Alexander Malden, Governance Officer, Natural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Energy 2012 Conference & Exhibition

GLOBAL 12 ENERGY 20 29/30/31 OCTOBER 2012 HOTEL PRESIDENT WILSON Global Energy Geneva 2012 Where the oil & gas trade meets...with key participation of Cargill, Gunvor, Lundin, Lukoil, Mercuria, Socar, Trafigura To register: www.globalenergygeneva.com GLOBAL 12 ENERGY 20 GLOBAL ENERGY 2012 CONFERENCE & EXHIBITION 29/30/31 October 2012, Hotel President Wilson, Geneva T: +41 (0) 22 321 74 80 | F: +41 (0) 22 321 74 82 | E: [email protected] | www.globalenergygeneva.com About Global Energy 2012 The oil and gas trade is critical to the global economy and the effect of energy prices and trade is more profound than for any other traded commodity. Global Energy is a trade show, conference and exhibition unique to Geneva. Global Energy 2012 is being held on October 29/30/31 at the prestigious Hotel President Wilson in the heart of Geneva. The event brings together energy traders, banks, policymakers, delivering important keynote speeches and panel debates. Global Energy 2012 takes place during an important week in the Geneva commodities trade calendar. It will be attended by a “who’s who” in oil and gas in Switzerland and abroad. Who will attend Global Energy 2012? Major international oil & gas trading firms Traders from small and medium-sized firms throughout the globe Leaders in the Swiss energy trade community Upstream oil and gas majors – interested in the global S&D of oil and gas Oil and gas investors, including family offices and private banks Trade financiers specialising in oil and gas Professional firms: lawyers, advisory/management -

Redstone Commodity Update Q3

Welcome to the Redstone Commodity Update 2020: Q3 Welcome to the Redstone Commodity Moves Update Q3 2020, another quarter in a year that has been strongly defined by the pandemic. Overall recruitment levels across the board are still down, although we have seen some pockets of hiring intent. There appears to be a general acknowledgement across all market segments that growth must still be encouraged and planned for, this has taken the form in some quite senior / structural moves. The types of hires witnessed tend to pre-empt more mid-junior levels hires within the same companies in following quarters, which leaves us predicting a stronger than expected finish to Q4 2020 and start to Q1 2021 than we had previously planned for coming out of Q2. The highest volume of moves tracked fell to the energy markets, notably, within power and gas and not within the traditional oil focused roles, overall, we are starting to see greater progress towards carbon neutrality targets. Banks such as ABN, BNP and SocGen have all reduced / pulled out providing commodity trade finance, we can expect competition for the acquiring of finance lines to heat up in the coming months until either new lenders step into the market or more traditional lenders swallow up much of the market. We must also be aware of the potential impact of the US elections on global trade as countries such as Great Britain and China (amongst others) await the outcome of the impending election. Many national trade strategies and corporate investment strategies will hinge on this result in a way that no previous election has. -

