Unit 4 Philosophy of Buddhism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thinking in Buddhism: Nagarjuna's Middle

Thinking in Buddhism: Nagarjuna’s Middle Way 1994 Jonah Winters About this Book Any research into a school of thought whose texts are in a foreign language encounters certain difficulties in deciding which words to translate and which ones to leave in the original. It is all the more of an issue when the texts in question are from a language ancient and quite unlike our own. Most of the texts on which this thesis are based were written in two languages: the earliest texts of Buddhism were written in a simplified form of Sanskrit called Pali, and most Indian texts of Madhyamika were written in either classical or “hybrid” Sanskrit. Terms in these two languages are often different but recognizable, e.g. “dhamma” in Pali and “dharma” in Sanskrit. For the sake of coherency, all such terms are given in their Sanskrit form, even when that may entail changing a term when presenting a quote from Pali. Since this thesis is not intended to be a specialized research document for a select audience, terms have been translated whenever possible,even when the subtletiesof the Sanskrit term are lost in translation.In a research paper as limited as this, those subtleties are often almost irrelevant.For example, it is sufficient to translate “dharma” as either “Law” or “elements” without delving into its multiplicity of meanings in Sanskrit. Only four terms have been left consistently untranslated. “Karma” and “nirvana” are now to be found in any English dictionary, and so their translation or italicization is unnecessary. Similarly, “Buddha,” while literally a Sanskrit term meaning “awakened,” is left untranslated and unitalicized due to its titular nature and its familiarity. -

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

Self and Non-Self in Early Buddhism (Joaquin Pérez-Remón)

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A.K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS L.M.Joshi Ernst Steinkellner Punjabi University University of Vienna PatiaUi, India Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universitede Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo,Japan Hardwell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northjield, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Roger Jackson University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA Volume 8 1985 Number I CONTENTS I. ARTICLES J. Nagarjuna's Arguments Against Motion, by Kamaleswar Bhattacharya 7 2. Dharani and Pratibhdna: Memory and Eloquence of the Bodhisattvas, by J ens Braarvig 17 3. The Concept of a "Creator God" in Tantric Buddhism, by Eva K. Dargyay 31 4. Direct Perception (Pratyakja) in dGe-iugs-pa Interpre tations of Sautrantika,^/lnw^C. Klein 49 5. A Text-Historical Note on Hevajratantra II: v: 1-2, by lj>onard W.J. van der Kuijp 83 6. Simultaneous Relation (Sahabhu-hetu): A Study in Bud dhist Theory of Causation, by Kenneth K. Tanaka 91 II. BOOK REVIEWS AND NOTICES Reviews: 1. The Books o/Kiu- Te or the Tibetan Buddhist Tantras: A Pre liminary Analysis, by David Reigle Dzog Chen and Zen, by Namkhai Norbu (Roger Jackson) 113 2. Nagarjuniana. Studies in the Writings and Philosophy of Ndgdrjuna, by Chr. Lindtner (Fernando Tola and Carmen Dragonetti) 115 3. Selfless Persons: Imagery and Thought in Theravada Bud dhism, by Steven Collins (Vijitha Rajapakse) 117 4. Self and Non-Self in Early Buddhism, by Joaquin Perez- Remon (VijithaRajapkse) 122 5. -

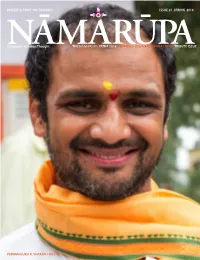

Issue 21 Spring 2016 Digital & Print-On-Demand

DIGITAL & PRINT-ON-DEMAND ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 NĀMARŪPACategories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE PARAMAGURU R. SHARATH JOIS NĀMARŪPA ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 Categories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE Publishers & Founding Editors Robert Moses & Eddie Stern NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 4 THE POSTER & ROUTE MAP Advisors Dr. Robert E. Svoboda GROUP PHOTOGRAPH 6 NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 Meenakshi Moses PALLAVI SHARMA DUFFY 8 WELCOME SPEECH Jocelyne Stern During the Folk Festival at Editors Vishnudevananda Tapovan Kuti Eddie Stern & Meenakshi Moses Design & Production Robert Moses PARAMAGURU 10 CONFERENCES AT TAPOVAN KUTI Proofreading & Transcription R. SHARATH JOIS Transcriptions of talks after class Meenakshi Moses Melanie Parker ROBERT MOSES 28 PHOTO ESSAY Megan Weaver Ashtanga Yoga Sadhana Retreat October 2015 Meneka Siddhu Seetharaman Website www.namarupa.org by BRAHMA VIDYA PEETH Roberto Maiocchi & Robert Moses ACHARYAS 48 TALKS ON INDIAN CULTURE All photographs in Issue 21 SWAMI SHARVANANDA Robert Moses except where noted. SWAMI HARIBRAMENDRANANDA Cover: R. Sharath Jois at Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi, Himalayas. SWAMI MITRANANDA 58 NAVARATRI Back cover: Welcome sign at Kashi Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi. SUAN LIN 62 FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHS October 13, 2015. Analog photography during Yatra 2015 SATYA MOSES DAŚĀVATĀRA ILLUSTRATIONS NĀMARŪPA Categories of Indian Thought, established in 2003, honors the many systems of knowledge, prac- tical and theoretical, that have origi- nated in India. Passed down through अ आ इ ई उ ऊ the ages, these systems have left tracks, a ā i ī u ū paths already traveled that can guide ए ऐ ओ औ us back to the Self—the source of all e ai o au names NĀMA and forms RŪPA. -

