Chapter One Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism Dukkha Samudaya Nirodha Magga Key Vocabulary the Buddha

Buddhism Key Vocabulary The Buddha Buddhists live by five rules: There are no gods in • Never take the life of The teacher and Buddhism. It was created Buddha a living creature. creator of Buddhism. by a man called Siddhartha Gautama, who was born • Do not steal. into a noble family. He lived When Buddhists • Be faithful to your partner. a sheltered early life, but close their eyes and when he was older he went • Do not lie. Meditate breathe deeply, trying out into the world and saw to empty their minds • Do not drink alcohol. that sickness, age and death of thoughts. come to everyone. After seeing Buddhism originated Breaking the Buddhist this, Gautama meditated and in Northeast India and Enlightenment cycle of rebirth and found the answer to life. This now has followers from reaching Nirvana. made him the Buddha. This was called enlightenment all over the world. The The rules laid out by and the Buddha decided to Dharmachakra is a Eightfold Buddha which will teach others how to reach it. symbol used in Buddhism. Path lead to Nirvana. Dukkha Samudaya Nirodha Magga ‘The Wheel Dharmachakra Everyone The cause of To end the suffering, To end the suffering of Dharma’. suffers in life. suffering is a life must be lived for good, people craving for things one day at a time. must follow the Perfect peace with no and wanting to You must also let go Eightfold Path Nirvana suffering. control things. of cravings. created by Buddha. View more Buddhism planning resources. visit twinkl.com Buddhism Key Vocabulary Special Shrines Buddhists can worship from home or at a temple, which are puja The Buddhist act of worship. -

The Meaning of “Zen”

MATSUMOTO SHIRÕ The Meaning of “Zen” MATSUMOTO Shirõ N THIS ESSAY I WOULD like to offer a brief explanation of my views concerning the meaning of “Zen.” The expression “Zen thought” is not used very widely among Buddhist scholars in Japan, but for Imy purposes here I would like to adopt it with the broad meaning of “a way of thinking that emphasizes the importance or centrality of zen prac- tice.”1 The development of “Ch’an” schools in China is the most obvious example of how much a part of the history of Buddhism this way of think- ing has been. But just what is this “zen” around which such a long tradition of thought has revolved? Etymologically, the Chinese character ch’an 7 (Jpn., zen) is thought to be the transliteration of the Sanskrit jh„na or jh„n, a colloquial form of the term dhy„na.2 The Chinese characters Ï (³xed concentration) and ÂR (quiet deliberation) were also used to translate this term. Buddhist scholars in Japan most often used the com- pound 7Ï (zenjõ), a combination of transliteration and translation. Here I will stick with the simpler, more direct transliteration “zen” and the original Sanskrit term dhy„na itself. Dhy„na and the synonymous sam„dhi (concentration), are terms that have been used in India since ancient times. It is well known that the terms dhy„na and sam„hita (entering sam„dhi) appear already in Upani- ¤adic texts that predate the origins of Buddhism.3 The substantive dhy„na derives from the verbal root dhyai, and originally meant deliberation, mature reµection, deep thinking, or meditation. -

Early Buddhist Concepts in Today's Language

1 Early Buddhist Concepts In today's language Roberto Thomas Arruda, 2021 (+55) 11 98381 3956 [email protected] ISBN 9798733012339 2 Index I present 3 Why this text? 5 The Three Jewels 16 The First Jewel (The teachings) 17 The Four Noble Truths 57 The Context and Structure of the 59 Teachings The second Jewel (The Dharma) 62 The Eightfold path 64 The third jewel(The Sangha) 69 The Practices 75 The Karma 86 The Hierarchy of Beings 92 Samsara, the Wheel of Life 101 Buddhism and Religion 111 Ethics 116 The Kalinga Carnage and the Conquest by 125 the Truth Closing (the Kindness Speech) 137 ANNEX 1 - The Dhammapada 140 ANNEX 2 - The Great Establishing of 194 Mindfulness Discourse BIBLIOGRAPHY 216 to 227 3 I present this book, which is the result of notes and university papers written at various times and in various situations, which I have kept as something that could one day be organized in an expository way. The text was composed at the request of my wife, Dedé, who since my adolescence has been paving my Dharma with love, kindness, and gentleness so that the long path would be smoother for my stubborn feet. It is not an academic work, nor a religious text, because I am a rationalist. It is just what I carry with me from many personal pieces of research, analyses, and studies, as an individual object from which I cannot separate myself. I dedicate it to Dede, to all mine, to Prof. Robert Thurman of Columbia University-NY for his teachings, and to all those to whom this text may in some way do good. -

