Continuity Or Change in Egyptian Foreign Policy Under Mubarak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Accords Anwar Sadat

WMHSMUN XXXIV After the Accords: Anwar Sadat’s Cabinet Background Guide “Unprecedented committees. Unparalleled debate. Unmatched fun.” Letters From the Directors Dear Delegates, Welcome to WMHSMUN XXXIV! My name is Hank Hermens and I am excited to be the in-room Director for Anwar Sadat’s Cabinet. I’m a junior at the College double majoring in International Relations and History. I have done model UN since my sophomore year of high school, and since then I have become increasingly involved. I compete as part of W&M’s travel team, staff our conferences, and have served as the Director of Media for our college level conference, &MUN. Right now, I’m a member of our Conference Team, planning travel and training delegates. Outside of MUN, I play trumpet in the Wind Ensemble, do research with AidData and for a professor, looking at the influence of Islamic institutions on electoral outcomes in Tunisia. In my admittedly limited free time, I enjoy reading, running, and hanging out with my friends around campus. As members of Anwar Sadat’s cabinet, you’ll have to deal with the fallout of Egypt’s recent peace with Israel, in Egypt, the greater Middle East and North Africa, and the world. You’ll also meet economic challenges, rising national political tensions, and more. Some of the problems you come up against will be easily solved, with only short-term solutions necessary. Others will require complex, long term solutions, or risk the possibility of further crises arising. No matter what, we will favor creative, outside-the-box ideas as well as collaboration and diplomacy. -

Implicación Del Terrorismo En El Conflicto Palestino-Israelí Desde La

Universidad CEU Cardenal Herrera Departamento de Derecho Público IMPLICACIÓN DEL TERRORISMO EN EL CONFLICTO PALESTINO ISRAELÍ DESDE LA ÉPOCA DEL MANDATO BRITÁNICO HASTA LA ACTUALIDAD TESIS DOCTORAL Presentada por: María Carmen Forriol Campos Dirigida por: Susana Sanz Caballero Valencia Año 2016 A mis padres Francisco y Carmen a quienes con este trabajo de investigación sólo puedo agradecer un poco de lo mucho que se preocuparon por nuestra formación 1 AGRADECIMIENTOS Quiero agradecer en primer lugar a la Doctora Susana Sanz Caballero su permanente accesibilidad y disponibilidad para resolver cualquier duda o consulta y porque con sus indicaciones ha hecho posible que se hiciese realidad este trabajo de investigación. También quiero agradecer la accesibilidad y la información facilitada por todas aquellas personas a las que he tenido la oportunidad de entrevistar personal, telefónicamente y en el mismo Israel y a las que hago mención a lo largo de este trabajo. Mi profundo agradecimiento a todas esas amistades que tanto interés han mostrado por este trabajo y que de alguna manera han contribuido a que se haya hecho realidad. Quiero también agradecer el apoyo y afecto de mis hermanos que desde la cercanía han hecho factible el arduo proceso de elaboración de esta Tesis Doctoral. 2 3 INDICE ACRÓNIMOS 8 INTRODUCCIÓN GENERAL 12 1. Formulación de Hipotesis 31 2. Justificación y objetivos de la Tesis 31 3. Estructura 32 4. Metodología de la Investigación 33 5. Fuentes 35 CAPÍTULO I EL CONFLICTO PALESTINO ISRAELÍ DESDE SUS INICIOS HASTA LA PROCLAMACIÓN DE ISRAEL COMO ESTADO INDEPENDIENTE 38 1. Antecedentes históricos y origen del conflicto 41 1.1. -

Mubarak, Hussein Act Together to Find Partners for Talks

.. .... Arab-Israel JERUSALEM POST MARsms N_,gotUiwns: u.s. tic~ wh1> often kill one another." according to the Egyptian view. Mubarak, Hussein Sp~:aking about relations with Israel. Ali said: ·•Bilateral relations ar.: there . All we have to do is to lZive life to the peace treatv. In fact. act together to find lsradis are cwrywhere. ·as tourists, lllurnalists and in the Academic Cultural Centre which has been re newc~ . ·· Ali takes pride in the fact partners for talks that tomorrow he will OJ)<!n the "During his visit in Washington Egyptian fair which will include an ByARIRATH next week. President Mubarak will Israeli pavill ion , just as he opened Jerusalem Post Cort'epondent clarify to President Reagan how one the book fair. including an Israeli CAIRO.- Egyptian Prime Minster can keep up the peace momentum stand. ~e' era I weeks ago~ Kamal Hassan Ali said yesterday following the meeting with Hussein Stressing that one ha-s to build now that new steps are being taken in full and the Hussein-Arafat agree for the future and should not dwell coordination with King Hussein to ment." Ali said. to0 much on the past. Ali neverthe C't resolve the problem of forming a less voices a. number of complaints, ~ Ali hoped that following Mubar- joint Jordanian-Palestinian delega . ak's Washington visit. the U.S. .. which in his view soured relations. 0 tion including moderate Palesti- r:: would again step up its active in "We should not speak about the last nians. volvement in the Middle East for the two-three years. -

NUMBER TEN ARMY and POLITICS in MUBARAK's EGYPT ROBERT B. SATLOFF W THE

POUCY PAPERS • NUMBER TEN ARMY AND POLITICS IN MUBARAK'S EGYPT ROBERT B. SATLOFF w THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EASTPOUCY 50 F STREET, N.W. • SUITE 8800 • WASHINGTON, D.C. 20001 THEAUTHOR Robert B. Satloff is a Fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, specializing in contemporary Arab and Islamic politics. He is the author of Troubles on the East Bank: Challenges to the Domestic Stability of Jordan (Center for Strategic and International Studies with Praeger, 1986) and 'They Cannot Stop Our Tongues:' Islamic Activism in Jordan (Washington Institute Policy Paper Number Five, December 1986). In addition, his articles on various Middle Eastern issues have appeared in such publications as the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, Newsday, Middle Eastern Studies and Middle East Insight. Mr. Satloff is also a member of The Washington Institute's Presidential Study Group on U.S. Policy in the Middle East. A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express his appreciation to all those armed forces officers, government officials, politicians, diplomats, scholars, journalists and private citizens from Egypt, Israel and the United States - too numerous to list - who offered their advice and insights during the preparation of this Policy Paper. In addition, the following people were gracious enough to read earlier drafts of the paper and offer their comments, suggestions and criticisms: William J. Burns; W. Seth Carus; Shai Feldman; Daniel Kurtzer and Ehud Yaari. Moreover, the author is deeply grateful for the good counsel of colleagues at The Washington Institute, as well as the valuable research assistance provided by Douglas Pasternak, Bart Aronson and Barbara Fedderly. -

The Register, 1979-03-16

North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship NCAT Student Newspapers Digital Collections 3-16-1979 The Register, 1979-03-16 North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister Recommended Citation North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University, "The Register, 1979-03-16" (1979). NCAT Student Newspapers. 798. https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister/798 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in NCAT Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TH£4<5 REGISTER " COMPLETE AWARENESS FOR COMPLETE COMMITMENT" VOLUME XIX NUMBER 38 NORTH CAROLINA AGRICULTURAL AND TECHNICAL STATE UNIVERSITY GREENSBORO JMC MARCH 16. 1979 Student Prexy Speaks On HEW 3-Day Tour By Andrew McCorkle "Duplication does not In an office decorated in necessarily mean elimination late 19th century paper work, of programs at Black Richard Gordon, Student schools." Government Association He said that often a president, said candidly, predominantly Black school and a white school in the same geographical location will Cabinet offer the same programs that Approves emphasize different aspects of a subject even though they Proposal may have the same course title. CAIRO, EGYPT (AP) Gordon said he was unable Egyptian Cabinet today to hold a private conference approved the proposed peace with Dr. Mary Berry, HEW's treaty with Israel, and assistant secretary for President Anwar Sadat said education and one of five he hoped the historic pact federal officials who visited PHOTO BY WOOr.v could be signed in Washington A&T last month. -

Nael M. Shama Phd Thesis

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by St Andrews Research Repository THE FOREIGN POLICY OF EGYPT UNDER MUBARAK: THE PRIMACY OF REGIME SECURITY Nael M. Shama A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2008 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/569 This item is protected by original copyright The Foreign Policy of Egypt under Mubarak: The Primacy of Regime Security (A Thesis Submitted for the Award of the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy) Nael M. Shama School of International Relations University of St. Andrews February 2008 1 I, Nael Shama, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 105000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. Date: signature of candidate ……… I was admitted as a research student in September 2003 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2004; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2003 and 2007. date signature of candidate ……… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of …………..in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

La Política Exterior De Uruguay Hacia Los Países Africanos Durante Los Gobiernos

UNIVERSIDAD DE LA REPÚBLICA Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Departamento de Sociología Tesis final para postular al título de Magíster en Estudios Contemporáneos de América Latina. La Política Exterior de Uruguay hacia los países africanos durante los gobiernos del Frente Amplio (2005-2017): ¿construcción de nuevas relaciones Sur-Sur? Autor: Gonzalo Exequiel Castillo Gasco Tutor: Prof. Dr. Lincoln Bizzozero Revelez. Docente grado 5. Titular. Montevideo, Uruguay. 2019. Página de aprobación. Título de la tesis: La Política Exterior de Uruguay hacia los países africanos durante los gobiernos del Frente Amplio (2005-2017): ¿construcción de nuevas relaciones Sur-Sur? Autor: Gonzalo Exequiel Castillo Gasco Tutor: Prof. Dr. Lincoln Bizzozero Revelez. Fecha de defensa: _____________________________ Integrantes del tribunal evaluador: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Calificación: _______ ii Resumen La presente investigación analiza la Política Exterior de Uruguay hacia los países africanos entre 2005 y 2017, durante los gobiernos del Frente Amplio. Busca abordar dos objetivos generales: el primero es comparar la Política Exterior de Uruguay hacia África entre 2005 y 2017 con la Política Exterior de Uruguay hacia los países africanos anterior. El segundo es identificar si la Política Exterior implementada por Uruguay hacia África entre 2005 y 2017 se orientó por los ideales y principios que dan contenido a las relaciones Sur-Sur. Para abordar esos objetivos se realiza una investigación cualitativa de documentación del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y entrevistas semiestructuradas a diplomáticos y tomadores de decisión de dicho Ministerio que estuvieron involucrados de algún modo en los vínculos con África. Se define y distinguen los conceptos de cooperación Sur-Sur y relaciones Sur-Sur, y se identifican sus principios rectores. -

ATION REPORT Olj the CONTRACEPTIVE PREVALENCE STUDIES PROJECT AMY ONG TSUI 1?

EVALt!ATION REPORT OlJ THE CONTRACEPTIVE PREVALENCE STUDIES PROJECT A Report Prepared By: AMY ONG TSUI 1?h.D. JAY H. GGASS~~, Ph.D. JOHN A. ROSS, Ph.D. During The Period: JuLY 19-29, 1983 Supported By The: U. S. AGENCY FOr- IN'rEHNATIOi'U\L DEVELOPHENT (ADSS) AID/DSPE-C-0053 AUTHORIZA':L'ION~ Ltr. AID/DS/POP~ 1/6/84 Assgn. No. 582209 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The evaluation team is grateful for the timely assistance and cooperation extended by Westinghouse Health Systems and the Office of Population at AID towards assembling the information needed to complete this evaluation and for the supporting services of the American Public Health Association in coordinating the evaluation. -i- CONTENTS Page ACKNO~'lLEDGMENTS . • . • . • . • . i AB B REV I AT ION S. .. vii LISTOFTABLES •.•......•...•.•..•...•...•..••••.••.•............• ix I . SUMMARY ...... • ••••• 90 • D •••• " • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 II. EVALUATION METHODOLOGY ......... .. 7 Composition of Team ........... · ... 7 Dates and Places of Evaluation .• . • • 0 • • e • ... 7 Materials Evaluated .. • • • • iii • • 8 Basic Questions ..... .0. ....... • • • • • • • • • • 8 III. EXTERNAL FACTORS. • • • fI · .... 13 country Select ion .. 13 Funding Certainty ...... .. 13 IV. INPUTS ...... • • ., • 0 • • • • • .... 17 Contractor Inputs. 17 AID Inputs 22 V. OUTPUTS .. .' ..... 25 Further Development of Survey Documentation .. 25 Selection of Participating Countries. · .. 26 Subcontractor Selection. 27 Field Opera t ions .............. 29 Monitoring Field Operations .... 29 Data Processing and Analysis. 30 Further Analysi s ........... 0 •• 33 VI. PURPOSE ..•.•••.•••••••••.••• 0 • 0 •••••••••••• 0 ••••• 0 •••••• 35 VII. GOAL OF THE PROJECT .................................... 37 VIII. BENEFICIARIES ..... 39 Data Produced and Available for Family Planning Program Management ..... 39 Use of the Survey Results for Family Planning Program Management . ..... 41 "Further Analyses", A Potential Source of Useful " Re sui t s ........ -

KING HASSAN II: Morocco's Messenger of Peace BY

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks KING HASSAN II: Morocco’s Messenger of Peace BY C2007 Megan Melissa Cross Submitted to the Department of International Studies and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts _________________________ Chair _________________________ Co-Chair _________________________ Committee Member Date Defended: ___________ The Thesis Committee for Megan Melissa Cross certifies That this is the approved version of the following thesis: KING HASSAN II: Morocco’s Messenger of Peace Committee: _________________________ Chair _________________________ Co-Chair _________________________ Committee Member Date approved: ___________ ii ABSTRACT Megan Melissa Cross M.A. Department of International Studies, December 2007 University of Kansas The purpose of this thesis is to examine the roles King Hassan II of Morocco played as a protector of the monarchy, a mediator between Israel and the Arab world and as an advocate for peace in the Arab world. Morocco’s willingness to enter into an alliance with Israel guided the way for a mutually beneficial relationship that was cultivated for decades. King Hassan II was a key player in the development of relations between the Arab states and Israel. His actions illustrate a belief in peace throughout the Arab states and Israel and also improving conditions inside the Moroccan Kingdom. My research examines the motivation behind King Hassan II’s actions, his empathy with the Israeli people, and his dedication to finding peace not only between the Arab states and Israel, but throughout the Arab world. -

Corruption in Egypt…A Dark Cloud That Does Not Vanish" Ibn Khaldoun "Introduction"

Kefaya (enough) to cleanse Egypt! "Judicial and documentary file" "Corruption in Egypt…A dark cloud that does not vanish" Ibn Khaldoun "Introduction" Index Introduction to Hurt Egypt Corruption rules in Egypt " Corruption Government" (Corruptionistan) Egypt is a model example for the corruption phenomenon. First Section: The Political Regime Corruption Second Section: Corruption in Government Sectors: Agriculture – Investment – Banks – Culture- Health- Oil- Public Business Sector- Media. Third Section: The most well known corruption issues and its most well-known figures in Mubarak's Egypt. Fourth Section: Hidden Corruption. Conclusion: enough An outline f the most important elements of the press statement: 1-Seriousness of the issue, and spread of its phenomenon, and accidents. 2-Documentation of corruption crimes in both the present and the future of this nation since Mubarak assumed power in early 1980s. Being so many and hidden make us feel that corruption is bigger than our efforts and understanding during Mubarak's era. 3- Corruption in this report is a comprehensive phenomenon: there are various kinds of corruption; obvious, hidden, political, cultural, economic, social ….it even becomes a social law (status quo). 4- The report confirmed that corruption was the main reason for wasting several opportunities of development in addition to corrupt associations, brain drain, weak construction amid a high rate of only destruction and selling. Five relying on some cases that were settled while others are still pending due to the influence of defendants. Introduction to the Harmed Egyptian Nation! Corruption rules in Egypt "Corruption Government" (Corruptionistan)?! The main problem of corruption is not only related to the successive arrests of its figures who belong to or may be close to the ruling regime, such a series is no longer interesting as it has been repeated several times. -

Military After Egypt's Military Steps Into Politics, Will Politics Step Into the Military?