Thought and Practice in Mahayana Buddhism in India (1St Century B.C. to 6Th Century A.D.)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences. ISSN 2250-3226 Volume 7, Number 2 (2017), pp. 149-152 © Research India Publications http://www.ripublication.com Thought and Practice in Mahayana Buddhism in India (1st Century B.C. to 6th Century A.D.) Vaishali Bhagwatkar Barkatullah Vishwavidyalaya, Bhopal (M.P.) India Abstract Buddhism is a world religion, which arose in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha (now in Bihar, India), and is based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama who was deemed a "Buddha" ("Awakened One"). Buddhism spread outside of Magadha starting in the Buddha's lifetime. With the reign of the Buddhist Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, the Buddhist community split into two branches: the Mahasaṃghika and the Sthaviravada, each of which spread throughout India and split into numerous sub-sects. In modern times, two major branches of Buddhism exist: the Theravada in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and the Mahayana throughout the Himalayas and East Asia. INTRODUCTION Buddhism remains the primary or a major religion in the Himalayan areas such as Sikkim, Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, the Darjeeling hills in West Bengal, and the Lahaul and Spiti areas of upper Himachal Pradesh. Remains have also been found in Andhra Pradesh, the origin of Mahayana Buddhism. Buddhism has been reemerging in India since the past century, due to its adoption by many Indian intellectuals, the migration of Buddhist Tibetan exiles, and the mass conversion of hundreds of thousands of Hindu Dalits. According to the 2001 census, Buddhists make up 0.8% of India's population, or 7.95 million individuals. Buddha was born in Lumbini, in Nepal, to a Kapilvastu King of the Shakya Kingdom named Suddhodana. -

1 Syllabus for Higher Diploma Course In

Syllabus for Higher Diploma Course in Buddhist Studies (A course applicable to students of the University Department) From the Academic Year 2020–2021 Approved by the Ad-hoc Board of Studies in Pali Literature and Culture Savitribai Phule Pune University 1 Savitribai Phule Pune University Higher Diploma Course in Buddhist Studies General Instructions about the Course, the Pattern of Examination and the Syllabus I. General Instructions I.1 General Structure: Higher Diploma Course in Buddhist Studies is a three-year course of semester pattern. It consists of six semesters and sixteen papers of 50 marks each. I.2 Eligibility: • Passed Advanced Certificate Course in Buddhist Studies • Passed H.S.C. or any other equivalent examination with Sanskrit / Pali / Chinese / Tibetan as one subject. I.3 Duration: Three academic years I.4 Fees: The Admission fee, the Tuition Fee, Examination Fee, Record Fee, Statement of Marks for each year of the three-year Higher Diploma course will be as per the rules of the Savitribai Phule Pune University. I.5 Teaching: • Medium of instruction - English or Marathi • Lectures: Semesters I and II - Four lectures per week for fifteen weeks each Semesters III to VI – Six lectures per week for fifteen weeks each II Pattern of Examination II.1 Assessment and Evaluation: • Higher Diploma Course examination will be held once at the end of each semester of the academic year. • The examination for the Higher Diploma Course will consist of an external examination carrying 40 marks of two hours duration and an internal examination of 10 marks for all the sixteen papers. -

