Ferro's El Otro Joyce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Refugio Seguro

REFUGIO SEGURO | COL REFUGIO SEGURO Albergar a personas desplazadas por violencia basada en género OMBIA CASO DE ESTUDIO Centro de Derechos Humanos , CASO DE ESTUDIO: COLOMBIA MAYO DE 2013 CENTRO DE DERECHOS HUMANOS | PROGRAMA DE VIOLENCIA SEXUAL Universidad de California, Berkeley, Facultad de Derecho 2013 Este estudio de cuatro países fue realizado como parte del Programa de Violencia Sexual del Centro de Derechos Humanos de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad de California, Berkeley. El ensayo fue escrito por Sara Feldman. El Centro de Derechos Humanos de la Facultad de Derecho de la Universidad de California, Berke- ley, realiza investigaciones sobre crímenes de guerra y otras violaciones graves de las leyes humani- tarias internacionales y los derechos humanos. Al usar métodos basados en evidencia y tecnologías innovadoras, apoyamos los esfuerzos por hacer rendir cuentas a los criminales y por proteger a la población vulnerable. También entrenamos a estudiantes y abogados en la documentación de las viola- ciones de derechos humanos y a convertir esta información en acciones concretas. Se puede encontrar más información sobre nuestros proyectos en: http://hrc.berkeley.edu. El Programa de Violencia Sexual busca mejorar la protección y el apoyo a sobrevivientes de conflictos relacionados con violencia de género; para ello propicia encuentros con diseñadores de políticas y otros profesionales similares que acuden con recomendaciones sobre responsabilidad y mecanismos de pro- tección basados en evidencia. Este estudio de cuatro países tiene como propósito iniciar la discusión sobre los tipos de amparo temporal disponibles para individuos que huyen de violencia por motivos de género en escenarios de desplazamiento tales como campos de refugiados o comunidades desplazadas internamente. -

Límites De Género En El Programa De Aldeas Para Repatriados En Burundi Yolanda Weima

Pensando en el futuro: desplazamiento, transición, soluciones 61 RMF 52 mayo 2016 www.fmreview.org/es/soluciones Límites de género en el programa de aldeas para repatriados en Burundi Yolanda Weima Aunque oficialmente la repatriación de refugiados se considera un retorno a las fronteras de su país de ciudadanía, “el hogar” para los repatriados debe analizarse con otros parámetros. El género y el parentesco se cruzan con muchos otros factores importantes en las diferentes experiencias de retorno. Después del conflicto en 1972, y tras una larga forma adecuada a los servicios básicos. década de guerra civil que comenzó en los El programa de VRI posterior adoptó un noventa, alrededor de un millón de burundeses enfoque más holístico, al proporcionar tierra buscaron refugio en países vecinos, en especial —aunque muchas familias aún tenían que Tanzania. Tras la firma de los acuerdos de recibir tierras cultivables— e incluir varios paz en el año 2000, los posteriores alto al proyectos de apoyo, con la expectativa de fuego y los cambios en la políticas de asilo una integración sostenible a largo plazo para regionales y mundiales, más 700 000 refugiados los repatriados en un entorno mayormente regresaron a Burundi entre 2002 y 2009. agrario y con oportunidades de tierra y El programa de Aldeas Rurales Integradas medios de subsistencia limitados.1 (VRI, por sus siglas en francés) de Burundi Los programas de creación de aldeas se creó para satisfacer el refugio inmediato no son nuevos en esta región de África y y otras necesidades humanitarias de los han sido criticados en varias ocasiones por refugiados que ya no eran capaces de acceder el modo en el que modificaron el uso de a su tierra, no estaban seguros de la ubicación los recursos, con efectos perjudiciales en del terreno o simplemente no poseían tierra los entornos circundantes y la división del alguna. -