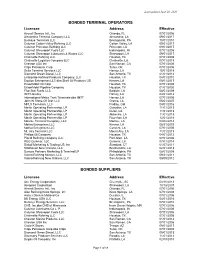

Bonded Terminal Operators

Last updated June 26, 2020 BONDED TERMINAL OPERATORS Licensee Address Effective Aircraft Service Intl., Inc Orlando, FL 07/01/2006 Alexandria Terminal Company LLC Alexandria, LA 09/01/2017 Buckeye Terminals LLC Breinigsville, PA 10/01/2010 Calumet Cotton Valley Refining LLC Cotton Valley, LA 09/01/2017 Calumet Princeton Refining LLC Princeton, LA 09/01/2017 Calumet Shreveport Fuels LLC Indianapolis, IN 07/01/2006 Calumet Shreveport Lubricants & Waxes LLC Shreveport, LA 09/01/2017 Chalmette Refining LLC Houston, TX 07/01/2006 Chalmette Logistics Company LLC Chalmette, LA 07/01/2018 Chevron USA Inc San Ramon, CA 07/01/2006 Citgo Petroleum Corp Tulsa, OK 07/01/2006 Delta Terminal Services LLC Harvey, LA 10/01/2018 Diamond Green Diesel, LLC San Antonio, TX 01/01/2014 Enterprise Refined Products Company, LLC Houston, TX 04/01/2010 Equilon Enterprises LLC dba Shell Oil Products US Kenner, LA 05/01/2017 ExxonMobil Oil Corp Houston, TX 07/01/2006 ExxonMobil Pipeline Company Houston, TX 01/01/2020 Five Star Fuels, LLC Baldwin, LA 08/01/2009 IMTT-Gretna Harvey, LA 04/01/2012 International-Matex Tank Terminals dba IMTT Harvey, LA 07/01/2006 John W Stone Oil Dist, LLC Gretna, LA 05/01/2007 MPLX Terminals, LLC Findlay, OH 04/01/2016 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Gueydan, LA 11/01/2013 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Dulac, LA 11/01/2013 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Abbeville, LA 11/01/2013 Martin Operating Partnership, LP Fourchon, LA 12/01/2016 Monroe Terminal Company, LLC Monroe, LA 04/08/2014 Motiva Enterprises LLC Kenner, LA 08/21/2009 Motiva Enterprises LLC Convent, LA 07/01/2006 Mt. -

Amici Brief File Stamped 020718(Pdf)

Case 17-2233, Document 173-2, 02/07/2018, 2231672, Page1 of 39 17-2233 IN THE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT >> >> PRIME INTERNATIONAL TRADING LTD., ON BEHALF OF ITSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, WHITE OAKS FUND LP, ON BEHALF OF ITSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, KEVIN MCDONNELL, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED,ANTHONY INSINGA, AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, ROBERT MICHIELS, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, JOHN DEVIVO, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, NEIL TAYLOR, AARON SCHINDLER, PORT 22, LLC, ATLANTIC TRADING USA LLC, XAVIER LAURENS, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, Plaintiffs-Appellants, (caption continued on inside cover) On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York BRIEF FOR THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE SECURITIES INDUSTRY AND FINANCIAL MARKETS ASSOCIATION, THE INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, AND THE FUTURES INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES AND AFFIRMANCE GEORGE T. CONWAY III WACHTELL, LIPTON, ROSEN & KATZ 51 West 52nd Street New York, New York 10019 (212) 403–1000 Attorneys for Amici Curiae Case 17-2233, Document 173-2, 02/07/2018, 2231672, Page2 of 39 MICHAEL SEVY, ON BEHALF OF HIMSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, GREGORY H. SMITH, INDIVIDUALLY AND ON BEHALF OF ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, PATRICIA BENVENUTO, ON BEHALF OF HERSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMI- -

2013 Financial and Operating Review

Financial & Operating Review 2 013 Financial & Operating Summary 1 Delivering Profitable Growth 3 Global Operations 14 Upstream 16 Downstream 58 Chemical 72 Financial Information 82 Frequently Used Terms 90 Index 94 General Information 95 COVER PHOTO: Liquefied natural gas (LNG) produced at our joint ventures with Qatar Petroleum is transported to global markets at constant temperature and pressure by dedicated carriers designed and built to meet the most rigorous safety standards. Statements of future events or conditions in this report, including projections, targets, expectations, estimates, and business plans, are forward-looking statements. Actual future results, including demand growth and energy mix; capacity growth; the impact of new technologies; capital expenditures; project plans, dates, costs, and capacities; resource additions, production rates, and resource recoveries; efficiency gains; cost savings; product sales; and financial results could differ materially due to, for example, changes in oil and gas prices or other market conditions affecting the oil and gas industry; reservoir performance; timely completion of development projects; war and other political or security disturbances; changes in law or government regulation; the actions of competitors and customers; unexpected technological developments; general economic conditions, including the occurrence and duration of economic recessions; the outcome of commercial negotiations; unforeseen technical difficulties; unanticipated operational disruptions; and other factors discussed in this report and in Item 1A of ExxonMobil’s most recent Form 10-K. Definitions of certain financial and operating measures and other terms used in this report are contained in the section titled “Frequently Used Terms” on pages 90 through 93. In the case of financial measures, the definitions also include information required by SEC Regulation G. -

Oil Producers Eye Asia As Western Demand Falters

Oil Producers Eye Asia As Western Demand Falters SPECIAL PDF REPORT SEPTEMBER 2011 An oil rig lights up Cape Town harbour as the sun sets, August 6, 2011. REUTERS/Mike Hutchings Oil price volatility a concern for Asia Indian Oil bars Vitol from tenders-sources Two reasons why Asia's still thirsty for crude: Clyde Russell Iran imports 4-5 cargoes of gasoline per month-sources Litasco 2011 revenue to rise 10 pct -CEO Iran restores fuel oil export vols from Oct COMMODITIESOIL PRODUCERS SHIVER EYE ASIA AFTER AS WESTERNU.S. CREDIT DEMAND DOWNGRADE FALTERS SEPTEMBER AUGUST 20112011 Oil price volatility a concern for Asia SINGAPORE, Sept 8 (Reuters) - il traders have been the only beneficiaries from this year's sharp swings in energy prices, but even they have been caught off guard at times, falling prey to geopolitics and wider financial market risk appetite swings. That sums up reflections at Singapore's Asia Pacific Petroleum Conference (APPEC) this week, where oil traders, O company executives and business leaders gathered to discuss an increasingly turbulent and volatile trading envi- ronment. Three years on from the deepest recession since the Great Depression, oil producers and trading firms continue to look to Asia as the saviour for energy markets, while Europe and the U.S. struggle to sustain an economic recovery. This tension has made oil markets the most volatile since 2009, complicating trading strategies and giving trading houses an overdose of the price fluctuations they normally thrive on. "It's too much volatility and sometimes it's not easy to develop trading strategies," said Tony Nunan, a risk manager with To- kyo-based Mitsubishi Corp on the sidelines of the conference. -

World Oil Production and Peaking Outlook.Pdf

Peak Oil Netherlands Foundation (PONL) was founded in May 2005 by a group of citizens who are concerned about the effects of a premature peak in oil and other fossil fuels production. The main aims of PONL are to carry out research and to raise awareness with respect to the depletion of non-renewable energy sources. PONL currently relies on volunteers for its activities. To safeguard its independency, PONL does not accept donations from companies involved in the development of either fossil fuels or alternative sources. The author of this report, Rembrandt Koppelaar, would like to thank the editors of this report, the other people in the Peak Oil Netherlands Foundation for their work, peakoil.com & the oildrum community, C. Campbell for raising the peakoil issue since the early days, R. Heinberg for providing the first Peak Oil book the author did read, J. Laherrère for his splendid papers, M. Simmons for raising awareness regarding peakoil to new heights and writing his book, M. Lynch for his fresh insights regarding peakoil, C. Skrebowksi and CERA for making their oil project reports and last but certainly not least his family from whom he has learned a considerable amount . © 2005 Peak Oil Netherlands Foundation. All rights reserved. Reproduction for non-commercial purposes is allowed. Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 - GLOSSARY OF TERMS ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Royal Dutch Shell and Its Sustainability Troubles

