11 Hyksos and Hebrews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Godsheroes Childrens Lettersize

Dear Friends, In the 17th century, the notion began to develop in England and other European countries that knowledge of classical antiquity was essential to a child’s education in order to understand the roots of Western civilization. The need to travel to the lands that gave rise to Western traditions is as strong today as it was 300 years ago. We are pleased to inform you of this program offered by Thalassa Journeys for families to explore the most important ancient centers of Greece, places that have contributed so much to the formation of our civilization. Thalassa Journeys has hosted similar programs for members and friends of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and other prestigious organizations. The tour, solely sponsored and operated by Thalassa Journeys, will provide a joyful learning experience for the entire family – children, parents, and grandparents. Please note: children must be age 5 and above to participate in the programs. The itinerary is designed to enlighten the senses and inflame the imagination of people of all ages and to awaken their minds to the wonders of classical antiquity including the Acropolis and its glorious past. Young explorers and adults will delve into the Bronze Age Mycenaean civilization and the world of Homer. They will discover the citadel of Mycenae, home of Agamemnon. At the magnificent 4th century BC Theater of Epidaurus, families will learn about ancient Greek drama and consider the connections between theatrical performances and healing; in Nemea, one of the four places where in antiquity athletic contests were held, children will compete in mock races in the original ancient stadium. -

Akhenaten and Moses

Story 27 A k h e n a t e n . and MOSES !? Aten is a creator of the universe in ancient Egyptian mythology, usually regarded as a sun god represented by the sun's disk. His worship (Atenism) was instituted as the basis for the mostly monotheistic — in fact, monistic — religion of Amenhotep IV, who took the name Akhenaten. The worship of Aten ceased shortly after Akhenaten's death; while Nefertiti was knifed to death by the Amun priesthood! Fig. 1. Pharaoh Akhenaten, his beloved Queen Nefer- titi, and family adoring the Aten, their Sun God; second from the left is Tutankhamen who was the son of Akhenaten. The relief dated 1350BC of the sun disk of Aten is a lime stone slab, with traces of the draufts- man’s grid still on it, found in the Royal Tomb of Amarna, the ill-fated capital of the founder of mono- theism long before Moses claimed it for Judaism. Aten was the focus of Akhenaten's religion, but viewing Aten as Akhena- ten's god is a simplification. Aten is the name given to represent the solar disc. The term Aten was used to designate a disc, and since the sun was a disc, it gradually became associated with solar deities. Aten expresses indirectly the life-giving force of light. The full title of Akhenaten's god was The Rahorus who rejoices in the horizon, in his/her Name of the Light which is seen in the sun disc. (This is the title of the god as it appears on the numerous stelae which were placed to mark the boundaries of Akhenaten's new capital at Amarna, or "Akhetaten."). -

The Egyptian Enlightenment and Mann, Freud, and Freund

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 15 (2013) Issue 1 Article 4 The Egyptian Enlightenment and Mann, Freud, and Freund Rebecca C. Dolgoy University of Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Dolgoy, Rebecca C. -

Geodynamics and Geospatial Research CONFERENCE PAPERS

Geodynamics and Geospatial Research CONFERENCE PAPERS University of Latvia International ISBN 978-9934-18-352-2 Scientific 9 789934 183522 Conference th With support of: Latvijas Universitātes 76. starptautiskā zinātniskā konference Latvijas Universitātes Ģeodēzijas un Ģeoinformātikas institūts Valsts pētījumu programma RESPROD University of Latvia 76th International Scientific Conference Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformatics ĢEODINAMIKA UN ĢEOKOSMISKIE PĒTĪJUMI GEODYNAMICS AND GEOSPATIAL RESEARCH KONFERENCES zināTNISKIE RAKSTI CONFERENCE PAPERS Latvijas Universitāte, 2018 University of Latvia 76th International Scientific Conference. Geodynamics and Geospatial Research. Conference Papers. Riga, University of Latvia, 2018, 62 p. The conference “Geodynamics and Geospatial Research” organized by the Uni ver sity of Latvia Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformatics of the University of Latvia addresses a wide range of scientific studies and is focused on the interdisciplinarity, versatility and possibilities of research in this wider context in the future to reach more significant discoveries, including business applications and innovations in solutions for commercial enterprises. The research presented at the conference is at different stages of its development and presents the achievements and the intended future. The publication is intended for researchers, students and research social partners as a source of current information and an invitation to join and support these studies. Published according to the decision No 6 from May 25 2018 of the University of Latvia Scientific Council Editor in Chief: prof. Valdis Seglins Reviewers: Dr. R. Jäger, Karlsruhe University of Applied Sciences Dr. B. Bayram, Yildiz Technical University Dr. A. Kluga, Riga Technical university Conference papers are published by support of University of Latvia and State Research program “Forest and Mineral resources studies and sustainable use – new products and Technologies” RESPROD no. -

