Buddhism in the Shadow of Brahmanism.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Banārasīdās Dans L'histoire De La Pensée

De la convention à la conviction : Banārasīdās dans l’histoire de la pensée digambara sur l’absolu Jérôme Petit To cite this version: Jérôme Petit. De la convention à la conviction : Banārasīdās dans l’histoire de la pensée digambara sur l’absolu. Religions. Université Paris 3 Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2013. Français. tel-01112799 HAL Id: tel-01112799 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01112799 Submitted on 3 Feb 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE SORBONNE NOUVELLE - PARIS 3 ED 268 Langage et langues : description, théorisation, transmission UMR 7528 Mondes iranien et indien Thèse de doctorat Langues, civilisations et sociétés orientales (études indiennes) Jérôme PETIT DE LA CONVENTION À LA CONVICTION BAN ĀRAS ĪDĀS DANS L’HISTOIRE DE LA PENSÉE DIGAMBARA SUR L’ABSOLU Thèse dirigée par Nalini BALBIR Soutenue le 20 juin 2013 JURY : M. François CHENET, professeur, Université Paris-Sorbonne M. John CORT, professeur, Denison University, États-Unis M. Nicolas DEJENNE, maître de conférences, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle Mme. Françoise DELVOYE, directeur d’études, EPHE, Section des Sciences historiques et philologiques Résumé L’œuvre de Ban āras īdās (1586-1643), marchand et poète jaina actif dans la région d’Agra, s’appuie e sur la pensée du maître digambara Kundakunda (c. -

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Prabhakar Machwe Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Dr. Prabhakar Machwe (1917-1991) Prolific writer, linguist and an authority on Indian literature, Dr. Prabhakar Machwe was born on 26 December 1917 at Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India. He graduated from Vikram University, Ujjain and obtained Masters in Philosophy, 1937, and English Literature, 1945, Agra University; Sahitya Ratna and Ph.D, Agra University, 1957. Dr. Machwe started his career as a lecturer in Madhav College, Ujjain, 1938-48. He worked as Literary Producer, All India Radio, Nagpur, Allahabad and New Delhi, 1948-54. He was closely associated with Sahitya Akademi from its inception in 1954 and served as Assistant Secretary, 1954-70, and Secretary, 1970-75. Dr. Machwe was Visiting Professor in Indian Studies Departments at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California on a Fulbright and Rockefeller grant (1959-1961); and later Officer on Special Duty (Language) in Union Public Service Commission, 1964-66. After retiring from Sahitya Akademi in 1975, Dr. Machwe was a visiting fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Simla, 1976-77, and Director of Bharatiya Bhasha Parishad, Calcutta, 1979-85. He spent the last years of his life in Indore as Chief Editor of a Hindi daily, Choutha Sansar, 1988-91. Dr. Prabhakar Machwe travelled widely for lecture tours to Germany, Russia, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Japan and Thailand. He organised national and international seminars on the occasion of the birth centenaries of Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo between 1961 and 1972. -

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Vaishvanara Vidya.Pdf

VVAAIISSHHVVAANNAARRAA VVIIDDYYAA by Swami Krishnananda The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India (Internet Edition: For free distribution only) Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS Publishers’ Note 3 I. The Panchagni Vidya 4 The Course Of The Soul After Death 5 II. Vaishvanara, The Universal Self 26 The Heaven As The Head Of The Universal Self 28 The Sun As The Eye Of The Universal Self 29 Air As The Breath Of The Universal Self 30 Space As The Body Of The Universal Self 30 Water As The Lower Belly Of The Universal Self 31 The Earth As The Feet Of The Universal Self 31 III. The Self As The Universal Whole 32 Prana 35 Vyana 35 Apana 36 Samana 36 Udana 36 The Need For Knowledge Is Stressed 37 IV. Conclusion 39 Vaishvanara Vidya Vidya by by Swami Swami Krishnananda Krishnananda 21 PUBLISHERS’ NOTE The Vaishvanara Vidya is the famous doctrine of the Cosmic Meditation described in the Fifth Chapter of the Chhandogya Upanishad. It is proceeded by an enunciation of another process of meditation known as the Panchagni Vidya. Though the two sections form independent themes and one can be studied and practised without reference to the other, it is in fact held by exponents of the Upanishads that the Vaishvanara Vidya is the panacea prescribed for the ills of life consequent upon the transmigratory process to which individuals are subject, a theme which is the central point that issues from a consideration of the Panchagni Vidya. This work consists of the lectures delivered by the author on this subject, and herein are reproduced these expositions dilating upon the two doctrines mentioned. -

