A Philosophical and Literary Analysis, Lublin: Wyda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

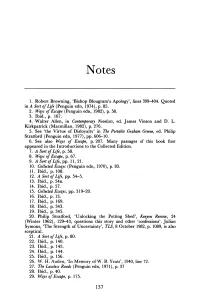

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Graham Greene's the Living Room: an Uncomfortable Catholic Play In

ATLANTIS Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies 40.1 (June 2018): 77-95 issn 0210-6124 | e-issn 1989-6840 doi: http://doi.org/10.28914/Atlantis-2018-40.1.04 Graham Greene’s The Living Room: An Uncomfortable Catholic Play in Franco’s Spain Mónica Olivares Leyva Universidad de Alcalá [email protected] This article addresses the debate over Graham Greene’s The Living Room (1953) in Franco’s Spain, where theatre critics created a controversy over the play by questioning whether this Catholic dramatic work was heretical or orthodox. It was regarded as a cultural asset to the national stage, but it was also interpreted as a threat to Catholics of wavering faith. In addition, this study uses the censorship files to examine the attitude of the Franco regime towards the play. Contrary to popular belief, Franco’s government did not favour the reception of this play despite the fact that Greene was an internationally renowned Catholic writer. On the contrary, banned four times, it ranks among Greene’s most censored works under Franco’s rule. The article concludes by suggesting that The Living Room became an uncomfortable Catholic play because it clashed with the tenets of the regime. Keywords: Graham Greene; Franco’s regime; theatre; criticism; censorship . El cuarto de estar, de Graham Greene: una obra católica incómoda en la España de Franco Este artículo pone de manifiesto el debate que tuvo lugar en la España de Franco en torno a El cuarto de estar (1953), de Graham Greene. Los críticos teatrales suscitaron una polémica a su alrededor al cuestionar si se trataba de una obra dramática católica de carácter herético u ortodoxo. -

And Graham Greene: a Comparati Vb Study

- THE RELIGIOUS CONCEPTS OF MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO AND GRAHAM GREENE: A COMPARATI VB STUDY A RESEARCH REPORT SUBMITfED TO THE HONORS COUNCIL IN PARTI AL FULF ILLMENT OF THE REqtJI REMENTS - FO R HONOR GRADUATION by SHA RON PRESTON AD VISER: MRS. HELEN GREENLEAF BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MA Y 1965 - - I 9 yt':; .PT/I ACI(No\'iLEDGMENT I wish to extend sincere acknowledgment to Mrs. Helen Greenleaf, professor of spanish language and literature here at Ball State University. Her keen interest and sensitive insight into people and ideas, particularly the Spanish, have kindled in me a deeper apTreciation of people and their thoughts, and, I hope, a greater flexibility in my own thinking. With out the stimulus of her storehouse of ideas and suggestions which have helped me so much, this paper would never have been -- written, nor in fact would the research ever have been begun. - TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i GOD AND HIS RELATIONSI-iIP TO MAN 1 LIFE AND IMMORTALITY 11 ROMAN CATHOLICISM 24 GO,)D A!\TD EVIL 36 SlJM!v'lARY AND CONCLUSION 51 BIBLIOGRAPHY 55 - INTRODUCTION Miguel de Ynamuno and Graham Sreene, a Spaniard and an Englishman, a non-Catholic and a Catholic, a man who continually questions and a man who has arrived at answers to his questions, are opposites in numerous ways. Yet there is a common ground on which they both stand, a basic factor which puts the two men on an even plane despite the differ- ences which exist between them.fhis factor is an intellec- tual and emotional inquiry into themselves and into the religious concepts which rresent themselves as possible solu- tions to the questions raised about human individuals. -

THE CATHOLIC TREATMENT OP SIN and REDEMPTION in the NOVELS of GRAHAM GREENE by Thomas M„ Sheehan

