Detailed Species Accounts from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRUSTVETASSISTSSURVIVAL of WORLD'srarestparrot New Clues to Echo Parakeet Problem Bypallia Harris

News about parrot conservation, aviculture and welfare from qg&%rld q&rrot~t TRUSTVETASSISTSSURVIVAL OF WORLD'SRARESTPARROT New clues to Echo Parakeet problem ByPallIa Harris When the World Parrot Trust was The World Parrot Trust has project, contributing funds and of the World Parrot Trust and a launched in 1989, our first consistently provided funding for parrot expertise to both the member of the International Zoo priority was to help the world's the Echo Parakeet and maintained captive breeding programme and Veterinary Group. When the rarest parrot, the Echo Parakeet, close relations with the project's wild population management captive population of parrots which still numbers less than 20 director, Carl Jones, and the efforts. This new opportunity became ill this spring, Andrew birds in the wild. With your Jersey Wildlife Preservation provides the World Parrot Trust advised project staff in Mauritius generous donations, the Trust Trust, which finances and with one of the greatest by telephone and by fax. was proud to present the Echo manages the project with the co- challenges in parrot conservation Subsequently, at the request of Parakeet project with a badly operation of the Mauritius today. the Jersey Wildlife Preservation needed four wheel drive vehicle government's Conservation Unit. The followingstory is drawn, Trust, the World Parrot Trust sent to enable field researchers to Recently, the World Parrot Trust in part, from a veterinary report Andrew to Mauritius to reach the remote forest in which was invited to become a major by Andrew Greenwood,MAVetMB investigate tragic mortalities the parrot struggles to survive. partner in the Echo Parakeet MIBiolMRCVS,a founder Trustee among the Echo Parakeets. -

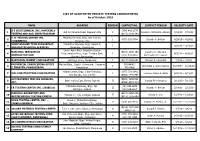

III III III III LIST of ACCREDITED PRIVATE TESTING LABORATORIES As of October 2019

LIST OF ACCREDITED PRIVATE TESTING LABORATORIES As of October 2019 NAME ADDRESS REGION CONTACT NO. CONTACT PERSON VALIDITY DATE A’S GEOTECHNICAL INC. MATERIALS (074) 442-2775 1 Old De Venecia Road, Dagupan City I Dioscoro Richard B. Alviedo 7/16/19 – 7/15/21 TESTING AND SOIL INVESTIGATION (0917) 1141-343 E. B. TESTING CENTER INC. McArthur Hi-way, Brgy. San Vicente, 2 I (075) 632-7364 Elnardo P. Bolivar 4/29/19 – 4/28/21 (URDANETA) Urdaneta City JORIZ GROUND TECH SUBSURFACE MacArthur Highway, Brgy. Surabnit, 3 I 3/20/18 – 3/19/20 AND GEOTECHNICAL SERVICES Binalonan, Pangasinan Lower Agno River Irrigation System NATIONAL IRRIGATION (0918) 8885-152 Ceferino C. Sta. Ana 4 Improvement Proj., Brgy. Tomana East, I 4/30/19 – 4/29/21 ADMINISTRATION (075) 633-3887 Rommeljon M. Leonen Rosales, Pangasinan 5 NORTHERN CEMENT CORPORATION Labayug, Sison, Pangasinan I (0917) 5764-091 Vincent F. Cabanilla 7/3/19 – 7/2/21 PROVINCIAL ENGINEERING OFFICE Malong Bldg., Capitol Compound, Lingayen, 542-6406 / 6 I Antonieta C. Delos Santos 11/23/17 – 11/22/19 (LINGAYEN, PANGASINAN) Pangasinan 542-6468 Valdez Center, Brgy. 1 San Francisco, (077) 781-2942 7 VVH CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION I Francisco Wayne B. Butay 6/20/19 – 6/19/21 San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte (0966) 544-8491 ACCURATEMIX TESTING SERVICES, (0906) 4859-531 8 Brgy. Muñoz East, Roxas, Isabela II Juanita Pine-Ordanez 3/11/19 – 3/10/21 INC. (0956) 4078-310 Maharlika Highway, Brgy. Ipil, (02) 633-6098 9 EB TESTING CENTER INC. (ISABELA) II Elnardo P. Bolivar 2/14/18 – 2/13/20 Echague, Isabela (02) 636-8827 MASUDA LABORATORY AND (0917) 8250-896 10 Marana 1st, City of Ilagan, Isabela II Randy S. -