Gandharan Origin of the Amida Buddha Image

Ancient Punjab – Volume 4, 2016-2017 1 GANDHARAN ORIGIN OF THE AMIDA BUDDHA IMAGE Katsumi Tanabe ABSTRACT The most famous Buddha of Mahāyāna Pure Land Buddhism is the Amida (Amitabha/Amitayus) Buddha that has been worshipped as great savior Buddha especially by Japanese Pure Land Buddhists (Jyodoshu and Jyodoshinshu schools). Quite different from other Mahāyāna celestial and non-historical Buddhas, the Amida Buddha has exceptionally two names or epithets: Amitābha alias Amitāyus. Amitābha means in Sanskrit ‘Infinite light’ while Amitāyus ‘Infinite life’. One of the problems concerning the Amida Buddha is why only this Buddha has two names or epithets. This anomaly is, as we shall see below, very important for solving the origin of the Amida Buddha. Keywords: Amida, Śākyamuni, Buddha, Mahāyāna, Buddhist, Gandhara, In Japan there remain many old paintings of the Amida Triad or Trinity: the Amida Buddha flanked by the two bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Mahāsthāmaprāpta (Fig.1). The function of Avalokiteśvara is compassion while that of Mahāsthāmaprāpta is wisdom. Both of them help the Amida Buddha to save the lives of sentient beings. Therefore, most of such paintings as the Amida Triad feature their visiting a dying Buddhist and attempting to carry the soul of the dead to the AmidaParadise (Sukhāvatī) (cf. Tangut paintings of 12-13 centuries CE from Khara-khoto, The State Hermitage Museum 2008: 324-327, pls. 221-224). Thus, the Amida Buddha and the two regular attendant bodhisattvas became quite popular among Japanese Buddhists and paintings. However, the origin of this Triad and also the Amida Buddha himself is not clarified as yet in spite of many previous studies dedicated to the Amida Buddha, the Amida Triad, and the two regular attendant bodhisattvas (Higuchi 1950; Huntington 1980; Brough 1982; Quagliotti 1996; Salomon/Schopen 2002; Harrison/Lutczanits 2012; Miyaji 2008; Rhi 2003, 2006). -

1-15 a SHORT HISTORY of JAINA LAW1 Peter Flügel the Nine

International Journal of Jaina Studies (Online) Vol. 3, No. 4 (2007) 1-15 A SHORT HISTORY OF JAINA LAW1 Peter Flügel The nineteenth century English neologism ‘Jaina law’ is a product of colonial legal intervention in India from 1772 onwards. 'Jaina law' suggests uniformity where in reality there is a plurality of scriptures, ethical and legal codes, and customs of sect, caste, family and region. The contested semantics of the term reflect alternative attempts by the agents of the modern Indian legal system and by Jain reformers to restate traditional Jain concepts. Four interpretations of the modern term 'Jaina law' can be distinguished: (i) 'Jaina law' in the widest sense signifies the doctrine and practice of jaina dharma, or Jaina ‘religion’. (ii) In a more specific sense it points to the totality of conventions (vyavahāra) and law codes (vyavasthā) in Jaina monastic and lay traditions.2 Sanskrit vyavasthā and its Arabic and Urdu equivalent qānūn both designate a specific code of law or legal opinion/decision, whereas Sanskrit dharma can mean religion, morality, custom and law. (iii) The modern Indian legal system is primarily concerned with the 'personal law' of the Jaina laity. In Anglo-Indian case law, the term 'Jaina law' was used both as a designation for 'Jain scriptures' (śāstra) on personal law, and for the unwritten 'customary laws' of the Jains, that is the social norms of Jain castes (jāti) and clans (gotra). (iv) In 1955/6 Jaina personal law was submerged under the statutory 'Hindu Code', and is now only indirectly recognised by the legal system in the form of residual Jain 'customs' to be proved in court. -

