The Indigenous Peoples and Small

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Report on Gantong/Brooke's Point

1 “THE Mt. GANTONG/BROOKE’S POINT 2010 GEO-TAGGED REPORT” MINING THREATHS TO WATERSHEDS, CORE ZONES AND TO THE ANCESTRAL DOMAIN OF ISOLATED INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES, PALAWAN ISLAND (THE PHILIPPINES) A joint field assessment of ALDAW (Ancestral Land/Domain Watch) and The Centre for Biocultural Diversity (CBCD) of the University of Kent (UK) Between the 12th and 19th of July 2009, a joined ALDAW/CBCD Mission1 traveled to Brooke’s Point Municipality (Palawan) to carry out field reconnaissance and audio-visual documentation of the mountainous areas laying on the eastern side of the Gantong range, where the source of the Linau river (property of barangay Ipilan) is found. The province of Palawan is part of the “Man and Biosphere Reserve” program of UNESCO and hosts 49 animals and 56 botanical species found in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The Gantong range is endowed with the same richness of biological diversity and endemism found in the recently proclaimed Mt. Mantalingahan Protected Area, the best recognized biodiversity hot spot in southern Palawan. A study commissioned by Conservation International-Philippines reveals that several endangered species listed by IUCN (The World Conservation Union) are found around the Mantalingahan Range. 1 The mission was composed by Dr. Dario Novellino PhD. (Anthropologist of the CBCD) and Visiting Research Associate of the Institute of Philippine Culture (IPC) of the Ateneo de Manila University, Mr. Julio Cusurichi Palacios (an indigenous advocate from Peru, and winner of the 2007 Goldman Prize), Mr. Artiso Mandawa (member of the National Anti-Poverty Commission and national campaign coordinator of ALDAW), Mr. -

1.1 Brief History of the Municipality Bataraza Is Named After a Locally

Municipal Comprehensive Land Use Plan, 2009 – 2018 Municipality of Bataraza, Palawan I. GENERAL INFORMATION 1.1 Brief History of the Municipality Bataraza is named after a locally influential Muslim Chieftain, Datu Bataraza Narrazid who was the father of the town's first mayor, Datu Sapiodin Narrazid. Datu Sapiodin Narrazid was a former mayor of the municipality of Brooke’s Point, the mother municipality of Bataraza. The municipality of Bataraza was created on June 18, 1961 by virtue of Republic Act 3425. However, it officially functioned as an independent municipality on January 1, 1964 and established its seat of municipal government in barangay Tarusan by virtue of a municipal resolution with concurrence from the provincial board. During the term of Mayor Hadjes P. Asgali in 1971, the seat of municipal government was transferred to barangay Marangas which was the official municipal site as stipulated in RA 3425. During that period, big haciendas started various agricultural activities and brought in farm laborers recruited from other parts of the country. Modern agricultural technologies were introduced and the government provided irrigation and post harvest facilities. This increased rice production areas and yield of the municipality which eventually make Bataraza as one of the rice granaries of Southern Palawan. Likewise, the municipality is endowed with large mineral deposits. Rio Tuba Nickel Mining Corporation (RTNMC) is one of the pioneer mining companies that explore and utilize the mineral deposits of the municipality. 1.2 Human Resource 1.2.1 Population Distibution From 2000 to 2007 the population of Bataraza rose from 41,230 to 53,430, indicating a growth rate of 3.69 percent. -

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE in the PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-Largest Archipelago in the World Comprising 7,641 Islands

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE IN THE PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-largest archipelago in the world comprising 7,641 islands Current population is 100 million, but projected to reach 125 million by 2030; most people, particularly the poor, depend on biodiversity 114 species of amphibians 240 Protected Areas 228 Key Biodiversity Areas 342 species of reptiles, 68% are endemic One of only 17 mega-diverse countries for harboring wildlife species found 4th most important nowhere else in the world country in bird endemism with 695 species More than 52,177 (195 endemic and described species, half 126 restricted range) of which are endemic 5th in the world in terms of total plant species, half of which are endemic Home to 5 of 7 known marine turtle species in the world green, hawksbill, olive ridley, loggerhead, and leatherback turtles ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE The value of Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) is estimated at $10 billion–$23 billion per year, making wildlife crime the fourth most lucrative illegal business after narcotics, human trafficking, and arms. The Philippines is a consumer, source, and transit point for IWT, threatening endemic species populations, economic development, and biodiversity. The country has been a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity since 1992. The value of IWT in the Philippines is estimated at ₱50 billion a year (roughly equivalent to $1billion), which includes the market value of wildlife and its resources, their ecological role and value, damage to habitats incurred during poaching, and loss in potential -