The Philippines Hotspot

Ecosystem Profile THE PHILIPPINES HOTSPOT final version December 11, 2001 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 The Ecosystem Profile 3 The Corridor Approach to Conservation 3 BACKGROUND 4 BIOLOGICAL IMPORTANCE OF THE PHILIPPINES HOTSPOT 5 Prioritization of Corridors Within the Hotspot 6 SYNOPSIS OF THREATS 11 Extractive Industries 11 Increased Population Density and Urban Sprawl 11 Conflicting Policies 12 Threats in Sierra Madre Corridor 12 Threats in Palawan Corridor 15 Threats in Eastern Mindanao Corridor 16 SYNOPSIS OF CURRENT INVESTMENTS 18 Multilateral Donors 18 Bilateral Donors 21 Major Nongovernmental Organizations 24 Government and Other Local Research Institutions 26 CEPF NICHE FOR INVESTMENT IN THE REGION 27 CEPF INVESTMENT STRATEGY AND PROGRAM FOCUS 28 Improve linkage between conservation investments to multiply and scale up benefits on a corridor scale in Sierra Madre, Eastern Mindanao and Palawan 29 Build civil society’s awareness of the myriad benefits of conserving corridors of biodiversity 30 Build capacity of civil society to advocate for better corridor and protected area management and against development harmful to conservation 30 Establish an emergency response mechanism to help save Critically Endangered species 31 SUSTAINABILITY 31 CONCLUSION 31 LIST OF ACRONYMS 32 2 INTRODUCTION The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is designed to better safeguard the world's threatened biodiversity hotspots in developing countries. It is a joint initiative of Conservation International (CI), the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. CEPF provides financing to projects in biodiversity hotspots, areas with more than 60 percent of the Earth’s terrestrial species diversity in just 1.4 percent of its land surface. -

Bridges Across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia

Bridges across Oceans Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia April 2010 0 2010 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. Published 2010. Printed in the Philippines ISBN 978-971-561-896-0 Publication Stock No. RPT101731 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Bridges across Oceans: Initial Impact Assessment of the Philippines Nautical Highway System and Lessons for Southeast Asia. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2010. 1. Transport Infrastructure. 2. Southeast Asia. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ADB encourages printing or copying information exclusively for personal and noncommercial use with proper acknowledgment of ADB. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works for commercial purposes without the express, written consent of ADB. Note: In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 -

Assessment of Impediments to Urban-Rural Connectivity in Cdi Cities

ASSESSMENT OF IMPEDIMENTS TO URBAN-RURAL CONNECTIVITY IN CDI CITIES Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 JANUARY 27, 2017 This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) and do not necessarily reflect the view of USAID or the United States Agency for International Development USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page i Pre-Feasibility Study for the Upgrading of the Tagbilaran City Slaughterhouse ASSESSMENT OF IMPEDIMENTS TO URBAN-RURAL CONNECTIVITY IN CDI CITIES Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 Program Title: USAID/SURGE Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Philippines Contract Number: AID-492-H-15-00001 Contractor: International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Date of Publication: January 27, 2017 USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page ii Assessment of Impediments to Urban-Rural Connectivity in CDI Cities Contents I. Executive Summary 1 II. Introduction 7 II. Methodology 9 A. Research Methods 9 B. Diagnostic Tool to Assess Urban-Rural Connectivity 9 III. City Assessments and Recommendations 14 A. Batangas City 14 B. Puerto Princesa City 26 C. Iloilo City 40 D. Tagbilaran City 50 E. Cagayan de Oro City 66 F. Zamboanga City 79 Tables Table 1. Schedule of Assessments Conducted in CDI Cities 9 Table 2. Cargo Throughput at the Batangas Seaport, in metric tons (2015 data) 15 Table 3. -

Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences

/ JOURNAL OF THE WASHINGTON ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Vol. 11 Deckmber 19, 1921 No. 21 ZOOLOGY.—A key to the Philippine operculate Imid mollusks of the genus Ceratopoma.i Paul Bartsch, United States National Museum. In 1918 we published in this Journal^ a Classification of the Philip- pine operculate land shells of the family Helicinidae, with a synopsis of the species and sub-species of the genus Geophorus. In that paper we gave keys to the subgenera and species of the largest genus, namely, Geophorus, of the subfamily Helicinidae. Since then enough ma- terial has come to hand to enable us to similarly treat another genus, namely, that of Ceratopoma, a key to the species of which is herewith furnished (see page 502). Ceratopoma has the operculum less specialized than any other Philippine Helicinid. It consists of a simple, horny shell without calcareous deposit. The type of the genus is Helicina caroli Kobelt. The animal, like Geophorus, is usually a ground dweller and may be found among dead leaves as well as in crevices of rocks. At the present time the genus is known from Luzon, Leyte, Siargao and northeastern Mindanao, and it is quite possible that careful collect- ing in the islands between the two extremes will reveal additional species. Ceratopoma caroli Kobelt comes from the island of Siargao. It is a large species, with the parietal callus chestnut brown. In fact, it is the only Ceratopoma so far known with a brown callus. Ceratopoma henningiana Mollendorff was described from Pena Blanca, Luzon, and differs from all the other Ceratopomas in having a broad brown basal band near the periphery. -