Indian Hieroglyphs

Indian hieroglyphs Indus script corpora, archaeo-metallurgy and Meluhha (Mleccha) Jules Bloch’s work on formation of the Marathi language (Bloch, Jules. 2008, Formation of the Marathi Language. (Reprint, Translation from French), New Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN: 978-8120823228) has to be expanded further to provide for a study of evolution and formation of Indian languages in the Indian language union (sprachbund). The paper analyses the stages in the evolution of early writing systems which began with the evolution of counting in the ancient Near East. Providing an example from the Indian Hieroglyphs used in Indus Script as a writing system, a stage anterior to the stage of syllabic representation of sounds of a language, is identified. Unique geometric shapes required for tokens to categorize objects became too large to handle to abstract hundreds of categories of goods and metallurgical processes during the production of bronze-age goods. In such a situation, it became necessary to use glyphs which could distinctly identify, orthographically, specific descriptions of or cataloging of ores, alloys, and metallurgical processes. About 3500 BCE, Indus script as a writing system was developed to use hieroglyphs to represent the ‘spoken words’ identifying each of the goods and processes. A rebus method of representing similar sounding words of the lingua franca of the artisans was used in Indus script. This method is recognized and consistently applied for the lingua franca of the Indian sprachbund. That the ancient languages of India, constituted a sprachbund (or language union) is now recognized by many linguists. The sprachbund area is proximate to the area where most of the Indus script inscriptions were discovered, as documented in the corpora. -

Avalokiteśvara and Brahmā's Entreaty

Avalokiteśvara and Brahmā’s Entreaty Akira Saito Preamble As is well known, Avalokiteśvara is a bodhisattva representative of Mahāyāna Buddhism, and beliefs in Avalokiteśvara have flourished wherever Buddhism, especially Mahāyāna Buddhism, spread in Asia. Partly because the characteristic of assuming various forms to save people in distress was attributed to Avalokiteśvara, there evolved six, seven, and thirty-three forms of Avalokiteśvara, who also amalgamated with earth goddesses such as Niangniang 娘娘, and in Japan pilgrimages to sites sacred to Avalokiteśvara have been long established among the general populace, typical of which is the pilgrimage to thirty-three temples in the Kansai region (Saigoku sanjūsansho 西國三十三所). There exists much prior research on Avalokiteśvara, who was accepted in various forms in many regions to which Buddhism spread, and on his iconography, concrete representation, and cult. But on the other hand it is also true that there remains much that is puzzling about the name “Avalokiteśvara” and its meaning, origins, and background. In the following, having first provided a critical overview of recent relevant research, I wish to reconsider the meaning and background of his original name (avalokita-īśvara, -svara, -smara, etc.) in relation to the story of Brahmā’s entreaty, a perspective that has been largely missing in past research. 1. Recent Research on Avalokiteśvara’s Original Name Among studies of Avalokiteśvara in recent years, worthy of particular note are those by Tanaka (2010),1 who discusses in detail -

