Basque Language Loyalism at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Connections Between Sámi and Basque Peoples

Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Kent Randell 2012 Siidastallan Outside of Minneapolis, Minneapolis Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota “D----- it Jim, I’m a librarian and an armchair anthropologist??” Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Connections between Sámi and Basque Peoples Hard evidence: - mtDNA - Uniqueness of language Other things may be surprising…. or not. It is fun to imagine other connections, understanding it is not scientific Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Documentary: Suddenly Sámi by Norway’s Ellen-Astri Lundby She receives her mtDNA test, and express surprise when her results state that she is connected to Spain. This also surprised me, and spurned my interest….. Then I ended up living in Boise, Idaho, the city with the largest concentration of Basque outside of Basque Country Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota What is mtDNA genealogy? The DNA of the Mitochondria in your cells. Cell energy, cell growth, cell signaling, etc. mtDNA – At Conception • The Egg cell Mitochondria’s DNA remains the same after conception. • Male does not contribute to the mtDNA • Therefore Mitochondrial mtDNA is the same as one’s mother. Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, Linwood Township, Minnesota Four generation mtDNA line Sisters – Mother – Maternal Grandmother – Great-grandmother Jennie Mary Karjalainen b. Kent21 Randell March (c) 2012 1886, --- 2012 Siidastallan,parents from Kuusamo, Finland Linwood Township, Minnesota Isaac Abramson and Jennie Karjalainen wedding picture Isaac is from Northern Norway, Kvaen father and Saami mother from Haetta Kent Randell (c) 2012 --- 2012 Siidastallan, village. -

Reuniónes Informativas. Valoración Final

BIZKAIKO BASOGINTZA ELKARTEA Galdakao, 28 de diciembre de 2018 REUNIÓNES INFORMATIVAS. VALORACIÓN FINAL Gestión de la situación sanitaria de los pinares en el T.H. de Bizkaia MARKINA – GERNIKA – IURRETA – OROZKO - SODUPE A lo largo de las dos últimas semanas del mes de diciembre se han celebrado en las diferentes comarcas del Territorio Histórico de Bizkaia varias reuniones informativas cuyo objeto, ha sido informar sobre la gestión de la situación sanitaria de los pinares, abarcando las principales inquietudes que nos trasladan nuestros socios y socias y propietarios y propietarias forestales, las cuales se agrupan en cuatro grandes bloques: “Tratamiento preventivo y control de la enfermedad”, “Ayudas a la reparación de los daños”, “Mercado de la madera y gestión empresarial en la coyuntura actual” y “Próximo ciclo forestal después de la tala- Especies alternativas.” Para tratar estos temas se ha contado con la presencia de la Diputada Foral de Sostenibilidad y Medio Natural de la Diputación Foral de Bizkaia, Elena Unzueta, el Asesor General del Departamento de Sostenibilidad y Medio Natural de la Diputación Foral de Bizkaia, Fernando Azurmendi, el Director de Calidad e Industrias Alimentarias del Gobierno Vasco, Peli Manterola, el Presidente y Director General de Baskegur, Federico Saiz y Oskar Azkarate respectivamente y el Presidente y el Director de la Asociación de Forestalistas de Bizkaia, Jose Antonio Zabala y Eduardo Rodríguez respectivamente, los cuales realizaron sus ponencias y contestaron a las diferentes cuestiones que se expusieron en la parte de ruegos, preguntas y posterior debate. 1 BIZKAIKO BASOGINTZA ELKARTEA La enfermedad denominada “Banda marrón” que provoca la defoliación de los pinos, principalmente de la especie Pino radiata, ha sido el motivo de estas convocatorias a los propietarios y propietarias forestales. -

How Can a Modern History of the Basque Country Make Sense? on Nation, Identity, and Territories in the Making of Spain

