Roger Bacon (C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Prolongation of Life in Early Modern English Literature and Culture, with Emphasis on Francis Bacon

THE PROLONGATION OF LIFE IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH LITERATURE AND CULTURE, WITH EMPHASIS ON FRANCIS BACON ROGER MARCUS JACKSON A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Dr. Reid Barbour Dr. Mary Floyd-Wilson Dr. Darryl Gless Dr. James O‘Hara Dr. Jessica Wolfe ©2010 Roger Marcus Jackson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ROGER MARCUS JACKSON: The Prolongation of Life in Early Modern English Literature and Culture (Under the direction of Reid Barbour) Drawing upon early modern texts of poetry, theology, and natural philosophy written in England and the continent, this dissertation explores the intellectual traditions inherent in Renaissance discourses addressing the prolongation of life. It is organized around two nodal questions: Can life be prolonged? Should it be prolonged? The project hinges upon Francis Bacon (1561-1626), for whom the prolongation of life in the sense of a longer human lifespan serves as the loftiest goal of modern experimental science. Addressing the first question, Part One illustrates the texture and diversity of early modern theories of senescence and medical treatments against the ―disease‖ of old age promoted by Galen, Avicenna, medieval theologians, Jean Fernel, Marsilio Ficino, and Paracelsus. Part Two then demonstrates that Bacon‘s theory of senescence and corresponding therapies nevertheless differ from those of his predecessors and contemporaries in three regards: their attempt to isolate senescence from disease, their postulation of senescence as a process based on universal structures and actions of matter, and their deferral to further experiment for elucidation. -

Some Thoughts About Natural Law

Some Thoughts About Natural Law Phflip E. Johnsont My first task is to define the subject. When I use the term "natural" law, I am distinguishing the category from other kinds of law such as positive law, divine law, or scientific law. When we discuss positive law, we look to materials like legislation, judicial opinions, and scholarly anal- ysis of these materials. If we speak of divine law, we ask if there are any knowable commands from God. If we look for scientific law, we conduct experiments, or make observations and calculations, in order to come to objectively verifiable knowledge about the material world. Natural law-as I will be using the term in this essay-refers to a method that we employ to judge what the principles of individual moral- ity or positive law ought to be. The natural law philosopher aspires to make these judgments on the basis of reason and human nature without invoking divine revelation or prophetic inspiration. Natural law so defined is a category much broader than any particular theory of natural law. One can believe in the existence of natural law without agreeing with the particular systems of natural law advocates like Aristotle or Aquinas. I am describing a way of thinking, not a particular theory. In the broad sense in which I am using the term, therefore, anyone who attempts to found concepts of justice upon reason and human nature engages in natural law philosophy. Contemporary philosophical systems based on feminism, wealth maximization, neutral conversation, liberal equality, or libertarianism are natural law philosophies. -

Scientific Explanation

Scientific Explanation Michael Strevens For the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy, second edition The three cardinal aims of science are prediction, control, and expla- nation; but the greatest of these is explanation. Also the most inscrutable: prediction aims at truth, and control at happiness, and insofar as we have some independent grasp of these notions, we can evaluate science’s strate- gies of prediction and control from the outside. Explanation, by contrast, aims at scientific understanding, a good intrinsic to science and therefore something that it seems we can only look to science itself to explicate. Philosophers have wondered whether science might be better off aban- doning the pursuit of explanation. Duhem (1954), among others, argued that explanatory knowledge would have to be a kind of knowledge so ex- alted as to be forever beyond the reach of ordinary scientific inquiry: it would have to be knowledge of the essential natures of things, something that neo-Kantians, empiricists, and practical men of science could all agree was neither possible nor perhaps even desirable. Everything changed when Hempel formulated his dn account of ex- planation. In accordance with the observation above, that our only clue to the nature of explanatory knowledge is science’s own explanatory prac- tice, Hempel proposed simply to describe what kind of things scientists ten- dered when they claimed to have an explanation, without asking whether such things were capable of providing “true understanding”. Since Hempel, the philosophy of scientific explanation has proceeded in this humble vein, 1 seeming more like a sociology of scientific practice than an inquiry into a set of transcendent norms. -