Indian Philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article

Indian philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article Indian philosophy the systems of thought and reflection that were developed by the civilizations of the Indian subcontinent. They include both orthodox (astika) systems, namely, the Nyaya, Vaisesika, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva-mimamsa, and Vedanta schools of philosophy, and unorthodox (nastika) systems, such as Buddhism and Jainism. Indian thought has been concerned with various philosophical problems, significant among them the nature of the world (cosmology), the nature of reality (metaphysics), logic, the nature of knowledge (epistemology), ethics, and religion. General considerations Significance of Indian philosophies in the history of philosophy In relation to Western philosophical thought, Indian philosophy offers both surprising points of affinity and illuminating differences. The differences highlight certain fundamentally new questions that the Indian philosophers asked. The similarities reveal that, even when philosophers in India and the West were grappling with the same problems and sometimes even suggesting similar theories, Indian thinkers were advancing novel formulations and argumentations. Problems that the Indian philosophers raised for consideration, but that their Western counterparts never did, include such matters as the origin (utpatti) and apprehension (jñapti) of truth (pramanya). Problems that the Indian philosophers for the most part ignored but that helped shape Western philosophy include the question of whether knowledge arises from experience or from reason and distinctions such as that between analytic and synthetic judgments or between contingent and necessary truths. Indian thought, therefore, provides the historian of Western philosophy with a point of view that may supplement that gained from Western thought. A study of Indian thought, then, reveals certain inadequacies of Western philosophical thought and makes clear that some concepts and distinctions may not be as inevitable as they may otherwise seem. -

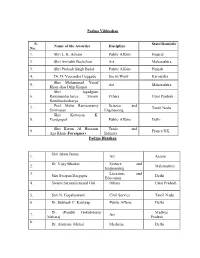

Padma Vibhushan S. No. Name of the Awardee Discipline State/Domicile

Padma Vibhushan S. State/Domicile Name of the Awardee Discipline No. 1. Shri L. K. Advani Public Affairs Gujarat 2. Shri Amitabh Bachchan Art Maharashtra 3. Shri Prakash Singh Badal Public Affairs Punjab 4. Dr. D. Veerendra Heggade Social Work Karnataka Shri Mohammad Yusuf 5. Art Maharashtra Khan alias Dilip Kumar Shri Jagadguru 6. Ramanandacharya Swami Others Uttar Pradesh Rambhadracharya Prof. Malur Ramaswamy Science and 7. Tamil Nadu Srinivasan Engineering Shri Kottayan K. 8. Venugopal Public Affairs Delhi Shri Karim Al Hussaini Trade and 9. France/UK Aga Khan ( Foreigner) Industry Padma Bhushan Shri Jahnu Barua 1. Art Assam Dr. Vijay Bhatkar Science and 2. Maharashtra Engineering 3. Literature and Shri Swapan Dasgupta Delhi Education 4. Swami Satyamitranand Giri Others Uttar Pradesh 5. Shri N. Gopalaswami Civil Service Tamil Nadu 6. Dr. Subhash C. Kashyap Public Affairs Delhi Dr. (Pandit) Gokulotsavji Madhya 7. Art Maharaj Pradesh 8. Dr. Ambrish Mithal Medicine Delhi 9. Smt. Sudha Ragunathan Art Tamil Nadu 10. Shri Harish Salve Public Affairs Delhi 11. Dr. Ashok Seth Medicine Delhi 12. Literature and Shri Rajat Sharma Delhi Education 13. Shri Satpal Sports Delhi 14. Shri Shivakumara Swami Others Karnataka Science and 15. Dr. Kharag Singh Valdiya Karnataka Engineering Prof. Manjul Bhargava Science and 16. USA (NRI/PIO) Engineering 17. Shri David Frawley Others USA (Vamadeva) (Foreigner) 18. Shri Bill Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 19. Ms. Melinda Gates Social Work USA (Foreigner) 20. Shri Saichiro Misumi Others Japan (Foreigner) Padma Shri 1. Dr. Manjula Anagani Medicine Telangana Science and 2. Shri S. Arunan Karnataka Engineering 3. Ms. Kanyakumari Avasarala Art Tamil Nadu Literature and Jammu and 4. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita