Adventures at the Interplay of Poetry and Computer Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Accessibility in VR with Reused Motion Input

Replay to Play: Creating Accessibility in VR with Reused Motion Input A Technical Report presented to the faculty of the School of Engineering and Applied Science University of Virginia by Cody Robertson May 8, 2020 On my honor as a University student, I have neither given nor received unauthorized aid on this assignment as defined by the Honor Guidelines for Thesis-Related Assignments. Signed: ___________________________________________________ Approved: ______________________________________ Date _______________________ Seongkook Heo, Department of Computer Science Replay to Play: Creating Accessibility in VR with Reused Motion Input Abstract Existing virtual reality (VR) games and applications tend not to factor in accommodations for varied levels of user ability. To enable users to better engage with this technology, a tool was developed to record and replay captured user motion to reduce the strain of complicated gross motor motions to a simple button press. This tool allows VR users with any level of motor impairment to create custom recordings of the motions they need to play VR games that have not designed for such accessibility. Examples of similar projects as well as recommendations for improvements are given to help round out the design space of accessible VR design. Introduction In many instances, high-end in-home virtual reality is synonymous with a head-mounted display (HMD) on the user’s face and motion-tracked controllers, simulating the hand’s ability to grip and hold objects, in a user’s hands. This is the case with all forms of consumer available HMD that is driven by a traditional computer rather than an integrated computer, including the Oculus Rift, Valve Index, HTC Vive, the variously produced Windows Mixed Reality HMDs, and Playstation VR with the Move Controllers. -

Blast Off Broken Sword

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES Broken Sword blast off Revolution’s fight Create a jetpack in for survival Unreal Engine 4 Issue 15 £3 wfmag.cc TEARAWAYS joyful nostalgia and comic adventure in knights and bikes UPGRADE TO LEGENDARY AG273QCX 2560x1440 A Call For Unionisation hat’s the first thing that comes to mind we’re going to get industry-wide change is collectively, when you think of the games industry by working together to make all companies improve. and its working conditions? So what does collective action look like? It’s workers W Is it something that benefits workers, getting together within their companies to figure out or is it something that benefits the companies? what they want their workplace to be like. It’s workers When I first started working in the games industry, AUSTIN within a region deciding what their slice of the games the way I was treated wasn’t often something I thought KELMORE industry should be like. And it’s game workers uniting about. I was making games and living the dream! Austin Kelmore is across the world to push for the games industry to But after twelve years in the industry and a lot of a programmer and become what we know it can be: an industry that horrible experiences, it’s now hard for me to stop the Chair of Game welcomes everyone, treats its workers well, and thinking about our industry’s working conditions. Workers Unite UK, allows us to make the games we all love. That’s what a a branch of the It’s not a surprise anymore when news comes out Independent Workers unionised games industry would look like. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

Bit Y Aparte | N.º 1

SELLO ARSGAMES | Nº 1 | Enero 2014 Revista interdisciplinar de estudios videolúdicos EDITORIAL ARTE En el bit de Bit y aparte Hibridaciones contempo- / pág. 7 ráneas: el nuevo ambiente estético / pág. 8 María Luján Oulton / Eurídice Cabañes Martínez #ÍNDICE COMITÉ CIENTÍFICO ARTE EDUCACIÓN GÉNERO Implicaciones de aprender a God of War: consecuencias de Género y sexualidad más allá FLAVIO ESCRIBANO (España). Doctor por la Universidad Complu- crear videojuegos / pág. 22 la violencia a través de héroe de lo humano / pág. 50 tense de Madrid con la tesis doctoral “El videojuego como he- griego/ pág. 36 rramienta para la pedagogía artística. Innovación y creatividad”. Jacinto Quesnel Alvarez Juan Francisco Belmonte Ávila Begoña Cadiñanos Martínez / GRACIELA ESNAOLA (Argentina). Docente del Programa de Doc- Ruth García Martín torado “Formación del Profesorado en Entornos Virtuales”. Uni- versidad de Valencia. BIT Y APARTE GONZALO FRASCA (Uruguay). Catedrático de Videojuegos de la Facultad de Comunicación y Diseño de la Universidad ORT. Revista interdisciplinar de estudios videolúdicos ÓCAR GARCÍA PANELLA (España). Director del Grado en Vi- deojuegos de ENTIUB, del Máster en Gamificación ENTIUB y del Edita: Asociación ARSGAMES Máster en Gamifiación Online y Transmedia Storytelling de IEBS. Ilustración de la portada: PATRICIA GOUVEIA (Portugal). Profesora en el master de Arte digi- Juan Díaz-Faes GAME STUDIES GAME STUDIES INNOVACIÓN tal en la Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas. Universidade Evolución histórica de los CRPG Aprendizaje en MMOG Videojuegos, machinima y cine Diseño de portada, ilustración y Nova de Lisboa. (Computer Role-Playing Games) / pág. 84 clásico / pág. 94 producción gráfica: / pág. 64 MAR MARCOS MOLANO (España). Profesora Titular en la Facultad de SELLO ARSGAMES Ruth S. -

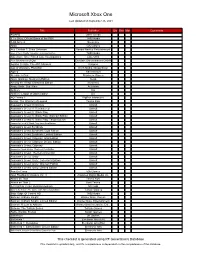

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Programme Edition

JOURNEE 13h00 - 18h00 WEEK END 14h00 - 19h00 JOURJOURJOUR Vendredi 18/12 - 19h00 Samedi 19/12 Dimanche 20/12 Lundi 21/12 Mardi 22/12 ThèmeThèmeThème Science Fiction Zelda & le J-RPG (Jeu de rôle Japonais) ArcadeArcadeArcade Strange Games AnimeAnimeAnime NES / Twin Famicom / MSXMSXMSX The Legend of Zelda Rainbow Islands Teenage Mutant Hero Turtles SC 3000 / Master System Psychic World Streets of Rage Rampage Super Nintendo Syndicate Zelda Link to the Past Turtles in Time + Sailor Moon Megadrive / Mega CD / 32X32X32X Alien Soldier + Robo Aleste Lunar 2 + Soleil Dynamite Headdy EarthWorm Jim + Rocket Knight Adventures Dragon Ball Z + Quackshot Nintendo 64 Star Wars Shadows of the Empire Furai no Shiren 2 Ridge Racer 64 Buck Bumble SaturnSaturnSaturn Deep Fear Shining Force III scénario 2 Sky Target Parodius Deluxe Pack + Virtual Hydlide Magic Knight Rayearth + DBZ Shinbutouden Playstation Final Fantasy VIII + Saga Frontier 2 Elemental Gearbolt + Gun Blade Arts Tobal n°1 Dreamcast Ghost Blade Spawn Twinkle Star Sprites Alice's Mom Rescue Gamecube F Zero GX Zelda Four Swords 4 joueurs Bleach Playstation 2 Earth Defense Force Code Age Commanders / Stella Deus Puyo Pop Fever Earth Defense Force Cowboy Bebop + Berserk XboxXboxXbox Panzer Dragoon Orta Out Run 2 Dead or Alive Xtreme Beach Volleyball Wii / Wii UWii U / Wii JPWii JP Fragile Dreams Xenoblade Chronicles X Devils Third Samba De Amigo Tatsunoko vs Capcom + The Skycrawlers Playstation 3 Guilty Gear Xrd Demon's Souls J Stars Victory versus + Catherine Kingdom Hearts 2.5 Xbox 360 / XBOX -

Gaming Systems and Features of Discovery Centre Station 1

Gaming systems and features of Discovery Centre Station 1: XBox 1 with Remote The Book of Unwritten Tales 2 Wii U and Wii U Remote Braid Playstation 4 with Remote The Bridge Gaming PC with Gaming keyboard and The Cat and the Coup mouse Cave Story+ Downloaded games in station 1 include: Closure 7 Grand Steps, Step 1: What Ancients Begat Cogs 140 Coil AaAaAA!! – A Reckless Disregard for Colosse Gravity Colour Bind ABE VR Crawl Achron Cube & Star: An Arbitrary Love AltscpaceVR Dayz Amnesia: The Dark Descent Deep Under the Sky Analogue: A Hate Story Desktop Dungeons A Story About My Uncle Destinations B.U.T.T.O.N. Dinner Date Bad Hotel Dream Banished The Dream Machine Bastion The Dream Machine: Chapter 3 The Beginner’s Guide The Dream Machine: Chapter 4 Besiege The Dream Machine: Chapter 5 Between IGF Demo Dungeon of the Endless Bientôt l’été Dust: An Elysian Tail Bigscreen Beta Elegy for a Dead World BioShock Infinite Endless Legend The Binding of Isaac: Rebirth Ephemerid: A Musical Adventure BIT.TRIP RUNNER Estranged: Act 1 BlazeRush Carleton University Library and the Discovery Centre September 2019 Euro Truck Simulator 2 Interstellar Marines Evoland Intrusion 2 Evoland 2 Invisible, Inc. Fallout Jamestown Fallout 2 Joe Danger Fallout Tactics Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes Farming Simulator 17 Kentucky Route Zero Flotilla LA Cops FLY’N Legend of Dungeon The FOO show Life is Strange The Forest LIMBO Fotonica Lisa Frozen Synapse Little Inferno FTL: Faster than -

“Lessons Learned, from Games Preserved”

“Lessons Learned, from Games Preserved” James “Ender” Brown Former Project Lead – http://www.scummvm.org/ [email protected] WhoWho AmAm II ● Grew up gaming and learning to code with the BBC Micro/Archimedes, Commodore 16(!) and Amiga – learnt Unix & VMS by doing naughty things to the Tassie VAX cluster (any locals remember davros and typhoon? :) ● Retro-Gaming Enthusiast by night, Systems Admin for a Perth-based Data Centre and Hosting Company by day ● Became Project Lead of ScummVM in Feb 2002, retiring as co-lead (from a team of 3) in Dec 2008 ● 10th linux.conf.au, first talk submission :) WhatWhat isis ScummVM?ScummVM? ● ScummVM is a collection of interpreter implementations for classic adventure games ● Founded by Ludwig ‘ludde’ Strivegus (uTorrent, OpenTTD, now at Spotify) in 2001, along with Vincent ‘yaz0r’ Hamm (now at Oculus), with the goal of building an interpreter for SCUMM-based games by LucasArts/LucasFilm games. ● Designed to be highly portable ● … evolved to become something much much more PortabilityPortability ● ScummVM architecture evolved early on to maximise portability by abstracting backend and common functions (‘Osystem’), with each port supplying a Osystem backend class (with platform specific overrides and subclassing where necessary) Osystem Backend Osystem Common Engine (Platform Specific) ● Carefully developed coding standards to encompass ‘lowest-common- denominator’ C++ implementations. No STL, Exceptions, etc http://wiki.scummvm.org/index.php/Coding_Conventions ● Ssennaidne ● Endianness ● Segment size limits on various platforms ReimplementingReimplementing EnginesEngines ● Most game studios developed their own engines, often used across a family of games. Examples: SCUMM (LucasArts), AGI/SCI (Sierra), Virtual Theatre (Revolution), AGOS (Adventure Soft) ● Reverse engineer: – Container files – Graphics formats (background, actors, sprites) – Audio formats (voice, sfx, music) – Scripting engine (where scripted.. -

FCJ-170 Challenging Hate Speech with Facebook Flarf: the Role of User Practices in Regulating Hate Speech on Facebook

The Fibreculture Journal issn: 1449-1443 DIGITAL MEDIA + NETWORKS + TRANSDISCIPLINARY CRITIQUE issue 23: General Issue 2014 FCJ-170 Challenging Hate Speech With Facebook Flarf: The Role of User Practices in Regulating Hate Speech on Facebook. Benjamin Abraham University of Western Sydney Abstract: This article makes a case study of ‘flarfing’ (a creative Facebook user practice with roots in found-text poetry) in order to contribute to an understanding of the potentials and limitations facing users of online social networking sites who wish to address the issue of online hate speech. The practice of ‘flarfing’ involves users posting ‘blue text’ hyperlinked Facebook page names into status updates and comment threads. Facebook flarf sends a visible, though often non-literal, message to offenders and onlookers about what kinds of speech the responding activist(s) find (un)acceptable in online discussion, belonging to a category of agonistic online activism that repurposes the tools of internet trolling for activist ends. I argue this practice represents users attempting to ‘take responsibility’ for the culture of online spaces they inhabit, promoting intolerance to hate speech online. Careful consideration of the limits of flarf’s efficacy within Facebook’s specific regulatory environment shows the extent to which this practice and similar responses to online hate speech are constrained by the platforms on which they exist. 47 FCJ-170 fibreculturejournal.org FCJ-170 Challenging Hate Speech With Facebook Flarf Introduction A recent spate of high profile cases of online abuse has raised awareness of the amount, volume and regularity of abuse and hate speech that women and minorities routinely attract online. -

Bass-Alt3-Manual

CONTENTS CHAIRMANS FORWARD ....................... 2 REICH S. COMMANDER .... .. ... 3 BRIEFING NOTES ..... .. 4 OBSERVATION LIST . ... 6 t(; Mtiftwe,lft; fo«!" !.o«!"S' ~o I t'udilf a;laee, eaffe;/ tk (/a,o. /~e, t'u-ea' wt't/. a;e,aeefaf tl'-ile, of !f/lllraM fol" aS' folfj aS' I ea,, !'-l}!lre,11rlU<. Tori~ aS' ll«!" SUSPECTS tl'-ila.flearft!'- /NMiete.rl, S'Um'tf fo!'-eM f!'-llllr r;flfiolf (}!-c, CQ/lre to !JIU" LAMB. GILBERT ............................ .. .. 7 foea.tilll(. Tk? We!'-e Ill(~ i!fterMtedi!f fr",ir/t'trj /life 11ralf, 11re. U/!.? / rlolf C EINBECK. ANITA ............ 8 COLSTON , VIC .......................................... 9 tl(IJ«I, HOBBINS, HOWARD ... ........ 10 BONNEVIALLE , VINCENT ..... .. .. .... ............... 11 lffte!'- lu'trj foNed at falf ;01",it 1",ito tk klet!'-alfJ'/lll"t, llrJP ;e,aeefafu-iff~ BURKE , SURGEON . ................. 12 GODDARD, KIT .................... ...................... 13 waS' rlut,.o,rted. It waS' tklf t!.at I u-owea'!'-Wt,lfjt.. I 11raJ't{t',irl w!.o waS' GILLATI, JEROME ..... .... ............... 14 l"M/'lll(S'1ble fol' lN'trji'trj 11re k!'-e alfrl !.alfl'trj S'll 11ra'W' 1',il(oeelft/'e°/'fe i;fferl. PIERMONT, DANIELLE ............................. .... 1 S ERHARD, BEVERLEY .. .. .... .. 16 LIFELY, PAMELA ...... ..................................... 17 WARD, HUTCH ............................... ........... 18 RATGIRL ..................................................... 19 8efo!'-e /flea' tk t!'-alfJ'/lll"t, / waS' a.lie to !'-Ulllfe!'- t/.e e!.a!'-aete!'- loa!'-rlf!'-011r DODDS, DINGO ........................................ 20 KEARNS, KIPPER ..................... ................... 21 ilrj' l'-lllotie eollr/'alfilll(, Joe?· / waS' af.s.o a.lie to /Nl(J t!.ue S'U«!"1'tf 11ral(aafs. WHIM, DOUGLAS ................ .. ..... 22 alfrl frlu a.loat t!.t:r e1-C, a!frlitJ' !'-Mldel(t.i'. -

GAMING GLOBAL a Report for British Council Nick Webber and Paul Long with Assistance from Oliver Williams and Jerome Turner

GAMING GLOBAL A report for British Council Nick Webber and Paul Long with assistance from Oliver Williams and Jerome Turner I Executive Summary The Gaming Global report explores the games environment in: five EU countries, • Finland • France • Germany • Poland • UK three non-EU countries, • Brazil • Russia • Republic of Korea and one non-European region. • East Asia It takes a culturally-focused approach, offers examples of innovative work, and makes the case for British Council’s engagement with the games sector, both as an entertainment and leisure sector, and as a culturally-productive contributor to the arts. What does the international landscape for gaming look like? In economic terms, the international video games market was worth approximately $75.5 billion in 2013, and will grow to almost $103 billion by 2017. In the UK video games are the most valuable purchased entertainment market, outstripping cinema, recorded music and DVDs. UK developers make a significant contribution in many formats and spaces, as do developers across the EU. Beyond the EU, there are established industries in a number of countries (notably Japan, Korea, Australia, New Zealand) who access international markets, with new entrants such as China and Brazil moving in that direction. Video games are almost always categorised as part of the creative economy, situating them within the scope of investment and promotion by a number of governments. Many countries draw on UK models of policy, although different countries take games either more or less seriously in terms of their cultural significance. The games industry tends to receive innovation funding, with money available through focused programmes. -

Full Game Development

CREATIVE AGENCY PRESENTATION FULL GAME DEVELOPMENT June 2021 CREATIVE AGENCY PRESENTATION PROUD TO WORK WITH STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL CREATIVE AGENCY PRESENTATION EXTENSIVE IP EXPERIENCE We carefully study the IP's history and lore and follow every small detail to avoid costly mistakes. We create new content in precisely defined limitations and work closely with IP holders for timely approvals. STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL CREATIVE AGENCY PRESENTATION TECHNOLOGY FOCUS EXPERTISE Our experience with Unity along with certification from Playstation to Xbox, Nintendo and Apple Arcade allow us to provide powerful solutions for our customers. Focus: Mobile & cross-platform development / C# Platforms: Mobile / Switch / Cloud CREATIVE AGENCY PRESENTATION CREATIVE APPROACH CORNERSTONES Game Design Expertise Align creative vision with your business goals with thought-through game design, game economy design, and level design for optimal pacing and enjoyment. And we have experts in all three areas. GAME IDEA & UNIQUE MECHANICS SEARCHING Producer's Vision During the vision formation & pre-production phase we test We strive to deliver an exceptional gaming experience: our game’s market fit to avoid mistakes during development, producer keeps a hand on pulse to see that the game’s get a full grasp on the scope of the project, foresee the catchy, or funny, or scary just as you wanted it, and works super fast. complications and liabilities of the game. Art Direction How to stand out on the market, or how to make all the details look consistent? How colors influence the mood of a player? You guessed it: our art director will be responsible that your game not only looks good, but feels right.