Ocean of Reasoning: a Great Commentary on Nagarjuna's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism.Pdf

Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism Handbook of Oriental Studies Section Two South Asia Edited by Johannes Bronkhorst VOLUME 24 Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism By Johannes Bronkhorst LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bronkhorst, Johannes, 1946– Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism / By Johannes Bronkhorst. pages cm. — (Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 2, South Asia, ISSN 0169-9377 ; v. 24) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-20140-8 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—Relations— Brahmanism. 2. Brahmanism—Relations—Buddhism. 3. Buddhism—India—History. I. Title. BQ4610.B7B76 2011 294.5’31—dc22 2010052746 ISSN 0169-9377 ISBN 978 90 04 20140 8 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. CONTENTS Preface ................................................................................................ -

Annual Report 2015-16

Jeee|<ekeâ efjheesš& Annual Report 2012015555---20120120166 केb6ीय ितबती अaययन िव िवcालय Central University of Tibetan Studies (Deemed University) Sarnath, Varanasi - 221007 www.cuts.ac.in Contents Chapters Page Nos. 1. A Brief Profile of the University 3 2. Faculties and Academic Departments 10 3. Research Departments 35 4. Shantarakshita Library 55 5. Administration 64 6. Activities 75 Appendixes 1. List of Convocations held and Honoris Causa Degrees Conferred on Eminent Persons by CUTS 88 2. List of Members of the CUTS Society 90 3. List of Members of the Board of Governors 92 4. List of Members of the Academic Council 94 5. List of Members of the Finance Committee 97 6. List of Members of the Planning and Monitoring Board 98 7. List of Members of the Publication Committee 99 Editorial Committee Chairman: Dr. Banarsi Lal Associate Professor Rare Buddhist Texts Research Department Members: Dr. Mousumi Guha Banerjee Assistant Professor-in-English and Head Department of Classical and Modern Languages Dr. D. P. Singh P.A. Shantarakshita Library Member Secretary: Shri M.L. Singh Sr. Clerk (Admn. Section-I) [2] A BRIEF PROFILE OF THE UNIVERSITY 1. A BRIEF PROFILE OF THE UNIVERSITY The Central University of Tibetan Studies (CUTS) at Sarnath is one of its kind in the country. The University was established in 1967. The idea of the University was mooted in course of a dialogue between Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India and His Holiness the Dalai Lama with a view to educating the young Tibetan in exile and those from the Himalayan regions of India, who have religion, culture and language in common with Tibet. -

Tsong-Kha-Pa's Revised Presentation of Compatibly Appearing Subjects

Tsong-kha-pa’s Revised Presentation of Compatibly Appearing Subjects in The Essence of Eloquence with Jig-me-dam-chö-gya-tsho’s Commentary, 7 Jeffrey Hopkins Dual language edition of Tsong-kha-pa’s text by Jongbok Yi UMA INSTITUTE FOR TIBETAN STUDIES Tsong-kha-pa’s Revised Presentation of Compatibly Appearing Subjects Website for UMA Institute for Tibetan Studies (Union of the Modern and the Ancient: gsar rnying zung `jug khang): uma- tibet.org. UMA stands for “Union of the Modern and the Ancient” and means “Middle Way” in Tibetan. UMA is a non-profit 501(c)3 organization. Tsong-kha-pa’s Revised Presentation of Compatibly Appearing Subjects in The Essence of Eloquence with Jig-me-dam-chö-gya-tsho’s Commentary, 7 Jeffrey Hopkins Dual language edition of Tsong-kha-pa’s text by Jongbok Yi UMA Institute for Tibetan Studies uma-tibet.org UMA Great Books Translation Project Expanding Wisdom and Compassion Through Study and Contemplation Supported by generous grants from Venerable Master Bup-an and a Bequest from Daniel E. Perdue Translating texts from the heritage of Tibetan and Inner Asian Bud- dhist systems, the project focuses on Great Indian Books and Ti- betan commentaries from the Go-mang College syllabus as well as a related theme on the fundamental innate mind of clear light in Tantric traditions. A feature of the Project is the usage of consistent vocabulary and format throughout the translations. Publications are available online without cost under a Creative Commons License with the understanding that downloaded material must be distributed for free: http://uma-tibet.org. -