Two Concepts of Law of Nature

Prolegomena 12 (2) 2013: 413–442 Two Concepts of Law of Nature BRENDAN SHEA Winona State University, 528 Maceman St. #312, Winona, MN, 59987, USA [email protected] ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE / RECEIVED: 04–12–12 ACCEPTED: 23–06–13 ABSTRACT: I argue that there are at least two concepts of law of nature worthy of philosophical interest: strong law and weak law . Strong laws are the laws in- vestigated by fundamental physics, while weak laws feature prominently in the “special sciences” and in a variety of non-scientific contexts. In the first section, I clarify my methodology, which has to do with arguing about concepts. In the next section, I offer a detailed description of strong laws, which I claim satisfy four criteria: (1) If it is a strong law that L then it also true that L; (2) strong laws would continue to be true, were the world to be different in some physically possible way; (3) strong laws do not depend on context or human interest; (4) strong laws feature in scientific explanations but cannot be scientifically explained. I then spell out some philosophical consequences: (1) is incompatible with Cartwright’s contention that “laws lie” (2) with Lewis’s “best-system” account of laws, and (3) with contextualism about laws. In the final section, I argue that weak laws are distinguished by (approximately) meeting some but not all of these criteria. I provide a preliminary account of the scientific value of weak laws, and argue that they cannot plausibly be understood as ceteris paribus laws. KEY WORDS: Contextualism, counterfactuals, David Lewis, laws of nature, Nancy Cartwright, physical necessity. -

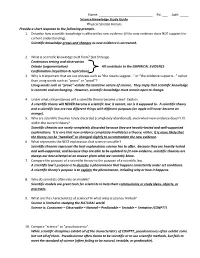

Ast#: ___Science Knowledge Study Guide Physical

Name: ______________________________ Pd: ___ Ast#: _____ Science Knowledge Study Guide Physical Science Honors Provide a short response to the following prompts. 1. Describe how scientific knowledge is affected by new evidence (if the new evidence does NOT support the current understanding). Scientific knowledge grows and changes as new evidence is uncovered. 2. What is scientific knowledge built from? (list 3 things) Continuous testing and observation Debate (argumentation) All contribute to the EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE Confirmation (repetition & replication) 3. Why is it important that we use phrases such as “the results suggest…” or “the evidence supports…” rather than using words such as “prove” or “proof”? Using words such as “prove” violate the tentative nature of science. They imply that scientific knowledge is concrete and unchanging. However, scientific knowledge must remain open to change. 4. Under what circumstances will a scientific theory become a law? Explain. A scientific theory will NEVER become a scientific law; it cannot, nor is it supposed to. A scientific theory and a scientific law are two different things with different purposes (an apple will never become an orange). 5. Why are scientific theories rarely discarded (completely abandoned), even when new evidence doesn’t fit within the current theory? Scientific theories are rarely completely discarded because they are heavily-tested and well-supported explanations. It is rare that new evidence completely invalidates a theory; rather, it is more likely that the theory can be “tweaked” or changed slightly to accommodate the new evidence. 6. What represents the BEST explanation that science can offer? Scientific theories represent the best explanations science has to offer. -

THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD and the LAW by Bemvam L

Hastings Law Journal Volume 19 | Issue 1 Article 7 1-1967 The cS ientific ethoM d and the Law Bernard L. Diamond Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bernard L. Diamond, The Scientific etM hod and the Law, 19 Hastings L.J. 179 (1967). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol19/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD AND THE LAW By BEmVAm L. DIivmN* WHEN I was an adolescent, one of the major influences which determined my choice of medicine as a career was a fascinating book entitled Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine. This huge volume, originally published in 1897, is a museum of pictures and lurid de- scriptions of human monstrosities and abnormalities of all kinds, many with sexual overtones of a kind which would especially appeal to a morbid adolescent. I never thought, at the time I first read this book, that some day, I too, would be an anomaly and curiosity of medicine. But indeed I am, for I stand before you here as a most curious and anomalous individual: a physician, psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and (I hope) a scientist, who also happens to be a professor of law. But I am not a lawyer, nor in any way trained in the law; hence, the anomaly. The curious question is, of course, why should a non-lawyer physician and scientist, like myself, be on the faculty of a reputable law school. -