PDRCP Technical Progress Report June 2017 to May 2018 Katala Foundation Inc

Palawan Deer Research and Conservation Program Technical Progress Report June 2017 to May 2018 Peter Widmann, Joshuael Nuñez, Rene Antonio and Indira D. L. Widmann Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines, June 2018 PDRCP Technical Progress Report June 2017 to May 2018 Katala Foundation Inc. TECHNICAL PROGRESS REPORT PROJECT TITLE: Palawan Deer Research and Conservation Program REPORTING PERIOD: June 2017 to May 2018 PROJECT SITES: Palawan, Philippines PROJECT COOPERATORS: Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff (PCSDS) Concerned agencies and authorities BY: KATALA FOUNDATION, INC. PETER WIDMANN, Program Director INDIRA DAYANG LACERNA-WIDMANN, Program Co-Director ADDRESS: Katala Foundation, Inc. Purok El Rancho, Sta. Monica or P.O. Box 390 Puerto Princesa City 5300 Palawan, Philippines Tel/Fax: +63-48-434-7693 WEBSITE: www.philippinecockatoo.org EMAIL: [email protected] or [email protected] 2 Katala Foundation Inc. Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines PDRCP Technical Progress Report June 2017 to May 2018 Katala Foundation Inc. Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 4 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................ 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ -

Some Data on the Distribution, Conservation Status and Protection of Freshwater Turtles in the Palawan Island Group, Philippines

SOME DATA ON THE DISTRIBUTION, CONSERVATION STATUS AND PROTECTION OF FRESHWATER TURTLES IN THE PALAWAN ISLAND GROUP, PHILIPPINES Pierre Fidenci1 and Reymar Castillo2 1Endangered Species International, 79 Brady Street, San Francisco, CA 94108, USA 2Research Coordinator, Biodiversity Center for Research and Conservation, Palawan State University, Puerto Princesa City, Philippines 5300; Project Manager, Philippine Forest Turtle Project, Endangered Species International – Palawan State University Introduction The Palawan Island Group is located between Mindoro Island and North Borneo, approximately 600km south-west of Manila, Philippines. Islands included in this group are Palawan (the largest island), Busuanga, Culion, Lampacan, Cuyo, Dumaran, Cagayancillo (also called Cagayanes) and Balabac. Palawan is the fifth largest island in the Philippine archipelago with an area of more than 11,000 square km. The biological importance of Palawan is widely recognized both nationally and internationally. It has even been designated as a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO since 1990. The region includes several existing Proclaimed Conservation Areas such as Coron Islands (7,580 hectares), El Nido Marine Reserve (89,140 hectares), Malampaya Sound (90,000 hectares) and Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park. Palawan has also been declared a mangrove reserve. Palawan has about 422 terrestrial and known marine vertebrate species. This number accounts for about 39% of all the vertebrate species found in the Philippines. Many of the species are endemic to Palawan and have restricted ranges confined to a small area (PCSDS, 2005). The Philippine forest turtle (Siebenrockiella (= Panayenemys) leytensis) (Fig. 1) is one of the most endangered turtle species in the world and the most endangered turtle of the Philippines (Conservation International, 2003; IUCN, 2009). -

