And Graham Greene: a Comparati Vb Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

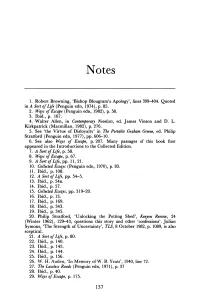

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Het Tains Motif in Het Werk Van Graham Greene

Het Tains Motif in het werk van Graham Greene door R.A. Pierloot Samenvatting In de psychoanalytische traditie werden vader-zoonconflicten beschouwd als het gevolg van rivaliteit en doodswensen uitgaande van de zoon. Maar sinds enkele ja- ren werd de aandacht getrokken op het bestaan van agressieve impulsen bij de vader tegenover zijn nageslacht, verband houdend met de opeenvolging van de genera- ties en de onvermijdelijkheid van het oud worden en de dood. In extreme vorm leidt dit tot een fysisch of psychisch doden van de zoon. De uitwerking van dit thema door Graham Greene vindt men in drie werken, de roman 'The Quiet American' (1955) en de toneelwerken 'The Potting Shed' (1958) en 'Carving a Statue' (1964). Ze zijn gepubliceerd binnen een tijdsperiode van tien jaar, samenvallend met de zesde levensdecade van de schrijver. Dit is de periode waarin de bewustwording van de eigen achteruitgang en het groeiende overwicht van de jeugd onvermijdelijk wordt. Wanneer we de chronologische volgorde van de werken in acht nemen, dan zien we dat in de motivering van de vaderfiguur het narcistische element progressief meer uitgesproken is. Daartegenover stellen we vast dat in de bijna tien jaar later gepubliceerde roman 'The Honorary Consul' (1973) de rivaliteit tussen een vaderfiguur en een zoonfiguur terug aan bod komt maar het vader-zoonconflict wordt er opgelost door wederzijdse aanvaarding en grootmoedigheid. Inleiding Toen Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams (Iwo) naar de Oedipusmy- the verwees als het prototype van de verdrongen verlangens van het kind om zijn moeder te huwen en zijn vader te doden, beperkte hij zich tot dat deel van de mythe dat wordt uitgebeeld in Oedipus Koning van Sophocles. -

Darkest Greeneland: Brighton Rock 133 Darkest Greeneland

Watts: Darkest Greeneland: Brighton Rock 133 Darkest Greeneland transformed it into Greeneland: a distinc- Darkest tively blighted, oppressive, tainted landscape, in which sordid, seedy and smelly details are Greeneland: prominent, and populated by characters who Brighton Rock include the corrupt, the failed, the vulgar, and the mediocre. In Brighton Rock, when the moon shines into Pinkie’s bedroom, it shines Cedric Watts on “the open door where the jerry stood”: on the Jeremiah, the chamber-pot.1 Later Dallow, The 1999 Graham Greene standing in the street, puts his foot in “dog’s International Festival ordure”: an everyday event in Brighton but an innovatory detail in literature. So far, so famil- On Greeneland iar. But Greene characteristically resisted the term he had helped to create. In his autobi- The term “Greeneland,” with an “e” before ographical book, Ways of Escape, he writes: the “l,” was apparently coined by Arthur Calder-Marshall. In an issue of the magazine Some critics have referred to a strange vio- Horizon for June 1940, Calder-Marshall said lent ‘seedy’ region of the mind (why did I that Graham Greene’s novels were character- ever popularize that last adjective?) which ised by a seedy terrain that should be called they call Greeneland, and I have sometimes “Greeneland.” I believe, however, that Greene, wondered whether they go round the world who enjoyed wordplay on his own surname, blinkered. ‘This is Indo-China,’ I want to had virtually coined the term himself. In the exclaim, ‘this is Mexico, this is Sierra Leone 1936 novel, A Gun for Sale, a crooner sings a carefully and accurately described. -

Graham Greene Studies, Volume 1

Stavick and Wise: Graham Greene Studies, Volume 1 Graham Greene Studies Volume 1, 2017 Graham Greene Birthplace Trust University of North Georgia Press Published by Nighthawks Open Institutional Repository, 2017 1 Graham Greene Studies, Vol. 1 [2017], Art. 1 Editors: Joyce Stavick and Jon Wise Editorial Board: Digital Editors: Jon Mehlferber Associate Editors: Ethan Howard Kayla Mehalcik Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia The University of North Georgia Press is a teaching press, providing a service-learning environment for students to gain real life experiences in publishing and marketing. The entirety of the layout and design of this volume was created and executed by Ethan Howard, a student at the University of North Georgia. Cover Photo Courtesy of Bernard Diederich For more information, please visit: http://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/ggs/ Copyright © 2017 by University of North Georgia Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a re- view in newspaper, magazine, or electronic publications; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other without the written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America, 2017 https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/ggs/vol1/iss1/1 2 Stavick and Wise: Graham Greene Studies, Volume 1 In Memory of David R.A. Pearce, scholar, poet, and friend David Pearce was born in Whitstable in 1938. -