Rules of Law, Laws of Science

Rules of Law, Laws of Science Wai Chee Dimock* My Essay is a response to legal realism,' to its well-known arguments against "rules of law." Legal realism, seeing itself as an empirical practice, was not convinced that there could be any set of rules, formalized on the grounds of logic, that would have a clear determinative power on the course of legal action or, more narrowly, on the outcome of litigated cases. The decisions made inside the courtroom-the mental processes of judges and juries-are supposedly guided by rules. Realists argued that they are actually guided by a combination of factors, some social and some idiosyncratic, harnessed to no set protocol. They are not subject to the generalizability and predictability that legal rules presuppose. That very presupposition, realists said, creates a gap, a vexing lack of correspondence, between the language of the law and the world it purports to describe. As a formal system, law operates as a propositional universe made up of highly technical terms--estoppel, surety, laches, due process, and others-accompanied by a set of rules governing their operation. Law is essentially definitional in this sense: It comes into being through the specialized meanings of words. The logical relations between these specialized meanings give it an internal order, a way to classify cases into actionable categories. These categories, because they are definitionally derived, are answerable only to their internal logic, not to the specific features of actual disputes. They capture those specific features only imperfectly, sometimes not at all. They are integral and unassailable, but hollowly so. -

Early Modern Philosophy of Technology: Bacon and Descartes

Early Modern Philosophy of Technology: Bacon and Descartes By Robert Arnăutu Submitted to Central European University Department of Philosophy In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Supervisor: Professor Hanoch Ben-Yami CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013 Copyright notice I hereby declare that this dissertation contains no materials accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions of higher education. Also, I declare that this dissertation contains no material previously written and/or published by any other person, except where appropriate acknowledgement has been made in the form of bibliographic reference. Robert Arnăutu June 2013 CEU eTD Collection i Abstract The contemporary understanding of technology is indebted to Bacon and Descartes, who challenged the pre-modern conceptions regarding useful material production. Although the production of artefacts has been a constant activity of humans since the dawn of history, the Ancient world tended to disvalue it, considering it a lower endeavour that aims to satisfy ignoble material needs. Technology, according to Ancient Greek thinkers, cannot surpass nature but can only bring small improvements to it; moreover, there is a difference in kind between natural things and technological artefacts; the activity of inventing and producing useful objects is unsuited for the nobility and for free men; there is an irreducible gap between proper knowledge and the production of artefacts. This approach toward technology is completely -

Descartes' Optics

Descartes’ Optics Jeffrey K. McDonough Descartes’ work on optics spanned his entire career and represents a fascinating area of inquiry. His interest in the study of light is already on display in an intriguing study of refraction from his early notebook, known as the Cogitationes privatae, dating from 1619 to 1621 (AT X 242-3). Optics figures centrally in Descartes’ The World, or Treatise on Light, written between 1629 and 1633, as well as, of course, in his Dioptrics published in 1637. It also, however, plays important roles in the three essays published together with the Dioptrics, namely, the Discourse on Method, the Geometry, and the Meteorology, and many of Descartes’ conclusions concerning light from these earlier works persist with little substantive modification into the Principles of Philosophy published in 1644. In what follows, we will look in a brief and general way at Descartes’ understanding of light, his derivations of the two central laws of geometrical optics, and a sampling of the optical phenomena he sought to explain. We will conclude by noting a few of the many ways in which Descartes’ efforts in optics prompted – both through agreement and dissent – further developments in the history of optics. Descartes was a famously systematic philosopher and his thinking about optics is deeply enmeshed with his more general mechanistic physics and cosmology. In the sixth chapter of The Treatise on Light, he asks his readers to imagine a new world “very easy to know, but nevertheless similar to ours” consisting of an indefinite space filled everywhere with “real, perfectly solid” matter, divisible “into as many parts and shapes as we can imagine” (AT XI ix; G 21, fn 40) (AT XI 33-34; G 22-23). -