Royal Dutch Shell and its sustainability troubles Background report to the Erratum of Shell's Annual Report 2010 Albert ten Kate May 2011 1 Colophon Title: Royal Dutch Shell and its sustainability troubles Background report to the Erratum of Shell's Annual Report 2010 May 2011. This report is made on behalf of Milieudefensie (Friends of the Earth Netherlands) Author: Albert ten Kate, free-lance researcher corporate social responsibility Pesthuislaan 61 1054 RH Amsterdam phone: (+31)(0)20 489 29 88 mobile: (+31)(0)6 185 68 354 e-mail: [email protected] 2 Contents Introduction 4 Methodology 5 Cases: 1. Muddling through in Nigeria 6 1a) oil spills 1b) primitive gas flaring 1c) conflict and corruption 2. Denial of Brazilian pesticide diseases 14 3. Mining the Canadian tar sands 17 4. The bitter taste of Brazil's sugarcane 20 4a) sourcing sugarcane from occupiers of indigenous land 4b) bad labour conditions sugarcane harvesters 4c) massive monoculture land use 5. Fracking unconventional gas 29 6. Climate change, a business case? 35 7. Interfering with politics 38 8. Drilling plans Alaska’s Arctic Ocean 42 9. Sakhalin: the last 130 Western Gray Whales 45 10. The risky Kashagan oil field 47 11. A toxic legacy in Curaçao 49 12. Philippines: an oil depot amidst a crowd of people 52 3 Introduction Measured in revenue, Royal Dutch Shell is one of the biggest companies in the world. According to its annual report of 2010, its revenue amounted to USD 368 billion in 2010. Shell produces oil and gas in 30 countries, spread over the world. -

Redstone Commodity Update Q4 2020

Welcome to the Redstone Commodity Update 2020: Q4 Welcome to the Redstone Commodity Moves Update Q4 2020, a very interesting period to report on as Redstone witnessed the busiest quarter of the year so far. This is exactly the opposite to what we have witnessed in previous years, the stronger than usual recruitment drive was very much spear headed by a particularly strong showing in the energy space which in turn was led by energy recruitment activity within the EMEA region which we shall cover below. Overall EMEA saw the largest volume of moves in each of the covered sections with the Americas outperforming Asia consistently outside of the Shipping and Bunker space. Overall as we enter 2021 right across the board commodities markets seem to be entering a bullish period with talk of a new super cycle driven by green led commodities and energy. The early signs for 2021 from a recruitment standpoint seem quite positive with many companies who held back last year making early approaches for recruitment projects, many buoyed by the rollout of various Covid-19 vaccines. The certainty around Brexit and the US election allows people to make their plans accordingly with the remaining ongoing issues (such disruption in the US relating to fallout from the election and a serious uptick in Corona cases throughout the western world / new strains etc) seemingly not putting investors off, as at least in the medium term, we can see the light at the end of the tunnel. Noteworthy Energy Talent Moves EMEA saw the greatest volume of moves in Q4 2020 further extending the volumes previously witnessed in terms of both total number of moves reported and as a percentage share of total moves tracked, within this we can see a particularly strong performance for all things power, gas or LNG related, as European power and gas markets provide ROI’s that are too attractive to ignore. -

Chapter 11 ) WHITING PETROLEUM CORPORATION, ) Case No

Case 20-32021 Document 280 Filed in TXSB on 05/06/20 Page 1 of 123 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) WHITING PETROLEUM CORPORATION, ) Case No. 20-32021 (DRJ) et al.,1 ) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) GLOBAL NOTES AND STATEMENT OF LIMITATIONS, METHODOLOGIES, AND DISCLAIMERS REGARDING THE DEBTORS’ SCHEDULES OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES AND STATEMENTS OF FINANCIAL AFFAIRS The Schedules of Assets and Liabilities (collectively with attachments, the “Schedules”) and the Statements of Financial Affairs (collectively with attachments, the “Statements,” and together with the Schedules, the “Schedules and Statements”), filed by the above-captioned debtors and debtors in possession (collectively, the “Debtors”), were prepared pursuant to section 521 of title 11 of the United States Code (the “Bankruptcy Code”) and rule 1007 of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure (the “Bankruptcy Rules”) by the Debtors’ management, with the assistance of the Debtors’ advisors, and are unaudited. These Global Notes and Statement of Limitations, Methodologies, and Disclaimers Regarding the Debtors’ Schedules of Assets and Liabilities and Statements of Financial Affairs (the “Global Notes”) are incorporated by reference in, and comprise an integral part of, each Debtor’s respective Schedules and Statements, and should be referred to and considered in connection with any review of the Schedules and Statements. While the Debtors’ management has made reasonable efforts to ensure that the Schedules and Statements are as accurate and complete as possible under the circumstances, based on information that was available at the time of preparation, inadvertent errors, inaccuracies, or omissions may have occurred or the Debtors may discover subsequent information that requires material changes to the Schedules and Statements. -