Ecology and Behaviour of Tarsius Syrichta in the Wild

O',F Tarsius syrichta ECOLOGY AND BEHAVIOUR - IN BOHOL, PHILIPPINES: IMPLICATIONS FOR CONSERVATION By Irene Neri-Arboleda D.V.M. A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Applied Science Department of Applied and Molecular Ecology University of Adelaide, South Australia 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS DAge Title Page I Table of Contents............ 2 List of Tables..... 6 List of Figures.... 8 Acknowledgements... 10 Dedication 11 I)eclaration............ t2 Abstract.. 13 Chapter I GENERAL INTRODUCTION... l5 1.1 Philippine Biodiversity ........... t6 1.2 Thesis Format.... l9 1.3 Project Aims....... 20 Chapter 2 REVIEIV OF TARSIER BIOLOGY...... 2t 2.1 History and Distribution..... 22 2.t.1 History of Discovery... .. 22 2.1.2 Distribution...... 24 2.1.3 Subspecies of T. syrichta...... 24 2.2 Behaviour and Ecology.......... 27 2.2.1 Home Ranges. 27 2.2.2 Social Structure... 30 2.2.3 Reproductive Behaviour... 3l 2.2.4 Diet and Feeding Behaviour 32 2.2.5 Locomotion and Activity Patterns. 34 2.2.6 Population Density. 36 2.2.7 Habitat Preferences... ... 37 2.3 Summary of Review. 40 Chapter 3 FßLD SITE AI\D GEIYERAL METHODS.-..-....... 42 3.1 Field Site........ 43 3. 1.1 Geological History of the Philippines 43 3.1.2 Research Area: Corella, Bohol. 44 3.1.3 Physical Setting. 47 3.t.4 Climate. 47 3.1.5 Flora.. 50 3.1.6 Fauna. 53 3.1.7 Human Population 54 t page 3.1.8 Tourism 55 3.2 Methods.. 55 3.2.1 Mapping. -

Directory of Participants 11Th CBMS National Conference

Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Academe Dr. Tereso Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI Dr. Marideth Bravo De La Salle University-AKI Associate Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 Ms. Nelca Leila Villarin E-Mail: [email protected] Social Action Minister for Adult Formation and Advocacy De La Salle Zobel School Mr. Gladstone Cuarteros Tel No: (02) 771-3579 LJPC National Coordinator E-Mail: [email protected] De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 7212000 local 608 Fax: 7248411 E-Mail: [email protected] Batangas Ms. Reanrose Dragon Mr. Warren Joseph Dollente CIO National Programs Coordinator De La Salle- Lipa De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 756-5555 loc 317 Fax: 757-3083 Tel No: 7212000 loc. 611 Fax: 7260946 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Camarines Sur Brother Jose Mari Jimenez President and Sector Leader Mr. Albino Morino De La Salle Philippines DEPED DISTRICT SUPERVISOR DEPED-Caramoan, Camarines Sur E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Dina Magnaye Assistant Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Cavite Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 E-Mail: [email protected] Page 1 of 78 Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ms. Rosario Pareja Mr. Edward Balinario Faculty De La Salle University-Dasmarinas Tel No: 046-481-1900 Fax: 046-481-1939 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE in the PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-Largest Archipelago in the World Comprising 7,641 Islands

ADDRESSING ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE IN THE PHILIPPINES PHILIPPINES Second-largest archipelago in the world comprising 7,641 islands Current population is 100 million, but projected to reach 125 million by 2030; most people, particularly the poor, depend on biodiversity 114 species of amphibians 240 Protected Areas 228 Key Biodiversity Areas 342 species of reptiles, 68% are endemic One of only 17 mega-diverse countries for harboring wildlife species found 4th most important nowhere else in the world country in bird endemism with 695 species More than 52,177 (195 endemic and described species, half 126 restricted range) of which are endemic 5th in the world in terms of total plant species, half of which are endemic Home to 5 of 7 known marine turtle species in the world green, hawksbill, olive ridley, loggerhead, and leatherback turtles ILLEGAL WILDLIFE TRADE The value of Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) is estimated at $10 billion–$23 billion per year, making wildlife crime the fourth most lucrative illegal business after narcotics, human trafficking, and arms. The Philippines is a consumer, source, and transit point for IWT, threatening endemic species populations, economic development, and biodiversity. The country has been a party to the Convention on Biological Diversity since 1992. The value of IWT in the Philippines is estimated at ₱50 billion a year (roughly equivalent to $1billion), which includes the market value of wildlife and its resources, their ecological role and value, damage to habitats incurred during poaching, and loss in potential -