Buddhism and Development: a Background Paper

Religions and Development Research Programme Buddhism and Development: A Background Paper Emma Tomalin Department of Theology and Religious Studies, University of Leeds Research Associate, Religions and Development Research Programme Working Paper 18 - 2007 Religions and Development Research Programme The Religions and Development Research Programme Consortium is an international research partnership that is exploring the relationships between several major world religions, development in low-income countries and poverty reduction. The programme is comprised of a series of comparative research projects that are addressing the following questions: z How do religious values and beliefs drive the actions and interactions of individuals and faith-based organisations? z How do religious values and beliefs and religious organisations influence the relationships between states and societies? z In what ways do faith communities interact with development actors and what are the outcomes with respect to the achievement of development goals? The research aims to provide knowledge and tools to enable dialogue between development partners and contribute to the achievement of development goals. We believe that our role as researchers is not to make judgements about the truth or desirability of particular values or beliefs, nor is it to urge a greater or lesser role for religion in achieving development objectives. Instead, our aim is to produce systematic and reliable knowledge and better understanding of the social world. The research focuses on four countries (India, Pakistan, Nigeria and Tanzania), enabling the research team to study most of the major world religions: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism and African traditional belief systems. The research projects will compare two or more of the focus countries, regions within the countries, different religious traditions and selected development activities and policies. -

A Comparative Study of Bhavacakra Painting

Historical Journal Volume: 12 Number: 1 Shrawan, 2077 Deepak Dong Tamang A Comparative Study of Bhavacakra Painting Deepak Dong Tamang Abstract The Bhavacakra is a symbolic representation of Samsara, a powerful mirror for spiritual aspirants and it is often painted to the left of Tibetan monastery doors. Bhavacakra, ‘wheel of life’ consists of two Sanskrit words ‘Bhava’ and ‘Cakra’. The word bhava means birth, origin, existing etc and cakra means wheel, circle, round, etc. There are some textual materials which suggest that the Bhavacakra painting began during the Buddha lifetime. Bhavacakra is very famous for wall and cloth painting. It is believed to represent the knowledge of release from suffering gained by Gautama Buddha in the course of his meditation. This symbolic representation of Bhavacakra serves as a wonderful summary of what Buddhism is, and also reminds that every action has consequences. It can be also understood by the illiterate persons not needing high education and it shows the path of enlightenment out of suffering in samsara. Mahayana Buddhism is very popular in Asian countries like northern Nepal, India, Bhutan, China, Korean, Japan and Mongolia. So in these countries every Mahayana monastery there is wall painting and Thānkā painting of Bhavacakra. But in these countries there are various designs of Bhavacakra due to artist, culture and nation. Key words: Bhavacakra, wheel of life, Mandala, Karma, Samsāra, Sukhāvati bhuvan, Thānkā Introduction In Buddhism, art has been one of the best tools to understand the Buddha teaching. The wheel of life is very famous for walls and cloth painting. This classical image from the Tibetan Buddhist tradition depicts the psychological states, or realm of existence, associated with an unenlightened state. -

Diamond Sutra) 『菩薩於法,應無所住,行於布施

Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas Sponsored By Pure Land Center & Buddhist LiBrary 1120 E. Ogden Avenue, Suite 108 Naperville, IL 60563 http://www.amitabhalibrary.org Tel: (630) 428-9941; Fax: (630) 428-9961 Presenter: Bert T. Tan / Consultant: Venerable Wu Ling Slide 1 Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas q A quick review Ø Topic One : The Basics èBuddhism is an education, not a religion or a philosophy n It teaches us how to recover our wisdom and regain our Buddha nature n It teaches us how to solve our proBlems through wisdom – an art of living èThe Law of Causality governs everything in the universe èAll sentient Beings possess the same Buddha nature n Our Buddha nature is temporarily lost due to delusion n Our lost Buddha nature can be recovered only via cultivation èKarma refers to an action and its retriBution under the Law of Causality n Good and bad karmas do not offset each other – prevailing ones occur first n Karmas, good or Bad, accumulate over time and do not disappear n When many Bad karmic retriButions come together, they form disasters èCultivation means to stop planting Bad seeds and nurturing Bad conditions, and to, instead, plant good seeds and nurture good conditions Last updated Nov. 2016 Presenter: Bert T. Tan / Consultant: Venerable Wu Ling Slide 2 Buddhism 101: Introduction To Buddhism Lecture 9 – Carrying Out the Six Prajna Paramitas q A quick review Ø Topic Two : The Three Refuges and the Four Reliance -