Buddhist Doctrines (Source: Phillip Novak

Buddhist Doctrines (source: Phillip Novak. The World’s Wisdom. Edison, NJ: Castle Books. 1994:65-83.) a. The Three Jewels (The Buddha “the Awakened One,” Dharma (Sanskrit)/Dhamma (Pali) – the way of truth he taught, and the Sangha – the community of those who live by that teaching, are called the Three Jewels because of their purity and inestimable value. They are held as essential by all schools of Buddhism. The triple recitation of the following formula is a basic Buddhist act of piety.) I go for refuge to the Buddha. I go for refuge to the Dharma. I go for refuge to the Sangha. b. The Four Noble Truths (from the Buddha’s first sermon, “Setting Rolling the Wheel of Truth.”) Suffering (Dukkha), as a noble truth, is this: Birth is suffering, ageing is suffering, sickness is suffering, death is suffering, sorrow and pain . and despair are suffering, association with the loathed is suffering, dissociation from the loved is suffering, not to get what one wants is suffering – in short suffering is the five (groups) of clinging’s objects (the five skandhas/skandas or “groupings of existence,” that make up a human individual). Thus the origin of suffering, as a noble truth, is this: It is the craving that produces renewal of being, accompanied by enjoyment and lust – in other words, craving for sensual desires, craving for being, craving for non-being (Tanha). Cessation of suffering, as a noble truth, is this: It is remainderless fading and ceasing, . letting go and rejecting, of that same craving (Nirvana/Sunyata). The way leading to the cessation of suffering, as a noble truth is this: It is simply the eightfold path of (Prajna) right view and right intention, (Sila) right speech, right action and right livelihood, and (Dhyana) right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration. -

Com 23 Draft B

Community Issue 23 - Page 1 Autumn 2005 / 2548 The Upāsaka & Upāsikā Newsletter Issue No. 23 Dagoba at Mahintale Dagoba InIn thisthis issue.......issue....... InIn peoplepeople wewe trusttrust ?? TheThe Temple at Kosgoda The wisdom of the heartheart SicknessSickness——A Teacher AssistedAssisted DyingDying MakingMaking connectionsconnections beyond words BluebellBluebell WalkWalk Community Community Issue 23 - Page 2 In people we trust? Multiculturalism and community relations have been This is a thoroughly uncomfortable position to be in, as much in the news over recent months. The tragedy of anyone who has suffered from arbitrary discrimination can the London bombings and the spotlight this has attest. There is a feeling of helplessness that whatever one thrown on to what is called ‘the Moslem community’ says or does will be misinterpreted. There is a resentment has led me to reflect upon our own Buddhist that one is being treated unfairly. Actions that would pre- ‘community’. Interestingly, the name of this newslet- viously have been taken at face value are now suspected of ter is ‘Community’, and this was chosen in discussion having a hidden agenda in support of one’s group. In this between a number of us, because it reflected our wish situation, rumour and gossip tend to flourish, and attempts to create a supportive and inclusive network of Forest to adopt a more inclusive position may be regarded with Sangha Buddhist practitioners. suspicion, or misinterpreted to fit the stereotype. The AUA is predominantly supported by western Once a community has polarised, it can take a great deal converts to Buddhism. Some of those who frequent of work to re-establish trust. -

A Comparative Study of Bhavacakra Painting

Historical Journal Volume: 12 Number: 1 Shrawan, 2077 Deepak Dong Tamang A Comparative Study of Bhavacakra Painting Deepak Dong Tamang Abstract The Bhavacakra is a symbolic representation of Samsara, a powerful mirror for spiritual aspirants and it is often painted to the left of Tibetan monastery doors. Bhavacakra, ‘wheel of life’ consists of two Sanskrit words ‘Bhava’ and ‘Cakra’. The word bhava means birth, origin, existing etc and cakra means wheel, circle, round, etc. There are some textual materials which suggest that the Bhavacakra painting began during the Buddha lifetime. Bhavacakra is very famous for wall and cloth painting. It is believed to represent the knowledge of release from suffering gained by Gautama Buddha in the course of his meditation. This symbolic representation of Bhavacakra serves as a wonderful summary of what Buddhism is, and also reminds that every action has consequences. It can be also understood by the illiterate persons not needing high education and it shows the path of enlightenment out of suffering in samsara. Mahayana Buddhism is very popular in Asian countries like northern Nepal, India, Bhutan, China, Korean, Japan and Mongolia. So in these countries every Mahayana monastery there is wall painting and Thānkā painting of Bhavacakra. But in these countries there are various designs of Bhavacakra due to artist, culture and nation. Key words: Bhavacakra, wheel of life, Mandala, Karma, Samsāra, Sukhāvati bhuvan, Thānkā Introduction In Buddhism, art has been one of the best tools to understand the Buddha teaching. The wheel of life is very famous for walls and cloth painting. This classical image from the Tibetan Buddhist tradition depicts the psychological states, or realm of existence, associated with an unenlightened state. -