A Philosophical and Literary Analysis, Lublin: Wyda

160 RECENZJE Warto zatem wróci4 do prostej prawdy na gruncie dyskusji o tobsamoVci wspó- czesnego uniwersytetu, przede wszystkim katolickiego: filozofia uczy ubywania rozumu , a bez tej umiejBtnoVci trudno porusza4 siB w oparach absurdu i gupoty Vwiata. Rezyg- nacja z jej nauczania jest równoznaczna z rezygnacj= uczenia tego, jak ubywa4 rozumu. Anna G=b Katedra Historii Filozofii Nowobytnej i Wspóczesnej na Wydziale Filozofii KUL Jan Kos, Freedom as an Uncertain Cause in Graham Greene’s Novels: A Philosophical and Literary Analysis , Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL 2012. ISBN: 978-83-7702-542-0. Jan Kos, professor at the John Paul II Catholic University in Lublin, is an author of the first comprehensive study on Graham Greene (1904-1991) written in English and published in Poland. This Polish philosopher whose main interest is social and political ethics made every effort to provide a broad panorama of Greene’s literary and philo- sophical landscape, i.e. to show the theological, philosophical, and literary aspects of Graham Greene’s writing. Freedom as an Uncertain Cause in Graham Greene’s Novels was written by an author who competently (Kos studied both philosophy and English) discloses and describes the philosophical (mainly ethical) and theological threads hidden in different forms of Greene’s works. Who was Graham Greene? He was an English novelist, short-story writer, playwright, and journalist. After studying at Balliol College, Oxford, Greene converted to Roman Catholicism in 1926. This decision was partly made under the influence of his future wife, Vivien Dayrell-Browning, whom he married in 1927. Sometime later he moved to Lon- don, where he worked as a copy editor (1926-1930) on the editorial staff of The Times newspaper. -

Graham Greene's Thematic Usage of Good and Evil in Brighton Rock, the Power and the Glory

• ·-.~: RECORD, OF THESIS In partlal fulf5.llment of the requirement for the , i'f\p:jto,i ~ ~ degree, I hereby submit to the Dean of Gr.aduate Programs 62,.. · copies of my thes_is, each of whi.ch bears. ~he signatures of the members of my graduate COI'lll15. t tee. · I have paid the thesls binding fee to the Business 0 Offlce in the amount of $.\?. f , ~ $4.00 per copy, the . - receipt number for which is __.._f-=33=-l.o=----· ,/ !- , . '' . .- GRAHAM GREENE'S THEMATIC USAGE OF GOOD AND EVIL IN BRIGHTON ROCK, THE POWER AND THE GLORY, . AND-"THE-- HEAi'i'T ---OF THE MATTER • A Monograph Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Morehead State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Lynn Holbrook Stidham May 1973 .A:ccepted by .t~e faculty of the School 'of Hurua11 ;ft€r , · Morehead State University, in partial fulfillment of the req·uirements f-0r the Master. of _,_4:..:.ds"-=s'-------- degree. Master's Coinmittee: C/1 1?1.J (date) TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapte·r Page l. INTRODUCTION ••••••• t. • •••••••••.•••••••••••••••• o i· 2. THE THEMATIC USAGE OF GOOD AND EVIL IN BRIGHTON RO CK ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• e • • 5 g, THE THEMATIC USAGE OF GOOD AND EVIL IN THE POWER £:.liE THE GLORY , •• , ••••• , •• , • , ••.••• , • • 29 4. THE THEMATIC USAGE OF GOOD AND EVIL IN •. THE HEART OF THE MP. TTER •••••••••••••••••••••••• 53 s.· SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 73 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 75 .:. ' ... ~ Chepter·I INTRODUCTION Graham Greene has usually been considered a Catholic novelist because he is a Catholic convert and his work has often been _judged, not on literary bases, but instead, upon dogmatic approaches. -