Encountering Nonduality Through Buddhism and Phenomenology

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 2-28-2020 Creating an Ethics of Love: Encountering Nonduality through Buddhism and Phenomenology Dakota Parmley Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Parmley, Dakota, "Creating an Ethics of Love: Encountering Nonduality through Buddhism and Phenomenology" (2020). University Honors Theses. Paper 812. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.831 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. CREATING AN ETHICS OF LOVE: ENCOUNTERING NONDUALITY THROUGH BUDDHISM AND PHENOMENOLOGY by Dakota Parmley An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in University Honors and Philosophy Thesis Advisor Monica Mueller, Ph.D Portland State University 2020 1 Introduction It seems that many people have a hard time not despairing about the direction the world is heading in the current era. All around us, negativity seems to abound and the question of where humanity is heading starts to ring like a bell in the minds of those who question. Certainly, people have valid reasons to despair at the current state of affairs. Climate change is a pressing issue and many people cannot seem to believe that such an issue exists or matters; it seems that divisiveness is increasing; the amount of raw information and data people are inundated with constantly has created an ignorance by which “facts” can no longer be fully discerned. -

Unit 4 Philosophy of Buddhism

Philosophy of Buddhism UNIT 4 PHILOSOPHY OF BUDDHISM Contents 4.0 Objectives 4.1 Introduction 4.2 The Four Noble Truths 4.3 The Eightfold Path in Buddhism 4.4 The Doctrine of Dependent Origination (Pratitya-samutpada) 4.5 The Doctrine of Momentoriness (Kshanika-vada) 4.6 The Doctrine of Karma 4.7 The Doctrine of Non-soul (anatta) 4.8 Philosophical Schools of Buddhism 4.9 Let Us Sum Up 4.10 Key Words 4.11 Further Readings and References 4.0 OBJECTIVES This unit, the philosophy of Buddhism, introduces the main philosophical notions of Buddhism. It gives a brief and comprehensive view about the central teachings of Lord Buddha and the rich philosophical implications applied on it by his followers. This study may help the students to develop a genuine taste for Buddhism and its philosophy, which would enable them to carry out more researches and study on it. Since Buddhist philosophy gives practical suggestions for a virtuous life, this study will help one to improve the quality of his or her life and the attitude towards his or her life. 4.1 INTRODUCTION Buddhist philosophy and doctrines, based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha, give meaningful insights about reality and human existence. Buddha was primarily an ethical teacher rather than a philosopher. His central concern was to show man the way out of suffering and not one of constructing a philosophical theory. Therefore, Buddha’s teaching lays great emphasis on the practical matters of conduct which lead to liberation. For Buddha, the root cause of suffering is ignorance and in order to eliminate suffering we need to know the nature of existence. -

Buddhism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Buddhism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A statue of Gautama Buddha in Bodhgaya, India. Bodhgaya is traditionally considered the place of his awakening[1] Part of a series on Buddhism Outline · Portal History Timeline · Councils Gautama Buddha Disciples Later Buddhists Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Wings to Awakening Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Schools · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Buddhism (Pali/Sanskrit: बौद धमर Buddh Dharma) is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha (Pāli/Sanskrit "the awakened one"). The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[2] He is recognized by adherents as an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth. Two major branches of Buddhism are recognized: Theravada ("The School of the Elders") and Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"). Theravada—the oldest surviving branch—has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and Mahayana is found throughout East Asia and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Tendai and Shinnyo-en. In some classifications Vajrayana, a subcategory of Mahayana, is recognized as a third branch. -

![NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3032/nepal-kabhrepalanchok-operational-presence-map-as-of-14-july-2015-2093032.webp)

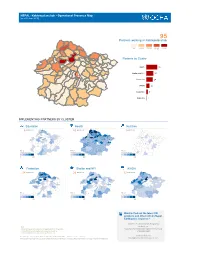

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [as of 14 July 2015] Gairi Bisauna Deupur Baluwa Pati Naldhun Mahadevsthan Mandan Naya Gaun Deupur Chandeni Mandan 86 Jaisithok Mandan Partners working in Kabhrepalanchok Anekot Tukuchanala Devitar Jyamdi Mandan Ugrachandinala Saping Bekhsimle Ghartigaon Hoksebazar Simthali Rabiopi Bhumlutar 1-5 6-10 11-15 16-20 21-35 Nasikasthan Sanga Banepa Municipality Chaubas Panchkhal Dolalghat Ugratara Janagal Dhulikhel Municipality Sathigharbhagawati Sanuwangthali Phalete Mahendrajyoti Bansdol Kabhrenitya Chandeshwari Nangregagarche Baluwadeubhumi Kharelthok Salle Blullu Ryale Bihawar No. of implementing partners by Sharada (Batase) Koshidekha Kolanti Ghusenisiwalaye Majhipheda Panauti Municipality Patlekhet Gotpani cluster Sangkhupatichaur Mathurapati Phulbari Kushadevi Methinkot Chauri Pokhari Birtadeurali Syampati Simalchaur Sarsyunkharka Kapali Bhumaedanda Health 37 Balthali Purana Gaun Pokhari Kattike Deurali Chalalganeshsthan Daraunepokhari Kanpur Kalapani Sarmathali Dapcha Chatraebangha Dapcha Khanalthok Boldephadiche Chyasingkharka Katunjebesi Madankundari Shelter and NFI 23 Dhungkharka Bahrabisae Pokhari Narayansthan Thulo Parsel Bhugdeu Mahankalchaur Khaharepangu Kuruwas Chapakhori Kharpachok Protection 22 Shikhar Ambote Sisakhani Chyamrangbesi Mahadevtar Sipali Chilaune Mangaltar Mechchhe WASH 13 Phalametar Walting Saldhara Bhimkhori Education Milche Dandagaun 7 Phoksingtar Budhakhani Early Recovery 1 Salme Taldhunga Gokule Ghartichhap Wanakhu IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS BY CLUSTER Early Recovery -