DE NIEBLA a EL SHOW DE TRUMAN Teresa Gómez Trueba

PERSONAJES EN BUSCA DE AUTOR Y POSMODERNIDAD: DE NIEBLA A EL SHOW DE TRUMAN Teresa Gómez Trueba UNIVERSIDAD DE VALLADOLID Resumen: En este artículo se establece una comparación entre la novela Niebla (1914), de Miguel de Unamuno, y la película El show de Truman (1998), de Peter Weir: ambas proponen un idéntico juego de confusión entre la realidad y la ficción, muy grato a la poética de la Posmodernidad, a partir de un argumento muy similar. Resumo: Neste artigo establecese unha comparación entre a novela Niebla (1914) de Miguel de Unanumo e o filme El show de Truman (1998) de Peter Weir, ambalas duas obras proponen un xogo de confusión entre realidade e ficción idéntico, moito grato á Posmodernidade, a partires dun argumento moi semellante. Abstract: The aim of this article is to establish a comparison between Miguel de Unamuno´s novel Niebla (1914) and Peter Weir´s film El Show de Truman (1998). Both of them suggest an identical game of overlapping reality and fiction having as a starting point a very similar argument, a poetic device much to the taste of Postmodernism.. Porque es cosa terrible un hombre muy convencido de su propia realidad de bulto (Miguel de Unamuno, “Una entrevista con Augusto Pérez”, publicado en La Nación, Buenos Aires, 21 de noviembre de 1915). La “realidad” nunca es otra cosa que un mundo jerárquicamente escenificado (Jean Baudrillard, Cultura y simulacro, Barcelona: Kairós, 2002, p. 35). Entre las múltiples características que la crítica ha atribuido a la ficción posmoderna, hay una muy frecuente: la puesta en entredicho del límite existente entre la propia ficción y la realidad exterior, con la consecuente invitación al lector-espectador a plantearse y cuestionar el estatuto de su propia realidad. -

Silencing Lord Haw-Haw

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History Summer 2015 Silencing Lord Haw-Haw: An Analysis of British Public Reaction to the Broadcasts, Conviction and Execution of Nazi Propagandist William Joyce Matthew Rock Cahill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Cahill, Matthew Rock, "Silencing Lord Haw-Haw: An Analysis of British Public Reaction to the Broadcasts, Conviction and Execution of Nazi Propagandist William Joyce" (2015). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 46. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/46 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Silencing Lord Haw-Haw: An Analysis of British Public Reaction to the Broadcasts, Conviction and Execution of Nazi Propagandist William Joyce By Matthew Rock Cahill HST 499: Senior Seminar Professor John L. Rector Western Oregon University June 16, 2015 Readers: Professor David Doellinger Professor Robert Reinhardt Copyright © Matthew Rock Cahill, 2015 1 On April 29, 1945 the British Fascist and expatriate William Joyce, dubbed Lord Haw-Haw by the British press, delivered his final radio propaganda broadcast in service of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany. -

By Mr Justice Edwin Cameron Supreme Court of Appeal, Bloemfontein, South Africa

The Bentam Club Presidential Address Wednesday 24 March ‘When Judges Fail Justice’ by Mr Justice Edwin Cameron Supreme Court of Appeal, Bloemfontein, South Africa 1. It is a privilege and a pleasure for me to be with you this evening. The presidency of the Bentham Club is a particular honour. Its sole duty is to deliver tonight’s lecture. In fulfilling this office I hope you will not deal with me as Hazlitt, that astute and acerbic English Romantic essayist, dealt with Bentham.1 He denounced him for writing in a ‘barbarous philosophical jargon, with all the repetitions, parentheses, formalities, uncouth nomenclature and verbiage of law-Latin’. Hazlitt, who could, as they say, ‘get on a roll’, certainly did so in his critique of Bentham, whom he accused of writing ‘a language of his own that darkens knowledge’. His final rebuke to Bentham was the most piquant: ‘His works’, he said, ‘have been translated into French – they ought to be translated into English.’ I trust that we will not tonight need the services of a translator. 2. To introduce my theme I want to take you back nearly twenty years, to 3 September 1984. The place is in South Africa – a township 60 km south of Johannesburg. It is called Sharpeville. At the time its name already had ineradicable associations with black resistance to apartheid – and with the brutality of police responses to it. On 21 March 1960, 24 years before, the police gunned down more than sixty unarmed protestors – most of them shot in the back as they fled from the scene. -