UNIVERSITY D'OTTAWA » ECOLE PES GRADUE5 .. / THE CATHOLIC TREATMENT OP SIN AND REDEMPTION IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE by Thomas M„ Sheehan Thesis presented to the English Department of the Graduate School of the faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy *****$*# *$> Ottawa, Canada and Louisville, Kentucky I960 UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA - SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: DC53535 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53535 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 UNIVERSITE D'OTTAWA - ECOLE DES GRADUES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis was prepared under the supervision of Dr. Emmett 0'Grady, Head of the English Department of the University of Ottawa. The writer is indebted t© Mr. P. B. Lysaght of London, England for invaluable material on Graham Greene that was not readily available either in the United States or in Canada. The writer is also indebted to the librar ians of Nazareth College, and Sellarmine College, Louisville, Kentucky for the use of their facilities. -

Het Tains Motif in Het Werk Van Graham Greene

Het Tains Motif in het werk van Graham Greene door R.A. Pierloot Samenvatting In de psychoanalytische traditie werden vader-zoonconflicten beschouwd als het gevolg van rivaliteit en doodswensen uitgaande van de zoon. Maar sinds enkele ja- ren werd de aandacht getrokken op het bestaan van agressieve impulsen bij de vader tegenover zijn nageslacht, verband houdend met de opeenvolging van de genera- ties en de onvermijdelijkheid van het oud worden en de dood. In extreme vorm leidt dit tot een fysisch of psychisch doden van de zoon. De uitwerking van dit thema door Graham Greene vindt men in drie werken, de roman 'The Quiet American' (1955) en de toneelwerken 'The Potting Shed' (1958) en 'Carving a Statue' (1964). Ze zijn gepubliceerd binnen een tijdsperiode van tien jaar, samenvallend met de zesde levensdecade van de schrijver. Dit is de periode waarin de bewustwording van de eigen achteruitgang en het groeiende overwicht van de jeugd onvermijdelijk wordt. Wanneer we de chronologische volgorde van de werken in acht nemen, dan zien we dat in de motivering van de vaderfiguur het narcistische element progressief meer uitgesproken is. Daartegenover stellen we vast dat in de bijna tien jaar later gepubliceerde roman 'The Honorary Consul' (1973) de rivaliteit tussen een vaderfiguur en een zoonfiguur terug aan bod komt maar het vader-zoonconflict wordt er opgelost door wederzijdse aanvaarding en grootmoedigheid. Inleiding Toen Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams (Iwo) naar de Oedipusmy- the verwees als het prototype van de verdrongen verlangens van het kind om zijn moeder te huwen en zijn vader te doden, beperkte hij zich tot dat deel van de mythe dat wordt uitgebeeld in Oedipus Koning van Sophocles. -

Darkest Greeneland: Brighton Rock 133 Darkest Greeneland

Watts: Darkest Greeneland: Brighton Rock 133 Darkest Greeneland transformed it into Greeneland: a distinc- Darkest tively blighted, oppressive, tainted landscape, in which sordid, seedy and smelly details are Greeneland: prominent, and populated by characters who Brighton Rock include the corrupt, the failed, the vulgar, and the mediocre. In Brighton Rock, when the moon shines into Pinkie’s bedroom, it shines Cedric Watts on “the open door where the jerry stood”: on the Jeremiah, the chamber-pot.1 Later Dallow, The 1999 Graham Greene standing in the street, puts his foot in “dog’s International Festival ordure”: an everyday event in Brighton but an innovatory detail in literature. So far, so famil- On Greeneland iar. But Greene characteristically resisted the term he had helped to create. In his autobi- The term “Greeneland,” with an “e” before ographical book, Ways of Escape, he writes: the “l,” was apparently coined by Arthur Calder-Marshall. In an issue of the magazine Some critics have referred to a strange vio- Horizon for June 1940, Calder-Marshall said lent ‘seedy’ region of the mind (why did I that Graham Greene’s novels were character- ever popularize that last adjective?) which ised by a seedy terrain that should be called they call Greeneland, and I have sometimes “Greeneland.” I believe, however, that Greene, wondered whether they go round the world who enjoyed wordplay on his own surname, blinkered. ‘This is Indo-China,’ I want to had virtually coined the term himself. In the exclaim, ‘this is Mexico, this is Sierra Leone 1936 novel, A Gun for Sale, a crooner sings a carefully and accurately described. -