REPORT Part - C Vol

Visva-Bharati Santiniketan 731235 INDIA SELF-STUDY REPORT Part - C Vol. 2 Evaluative Report of the Departments Submitted to National Assessment and Accreditation Council 2014 C O N T E N T S VIDYA-BHAVANA ( INSTITUTE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES ) Economics and Politics 1 Philosophy and Religion 39 Ancient Indian History, Culture & Archaeology (A.I.H.C. & A.) 61 Journalism and Mass Communication 71 Geography 89 Anthropology 103 History 113 BHASHA-BHAVANA ( INSTITUTE OF LANGUAGE, LITERATURE AND CULTURE ) Bengali 130 English and Other Modern European Languages (DEOMEL) 151 Sanskrit, Pali & Prakrit 196 Hindi 213 Chinese Language & Culture 236 Japanese 253 Indo-Tibetan Studies 266 Odia 281 Santali 297 Arabic, Persian, Urdu & Islamic Studies 308 Assamese 318 Marathi 326 Tamil 334 PALLI SAMGATHANA VIBHAGA ( INSTITUTE OF RURAL RECONSTRUCTION ) Palli Charcha Kendra 342 Lifelong Learning and Extension 357 Silpa Sadana 376 Social Work 401 Women's Studies Centre 431 Evaluative Report of the Department of Economics and Politics, Vidya-Bhavana 1 Evaluative Report of the Department of Economics and Politics 1. Name of the Department : Department of Economics and Politics 2. Year of establishment : 1953 3. Is the Department part of a School/Faculty of the university? Yes, Vidya-Bhavana 4. Names of programmes offered (UG, PG, M.Phil., Ph.D., integrated Masters; Integrated Ph.D., D.Sc., D.Litt., etc.) : a) Ph. D in Economics b) Ph D in Political science c) M Phil in Economics d) MA in Economics e) BA(Hons) in Economics f) BA (subsidiary/ allied) in Economics g) BA (subsidiary/ allied) in Political Science h) BA (subsidiary/ allied) in Integrated Mathematics & Statistics 5. -

Annual Report 2013-14

केन्द्रीय ति녍बिी अध्ययन तिश्वतिद्यालय Central University of Tibetan Studies (Deemed University) Jeee|<ekeâ efjheesš& Annual Report 2013-2014 SARNATH, VARANASI - 221007 www.cuts.ac.in Contents Chapters Page Nos. 1. A Brief Profile of the University 3 2. Faculties and Academic Departments 10 3. Research Departments 29 4. Shantarakshita Library 49 5. Administration 57 6. Activities 63 Appendixes 1. List of Convocations held and Honoris Causa Degrees Conferred on Eminent Persons by CUTS 78 2. List of Members of the CUTS Society 80 3. List of Members of the Board of Governors 82 4. List of Members of the Academic Council 84 5. List of Members of the Finance Committee 87 6. List of Members of the Planning and Monitoring Board 88 7. List of Members of the Publication Committee 89 Editorial Committee Chairman: Dr. Banarsi Lal Associate Professor Rare Buddhist Texts Research Department Members: Mousumi Guha Banerjee Assistant Professor-in-English and Head Department of Classical and Modern Languages Dr. D. P. Singh P.A. Shantarakshita Library Member Secretary: Shri M.L. Singh Sr. Clerk (Admn. Section-I) [2] A BRIEF PROFILE OF THE UNIVERSITY 1. A BRIEF PROFILE OF THE UNIVERSITY The Central University of Tibetan Studies (CUTS) at Sarnath is one of its kind in the country. The University was established in 1967. The idea of the University was mooted in course of a dialogue between Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of India and His Holiness the Dalai Lama with a view to educating the young Tibetan diaspora and those from the Himalayan border regions of India, who have religion, culture and language in common with Tibet. -