Jan Kłos, Freedom As an Uncertain Cause in Graham

160 RECENZJE Warto zatem wróci do prostej prawdy na gruncie dyskusji o tosamoci wspó- czesnego uniwersytetu, przede wszystkim katolickiego: filozofia uczy uywania rozumu, a bez tej umiejtnoci trudno porusza si w oparach absurdu i gupoty wiata. Rezyg- nacja z jej nauczania jest równoznaczna z rezygnacj= uczenia tego, jak uywa rozumu. Anna Gb Katedra Historii Filozofii Nowoytnej i Wspóczesnej na Wydziale Filozofii KUL Jan K o s, Freedom as an Uncertain Cause in Graham Greene’s Novels: A Philosophical and Literary Analysis, Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL 2012. ISBN: 978-83-7702-542-0. Jan Kos, professor at the John Paul II Catholic University in Lublin, is an author of the first comprehensive study on Graham Greene (1904-1991) written in English and published in Poland. This Polish philosopher whose main interest is social and political ethics made every effort to provide a broad panorama of Greene’s literary and philo- sophical landscape, i.e. to show the theological, philosophical, and literary aspects of Graham Greene’s writing. Freedom as an Uncertain Cause in Graham Greene’s Novels was written by an author who competently (Kos studied both philosophy and English) discloses and describes the philosophical (mainly ethical) and theological threads hidden in different forms of Greene’s works. Who was Graham Greene? He was an English novelist, short-story writer, playwright, and journalist. After studying at Balliol College, Oxford, Greene converted to Roman Catholicism in 1926. This decision was partly made under the influence of his future wife, Vivien Dayrell-Browning, whom he married in 1927. Sometime later he moved to Lon- don, where he worked as a copy editor (1926-1930) on the editorial staff of The Times newspaper. -

Graham Greene: a Descriptive Catalog

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, British Isles English Language and Literature 1979 Graham Greene: A Descriptive Catalog Robert H. Miller University of Louisville Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Miller, Robert H., "Graham Greene: A Descriptive Catalog" (1979). Literature in English, British Isles. 22. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_british_isles/22 Graham Greene: A Descriptive Catalog This page intentionally left blank GRAHAM GREENE A Descriptive Catalog ROBERT H. MILLER Foreword by Harvey Curtis Webster THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright© 1979 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Fuson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8131-9303-8 (pbk: acid-free paper) This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

Graham Greene's Od Depiction of Whisky Priest in the Power and The

Graham Greene’s od Depiction of Whisky Priest in The Power and the Glory S. Suma, M.A., B.Ed., M.Phil., Ph.D. Scholar (P.T.) Department of English & Comparative Literature, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai-625 021 ====================================================================== Abstract This paper is a fine attempt to portray Graham Greene’s literary skill in depicting the whisky priest both as religious and irreligious in his The Power and the Glory. This paper nearly presents how Greene distinguished Novels and entertainments. Thus, this paper examines the human qualities, devotion to duty, cathartic sufferings, belief in God’s glory and infinite mercy through the character of priest. Keywords: religious, morality, irreligious, church, temptations, sins, conflicts. Graham Greene is an attractive writer at various levels. It was Greene himself who first distinguished between his novels and his entertainments. His reasons for making this distinction were various; namely, that his novels were written slowly and entertainments quickly, that the novels were the products of depressive periods and entertainment manic, that the entertainments were crime stories and the novels something more. He remains a novelist in whom the changes are minor and the unity over-whelming. The locales of his novels may have changed, but the imagination has remained a constant from the beginning. He has done what he aimed at doing; he has expressed a religious sense and created a fictional world in which human acts are important. In that world, at least, creative art is a function of the religious mind. No doubt, Graham Greene is widely acclaimed as a writer with immense potentiality. -