Graham Greene Studies, Volume 1

Stavick and Wise: Graham Greene Studies, Volume 1 Graham Greene Studies Volume 1, 2017 Graham Greene Birthplace Trust University of North Georgia Press Published by Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository, 2017 1 Graham Greene Studies, Vol. 1 [2017], Art. 1 Editors: Joyce Stavick and Jon Wise Editorial Board: Digital Editors: Jon Mehlferber Associate Editors: Ethan Howard Kayla Mehalcik Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia The University of North Georgia Press is a teaching press, providing a service-learning environment for students to gain real life experiences in publishing and marketing. The entirety of the layout and design of this volume was created and executed by Ethan Howard, a student at the University of North Georgia. Cover Photo Courtesy of Bernard Diederich For more information, please visit: http://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/ggs/ Copyright © 2017 by University of North Georgia Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a re- view in newspaper, magazine, or electronic publications; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other without the written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America, 2017 https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/ggs/vol1/iss1/1 2 Stavick and Wise: Graham Greene Studies, Volume 1 In Memory of David R.A. Pearce, scholar, poet, and friend David Pearce was born in Whitstable in 1938. -

The Third Man

Graham Greene - The Third Man A classic tale of friendship and betrayal William Golding I. Life of the author Henry Graham Greene was born on 2 October 1904 in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, England and was one of six children. At the age of eight he attended the Berkhamsted school where his father Charles was the head teacher. As a teenager he was under so immense pressure that he got psychological problems and suffered a nervous breakdown. In 1922 he was enrolled on the Balliol College, Oxford and in 1926 after graduation he started to work for the London Times as sub-editor and for the Nottingham Journal as journalist, where he met his later wife Vivien Dayrell-Browning. In February 1926 before marring his wife he was received into the Roman Catholic Church, which had influenced him and his writings (moral, religious, social themes). In 1929 his first novel The Man Within was published, so he became a freelance writer in 1930, but his popularity wasn´t sealed before Stamboul Train (Orient Express) was published in 1932. In 1935 he became the house film critic for The Spectator. In 1938 he published Brighton Rock and visited Mexico to report on the religious persecution there and as a result he wrote The Lawless Roads and The Power and the Glory. In 1940 he was promoted to literary editor for The Spectator. In 1941 - World War Two - he began to spy voluntarily for the British Foreign Office in Sierra Leone, western Africa and resigned in 1943 because of being accused of collusion and traitorous activities that never substantiated. -

Graham Greene's Thematic Usage of Good and Evil in Brighton Rock, the Power and the Glory

• ·-.~: RECORD, OF THESIS In partlal fulf5.llment of the requirement for the , i'f\p:jto,i ~ ~ degree, I hereby submit to the Dean of Gr.aduate Programs 62,.. · copies of my thes_is, each of whi.ch bears. ~he signatures of the members of my graduate COI'lll15. t tee. · I have paid the thesls binding fee to the Business 0 Offlce in the amount of $.\?. f , ~ $4.00 per copy, the . - receipt number for which is __.._f-=33=-l.o=----· ,/ !- , . '' . .- GRAHAM GREENE'S THEMATIC USAGE OF GOOD AND EVIL IN BRIGHTON ROCK, THE POWER AND THE GLORY, . AND-"THE-- HEAi'i'T ---OF THE MATTER • A Monograph Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Morehead State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Lynn Holbrook Stidham May 1973 .A:ccepted by .t~e faculty of the School 'of Hurua11 ;ft€r , · Morehead State University, in partial fulfillment of the req·uirements f-0r the Master. of _,_4:..:.ds"-=s'-------- degree. Master's Coinmittee: C/1 1?1.J (date) TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapte·r Page l. INTRODUCTION ••••••• t. • •••••••••.•••••••••••••••• o i· 2. THE THEMATIC USAGE OF GOOD AND EVIL IN BRIGHTON RO CK ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• e • • 5 g, THE THEMATIC USAGE OF GOOD AND EVIL IN THE POWER £:.liE THE GLORY , •• , ••••• , •• , • , ••.••• , • • 29 4. THE THEMATIC USAGE OF GOOD AND EVIL IN •. THE HEART OF THE MP. TTER •••••••••••••••••••••••• 53 s.· SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 73 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 75 .:. ' ... ~ Chepter·I INTRODUCTION Graham Greene has usually been considered a Catholic novelist because he is a Catholic convert and his work has often been _judged, not on literary bases, but instead, upon dogmatic approaches. -