Participants 29 Conference

PARTICIPANTS 29 CONFERENCE PARTICIPANTS ACADEMIC CONVENORS PROF . GESHE NGAWANG SAMTEN (b. 1956) is presently the Vice Chancellor of Central University of Tibetan Studies, Sarnath, Varanasi, and has been Professor of Indian Buddhist Philosophy at the University before assuming the high office. He is educated both in the modern system as well as in the Buddhist and Tibetan Studies in the monastic mode. He has such important publications to his credit, as a definitive critical edition of Ratnavali with commentary, Abhidhammathasamgaho ; Sanskrit and Tibetan versions of the Pindikrita and the Pancakrama of Nagarjuna; Manjusri , an illustrated monograph on Tibetan Buddhist scroll paintings, and co-authored The Ocean of Reasoning , (Oxford University Press, New York) an annotated English translation of the commentary on Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamaka Karika by the Tibetan master- philosopher Tson-Kha-Pa. And scores of papers in various learned anthologies published in India and abroad. He has been Visiting Professor in various Universities and colleges in USA and Australia. He has also been instrumental in promoting Buddhist Studies in India. Various Indian Universities have sought his guidance and advice in the matter of formulating their syllabi of Buddhist philosophy and researches. He is on numerous academic bodies, Universities and expert committees of the Ministries of the Government of India. In 2008, he was decorated with Padma Shri by the President of India in recognition of his distinguished services in the fields of education and literature. GESHE DORJI DAMDUL did his schooling in TCV School, Dharamsala with main interest in Physics and Mathematics. In 1988, soon after his high school in Science stream, he joined the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics, Dharamsala for formal studies in Buddhist logic, philosophy and epistemology. -

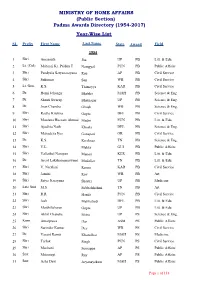

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List SL Prefix First Name Last Name State Award Field 1954 1 Shri Amarnath Jha UP PB Litt. & Edu. 2 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PUN PB Public Affairs 3 Shri Pandyala Satyanarayana Rau AP PB Civil Service 4 Shri Sukumar Sen WB PB Civil Service 5 Lt. Gen. K.S. Thimayya KAR PB Civil Service 6 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha MAH PB Science & Eng. 7 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar UP PB Science & Eng. 8 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh WB PB Science & Eng. 9 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta DEL PB Civil Service 10 Shri Moulana Hussain Ahmad Madni PUN PB Litt. & Edu. 11 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla DEL PB Science & Eng. 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati OR PB Civil Service 13 Dr. K.S. Krishnan TN PB Science & Eng. 14 Shri V.L. Mehta GUJ PB Public Affairs 15 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon KER PB Litt. & Edu. 16 Dr. Arcot Lakshamanaswami Mudaliar TN PB Litt. & Edu. 17 Shri V. Narahari Raooo KAR PB Civil Service 18 Shri Jamini Roy WB PB Art 19 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri UP PB Medicine 20 Late Smt. M.S. Subbalakshmi TN PB Art 21 Shri R.R. Handa PUN PB Civil Service 22 Shri Josh Malihabadi DEL PB Litt. & Edu. 23 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta UP PB Litt. & Edu. 24 Shri Akhil Chandra Mitra UP PS Science & Eng. 25 Kum. Amalprava Das ASM PS Public Affairs 26 Shri Surinder Kumar Dey WB PS Civil Service 27 Dr. Vasant Ramji Khanolkar MAH PS Medicine 28 Shri Tarlok Singh PUN PS Civil Service 29 Shri Machani Somappa AP PS Public Affairs 30 Smt. -