War: How Britain, Germany and the USA Used Jazz As Propaganda in World War II

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Studdert, Will (2014) Music Goes to War: How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/44008/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Music Goes to War How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II Will Studdert Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Kent 2014 Word count (including footnotes): 96,707 255 pages Abstract The thesis will demonstrate that the various uses of jazz music as propaganda in World War II were determined by an evolving relationship between Axis and Allied policies and projects. -

The Fascist Movement in Britain

Robert Benewick THE FASCIST MOVEMENT IN BRITAIN Allen Lane The Penguin Press JLE 14- Ie 1 Contents Copyright © Robert Benewick, 1969 and 1972 Preface to Revised Edition 7 First published in 1969 under the title Acknowledgements 10 Po/iJi,a/ Vio/en,e anti Pub/i, Ortler 1. II This revised edition first published in 1972 The Political Setting Allen Lane The Penguin Press 1.. Precursors 1.1. 74 Grosvenor Street, London WI 3· Portrait oja Leader 5I ISBN 0 7139 034 1 4 4. The New Party 73 Printed offset litho in Great Britain by 5. From Party to Mcvement 85 Cox & Wyman Ltd 6. Leaders and Followers 108 London, Fakenham and Reading 1.,u f'i.~, 7. British Fascist Ideology 131. G d ~ - • F. Set In Monotype aramon ~ ~~ '" .~ 8. OlYmpia 169 9· Disenchantment and Disorder 193 ~~ : 10. The East London Campaign 1.17 .,.~ \ .. ''''' lem ~ -<:.. ~~ I 1. The Public Order Act 1. 35 ~" .. , . 11.. TheDeciineojBritishFascism 263 •• (1' 13, A CiviiSociety 300 ••• Bibliograpf?y 307 Index 330 support from possible sources ofdiscontent. The most impor 7. British Fascist Ideology tant were its appeals to youth, nationalism, anti-Communism, anti-Semitism and its attacks on the political liites. Policy was often manipulated with a callous disregard for principles so that at least one of the themes, anti-Semitism, gained ascendancy over the B.O.F.'s proposals for reform. Policy was hinged to the likelihood ofan impending economic crisis and attempts were made to locate the causes and to pre scribe its resolution. As the probability ofan economic crisis _ and hence political power - grew remote, the possibility of an international crisis was stressed. -

The Appeal of Fascism to the British Aristocracy During the Inter-War Years, 1919-1939

THE APPEAL OF FASCISM TO THE BRITISH ARISTOCRACY DURING THE INTER-WAR YEARS, 1919-1939 THESIS PRESENTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OFARTS. By Kenna Toombs NORTHWEST MISSOURI STATE UNIVERSITY MARYVILLE, MISSOURI AUGUST 2013 The Appeal of Fascism 2 Running Head: THE APPEAL OF FASCISM TO THE BRITISH ARISTOCRACY DURING THE INTER-WAR YEARS, 1919-1939 The Appeal of Fascism to the British Aristocracy During the Inter-War Years, 1919-1939 Kenna Toombs Northwest Missouri State University THESIS APPROVED Date Dean of Graduate School Date The Appeal of Fascism 3 Abstract This thesis examines the reasons the British aristocracy became interested in fascism during the years between the First and Second World Wars. As a group the aristocracy faced a set of circumstances unique to their class. These circumstances created the fear of another devastating war, loss of Empire, and the spread of Bolshevism. The conclusion was determined by researching numerous books and articles. When events required sacrifice to save king and country, the aristocracy forfeited privilege and wealth to save England. The Appeal of Fascism 4 Contents Chapter One Background for Inter-War Years 5 Chapter Two The Lost Generation 1919-1932 25 Chapter Three The Promise of Fascism 1932-1936 44 Chapter Four The Decline of Fascism in Great Britain 71 Conclusion Fascism After 1940 83 The Appeal of Fascism 5 Chapter One: Background for Inter-War Years Most discussions of fascism include Italy, which gave rise to the movement; Spain, which adopted its principles; and Germany, which forever condemned it in the eyes of the world; but few include Great Britain. -