HOW CAN A MODERN HISTORY OF THE BASQUE COUNTRY MAKE SENSE? ON NATION, IDENTITY, AND TERRITORIES IN THE MAKING OF SPAIN JOSE M. PORTILLO VALDES Universidad del Pais Vasco Center for Basque Studies, University of Nevada (Reno) One of the more recurrent debates among Basque historians has to do with the very object of their primary concern. Since a Basque political body, real or imagined, has never existed before the end of the nineteenth century -and formally not until 1936- an «essentialist» question has permanently been hanging around the mind of any Basque historian: she might be writing the histo- ry of an non-existent subject. On the other hand, the heaviness of the «national dispute» between Basque and Spanish identities in the Spanish Basque territories has deeply determined the mean- ing of such a cardinal question. Denying the «other's» historicity is a very well known weapon in the hands of any nationalist dis- course and, conversely, claiming to have a millenary past behind one's shoulders, or being the bearer of a single people's history, is a must for any «national» history. Consequently, for those who consider the Spanish one as the true national identity and the Basque one just a secondary «decoration», the history of the Basque Country simply does not exist or it refers to the last six decades. On the other hand, for those Basques who deem the Spanish an imposed identity, Basque history is a sacred territory, the last refuge for the true identity. Although apparently uncontaminated by politics, Basque aca- demic historiography gently reproduces discourses based on na- - 53 - ESPANA CONTEMPORANEA tionalist assumptions. -

Pais Vasco 2018

The País Vasco Maribel’s Guide to the Spanish Basque Country © Maribel’s Guides for the Sophisticated Traveler ™ August 2018 [email protected] Maribel’s Guides © Page !1 INDEX Planning Your Trip - Page 3 Navarra-Navarre - Page 77 Must Sees in the País Vasco - Page 6 • Dining in Navarra • Wine Touring in Navarra Lodging in the País Vasco - Page 7 The Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve - Page 84 Festivals in the País Vasco - Page 9 • Staying in the Urdaibai Visiting a Txakoli Vineyard - Page 12 • Festivals in the Urdaibai Basque Cider Country - Page 15 Gernika-Lomo - Page 93 San Sebastián-Donostia - Page 17 • Dining in Gernika • Exploring Donostia on your own • Excursions from Gernika • City Tours • The Eastern Coastal Drive • San Sebastián’s Beaches • Inland from Lekeitio • Cooking Schools and Classes • Your Western Coastal Excursion • Donostia’s Markets Bilbao - Page 108 • Sociedad Gastronómica • Sightseeing • Performing Arts • Pintxos Hopping • Doing The “Txikiteo” or “Poteo” • Dining In Bilbao • Dining in San Sebastián • Dining Outside Of Bilbao • Dining on Mondays in Donostia • Shopping Lodging in San Sebastián - Page 51 • Staying in Bilbao • On La Concha Beach • Staying outside Bilbao • Near La Concha Beach Excursions from Bilbao - Page 132 • In the Parte Vieja • A pretty drive inland to Elorrio & Axpe-Atxondo • In the heart of Donostia • Dining in the countryside • Near Zurriola Beach • To the beach • Near Ondarreta Beach • The Switzerland of the País Vasco • Renting an apartment in San Sebastián Vitoria-Gasteiz - Page 135 Coastal -

Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Center welcomes Gloria Totoricagüena New faculty member Gloria Totoricagüena started to really compare and analyze their FALL began working at the Center last spring, experiences, to look at the similarities and having recently completed her Ph.D. in differences between that Basque Center and 2002 Comparative Politics. Following is an inter- Basque communities in the U.S. So that view with Dr. Totoricagüena by editor Jill really started my academic interest. Al- Berner. though my Master’s degree was in Latin American politics and economic develop- NUMBER 66 JB: How did your interest in the Basque ment, the experience there gave me the idea diaspora originate and develop? GT: I really was born into it, I’ve lived it all my life. My parents are survivors of the In this issue: bombing of Gernika and were refugees to different parts of the Basque Country. And I’ve also lived the whole sheepherder family Gloria Totoricagüena 1 experience that is so common to Basque identity in the U.S. My father came to the Eskerrik asko! 3 U.S. as a sheepherder, and then later went Slavoj Zizek lecture 4 back to Gernika where he met my mother and they married and came here. My parents went Politics after 9/11 5 back and forth actually, and eventually settled Highlights in Boise. So this idea of transnational iden- 6 tity, and multiculturalism, is not new at all to Visiting scholars 7 me. -