Introduction to Optics

2.71/2.710 Optics 2.71/2.710 Optics • Instructors: Prof. George Barbastathis Prof. Colin J. R. Sheppard • Assistant Instructor: Dr. Se Baek Oh • Teaching Assistant: José (Pepe) A. Domínguez-Caballero • Admin. Assistant: Kate Anderson Adiana Abdullah • Units: 3-0-9, Prerequisites: 8.02, 18.03, 2.004 • 2.71: meets the Course 2 Restricted Elective requirement • 2.710: H-Level, meets the MS requirement in Design • “gateway” subject for Doctoral Qualifying exam in Optics • MIT lectures (EST): Mo 8-9am, We 7:30-9:30am • NUS lectures (SST): Mo 9-10pm, We 8:30-10:30pm MIT 2.71/2.710 02/06/08 wk1-b- 2 Image of optical coherent tomography removed due to copyright restrictions. Please see: http://www.lightlabimaging.com/image_gallery.php Images from Wikimedia Commons, NASA, and timbobee at Flickr. MIT 2.71/2.710 02/06/08 wk1-b- 3 Natural & artificial imaging systems Image by NIH National Eye Institute. Image by Thomas Bresson at Wikimedia Commons. Image by hyperborea at Flickr. MIT 2.71/2.710 Image by James Jones at Wikimedia Commons. 02/06/08 wk1-b- 4 Image removed due to copyright restrictions. Please see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:LukeSkywalkerROTJV2Wallpaper.jpg MIT 2.71/2.710 02/06/08 wk1-b- 5 Class objectives • Cover the fundamental properties of light propagation and interaction with matter under the approximations of geometrical optics and scalar wave optics, emphasizing – physical intuition and underlying mathematical tools – systems approach to analysis and design of optical systems • Application of the physical concepts to topical -

Roger Bacon and the Beginnings of Experimental Science in Britain

FROM THE JAMES LIND LIBRARY Roger Bacon and the beginnings of experimental science in Britain Eric Sidebottom Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, Oxford OX1 3RE, UK Correspondence to: Eric Sidebottom. Email: [email protected] DECLARATIONS Roger Bacon is something of an enigma. He has I am puzzled that RW Southern’s biography of been called many things – ‘Britain’s first scientist’, Grosseteste does not mention Roger Bacon,2 des- Competing interests ‘wonderful doctor’, ‘conjurer’ and ‘magician’. pite the Preface in AC Crombie’s Robert Grosseteste None declared Many of the details of his life are uncertain and and the origins of experimental science, published they have been discussed and argued about by half a century earlier, which states: ‘In the 13thC, Funding scholars for centuries. He is generally thought to the Oxford school, with Robert Grosseteste as its None declared have been born in Ilchester, Somerset, around founder, assumes a paramount importance: the 1214, although some authors have put his date work of this school in fact marks the beginning Ethical approval of birth as late as 1220. There is good evidence of the modern tradition of experimental science’.3 that he was in Paris in 1245 and 1251, but it is What is clear is that Roger Bacon was an Not applicable uncertain if he ever actually studied in Oxford. innovative thinker and a courageous scholar, not Contributorship If he did, he would have met Robert Grosseteste, afraid to challenge current beliefs about philoso- often described as Oxford University’s first phy, science and religion. -

Criminal Responsibility and Causal Determinism J

Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 9 | Issue 1 2016 Criminal Responsibility and Causal Determinism J. G. Moore Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Theory Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons This document is a corrected version of the article originally published in print. To access the original version, follow the link in the Recommended Citation then download the file listed under “Previous Versions." Recommended Citation J. G. Moore, Criminal Responsibility and Causal Determinism, 9 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 043 (2016, corrected 2016). Available at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol9/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Criminal Responsibility and Causal Determinism Cover Page Footnote This document is a corrected version of the article originally published in print. To access the original version, follow the link in the Recommended Citation then download the file listed under “Previous Versions." This article is available in Washington University Jurisprudence Review: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol9/ iss1/6 CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY AND CAUSAL DETERMINISM: CORRECTED VERSION J G MOORE* INTRODUCTION In analytical jurisprudence, determinism has long been seen as a threat to free will, and free will has been considered necessary for criminal responsibility.1 Accordingly, Oliver Wendell Holmes held that if an offender were hereditarily or environmentally determined to offend, then her free will would be reduced, and her responsibility for criminal acts would be correspondingly diminished.2 In this respect, Holmes followed his father, Dr.