17-2233, Document 114, 11/01/2017, 2162193, Page1 of 93 RECORD NO

Case 17-2233, Document 114, 11/01/2017, 2162193, Page1 of 93 RECORD NO. 17-2233 In The United States Court of Appeals For The Second Circuit PRIME INTERNATIONAL TRADING, LTD., ON BEHALF OF ITSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, WHITE OAKS FUND LP, ON BEHALF OF ITSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, KEVIN MCDONNELL, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, ANTHONY INSINGA, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, ROBERT MICHIELS, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, JOHN DEVIVO, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, NEIL TAYLOR, AARON SCHINDLER, PORT 22,LLC, ATLANTIC TRADING USA, LLC, XAVIER LAURENS, ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, Plaintiffs – Appellants, MICHAEL SEVY, ON BEHALF OF HIMSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED,, GREGORY H. SMITH, INDIVIDUALLY AND ON BEHALF OF ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, PATRICIA BENVENUTO, ON BEHALF OF HERSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, DAVID HARTER, ON BEHALF OF HIMSELF AND OTHER SIMILARLY SITUATED PLAINTIFFS, MELISSINOS EUPATRID LP, BEHALF OF ITSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, FTC CAPITAL GMBH, ON BEHALF OF ITSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, WILLIAM KARKUT, CHRISTOPHER CHARTIER, ON BEHALF OF HIMSELF AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, PRAETOR CAPITAL CAYMAN LTD., ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, PRAETOR CAPITAL MANAGEMENT LTD., ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, PRAETOR VII FUTURES AND OPTIONS MASTER FUND LTD., ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, PRAETOR VII FUTURES & OPTIONS FUND LTD., ON BEHALF OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY SITUATED, Plaintiffs, v. -

Nigeria's Oil and Gas Revenues

Briefing December 2017 Nigeria’s Oil and Gas Revenues: Insights From New Company Disclosures Alexander Malden Nigeria is one of the largest and oldest oil producers in Africa, with over 50 years of commercial extractive activity. Until recently, however, citizens within the country have not had sufficient information to hold companies or government entities accountable for billions of dollars of oil and gas revenues, nor to begin to assess the costs, benefits and management of the country’s extractive activities. Box 1. Summary of European and Canadian mandatory disclosure laws Which companies must Oil, gas or mining companies1 registered in or listed on a regulated stock disclose? exchange in Canada, the European Union or European Economic Area.2 What must they Payments made to governments (including state owned enterprises) in disclose? relation to extractive activities. Payments should be attributed to projects where applicable.3 1. Production entitlements 2. Taxes (on income, production or profits) 3. Royalties 4. Dividends 5. Signature, discovery and production bonuses 6. License fees 7. Payments for infrastructure improvements What is the threshold Single, or series of, payments that amount to EUR 100,000 in the EU/EEA for payment reporting? or CAD 100,000 in Canada. When must they EU. The date of the first required report from a company depends on when disclose? the EU Member State enacted the relevant provisions of the European Accounting and Transparency Directives.4 Canada. The Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act came into force on 1 June 2015 and applies to any financial year starting after this date. Companies have 150 days after the end of their financial year to file their Payments to Governments Report.