Palawan Liner Shipping Developmentak Routes Report

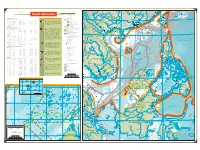

LINER SHIPPING ROUTE STUDY FINAL REPORT VOLUME IX PALAWAN LINER SHIPPING DEVELOPMENTAK ROUTES REPORT November 1994 Submitted to United States Agency for International Development Manila, Philippines Support for Development Program 11: Philippine Sea Transport Consultancy Project No. 492-0450 Prepared by Nathan Associates Inc. under Contract No. 492-0450-C-00-2157-00 The Liner Shipping Route Stutly (LSRS) and the MARINA and SHIPPERCON STUDY (MARSH Study) were conducted, during 1993-1994, under the Philippine Sea Transport Consultancy (PSTC). The Final Report of the LSRS comprises 14 volumes and the Final Report of the MARSH Study comprises 5 volumes. This technical assistance was made possible through the support provided by the Office of Program Economics, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mission in the Philippines. The views, expressions and opinions contained in this and other volumes of the LSRS Final :Report are those of the authors and of Nathan Associates, and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID. 1. INTRODVCTION 1 Development Route Reports Palawan Island & Ports PALSDERR Developmental Route Proposals Organization of PALSDERR- 2. PALAUAN INTERISLAND SHIPPING EiERVICES & PORT TRAFFIC 9 3. CARGO SERVICE STANDARDS 21 Fishery Products Livestock 4. PASSENGER SERVICE STANDARDS 25 5. PUERTO PRINCESA-CEBU LINER SH1:PPING DEVELOPHENTAL ROUTE Liner Service Options Market Analysis PALSDERR Procedure 30 Puerto Princesa 1991-1993 Cargo Flows 32 Trade with Cebu Trade with Manila Puerto Princesa-Cebu-Air Passenger Traffic 35 Economic Analysis 37 6. PALAWAN-ZAHBOANGA LINER SHIPPING DEVELOPHENTAL ROUTE Liner Service Options Market Analysis Sulu Sea Service Option 40 Cagayan de Tawi Tawi Opt ion 4 1 Eccirlomic Analysis 42 7. -

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

Spratly Islands

R i 120 110 u T4-Y5 o Ganzhou Fuqing n h Chenzhou g Haitan S T2- J o Dao Daojiang g T3 S i a n Putian a i a n X g i Chi-lung- Chuxiong g n J 21 T6 D Kunming a i Xingyi Chang’an o Licheng Xiuyu Sha Lung shih O J a T n Guilin T O N pa Longyan T7 Keelung n Qinglanshan H Na N Lecheng T8 T1 - S A an A p Quanzhou 22 T'ao-yüan Taipei M an T22 I L Ji S H Zhongshu a * h South China Sea ng Hechi Lo-tung Yonaguni- I MIYAKO-RETTO S K Hsin-chu- m c Yuxi Shaoguan i jima S A T21 a I n shih Suao l ) Zhangzhou Xiamen c e T20 n r g e Liuzhou Babu s a n U T Taichung e a Quemoy p i Meizhou n i Y o J YAEYAMA-RETTO a h J t n J i Taiwan C L Yingcheng K China a a Sui'an ( o i 23 n g u H U h g n g Fuxing T'ai- a s e i n Strait Claimed Straight Baselines Kaiyuan H ia Hua-lien Y - Claims in the Paracel and Spratly Islands Bose J Mai-Liao chung-shih i Q J R i Maritime Lines u i g T9 Y h e n e o s ia o Dongshan CHINA u g B D s Tropic of Cancer J Hon n Qingyuan Tropic of Cancer Established maritime boundary ian J Chaozhou Makung n Declaration of the People’s Republic of China on the Baseline of the Territorial Sea, May 15, 1996 g i Pingnan Heyuan PESCADORES Taiwan a Xicheng an Wuzhou 21 25° 25.8' 00" N 119° 56.3' 00" E 31 21° 27.7' 00" N 112° 21.5' 00" E 41 18° 14.6' 00" N 109° 07.6' 00" E While Bandar Seri Begawan has not articulated claims to reefs in the South g Jieyang Chaozhou 24 T19 N BRUNEI Claim line Kaihua T10- Hsi-yü-p’ing Chia-i 22 24° 58.6' 00" N 119° 28.7' 00" E 32 19° 58.5' 00" N 111° 16.4' 00" E 42 18° 19.3' 00" N 108° 57.1' 00" E China Sea (SCS), since 1985 the Sultanate has claimed a continental shelf Xinjing Guiping Xu Shantou T11 Yü Luxu n Jiang T12 23 24° 09.7' 00" N 118° 14.2' 00" E 33 19° 53.0' 00" N 111° 12.8' 00" E 43 18° 30.2' 00" N 108° 41.3' 00" E X Puning T13 that extends beyond these features to a hypothetical median with Vietnam. -