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939

Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor A Thesis in the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts (History) at Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada March 2019 © Kyle McCreanor, 2019 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Kyle McCreanor Entitled: Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (History) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________ Chair Dr. Andrew Ivaska _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Ted McCormick _________________________________ Examiner Dr. Cameron Watson _________________________________ Supervisor Dr. Gavin Foster Approved by _________________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______________ 2019 _________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ireland and the Basque Country: Nationalisms in Contact, 1895-1939 Kyle McCreanor This thesis examines the relationships between Irish and Basque nationalists and nationalisms from 1895 to 1939—a period of rapid, drastic change in both contexts. In the Basque Country, 1895 marked the birth of the Partido Nacionalista Vasco (Basque Nationalist Party), concurrent with the development of the cultural nationalist movement known as the ‘Gaelic revival’ in pre-revolutionary Ireland. In 1939, the Spanish Civil War ended with the destruction of the Spanish Second Republic, plunging Basque nationalism into decades of intense persecution. Conversely, at this same time, Irish nationalist aspirations were realized to an unprecedented degree during the ‘republicanization’ of the Irish Free State under Irish leader Éamon de Valera. -

Basque Studies

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Basque Literature Series launched at Frankfurt Book Fair FALL Reported by Mari Jose Olaziregi director of Literature across Frontiers, an 2004 organization that promotes literature written An Anthology of Basque Short Stories, the in minority languages in Europe. first publication in the Basque Literature Series published by the Center for NUMBER 70 Basque Studies, was presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair October 19–23. The Basque Editors’ Association / Euskal Editoreen Elkartea invited the In this issue: book’s compiler, Mari Jose Olaziregi, and two contributors, Iban Zaldua and Lourdes Oñederra, to launch the Basque Literature Series 1 book in Frankfurt. The Basque Government’s Minister of Culture, Boise Basques 2 Miren Azkarate, was also present to Kepa Junkera at UNR 3 give an introductory talk, followed by Olatz Osa of the Basque Editors’ Jauregui Archive 4 Association, who praised the project. Kirmen Uribe performs Euskal Telebista (Basque Television) 5 was present to record the event and Highlights 6 interview the participants for their evening news program. (from left) Lourdes Oñederra, Iban Zaldua, and Basque Country Tour 7 Mari Jose Olaziregi at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Research awards 9 Prof. Olaziregi explained to the [photo courtesy of I. Zaldua] group that the aim of the series, Ikasi 2005 10 consisting of literary works translated The following day the group attended the Studies Abroad in directly from Basque to English, is “to Fair, where Ms. Olaziregi met with editors promote Basque literature abroad and to and distributors to present the anthology and the Basque Country 11 cross linguistic and cultural borders in order discuss the series. -