Ael/Tiecolima ALDAMA # 166 TEL

Politicos Resentidos Estan Atras de la Violencia en Mexic o COLS. 2, 3 y 4 as A LqCl- t YAMAHA MilattlietIAT ael/tieCOLIMA ALDAMA # 166 TEL. 2-34-44 Director General: Fundador: Colima, Col., Lunes 18 de Abril de 1994 Numero 13,221 Ano 41 Manuel Sanchez Silva Hector Sanchez de la Madrid Analizan la Camera Vencida de Comerciante s Exlge Ia CTM Secofl Efectua Reuniones en Busca Volver a Control de Preclos: GLR La dirigente de la Fedora- de dar Apoyo Para Ia Renegotiation cidn de Trabajadores de • Es respuesta a la solicitud planteada a Serra Puche, dijo Cardena s Colima, CTM, Graciel a Munguia • Se adeuda el 25 por ciento de los emprestitos bancarios ; no es Lanes Rivas, manifesto qua alto pero si: preocupante, afirma el dirigente de la Canaco • Canacintra s e la Secretaria de Comerci o queja de aumento en el precio del combustoleo • Afecta a industriales ; y Fomento Industrial repercutira en los consumidores, menciona Perez de la Torre • La (Setoff) debe dar march a desaceleracion economica no impacta inversiones, dice Villasenor Urib e arras a Ia liberation de pre- cios anunciada at inicio de O Semana Santa, ya qua ell o Glenda Libler MADRIGAL TRUJILL puede provocar qua el fndi- El presidente de la Camara Nacional de Colima, de los 300 millones de nuevos ce inflacionario del pals se Comercio (Canaco) Colima, Luis Fernand o pesos qua otorgd pars este sector, aproxi- acelere y que todo to gene - Cardenas Munguia, dio a conocer que l a madamente un 25 por ciento se encuentra do en estos ar os de esf uer- Secretarfa de Comercio ha iniclado un a en problema de endeudamiento. -

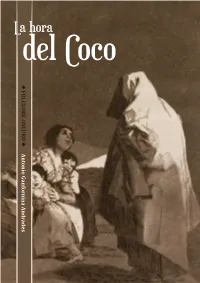

La Hora Del Coco

◆ FOLCLORE OSCURO OSCURO FOLCLORE ◆ Antonio Ganfornina Andrades Antonio del Coco La hora La La hora del Coco ◆ UN ESCENARIO DE FOLCLORE OSCURO ◆ Antonio Ganfornina Andrades Este juego fue creado para la I Edición de la Folclore Rol Jam 2020. ESCRITO Y MAQUETADO POR Antonio Ganfornina Andrades. ILUSTRACIONES Arte gratuita para uso personal y comercial extraída de Pixabay (OpenClipart-Vectors, Cliker-Free-Vector-Images y b0red). Ilustración de portada: Que viene el Coco (Francisco de Goya, 1799) DISEÑO DE LA HOJA DE PERSONAJE POR Antonio Ganfornina Andrades. AGRADECIMENTOS ESPECIALES A mi abuelo, que me arropó y cuidó del Coco, hasta que tuvo que partir a otro lugar. Reconocimiento-NoComercial-CompartirIgual - CC BY-NC-SA Esta licencia permite a otros remezclar, adaptar y construir sobre tu trabajo de forma no comercial, siempre que se reconozca la autoría y licencien sus nuevas creaciones bajo los mismos términos. ◆ FOLCLORE ROL JAM 2020 ◆ La hora del Coco ÍNDICE DE CONTENIDOS INTRODUCCIÓN 01 Lo necesario para jugar a una partida, las mecánicas y una aventura. FOLCLORE OSCURO LA HORA DEL COCO LOS PERSONAJES 07 Quiénes formarán parte de esta noche de pena y de llantos. INFANTES EN LA VIGILIA HOJAS DE PERSONAJES EL CRÍPTIDO 13 Su fuerza es su desdibujo, aquí encontrarás bocetos terribles. EL COCO: EL HORROR DESDIBUJADO VARIANTES DEL COCO INTRODUCCIÓN ◆ FOLCLORE OSCURO Es en tiempos de incertidumbre cuando recurrimos a la ficción o eso parece haber confirmado el siglo XX. Los horrores de la Primera Guerra Mundial, junto con las mejoras sanitarias que permitieron que los ejércitos volvieran a casa desfigurados en cuerpo y alma, despertaron el mismo pavor y simpatía -en igual medida- que los monstruos de los relatos. -