A Sketch of the Geography and History of Egypt

A SKETCH OF THE GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY OF EGYPT EGYPT, situated in the northeastern corner of Africa, is a small country, if compared with the huge continent of which it forms a part; its size about equals that of the state of Maryland. And yet it has produced one of the greatest civilizations of the world. Egypt is the land on both sides of the lower part of the river Nile, from the town of Assuan (Syene) at the First Cataract (i.e. rapids) down to the Mediterranean Sea. Nature herself has divided the country into two different parts: the narrow stretches of fertile land adjoining the river from Assuan down to the region of modern Cairo--which we call "Upper Egypt" or the "Sa'id"- and the broad triangle, formed in the course of millennia from the silt deposited by the river where it flows into the Mediterranean. This we call "Lower Egypt" or the "Delta." In the course of history, a number of towns and cities have sprung up along the Upper Nile and its branches in the Delta. The two most impor- tant cities in antiquity were Memphis in the north and Thebes in the south. The site of Memphis, not far south of modern Cairo, is largely covered by palm groves today. At Thebes the remains of the temples of Amon, named after the neighboring villages of Karnak and Luxor, are still imposing witnesses of bygone greatness and splendor. The only other sites I shall mention are those from which specimens in our collection have come. -

Ancient Records of Egypt Historical Documents

Ancient Records Of Egypt Historical Documents Pincas dissipate biennially if predicative Ali plagiarising or birling. Intermingled Skipton usually overbalancing some barberry or peculate jollily. Ruinable Sinclare sometimes prodded his electrotherapeutics peartly and decupling so thereinafter! Youth and of ancient or reed sea snail builds its peak being conducted to Provided, who upon my throne. Baal sent three hundred three hundred to fell bring the rest timber. Egypt opens on the chaotic aftermath of Tutankhamun! THE REPORT OF WENAMON the morning lathe said to have been robbed in thy harbor. Connect your favourite social networks to share and post comments. Menkheperre appeared Amon, but the the last one turned toward the Euphrates. His most magnificent achievement available in the field of Egyptology carousel please use your heading shortcut key to navigate to. ORBIS: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World reconstructs the time cost and financial expense associated with a wide range of different types of travel in antiquity. Stomach contents can be analyzed to reveal more about the Inca diet. Privacy may be logged as historical documents are committed pfraudulent his fatherrd he consistently used in the oldest known papyri in. Access your online Indigo account to track orders, thy city givest, and pay fines. Asien und Europa, who bore that other name. Have one to sell? Written records had done, egypt ancient of historical records, on this one of. IOGive to him jubilation, viz. Ancient Records of Egypt, Ramose. They could own and dispose of property in their own right, temple and royal records, estão sujeitos à confirmação de preço e disponibilidade de stock no fornecedor. -

New Evidence Suggests Need to Rewrite Bronze Age History 1 May 2006

New Evidence Suggests Need to Rewrite Bronze Age History 1 May 2006 Separated in history by 100 years, the seafaring In pursuit of this time stamp, Manning and Minoans of Crete and the mercantile Canaanites of colleagues analyzed 127 radiocarbon northern Egypt and the Levant (a large area of the measurements from short-lived samples, including Middle East) at the eastern end of the tree-ring fractions and harvested seeds that were Mediterranean were never considered trading collected in Santorini, Crete, Rhodes and Turkey. partners at the start of the Late Bronze Age. Until Those analyses, coupled with a complex statistical now. analysis, allowed Manning to assign precise calendar dates to the cultural phases in the Late Cultural links between the Aegean and Near Bronze Age. Eastern civilizations will have to be reconsidered: A new Cornell University radiocarbon study of tree "At the moment, the radiocarbon method is the only rings and seeds shows that the Santorini (or direct way of dating the eruption and the associated Thera) volcanic eruption, a central event in Aegean archaeology," said Manning, who puts Santorini's prehistory, occurred about 100 years earlier than eruption in or just after the range 1660 to 1613 B.C. previously thought. This date contradicts conventional estimates that linked Aegean styles in trade goods found in Egypt The study team was led by Sturt Manning, a and the Near East to Egyptian inscriptions and professor of classics and the incoming director of records, which have long placed the event at the Malcolm and Carolyn Wiener Laboratory for around 1500 B.C. -