Npl Eq Operational Presence K

NEPAL: Kabhrepalanchok - Operational Presence Map [as of 30 June 2015] 95 Partners working in Kabrepalanchok 1-5 6-10 11-15 16-20 21-40 Partners by Cluster Health 40 Shelter and NFI 26 Protection 24 WASH 12 Education 6 Nutrition 1 IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS BY CLUSTER Education Health Nutrition 6 partners 40 partners 1 partners Nb of Nb of Nb of organisations organisations organisations 1 20 1 40 1 20 Protection Shelter and NFI WASH 24 partners 26 partners 12 partners Nb of Nb of Nb of organisations organisations organisations 1 30 1 30 1 20 Want to find out the latest 3W products and other info on Nepal Earthquake response? visit the Humanitarian Response Note: website at Implementing partner represent the organization on the ground, http:www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/op in the affected area doing the operational work, such as erations/nepal distributing food, tents, doing water purification, etc. send feedback to Creation date: 10 July 2015 Glide number: EQ-2015-000048-NPL Sources: Cluster reporting [email protected] The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Kabrepalanchok District Include all activity types in this report? TRUE Showing organizations for all activity types Education Health Nutrition Protection Shelter and NFI WASH VDC Name MSI,UNICEF,WHO AWN,UNWomen,SC N-Npl SC,WA Anekot Balthali UNICEF,WHO MC UNICEF,CN,MC Walting UNICEF,WHO CECI SC,UNICEF TdH AmeriCares,ESAR,UNICEF,UN AAN,UNFPA,KIRDA PI,TdH TdH,UNICEF,WA Baluwa Pati Naldhun FPA,WHO RC Wanakhu UNICEF AWN CECI,GM SC,UNICEF ADRA,TdH Royal Melbourne CIVCT G-GIZ,GM,HDRVG SC,UNICEF Banepa Municipality Hospital,UNICEF,WHO Nepal,CWISH,KN,S OS Nepal Bekhsimle Ghartigaon MSI,UNICEF,WHO N-Npl UNICEF Bhimkhori SC UNICEF,WHO SC,WeWorld SC,UNICEF ADRA MSI,UNICEF,WHO YWN MSI,Sarbabijaya ADRA UNICEF,WA Bhumlutar Pra.bi. -

8 from Geographical Periphery to Conceptual Centre: the Travels of Ngagchang Shakya Zangpo and the Discovery of Hyolmo Identity

Davide Torri 8 From Geographical Periphery to Conceptual Centre: The Travels of Ngagchang Shakya Zangpo and the Discovery of Hyolmo Identity This chapter will explore and analyze dynamics of cultural production in a particular context, the Helambu valley (Nepal). The valley is home to the Hyolmo, a Nepalese minority of Tibetan origin, whose culture seems to have been shaped by the particular agency, within a sacred geography (Yolmo Gangra), of a specific class of cultural agents, namely the so-called reincarnated lamas and treasure discoverers. One of them, in particular, could be considered the cultural hero par excellence of the Hyolmo due to his role in establishing and maintaining long lasting relationships between distant power places, and to his spiritual charisma. His legacy still lives on among the people of Helambu, and his person is still revered as the great master who opened the outer, inner, and secret doors of the Yolmo Gangra. The role of treasure discov- erers – or tertön (gter ston)1 – in the spread of Buddhism across the Himalayas is related to particular conceptions regarding the landscape and especially to the key-theme of the “hidden lands” or beyul (sbas yul). But the bonds linking a community to its territory are not simply an historical by-product. As in the case of the Hyolmo, the relationship between people, landscape, and memory is one of the main features of the identity-construction processes that constitute one of the most relevant elements of contemporary Nepalese politics. 1 Tibetan names and expressions are given in phonetic transcription, with a transliteration ac- cording to the Wylie system added in brackets after their first occurrence (or after a slash when entirely inside brackets).