E-PAPER Policy Brief Egypt 4 – Military After Egypt's military steps into politics, will politics step into the military? ANONYMOUSLY In order to protect the identity of the author, the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung has chosen to publish the paper without naming the author. After Egypt's military steps into politics, will politics step into the military? by Anonymous Contents Preface to the Series 3 An institution under stress from within 4 The revolution catches the generals off-guard 4 Cracks at the top 6 Sisi's purges 8 Sisi unchallenged? 9 Imprint 13 Preface to the Series Policy Brief Egypt Contrary to external appearances and official propaganda, the Egyptian Armed Forces are not a unified and cohesive actor, and Abdelfattah al-Sisi is far from being an undisputed leader. Rather, the military is a collective actor criss-crossed by rival networks which the President manages but does not control. While dramatic internal rifts are unlikely to occur, political challenges – for instance, an even further deterioration of the economy – may well change the calculus of relevant actors. Somewhat paradoxically, the ever-wider remit of military power may well carry the seed for substantial conflicts of interest leading to new coalitions and power equations. External actors should not confuse the current political atrophy with stability: in the medium term, internal competition will grow. If politics is banned and crowded out by military authoritarianism, then political conflict will penetrate into the core of «the military institution» itself. After the uprising against President Hosni Mubarak of January 2011, the Egyptian armed forces emerged as the dominant actor on the political scene. -

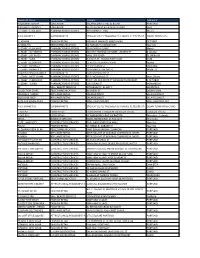

Merchant Name Business Type Address Address 2 NAZEEM

Merchant Name Business Type Address Address 2 NAZEEM BUTCHERY EDUCATION SALAH ELDIN ST AND EL BAZAR PORTSAID BRILLIANCE SCHOOLS EDUCATION KILLO 26 CAIRO ALEX DESERT ROAD GIZA EL EZABY - ELSALAM E PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 516 KORNISH ELNILE Maadi ALFA MARKET 1 SUPERMARKETS ETISALAT CO. EL TAGAMOA EL KHAMES -ELTESEEN ST DOWN TOWN BLD., EL ADHAM FASHION RETAIL MEHWAR MARKAZY ABAZIA MALL OCTOBER ELHANA TEL TELECOMMUNICATION 12 HASSAN EL MAMOUN ST. Nasr city EL EZABY - ELSALAM E PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 516 KORNISH ELNILE Maadi EL EZABY - OCTOBER U PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 283 HAY 7 BEHIND OCTOBER UNIVERCITY 6 October EL EZABY - SKY PLAZA PHARMACY/DRUG STORES MALL SKY PLAZA EL SHEROUK EL EZABY - SUEZ PHARMACY/DRUG STORES ELGALAA ST, ASWAN INSTITUION SUEZ EL EZABY - ELDARAISA PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 11 KILO15 ALEX-MATROUH Agamy EL EZABY- SHOBRA 2 PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 113 SHOUBRA ST. SHOUBRA EL EZABY- ZAMALEK 2 PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 6A ELMALEK ELAFDAL ST. ZAMALEK KHAYRAT ZAMAN MARKET SUPERMARKETS HATEM ROUSHDY ST EL EZABY - MEET GHAM PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 37 ELMOQAWQS ST Meet Ghamr EL EZABY - ELMEHWAR PHARMACY/DRUG STORES PIECE 101,3RD DISTRICT,MEHWAR ELMARKAZY 6 OCTOBER EL EZABY - SUDAN PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 166 SUDAN ST. MOHANDSIN EV SPA / BEAUTY SERVICES 278 HEGAZ ST. EL HAY 7 HELIOPOLIS COLLECTION STARS TELECOMMUNICATION 39 SHERIF ST. DOWNTOWN SAMSUNG ASWAN APPLIANCE RETAIL SALAH ELDIN ST SALAH ELDIN ST GOLD LINE SHOP APPLIANCE RETAIL SALAH ELDIN ST SALAH ELDIN ST ELITE FOR SHOES ASWA FASHION RETAIL MALL ASWAN PLAZA MALL ASWAN PLAZA ALFA MARKET S3 SUPERMARKETS ETISALAT CO. EL TAGAMOA EL KHAMES -ELTESEEN ST- DOWN TOWN-NEW CAIRO ELSHEIBY FOOD RETAIL 124 MASR WEL SUDAN ST.HADDayek El koba Haddayek El koba ELSHEIBY 2 FOOD RETAIL 67 SAKR KORICH BLD.SHERATTON Sheratton - Helipolis SIR KIL BUSINESS SERVICES 328 EL NARGES BLD.