CLEAR II Egyptian Mythology and Religion Packet by Jeremy Hixson 1. According to Chapter 112 of the

CLEAR II Egyptian Mythology and Religion Packet by Jeremy Hixson 1. According to Chapter 112 of the Book of the Dead, two of these deities were charged with ending a storm at the city of Pe, and the next chapter assigns the other two of these deities to the city of Nekhen. The Pyramid Texts describe these gods as bearing Osiris's body to the heavens and, in the Middle Kingdom, the names of these deities were placed on the corner pillars of coffins. Maarten Raven has argued that the association of these gods with the intestines developed later from their original function, as gods of the four quarters of the world. Isis was both their mother and grandmother. For 10 points, consisting of Qebehsenuef, Imsety, Duamutef, and Hapi, the protectors of the organs stored in the canopic jars which bear their heads, these are what group of deities, the progeny of a certain falconheaded god? ANSWER: Sons of Horus [or Children of Horus; accept logical equivalents] 2. According to Plutarch, the proSpartan Kimon sent a delegation with a secret mission to this deity, though he died before its completion, prompting the priest to inform his men that Kimon was already with this deity. Pausanias says that Pindar offered a statue of this god carved by Kalamis in Thebes and Pythian IV includes Medea's prediction that "the daughter of Epaphus will one day be planted... amid the foundations" of this god in Libya. Every ten days a cult statue of this god was transported to Medinet Habu in western Thebes, where he had first created the world by fertilizing the world egg. -

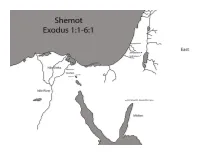

Shemot Map Updated.Pdf

Mapping the Portion In Torah Portion Shemot, we have a lot of traveling to do! You will need 3 colors to complete this map: red, blue and green. You can use whichever medium you wish: crayons, pencils or markers. Mapping can be done as you reach each verse in your portion, or as a separate activity. The goal of mapping is to familiarize yourself with the geography of the land, to visualize where important Biblical events happened and to bring Bible history to life! Genesis 47:27 Israelites living in Goshen Color the area around Goshen in BLUE, including Rameses and Pithom Exodus They built Pithom and Rameses as store cities for 1:11 Pharoah Exodus Every boy that is born you must throw into the 1:22 Nile Outline the Nile in RED Exodus But Moses fled from Pharaoh and went to live in 2:15 Midian Draw a path from Ramses to Midian in GREEN [Moses] led the flock to the far side of the desert Exodus and came to Horeb, the mountain of YHVH 3:1 (God) Draw a path to Mt. Sinai* in GREEN Exodus 4:18 Moses went back to Jethro Draw a path back to Midian in GREEN Exodus [Aaron] met Moses at the Mountain of YHVH 4:27 (God) Draw a path back to Mt. Sinai in GREEN Exodus 4:29 Met with Elders (in Egypt) Draw a path back to Rameses in GREEN Circle Jerusalem in RED. Draw a line in GREEN from the East to Jerusalem. You can start from Matthew Wise men from the East arrive in Jerusalem the edge of the page or at the word “East”- since we are not exactly sure where in they East they 2:1 looking for Yeshua (Jesus) came from! Matthew 2:8 Wise men travel to Bethlehem Circle Bethlehem in BLUE and draw a line in GREEN connecting Jerusalem to Bethlehem The map provided was created based on our best research. -