Compatibly Appearing Subjects, 8

Exposing Bhāvaviveka’s Assertion of Inherent Existence: 2nd Dalai Lama Gen-dün-gya-tsho, Je-drung She-rab-wang-po, Zha-mar Ge-dün-tan-dzin-gya-tsho, Jig-me-dam-chö-gya-tsho, and Khay-drub Ge-leg-pal-sang: Compatibly Appearing Subjects, 8 Jeffrey Hopkins UMA INSTITUTE FOR TIBETAN STUDIES Exposing Bhāvaviveka’s Assertion of Inherent Existence Website for UMA Institute for Tibetan Studies (Union of the Modern and the Ancient: gsar rnying zung `jug khang): uma- tibet.org. UMA stands for “Union of the Modern and the Ancient” and means “Middle Way” in Tibetan. UMA is a non-profit 501(c)3 organization. Exposing Bhāvaviveka’s Assertion of Inherent Existence: 2nd Dalai Lama Gen-dün-gya-tsho, Je-drung She-rab-wang-po, Zha-mar Ge-dün-tan-dzin-gya-tsho, Jig-me-dam-chö-gya-tsho, and Khay-drub Ge-leg-pal-sang: Compatibly Appearing Subjects, 8 Jeffrey Hopkins UMA Institute for Tibetan Studies uma-tibet.org UMA Great Books Translation Project Expanding Wisdom and Compassion Through Study and Contemplation Supported by generous grants from Venerable Master Bup-an and a Bequest from Daniel E. Perdue Translating texts from the heritage of Tibetan and Inner Asian Bud- dhist systems, the project focuses on Great Indian Books and Ti- betan commentaries from the Go-mang College syllabus as well as a related theme on the fundamental innate mind of clear light in Tantric traditions. A feature of the Project is the usage of consistent vocabulary and format throughout the translations. Publications are available online without cost under a Creative Commons License with the understanding that downloaded material must be distributed for free: http://uma-tibet.org. -

Chapter One Introduction

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction The Wheel of Life (Bhavacakra) is a Buddhist teaching through art. The Wheel of Life depicts the basic teachings of the Buddha i.e. the Four Noble Truth, Karma and Cause and Effect (Dependent Origination) skillfully. So, the Wheel of Life (Bhavacakra) is philosophically based on the first teaching of the Buddha. The Wheel of Life (Bhavacakra) is one of the most striking and important illustrations of Buddha’s teachings, capturing the key elements of rebirth, karma, and dependent origination. It is one of the most popular iconographies in Northern Buddhism. The Wheel of Life is called ‘Bhavacakra’, ‘Bhavacakka’ and srid pa'i 'khor lo’ respectively in Saṃskrit, Pali and Tibetan languages. The Wheel of Life is a metaphysical diagram depicting the various realms of cyclic existence and the beings inhabiting these realms. It is primarily a visual aid to help us gain a clear understanding of the workings of human mind. It is a symbolic representation of saṃsāra found on the outside walls of Northern Buddhist dGonpas (monasteries). The Bhavacakra is popularly referred to as the Wheel of Life, and may also be glossed as wheel of cyclic existence or wheel of becoming or wheel of rebirth or wheel of saṃsāra or wheel of suffering or wheel of transformation. The Wheel of Life can be read by all including illiterate persons. It should not need esoteric knowledge. In other words, no esoteric knowledge is needed to understand the Wheel of Life. The Wheel of Life is a real picture of Pratityasamudpada or Doctrine of Dependent Origination. -

To Be Uploaded on Dhc Website

RESULT OF DELHI JUDICIAL SERVICE PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION ‐ 2014 HELD ON 01.06.2014 Total marks DJSE S NO ROLL NO. NAME FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME CATEGORY obtained out FORM NO. of 200 marks 1 416966 101140002 SATISH KUMAR HARI CHAND SC (PH Ortho) 94.75 2 411549 101140003 RAJENDER PRASHAD SUKRI LAL SC (PH Ortho) 37.00 3 419731 101140004 INDRAPAL SINGH ONKAR SINGH GENERAL 34.75 4 416965 101140005 ASHOK KUMAR SH RAM CHAND SC (PH B/LV) 71.25 5 417227 101140006 SUNIL KUMAR TARA CHAND GENERAL 131.00 6 416596 101140007 ARUN BANSAL B M BANSAL GENERAL (PH Ortho) 102.25 7 416859 101140009 RAMESHWAR DAYAL MEENA BHORE LAL MEENA ST (PH B/LV) 55.25 8 416405 101140010 SOMDATT SHARMA RAMJILAL SHARMA GENERAL (PH Ortho) 64.75 9 416956 101140011 RAKESH KUMAR HARBIR SC (PH Ortho) 51.50 10 412004 101140012 RAKESH KUMAR KHEM CHAND SHARMA GENERAL (PH Ortho) 48.25 11 416955 101140013 RAJWANT KAUR MEWA SINGH SC (PH Ortho) 103.75 12 416954 101140014 SUNIL KUMAR TEK RAM SC (PH Ortho) 19.00 13 413908 101140016 VISHAL KUMAR GUPTA A K GUPTA GENERAL (PH Ortho) 75.50 14 416962 101140017 SUNIL KUMAR SUNDER LAL SC (PH Ortho) 64.50 15 416961 101140018 MANOJ KUMAR CHANDER DEV GENERAL (PH Ortho) 112.75 16 417862 101140019 KSHITIJ KUMAR SURJAN SINGH GENERAL 98.25 17 416963 101140021 RAJ KUMAR PRITHVI RAJ SC (PH Ortho) 49.50 18 412957 101140022 HARISH KUMAR RATTAN SINGH SC (PH Ortho) 53.50 19 412305 101140023 OM NARAYAN YADAV TIKA RAM YADAV GENERAL (PH Ortho) 36.50 20 412954 101140024 JAIPAL SINGH PARAS RAM SC 47.75 21 416726 101140025 BHAGCHAND BAIRWA RAM NIWAS SC 7.50 22 416794 -

Annual Report 2015-16

Annual Report 2015-16 Ministry of Culture Government of India Contents Contents Contents 1. Ministry of Culture - An Overview 1 2. Tangible Cultural Heritage 2.1 Archaeological Survey of India 5 2.2 Museums 27 2.2a National Museum 27 2.2b National Gallery of Modern Art 36 2.2c Indian Museum 50 2.2d Victoria Memorial Hall 52 2.2e Salar Jung Museum 54 2.2f Allahabad Museum 59 2.2g National Council of Science Museum 62 2.3 Capacity Building in Museum related activities 64 2.3a National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology 64 2.3b National Research Laboratory for conservation of Cultural Property 66 2.4 National Culture Fund (NCF) 67 2.5 International Cultural Relations (ICR) 69 2.6 UNESCO Matters 71 2.7 National Monuments Authority 73 2.8 National Missions 75 2.8a National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities 75 2.8b National Mission for Manuscripts 75 2.8c National Mission on Libraries 78 2.8d National Mission on Gandhi Heritage Sites 79 3. Intangible Cultural Heritage 3.1 National School of Drama 83 3.2 Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts 87 3.3 Akademies 94 3.3a Sahitya Akademi 94 3.3b Lalit Kala Akademi 98 3.3c Sangeet Natak Akademi 104 iv Contents 3.4 Centre for Cultural Resources and Training 109 3.5 Kalakshetra Foundation 114 3.6 Zonal cultural Centres 118 3.6a North Zone Cultural Centre 118 3.6b Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre 122 3.6c South Zone Cultural Centre 124 3.6d West Zone Cultural Centre 126 3.6e South Central Zone Cultural Centre 128 3.6f North Central Zone Cultural Centre 129 3.6g North East Zone Cultural Centre 132 4. -