Analyses of Proposals to Amend

CoP17 Prop. 10 Transfer of Philippine Pangolin Manis culionensis from Appendix II to Appendix I Proponents: Philippines and United States of America Summary: The Philippine Pangolin Manis culionensis is endemic to six islands in the Philippines: mainland Palawan and the much smaller adjacent islands of Coron, Culion, Balabac, Busuanga and Dumaran Island. It has also been introduced to Apulit Island adjacent to Palawan. Pangolin populations in the Philippines were previously considered part of the Sunda Pangolin Manis javanica, but were split from it in 2005. The species occurs in lowland primary and secondary forests, grasslands/secondary growth mosaics, mixed mosaics of agricultural lands and scrubland adjacent to secondary forests. It is solitary and typically gives birth annually to one young after a gestation period of approximately six months1. It is thought that breeding occurs in August and September. Generation time is taken as seven years. There is a lack of population data, mainly because the species is elusive, solitary and nocturnal. In 2004 it was described by local people as fairly common, though subject to moderately heavy hunting pressure2. There are relatively recent (2012) estimates of densities of 0.05 individuals per km2 in primary forest and 0.01 per km2 in mixed forest/brush land3. Higher estimates made in 2014 of 2.5 adult pangolins per km2 on Palawan and Dumaran Island are considered unreliable4. The species is thought still to be considerably more abundant in northern and central Palawan than in the south; it is reportedly abundant on Dumaran Island (435km2). Local hunters on Palawan report that populations are declining as a result of hunting. -

Zamboanga Peninsula Regional Development

Contents List of Tables ix List of Figures xv List of Acronyms Used xix Message of the Secretary of Socioeconomic Planning xxv Message of the Regional Development Council IX xxvi Chairperson for the period 2016-2019 Message of the Regional Development Council IX xxvii Chairperson Preface message of the National Economic and xxviii Development Authority IX Regional Director Politico-Administrative Map of Zamboanga Peninsula xxix Part I: Introduction Chapter 1: The Long View 3 Chapter 2: Global and Regional Trends and Prospects 7 Chapter 3: Overlay of Economic Growth, Demographic Trends, 11 and Physical Characteristics Chapter 4: The Zamboanga Peninsula Development Framework 27 Part II: Enhancing the Social Fabric (“Malasakit”) Chapter 5: Ensuring People-Centered, Clean and Efficient 41 Governance Chapter 6: Pursuing Swift and Fair Administration of Justice 55 Chapter 7: Promoting Philippine Culture and Values 67 Part III: Inequality-Reducing Transformation (“Pagbabago”) Chapter 8: Expanding Economic Opportunities in Agriculture, 81 Forestry, and Fisheries Chapter 9: Expanding Economic Opportunities in Industry and 95 Services Through Trabaho at Negosyo Chapter 10: Accelerating Human Capital Development 113 Chapter 11: Reducing Vulnerability of Individuals and Families 129 Chapter 12: Building Safe and Secure Communities 143 Part IV: Increasing Growth Potential (“Patuloy na Pag-unlad”) Chapter 13: Reaching for the Demographic Dividend 153 Part V: Enabling and Supportive Economic Environment Chapter 15: Ensuring Sound Macroeconomic Policy -

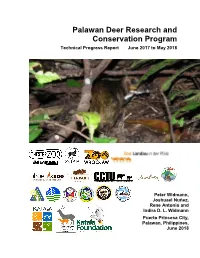

PDRCP Technical Progress Report June 2017 to May 2018 Katala Foundation Inc

Palawan Deer Research and Conservation Program Technical Progress Report June 2017 to May 2018 Peter Widmann, Joshuael Nuñez, Rene Antonio and Indira D. L. Widmann Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines, June 2018 PDRCP Technical Progress Report June 2017 to May 2018 Katala Foundation Inc. TECHNICAL PROGRESS REPORT PROJECT TITLE: Palawan Deer Research and Conservation Program REPORTING PERIOD: June 2017 to May 2018 PROJECT SITES: Palawan, Philippines PROJECT COOPERATORS: Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff (PCSDS) Concerned agencies and authorities BY: KATALA FOUNDATION, INC. PETER WIDMANN, Program Director INDIRA DAYANG LACERNA-WIDMANN, Program Co-Director ADDRESS: Katala Foundation, Inc. Purok El Rancho, Sta. Monica or P.O. Box 390 Puerto Princesa City 5300 Palawan, Philippines Tel/Fax: +63-48-434-7693 WEBSITE: www.philippinecockatoo.org EMAIL: [email protected] or [email protected] 2 Katala Foundation Inc. Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines PDRCP Technical Progress Report June 2017 to May 2018 Katala Foundation Inc. Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 4 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................ 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................