Download the Return of AJ Raffles

The Return Of A. J. Raffles: An Edwardian comedy in three acts based somewhat loosely on E.W. Hornung's characters in The Amateur Cracksman, Graham Greene, Random House, 2011, 1446475999, 9781446475997, 252 pages. This play produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company has as its chief characters A. J. Raffles, the literary creation some seventy odd years ago of E. W. Hornung. The cool daring of the impeccable Amateur Cracksman, always torn between the rival claims of burglary and cricket, ensured his popularity in Edwardian England. Evading the dogged pursuit of Inspector Mackenzie of Scotland Yard, Hornung's character eventually met a hero's death in South Africa in the Boer War. Graham Greene's The Return of A. J. Raffles begins some months after. Raffles' loyal assistant Bunny still mourns his friend's death in Raffles' chambers in Albany, despite the blandishments of Lord Alfred Douglas. A visitor forces his way in - Raffles has cheated death as he once cheated Inspector Mackenzie - and immediately Lord Alfred sees in the Amateur Cracksman and Bunny heaven-sent instruments to revenge and disgrace of Oscar Wilde on his odious father, the Marquess of Queensberry... Graham Green never fails to surprise and delight admirers of his comic genius, and the twists and turns of this story of Edwardian high life, when Raffles returns to the scene of his earlier triumphs, provide a richly satisfying entertainment.. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1hYMFU7 21 stories , Graham Greene, 1969, Fiction, 245 pages. The Heart of the Matter , Graham Greene, 1978, Africa, 271 pages. An assistant police commissioner in a West African coastal town lets passion overrule his honor. -

Graham Greene

PERSPECTIVES Graham Greene This winter, Graham Greene's Ways of Escape, the long-awaited sequel to his first memoir, A Sort of Life (1971) will be published in New York. In the new book, the British novelist assembles a pastiche of recollections of his adventures around the world dur- ing the past 50 years-exploits that resulted in such vivid novels as The Power and the Glory, The Heart of the Matter, The Quiet American, and Our Man in Havana. Yet Greene has always brought a special dimension of faith to his novels. Here critic Frank McConnell reassesses Greene's penchant for "action" and "belief"-his long prolific career, his devotion to Catholicism and socialism, and his affinity with the movies. Selections from Greene's own writings follow. by Frank D. McConnell Imagine a not-quite young, not-quite happy man with a te- dious and/or dangerous job in a seedy, urban or colonial, locale. Now, imagine that something happens to force him to be- tray whatever is dearest to him-a loved one, an ideal, a creed. In the aftermath of his faithlessness, he comes to discover pre- cisely how dear was the person or thing he betrayed. In the corrosive admission of his failure, he learns, if he is lucky, to re- build his broken image of the world and to find his place in it. Now add scenes of grotesque violence and grim comedy, in- cidental characters (tawdry, sinister, and dotty), and a limpid prose style. You have, of course, conjured up any of the 23 novels of Graham Greene. -

Přechodné Období

PŘECHODNÉ OBDOBÍ 1 Po období let válečných a poválečných, kdy výrazným momentem v Greenově tvorbě byla problematika náboženská, se léta padesátá a po čátek let šedesátých jeví jako jakési období přechodné, ukazující již ně kterými rysy na období poslední. Zhruba od poloviny 50. let náboženská tématika postupně ztrácí ústřední postavení nebo je novým způsobem — kriticky až ironicky či parodicky — traktována. Ustupují tóny chmurné a na intenzitě získává komediální vidění světa. Významnou úlohu počínají hrát osvobozenecká hnutí třetího světa, postupně sílí autorův antiameri- kanismus. Ke změně Greenova celkového zaměření přispěla nepochybně řada faktorů. K nejdůležitějším z nich patří uvolňování napětí v Evropě a vnitřní pohyb v katolické církvi, demonstrovaný druhým vatikánským koncilem. Velký vliv na to, že Greene nyní přitakává tomuto světu, měla pro něho četba spisů Teilharda de Chardin. Bez významu pro autorův vývoj není postupný rozpad starých koloniálních říší. Patří sem především romány Prohrávající získává všechno (Loser Takés AU, 1955), Tichý Američan (The Quiet American, 1955), Náš člověk v Ha vaně (Our Man in Havana, 1958) a Vyhaslý případ (A Burnt-Out Case, 1961). Z povídek Pornografický film (The Blue Film, 1954), Zvláštní úkoly {Speciál Duties, 1954) a Ničitelé (The Destructors, 1954), z dramat Skleník (The Potting Shed, 1957) a Shovívavý milenec (The Complaisant Lover, 1959). 2 V lehkém tónu napsaný román Prohrávající získává všechno (Loser Takés AU, 1955) je oddechovým dílem. Hrdinou je účetní Bertram, schop ný matematik a kombinátor, který se podruhé žení a kterého jeho šéf pozve do Monaka na svou jachtu. Bertram se v kasinu pokusí hrát a díky systému, který vymyslel, hodně vyhrává a bohatne, avšak manželka Cary 41 se mu počne odcizovat.