Graham Greene's the Living Room: an Uncomfortable Catholic Play In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

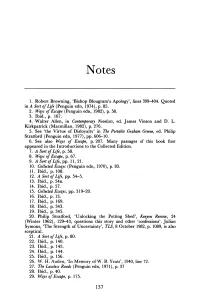

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

THE CATHOLIC TREATMENT OP SIN and REDEMPTION in the NOVELS of GRAHAM GREENE by Thomas M„ Sheehan

UNIVERSITY D'OTTAWA » ECOLE PES GRADUE5 .. / THE CATHOLIC TREATMENT OP SIN AND REDEMPTION IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE by Thomas M„ Sheehan Thesis presented to the English Department of the Graduate School of the faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy *****$*# *$> Ottawa, Canada and Louisville, Kentucky I960 UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA - SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: DC53535 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53535 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 UNIVERSITE D'OTTAWA - ECOLE DES GRADUES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis was prepared under the supervision of Dr. Emmett 0'Grady, Head of the English Department of the University of Ottawa. The writer is indebted t© Mr. P. B. Lysaght of London, England for invaluable material on Graham Greene that was not readily available either in the United States or in Canada. The writer is also indebted to the librar ians of Nazareth College, and Sellarmine College, Louisville, Kentucky for the use of their facilities. -

A Philosophical and Literary Analysis, Lublin: Wyda

160 RECENZJE Warto zatem wróci4 do prostej prawdy na gruncie dyskusji o tobsamoVci wspó- czesnego uniwersytetu, przede wszystkim katolickiego: filozofia uczy ubywania rozumu , a bez tej umiejBtnoVci trudno porusza4 siB w oparach absurdu i gupoty Vwiata. Rezyg- nacja z jej nauczania jest równoznaczna z rezygnacj= uczenia tego, jak ubywa4 rozumu. Anna G=b Katedra Historii Filozofii Nowobytnej i Wspóczesnej na Wydziale Filozofii KUL Jan Kos, Freedom as an Uncertain Cause in Graham Greene’s Novels: A Philosophical and Literary Analysis , Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL 2012. ISBN: 978-83-7702-542-0. Jan Kos, professor at the John Paul II Catholic University in Lublin, is an author of the first comprehensive study on Graham Greene (1904-1991) written in English and published in Poland. This Polish philosopher whose main interest is social and political ethics made every effort to provide a broad panorama of Greene’s literary and philo- sophical landscape, i.e. to show the theological, philosophical, and literary aspects of Graham Greene’s writing. Freedom as an Uncertain Cause in Graham Greene’s Novels was written by an author who competently (Kos studied both philosophy and English) discloses and describes the philosophical (mainly ethical) and theological threads hidden in different forms of Greene’s works. Who was Graham Greene? He was an English novelist, short-story writer, playwright, and journalist. After studying at Balliol College, Oxford, Greene converted to Roman Catholicism in 1926. This decision was partly made under the influence of his future wife, Vivien Dayrell-Browning, whom he married in 1927. Sometime later he moved to Lon- don, where he worked as a copy editor (1926-1930) on the editorial staff of The Times newspaper. -

The Third Man

Graham Greene - The Third Man A classic tale of friendship and betrayal William Golding I. Life of the author Henry Graham Greene was born on 2 October 1904 in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, England and was one of six children. At the age of eight he attended the Berkhamsted school where his father Charles was the head teacher. As a teenager he was under so immense pressure that he got psychological problems and suffered a nervous breakdown. In 1922 he was enrolled on the Balliol College, Oxford and in 1926 after graduation he started to work for the London Times as sub-editor and for the Nottingham Journal as journalist, where he met his later wife Vivien Dayrell-Browning. In February 1926 before marring his wife he was received into the Roman Catholic Church, which had influenced him and his writings (moral, religious, social themes). In 1929 his first novel The Man Within was published, so he became a freelance writer in 1930, but his popularity wasn´t sealed before Stamboul Train (Orient Express) was published in 1932. In 1935 he became the house film critic for The Spectator. In 1938 he published Brighton Rock and visited Mexico to report on the religious persecution there and as a result he wrote The Lawless Roads and The Power and the Glory. In 1940 he was promoted to literary editor for The Spectator. In 1941 - World War Two - he began to spy voluntarily for the British Foreign Office in Sierra Leone, western Africa and resigned in 1943 because of being accused of collusion and traitorous activities that never substantiated. -