PCCP Technical Progress Report September-December 2013 Katala Foundation Inc

In-Situ Conservation Project Technical Progress Report September - December 2013 Peter Widmann and Indira D. L. Widmann Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines August 2014 PCCP Technical Progress Report September-December 2013 Katala Foundation Inc. TECHNICAL PROGRESS REPORT COUNTRY: PHILIPPINES PROJECT TITLE: PHILIPPINE COCKATOO CONSERVATION PROGRAMME In-situ Conservation Project PROJECT DURATION: September - December 2013 PROJECT SITE: Palawan, Philippines PROJECT COOPERATORS: Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Municipal Government of Narra, Palawan, Philippines Municipal Government of Dumaran, Palawan, Philippines Municipal Government of Rizal, Palawan, Philippines Municipal Government of Balabac, Philippines Municipal Government of Patnanungan, Quezon, Philippines Municipal Government of Polillo, Quezon, Philippines Bgy. Culasian Government, Rizal, Palawan, Philippines Bgy. Burdeos Government, Polillo, Quezon, Philippines Bgy. Pandanan Government, Balabac, Palawan, Philippines Local Protected Area Management Committees (LPAMC) Sagip Katala Movement-Narra Chapter, Inc. (SKM-NC, Inc) Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff (PCSDS) Jewelmer Corporation Inc. Polillo Islands Biodiversity Conservation Foundation, Inc. Concerned agencies and authorities BY: KATALA FOUNDATION, INC. INDIRA DAYANG LACERNA-WIDMANN, Program Manager PETER WIDMANN, Program Co-Manager/Scientific Director ADDRESS: Katala Foundation, Inc. 2nd Flr., JMV Bldg., National Highway, Sta. Monica or P.O. Box 390 Puerto Princesa City 5300 Palawan, -

The World Bank for OFFICIAL USE ONLY

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 363 17-PH PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF JAPANESE YEN 11.710 MILLION (USSl 00 MILLIONEQUIVALENT) TO THE LAND BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES WITH THE GUMTEEOF THE REPtlBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Public Disclosure Authorized FOR A SUPPORT FOR STRATEGIC LOCAL DEVELOPMENT AND INVESTMENT PROJECT May 3 1,2006 Urban Development Sector Unit East Asia and Pacific Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective May 1,2006) Currency Unit = Philippine Pesos (PhP) PhP51.5 = US$1 PhP 1.00 = US$0.019 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 3 1 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asia Development Bank BAC Bids and Awards Committee BSP Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas CAS Country Assistance Strategy CDS City Development Strategy CIDA Canada International Development Agency COA Commission on Audit DBP Development Bank of the Philippines DENR Department of Environment and Natural Resources EA Environment Assessment ECC Environmental Compliance Certificate EIS Environment Impact Study EMP EnvironmentalManagement Plan FM Financial Management FS Feasibility Study FSL Fixed Spread Loan GFI Government Financial Institution GOP Government of the Philippines GPPB Government Procurement Policy Board HBD Harmonized -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population

2010 Census of Population and Housing Marinduque Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population MARINDUQUE 227,828 BOAC (Capital) 52,892 Agot 502 Agumaymayan 525 Amoingon 1,346 Apitong 405 Balagasan 801 Balaring 501 Balimbing 1,489 Balogo 1,397 Bangbangalon 1,157 Bamban 443 Bantad 1,405 Bantay 1,389 Bayuti 220 Binunga 691 Boi 609 Boton 279 Buliasnin 1,281 Bunganay 1,811 Maligaya 707 Caganhao 978 Canat 621 Catubugan 649 Cawit 2,298 Daig 520 Daypay 329 Duyay 1,595 Ihatub 1,102 Isok II Pob. (Kalamias) 677 Hinapulan 672 Laylay 2,467 Lupac 1,608 Mahinhin 560 Mainit 854 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Marinduque Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Malbog 479 Malusak (Pob.) 297 Mansiwat 390 Mataas Na Bayan (Pob.) 564 Maybo 961 Mercado (Pob.) 1,454 Murallon (Pob.) 488 Ogbac 433 Pawa 732 Pili 419 Poctoy 324 Poras 1,079 Puting Buhangin 477 Puyog 876 Sabong 176 San Miguel (Pob.) 217 Santol 1,580 Sawi 1,023 Tabi 1,388 Tabigue 895 Tagwak 361 Tambunan 577 Tampus (Pob.) 1,145 Tanza 1,521 Tugos 1,413 Tumagabok 370 Tumapon 129 Isok I (Pob.) 1,236 BUENAVISTA 23,111 Bagacay 1,150 Bagtingon 1,576 Bicas-bicas 759 Caigangan 2,341 Daykitin 2,770 Libas 2,148 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Marinduque Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City,