Britain's Green Fascists: Understanding the Relationship Between Fascism, Farming, and Ecological Concerns in Britain, 1919-1951 Alec J

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2017 Britain's Green Fascists: Understanding the Relationship between Fascism, Farming, and Ecological Concerns in Britain, 1919-1951 Alec J. Warren University of North Florida Suggested Citation Warren, Alec J., "Britain's Green Fascists: Understanding the Relationship between Fascism, Farming, and Ecological Concerns in Britain, 1919-1951" (2017). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 755. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/755 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2017 All Rights Reserved BRITAIN’S GREEN FASCISTS: Understanding the Relationship between Fascism, Farming, and Ecological Concerns in Britain, 1919-1951 by Alec Jarrell Warren A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts in History UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES August, 2017 Unpublished work © Alec Jarrell Warren This Thesis of Alec Jarrell Warren is approved: Dr. Charles Closmann Dr. Chau Kelly Dr. Yanek Mieczkowski Accepted for the Department of History: Dr. Charles Closmann Chair Accepted for the College of Arts and Sciences: Dr. George Rainbolt Dean Accepted for the University: Dr. John Kantner Dean of the Graduate School ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family, who have always loved and supported me through all the highs and lows of my journey. Without them, this work would have been impossible. -

Rompiendo El Silencio Manual De Entrenamiento Para Activistas, Consejeras Y Organizadoras Latinas

Rompiendo el Silencio Manual de Entrenamiento Para Activistas, Consejeras y Organizadoras Latinas Producido por el Fondo de Prevención de Violencia Familiar con apoyo financiero de la Oficina Contra la Violencia Hacia la Mujer, Departamento de Justicia de los EE.UU. Rompiendo el Silencio Manual de Entrenamiento Para Activistas, Consejeras y Organizadoras Latinas Autora Sonia Parras Konrad Coalición de Iowa Contra la Violencia Doméstica Editor Bernardo Merino Editora Asistente Mónica Arenas Fondo de Prevención de Violencia Familiar Directora del Proyecto Leni Marin Fondo de Prevención de Violencia Familiar Dibujante Virginia Ortega Líderes Campesinas Producido por el Fondo de Prevención de Violencia Familiar con apoyo financiero de la Oficina Contra la Violencia Hacia la Mujer, Departamento de Justicia de los EE.UU. Publicado 10/03 Dedicación A todas aquellas madres y activistas que unen sus voces hoy para romper el silencio y preparar un mundo mejor para sus hijas y otras mujeres que están por nacer en el que la violencia será un mero recuerdo del pasado. Este proyecto fue patrocinado por la Beca Número 98-MU-VX-K019 (S-1) otorgada por la Oficina Contra la Violencia Hacia la Mujer, Departamento de Justicia de los EE. UU. Los puntos de vista en el documento son los del autor y no necesariamente representan la postura oficial o las políticas del Departamento de Justicia de los EE. UU. Permiso para reproducir o adaptar el contenido de “Rompiendo el Silencio: Manual de Entrenamiento para Consejeras, Activistas y Organizadoras Latinas” El contenido de esta publicación puede ser reimpreso y adaptado con el permiso del Fondo de Prevención de Violencia Familiar.