Jan Kłos, Freedom As an Uncertain Cause in Graham

160 RECENZJE Warto zatem wróci do prostej prawdy na gruncie dyskusji o tosamoci wspó- czesnego uniwersytetu, przede wszystkim katolickiego: filozofia uczy uywania rozumu, a bez tej umiejtnoci trudno porusza si w oparach absurdu i gupoty wiata. Rezyg- nacja z jej nauczania jest równoznaczna z rezygnacj= uczenia tego, jak uywa rozumu. Anna Gb Katedra Historii Filozofii Nowoytnej i Wspóczesnej na Wydziale Filozofii KUL Jan K o s, Freedom as an Uncertain Cause in Graham Greene’s Novels: A Philosophical and Literary Analysis, Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL 2012. ISBN: 978-83-7702-542-0. Jan Kos, professor at the John Paul II Catholic University in Lublin, is an author of the first comprehensive study on Graham Greene (1904-1991) written in English and published in Poland. This Polish philosopher whose main interest is social and political ethics made every effort to provide a broad panorama of Greene’s literary and philo- sophical landscape, i.e. to show the theological, philosophical, and literary aspects of Graham Greene’s writing. Freedom as an Uncertain Cause in Graham Greene’s Novels was written by an author who competently (Kos studied both philosophy and English) discloses and describes the philosophical (mainly ethical) and theological threads hidden in different forms of Greene’s works. Who was Graham Greene? He was an English novelist, short-story writer, playwright, and journalist. After studying at Balliol College, Oxford, Greene converted to Roman Catholicism in 1926. This decision was partly made under the influence of his future wife, Vivien Dayrell-Browning, whom he married in 1927. Sometime later he moved to Lon- don, where he worked as a copy editor (1926-1930) on the editorial staff of The Times newspaper. -

Graham Greene: a Checklist

!"#$#%&!"''(')&*&+$',-./01 *21$3"405)&6/,$#"7&8#2'"&+301# 6'9/':'7&:3"-405) ;32",')&+3..'<'&=/1'"#12"'>&?3.@&AB>&C3@&A&4ADEF5>&GG@&EFHDI J2K./0$'7&KL)&College Literature ;1#K.'&M6=)&http://www.jstor.org/stable/25111648 . *,,'00'7)&ADNOANBOAP&AQ)BR Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. College Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to College Literature. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded on Sat, 19 Jan 2013 16:27:50 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions BIBLIOGRAPHY GRAHAM GREENE: A CHECKLIST by Richard Hauer Costa A en years ago, when Graham Greene was nearing his seventieth birthday, Philip Stratford in his introduction to The Portable Graham Greene wrote that his man "was drawing into perspective .... Few other complete men of letters have resisted definition better." The compilation of even a highly selective checklist of books by and about Graham Greene makes the sheer variety of his interests?and those of critics and scholars?apparent. How ever, his most recent book, the nonfiction memoir Getting to Know the General: The Story of an Involvement (published in the United States just after his eightieth birthday) reveals that the elder statesman of living British writers is as peripatetic as ever, travelling to far-off places, making a revolu tion?or the promise of one?a part of the action, and installing a hero?himself?who performs honorably despite a paralysis of the spirit. -

Graham Greene: a Descriptive Catalog

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, British Isles English Language and Literature 1979 Graham Greene: A Descriptive Catalog Robert H. Miller University of Louisville Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Miller, Robert H., "Graham Greene: A Descriptive Catalog" (1979). Literature in English, British Isles. 22. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_british_isles/22 Graham Greene: A Descriptive Catalog This page intentionally left blank GRAHAM GREENE A Descriptive Catalog ROBERT H. MILLER Foreword by Harvey Curtis Webster THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright© 1979 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2009 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Fuson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8131-9303-8 (pbk: acid-free paper) This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