Elko Jaietan 51 Urte Celebrating 51 Years of Basque Tradition Schedule of Events

2014 Elko Jaietan 51 Urte Celebrating 51 Years of Basque Tradition Schedule of Events 2014 Elko Jaietan 51 Urte 2014 Elko Basque Festival Celebrating 51 Years Friday July 4th/Ostirala 4an Uztaila 6:00 p.m. – Kickoff/Txupinazua- Elko Basque Clubhouse Enjoy the evening with your family and friends with a taste of what is to come during the weekend. There will be dancing by the Elko Ariñak dancers, a Paella contest, Basque sport exhibitions of weight lifting and wood chopping, and handball games. Stay for exceptional food, drink, bounce house, and a special performance by this year’s Udaleku group. Saturday July 5th/Larunbata 5an Uztaila 7:00 a.m. – 5K Run/Walk – Eusko Etxtea – Elko Basque Club- house $20 participation fee and you get a t-shirt Registration is at 6:15 a.m. Race starts at 7:00 a.m. For more information contact Cody Krenka at 738-6479 11:00 a.m. – Parade – Downtown Elko 1:00 p.m. - Games & Dancing – Elko County Fairgrounds $10 Adults $5 Children 12 & Under Featuring the following dance groups: Elko Ariñak, Utah’ko Triskalariak, Reno Zazpiak Bat, and Ardi Baltza. Watch traditional Basque rural sports featuring weightlifting, wood chopping, weight carrying, relay, tug o war, and more! 2 9 p.m. Dance - Eusko Etxea - Elko Basque Clubhouse $12 Admission Dance - featuring Boise’s Amuma Says No; come enjoy a fun filled evening of dancing, catching up with old friends and making new ones Sunday July 6th /Igandea 6an Uztaila Eusko Etxea - Elko Basque Clubhouse Please NO outside Food or Beverage 10:30 a.m. -

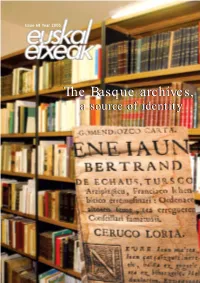

The Basquebasque Archives,Archives, Aa Sourcesource Ofof Identityidentity TABLE of CONTENTS

Issue 68 Year 2005 TheThe BasqueBasque archives,archives, aa sourcesource ofof identityidentity TABLE OF CONTENTS GAURKO GAIAK / CURRENT EVENTS: The Basque archives, a source of identity Issue 68 Year 3 • Josu Legarreta, Basque Director of Relations with Basque Communities. The BasqueThe archives,Basque 4 • An interview with Arantxa Arzamendi, a source of identity Director of the Basque Cultural Heritage Department 5 • The Basque archives can be consulted from any part of the planet 8 • Classification and digitalization of parish archives 9 • Gloria Totoricagüena: «Knowledge of a common historical past is essential to maintaining a people’s signs of identity» 12 • Urazandi, a project shining light on Basque emigration 14 • Basque periodicals published in Venezuela and Mexico Issue 68. Year 2005 ARTICLES 16 • The Basque "Y", a train on the move 18 • Nestor Basterretxea, sculptor. AUTHOR A return traveller Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo Harremanetarako Idazkaritza 20 • Euskaditik: The Bishop of Bilbao, elected Nagusia President of the Spanish Episcopal Conference Basque Government-General 21 • Euskaditik: Election results Secretariat for Foreign Action 22 • Euskal gazteak munduan / Basque youth C/ Navarra, 2 around the world 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Nestor Basterretxea Telephone: 945 01 7900 [email protected] DIRECTOR EUSKAL ETXEAK / ETXEZ ETXE Josu Legarreta Bilbao COORDINATION AND EDITORIAL 24 • Proliferation of programs in the USA OFFICE 26 • Argentina. An exhibition for the memory A. Zugasti (Kazeta5 Komunikazioa) 27 • Impressions of Argentina -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses Summer 7-14-2011 The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation Kalyna Macko Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Macko, Kalyna, "The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation" (2011). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 68. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/68 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Macko 1 The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation By: Kalyna Macko Pell Senior Thesis Primary Advisor: Dr. Jane Bethune Secondary Advisor: Dr. Clark Merrill Macko 2 Macko 3 Thesis Statement: The combined nationalist sentiments and opposition of these particular Basques to the Fascist regime of General Franco explained the violence of the terrorist group ETA both throughout his rule and into the twenty-first century. I. Introduction II. Basque Differences A. Basque Language B. Basque Race C. Conservative Political Philosophy III. The Formation of the PNV A. Sabino Arana y Goiri B. Re-Introduction of the Basque Culture C. The PNV as a Representation of the Basques IV. The Oppression of the Basques A. Targeting the Basques B. Primo de Rivera C. General Francisco Franco D. Bombing of Guernica E.