” Callum added. the recent Utopia convention in Chipping Norton, where Tracey’s face collapsed into a feigned steely stare. people finally were able to see that Ken Bentley does She had that Klein look – the one that can destroy entire exist! Really, he does! And soon we’ll be at Bad Wolf timelines – and swivelled on her heels, marching away. in Birmingham – the Big Finish table will be staffed by Tracey and myself and Richard Dinnick, and Sarah Sutton and Lisa Callum – here’s Bowerman will be signing CDs. Nyssa and Benny at to you. I’m still the BF table! We hope to see many of you there... (for chortling now. details, see the ad on the inside back cover.) Mention of conventions brings me to a little tale David that makes me chortle.