Jan Kłos, Freedom As an Uncertain Cause in Graham

160 RECENZJE Warto zatem wróci do prostej prawdy na gruncie dyskusji o tosamoci wspó- czesnego uniwersytetu, przede wszystkim katolickiego: filozofia uczy uywania rozumu, a bez tej umiejtnoci trudno porusza si w oparach absurdu i gupoty wiata. Rezyg- nacja z jej nauczania jest równoznaczna z rezygnacj= uczenia tego, jak uywa rozumu. Anna Gb Katedra Historii Filozofii Nowoytnej i Wspóczesnej na Wydziale Filozofii KUL Jan K o s, Freedom as an Uncertain Cause in Graham Greene’s Novels: A Philosophical and Literary Analysis, Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL 2012. ISBN: 978-83-7702-542-0. Jan Kos, professor at the John Paul II Catholic University in Lublin, is an author of the first comprehensive study on Graham Greene (1904-1991) written in English and published in Poland. This Polish philosopher whose main interest is social and political ethics made every effort to provide a broad panorama of Greene’s literary and philo- sophical landscape, i.e. to show the theological, philosophical, and literary aspects of Graham Greene’s writing. Freedom as an Uncertain Cause in Graham Greene’s Novels was written by an author who competently (Kos studied both philosophy and English) discloses and describes the philosophical (mainly ethical) and theological threads hidden in different forms of Greene’s works. Who was Graham Greene? He was an English novelist, short-story writer, playwright, and journalist. After studying at Balliol College, Oxford, Greene converted to Roman Catholicism in 1926. This decision was partly made under the influence of his future wife, Vivien Dayrell-Browning, whom he married in 1927. Sometime later he moved to Lon- don, where he worked as a copy editor (1926-1930) on the editorial staff of The Times newspaper. -

Graham Greene: a Checklist

!"#$#%&!"''(')&*&+$',-./01 *21$3"405)&6/,$#"7&8#2'"&+301# 6'9/':'7&:3"-405) ;32",')&+3..'<'&=/1'"#12"'>&?3.@&AB>&C3@&A&4ADEF5>&GG@&EFHDI J2K./0$'7&KL)&College Literature ;1#K.'&M6=)&http://www.jstor.org/stable/25111648 . *,,'00'7)&ADNOANBOAP&AQ)BR Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. College Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to College Literature. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Sat, 19 Jan 2013 16:27:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions BIBLIOGRAPHY GRAHAM GREENE: A CHECKLIST by Richard Hauer Costa A en years ago, when Graham Greene was nearing his seventieth birthday, Philip Stratford in his introduction to The Portable Graham Greene wrote that his man "was drawing into perspective .... Few other complete men of letters have resisted definition better." The compilation of even a highly selective checklist of books by and about Graham Greene makes the sheer variety of his interests?and those of critics and scholars?apparent. How ever, his most recent book, the nonfiction memoir Getting to Know the General: The Story of an Involvement (published in the United States just after his eightieth birthday) reveals that the elder statesman of living British writers is as peripatetic as ever, travelling to far-off places, making a revolu tion?or the promise of one?a part of the action, and installing a hero?himself?who performs honorably despite a paralysis of the spirit. -

Graham Greene: a Descriptive Catalog

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, British Isles English Language and Literature 1979 Graham Greene: A Descriptive Catalog Robert H. Miller University of Louisville Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Miller, Robert H., "Graham Greene: A Descriptive Catalog" (1979). Literature in English, British Isles. 22. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_british_isles/22 Graham Greene: A Descriptive Catalog This page intentionally left blank GRAHAM GREENE A Descriptive Catalog ROBERT H. MILLER Foreword by Harvey Curtis Webster THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright© 1979 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Fuson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8131-9303-8 (pbk: acid-free paper) This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.