PMR Transaction Offer - Winner List – May 2019

PMR transaction offer - Winner list – May 2019 Full Name KULDEEP KUMAR BRIJESH MUKUND MISTRY JUDE GUEDES JT1 ASHISH GUPTA ASHISHKUMAR K JOSHI SHAHNAZ S DINESH SINGH DEVIDAS KALUJI MAHALE RAVINDRAKUMAR BALMIKI RAHUL CHOWDHURY UMESHBHAI K VAZA SINI U N CHANDRASHEKHAR IYER TALHA SHAMEER SHAIKH ROY INDRANIL PRADIP PRADNYA POLEKAR SHRIKANT SUBHASH WAKALE SYED SHAKEER PRINCE MATHEW SHANTARAM PANDHARINATH THAKARE SARANG BHAUSAHEB SALOKHE ANANT SHAHADEV PAWAR PRABHLEEN KAUR RISHI MEHROTRA K VISWANATHA REDDY ABHISHEK MANDAL PRASHANT TANAJI ATHAWALE SAURABH SONAWANE RAHUL MANOHAR KORAWAR RAJESH SAHADEO NAME JASHOBANTA BEHERA SANJAY SHANKAR PAVASKAR (JT) SAYED KHIZAR ALI SAYED SHOUKAT ALI RAMESH SAKHARAM TATHE UMASANKAR ROUTARAY ANMOL HEMANT KUMAR RAY RAMESH KUMAR TIWARI SHOBHNATH SHARMA VIVEK KUMAR CHAUBE SAMAR BIJAYEE MOHANTY RAHUL GAUR ASHU KUMAR DATTAGURU CHARI SANTHOSHA J ANUPAMA GANGAPPA NAGAVI ABHINABA SADHU RAJASEKAR S ANIL VERMA ABDUS SAEED ABDUL RASHID SHAIKH MOHAMMAD SHAKIR MOHAMMAD YAQUB SUNIL RAMCHANDRA MUNDPHANE SANDEEP KUMAR BISWA RANJAN SARANGI VISHNU S PRAMOD SINGH MANIKANDAN R SWATHI KOLE BENTU SINGH MANISH KUMAR FARHANA SHAIKH SWETHA R DHANASHRI MHATRE DWIPAN BHATTACHARJEE NILESHBHAI PREMJIBHAI MANGUKIYA ANUPRIYA SATISH ZARKAR GAURAVKUMAR B PATEL SIDDHESH SUBHASH MAHADIK ABOO NADAL ARAJ S RAHUL RUDANI MD OMAR FARUK MOLLA (MINOR) HARISHA VASUDEV PARMAR B KRUPAKAR BODRUL ISLAM RASHMI MAUNIK VEKARIYA JT1 VIJAY BAHADUR SINGH JT1 SYED ASIM ABBAS LINIMARY R VAIBHAV JAIN DHARMENDRA KUMAR JAYANTH C PODIMATTAM SANJAY YADAV AMARSINGH AMIT KUMAR MITRA GOKUL G RAHUL CHOUDHARY NEERAJ CHAMOLI ANKIT SHARMA ADARSH JHAVERI MATEEN AHMAD SIDDIQUI EQBAL ASSADI NARESH KUMAR DHIMAN NATESH KHARVI SNEHAL CHIRAG VIRA SANJAY SINGH SACHIN CHOUHAN MAKWANA JABIRBHAI KALUBHAI T DEENADHAYALAN MOHAMMADFAIJAN TURKI ABHISHEK KUMAR SINGH AMER SALEEM ANURODH KUMAR SWAGATIKA SAHOO BRIJESH TIWARI P DEVENDER REDDY MAYURI GANGULY PANKAJ RABINDRA RAUT SYEDA NAUSHEEN FATIMA BHARGAV BAROT AYESHA SIDDEQUA VISHAL VIKAS KANSE SANJAY KUMAR .