Graham Greene

Graham Greene: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Greene, Graham1904-1991 Title: Graham Greene Collection Dates: 1924-1998 Extent: 96 boxes (40 linear feet), 7 galley folders, and 3 oversize folders Abstract: The collection consists primarily of holograph and typescript manuscripts for many of Greene's major works, personal diaries and datebooks, and correspondence. Also present are files kept by Greene's publisher Laurence Pollinger, including correspondence and records of contract negotiations. Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Gifts and purchases, 1964-1997 Processed by: Chelsea Dinsmore, 2002 Provenance The majority of the Graham Greene manuscript materials were acquired in the early 1970s while various individual items and small groups were purchased between 1964 and 1997. The Laurence Pollinger correspondence files were obtained as part of a separate purchase in 1994. Repository: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin Greene, Graham 1904-1991 Biographical Sketch Born in Berkhamstead, England, in 1904, Henry Graham Green was the fourth of six children born to Charles Henry and Marion Raymond Greene. Greene led a fairly typical childhood for the time, raised largely by nurses and nannies in the nursery and spending relatively little time with his parents. His father held a position as a headmaster at the Berkhamstead School giving Graham an early taste of divided loyalties when he entered the school in 1915. At the age of sixteen Graham had a mental crisis during which he ran away from home and school. Coming on top of several questionable suicide attempts and exaggerated illnesses, his parents sent him for six months of psychoanalysis. -

Graham Greene Papers 1807-1999 (Bulk 1940-1989) MS.1995.003 Hdl.Handle.Net/2345/7753

Graham Greene Papers 1807-1999 (bulk 1940-1989) MS.1995.003 hdl.handle.net/2345/7753 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 8 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................... 10 I: Art, artifacts, and ephemera .................................................................................................................. 10 II: Auctions and manuscript -

David Hawksworth's Graham Greene Collection

DAVID HAWKSWORTH’S GRAHAM GREENE COLLECTION. Graham Greene is my favourite writer and I have been reading and collecting his books since the early 1990’s. Looking back and as far as I can remember the first book I read was ‘Brighton Rock’. The book was a Penguin edition published in 1970. Below is the cover of this edition. It cost DM 15.90. I am not sure which book came next but it may have been ‘Stamboul Train’. This again was a Penguin edition but in the series ‘Penguin Twentieth Century Classics’. The cover is below. I bought other Graham Greene books from the same series which all carried similar formats but as my reading of his increased I just bought books in the edition available. So how did collecting Graham Greene books come about? I think it began with a day trip with my sister Celia to Hay-on-Wye. Again it must have been in the early 1990s. We were going in and out of book shops looking no doubt for Graham Greene books to read not to collect and I came upon a short story book ‘May we borrow your Husband and other comedies of the sexual life’. Could such a book exist? What and it costs £25.00. I just had to buy it and I think that is when my Graham Greene journey really started. 1 What I would like to do is show you many of the books written by Graham Greene which I have in my collection and if I can remember rightly how they came into my procession. -

Graham Green Graham Greene a Selection

presents Graham Greene a selection PETER HARRINGTON 100 Fulham Road London SW3 6HS Tel +44 (0)20 7591 0220 Fax +44 (0)20 7225 7054 [email protected] Browse our stock at www.peterharrington.co.uk We offer free shipping on website orders Members, ABA, ILAB, PBFA, ImCos, LAPADA 1. GREENE, Graham. Babbling April. Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1925 [48448] Octavo. Original grey boards, titles to upper board and spine in blue. With the dust jacket. A superb copy in the minimally tanned dust jacket and remains of the original glassine. £6,500 First Edition, Sole Impression of the author’s first book - a collection of poems written as an undergraduate at Oxford University. Just 300 copies were printed. Rare in this condition. 2. GREENE, Graham. The Man Within. Heinemann, London, 1929 [51654] Octavo. Original black cloth, titles to spine gilt. With the dust jacket. Spine very lightly rolled but an excellent copy in the rather rubbed and somewhat tanned dust jacket with some tape residue to the verso. £2,750 First edition, first impression. Greene’s first novel, preceded only by a slim volume of poetry. 3. GREENE, Graham. The Name of Action. London: William Heinemann Ltd, 1930 [51814] Octavo. Original blue cloth, titles to spine gilt. Foxing to edges, endpapers, and title pages. A very good copy. £500 First edition, first impression. 4. GREENE, Graham. Rumour at Nightfall. London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1931 [52068] Octavo. Original red cloth, titles to spine gilt, blind stamped star motif to upper board. Slight fading to spine, a few minor marks to boards, otherwise an internally fresh, bright copy.