Relevance of Pali Tipinika Literature to Modern World

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) Vol. 1, Issue 2, July 2013, 83-92 © Impact Journals RELEVANCE OF PALI TIPINIKA LITERATURE TO MODERN WORLD GYANADITYA SHAKYA Assistant Professor, School of Buddhist Studies & Civilization, Gautam Buddha University, Greater Noida, Gautam Buddha Nagar, Uttar Pradesh, India ABSTRACT Shakyamuni Gautam Buddha taught His Teachings as Dhamma & Vinaya. In his first sermon Dhammacakkapavattana-Sutta, after His enlightenment, He explained the middle path, which is the way to get peace, happiness, joy, wisdom, and salvation. The Buddha taught The Eightfold Path as a way to Nibbana (salvation). The Eightfold Path can be divided into morality, mental discipline, and wisdom. The collection of His Teachings is known as Pali Tipinika Literature, which is compiled into Pali (Magadha) language. It taught us how to be a nice and civilized human being. By practicing Sala (Morality), Samadhi (Mental Discipline), and Panna (Wisdom ), person can eradicate his all mental defilements. The whole theme of Tipinika explains how to be happy, and free from sufferings, and how to get Nibbana. The Pali Tipinika Literature tried to establish freedom, equality, and fraternity in this world. It shows the way of freedom of thinking. The most basic human rights are the right to life, freedom of worship, freedom of speech, freedom of thought and the right to be treated equally before the law. It suggests us not to follow anyone blindly. The Buddha opposed harmful and dangerous customs, so that this society would be full of happiness, and peace. It gives us same opportunity by providing human rights. -

Buddhist Ethical Education.Pdf

BUDDHIST ETHICAL EDUCATION ADVISORY BOARD His Holiness Thich Tri Quang Deputy Sangharaja of Vietnam Most Ven. Dr. Thich Thien Nhon President of National Vietnam Buddhist Sangha Most Ven.Prof. Brahmapundit President of International Council for Day of Vesak CONFERENCE COMMITTEE Prof. Dr. Le Manh That, Vietnam Most Ven. Dr. Dharmaratana, France Most Ven. Prof. Dr. Phra Rajapariyatkavi, Thailand Bhante. Chao Chu, U.S.A. Prof. Dr. Amajiva Lochan, India Most Ven. Dr. Thich Nhat Tu (Conference Coordinator), Vietnam EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Do Kim Them, Germany Dr. Tran Tien Khanh, USA Nguyen Manh Dat, U.S.A. Bruce Robert Newton, Australia Dr. Le Thanh Binh, Vietnam Giac Thanh Ha, Vietnam Nguyen Thi Linh Da, Vietnam Giac Hai Hanh, Australia Tan Bao Ngoc, Vietnam VIETNAM BUDDHIST UNIVERITY SERIES BUDDHIST ETHICAL EDUCATION Editor Most Ven. Thich Nhat Tu, D.Phil., HONG DUC PUBLISHING HOUSE CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................vii Preface ......................................................................................................ix Editor’s Foreword .................................................................................xiii 1. ‘Nalanda Culture’ as an Archetypal of Global Education in Ethics: An Approach Anand Singh ...............................................................................................1 2. Buddhist Education: Path Leading to the Awakening Hira Paul Gangnegi .................................................................................15 -

Explanation 1 Vinnana and Namarupa-PATICCA SAMUPPADA.Pdf

PATICCASAMUPPADA Part - II The Law of Dependent Origination Consciousness ARISES Mind and Matter 1. Avijja - ignorance or delusion 2. Sankhara - kamma-formations 3. Vinnana - consciousness 4. Nama-rupa - mind and matter 5. Salayatana - six sense bases 6. Phassa - contact or impression 7. Vedana - Feeling 8. Tanha - craving 9. Upadana - clinging 10. Bhava - becoming 11. Jati - rebirth 12. Jara-marana - old age and death Introduction – PA-TIC-CA-SA-MUP-PA-DA – the law of Dependent Origination – is very tedious to study and so is to get a clear understanding of one’s interaction of kamma’s action in the frame work of the present, past and future existence. Lesson No. 1 – Kamma Action Kamma action depends on one’s intention. An individual is not responsible for any kamma action, if he or she has committed a deed without volitional intention. The Arahant Thera CAKKHUPALA THERA was stamping on insects and many were killed, because he was blind. He has no volitional intent to kill the insects; and hence, Buddha said, he is free and not responsible for this action and therefore no kamma is generated against him. “Buddha, the Lord said that since the thera had no intention to kill the insects, he was free from any moral responsibility for their destruction. So we should note that causing death with out cetana or volition is not a kammic act. Some Buddhists have doubt about their moral purity when they cook vegetables or drink water that harbor microbes.” Page 1 of 7 Dhamma Dana Maung Paw, California Buddha said - "Cetana (volitional act) is that which I call kamma." Lesson No.