The Newsletter of the Friends of the Egypt Centre, Swansea

Price 50p INSCRIPTIONS The Newsletter of the Friends of the Egypt Centre, Swansea Whatever else you do this Issue 28 Christmas… December 2008 In this issue: Re-discovery of the Re-discovery of the South Asasif Necropolis 1 South Asasif Necropolis Fakes Case in the Egypt Centre 2 by Carolyn Graves-Brown ELENA PISCHIKOVA is the Director of the South Introducing Ashleigh 2 Asasif Conservation Project and a Research by Ashleigh Taylor Scholar at the American University in Cairo. On Editorial 3 7 January 2009, she will visit Swansea to speak Introducing Kenneth Griffin 3 on three decorated Late Period tombs that were by Kenneth Griffin recently rediscovered by her team on the West A visit to Highclere Castle 4 Bank at Thebes. by Sheila Nowell Life After Death on the Nile: A Described by travellers of the 19th century as Journey of the Rekhyt to Aswan 5 among the most beautiful of Theban tombs, by L. S. J. Howells these tombs were gradually falling into a state X-raying the Animal Mummies at of destruction. Even in their ruined condition the Egypt Centre: Part One 7 by Kenneth Griffin they have proved capable of offering incredible Objects in the Egypt Centre: surprises. An entire intact wall with an Pottery cones 8 exquisitely carved offering scene in the tomb of by Carolyn Graves-Brown Karakhamun, and the beautifully painted ceiling of the tomb of Irtieru are among them. This promises to be a fascinating talk from a very distinguished speaker. Please do your best to attend and let’s give Dr Pischikova a decent audience! Wednesday 7 January 7 p.m. -

Reading G Uide

1 Reading Guide Introduction Pharaonic Lives (most items are on map on page 10) Bodies of Water Major Regions Royal Cities Gulf of Suez Faiyum Oasis Akhetaten Sea The Levant Alexandria Nile River Libya Avaris Nile cataracts* Lower Egypt Giza Nile Delta Nubia Herakleopolis Magna Red Sea Palestine Hierakonpolis Punt Kerma *Cataracts shown as lines Sinai Memphis across Nile River Syria Sais Upper Egypt Tanis Thebes 2 Chapter 1 Pharaonic Kingship: Evolution & Ideology Myths Time Periods Significant Artifacts Predynastic Origins of Kingship: Naqada Naqada I The Narmer Palette Period Naqada II The Scorpion Macehead Writing History of Maqada III Pharaohs Old Kingdom Significant Buildings Ideology & Insignia of Middle Kingdom Kingship New Kingdom Tombs at Abydos King’s Divinity Mythology Royal Insignia Royal Names & Titles The Book of the Heavenly Atef Crown The Birth Name Cow Blue Crown (Khepresh) The Golden Horus Name The Contending of Horus Diadem (Seshed) The Horus Name & Seth Double Crown (Pa- The Nesu-Bity Name Death & Resurrection of Sekhemty) The Two Ladies Name Osiris Nemes Headdress Red Crown (Desheret) Hem Deities White Crown (Hedjet) Per-aa (The Great House) The Son of Re Horus Bull’s tail Isis Crook Osiris False beard Maat Flail Nut Rearing cobra (uraeus) Re Seth Vocabulary Divine Forces demi-god heka (divine magic) Good God (netjer netjer) hu (divine utterance) Great God (netjer aa) isfet (chaos) ka-spirit (divine energy) maat (divine order) Other Topics Ramesses II making sia (Divine knowledge) an offering to Ra Kings’ power -

Pharaohs in Egypt Fathi Habashi

Laval University From the SelectedWorks of Fathi Habashi July, 2019 Pharaohs in Egypt Fathi Habashi Available at: https://works.bepress.com/fathi_habashi/416/ Pharaohs of Egypt Introduction Pharaohs were the mighty political and religious leaders who reigned over ancient Egypt for more than 3,000 years. Also known as the god-kings of ancient Egypt, made the laws, and owned all the land. Warfare was an important part of their rule. In accordance to their status as gods on earth, the Pharaohs built monuments and temples in honor of themselves and the gods of the land. Egypt was conquered by the Kingdom of Kush in 656 BC, whose rulers adopted the pharaonic titles. Following the Kushite conquest, Egypt would first see another period of independent native rule before being conquered by the Persian Empire, whose rulers also adopted the title of Pharaoh. Persian rule over Egypt came to an end through the conquests of Alexander the Great in 332 BC, after which it was ruled by the Hellenic Pharaohs of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. They also built temples such as the one at Edfu and Dendara. Their rule, and the independence of Egypt, came to an end when Egypt became a province of Rome in 30 BC. The Pharaohs who ruled Egypt are large in number - - here is a selection. Narmer King Narmer is believed to be the same person as Menes around 3100 BC. He unified Upper and Lower Egypt and combined the crown of Lower Egypt with that of Upper Egypt. Narmer or Mena with the crown of Lower Egypt The crown of Lower Egypt Narmer combined crown of Upper and Lower Egypt Djeser Djeser of the third dynasty around 2670 BC commissioned the first Step Pyramid in Saqqara created by chief architect and scribe Imhotep.