Living on the Bark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bark Anatomy and Cell Size Variation in Quercus Faginea

Turkish Journal of Botany Turk J Bot (2013) 37: 561-570 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/botany/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1201-54 Bark anatomy and cell size variation in Quercus faginea 1,2, 2 2 2 Teresa QUILHÓ *, Vicelina SOUSA , Fatima TAVARES , Helena PEREIRA 1 Centre of Forests and Forest Products, Tropical Research Institute, Tapada da Ajuda, 1347-017 Lisbon, Portugal 2 Centre of Forestry Research, School of Agronomy, Technical University of Lisbon, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisbon, Portugal Received: 30.01.2012 Accepted: 27.09.2012 Published Online: 15.05.2013 Printed: 30.05.2013 Abstract: The bark structure of Quercus faginea Lam. in trees 30–60 years old grown in Portugal is described. The rhytidome consists of 3–5 sequential periderms alternating with secondary phloem. The phellem is composed of 2–5 layers of cells with thin suberised walls and narrow (1–3 seriate) tangential band of lignified thick-walled cells. The phelloderm is thin (2–3 seriate). Secondary phloem is formed by a few tangential bands of fibres alternating with bands of sieve elements and axial parenchyma. Formation of conspicuous sclereids and the dilatation growth (proliferation and enlargement of parenchyma cells) affect the bark structure. Fused phloem rays give rise to broad rays. Crystals and druses were mostly seen in dilated axial parenchyma cells. Bark thickness, sieve tube element length, and secondary phloem fibre wall thickness decreased with tree height. The sieve tube width did not follow any regular trend. In general, the fibre length had a small increase toward breast height, followed by a decrease towards the top. -

Annotated Check List and Host Index Arizona Wood

Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood-Rotting Fungi Item Type text; Book Authors Gilbertson, R. L.; Martin, K. J.; Lindsey, J. P. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 28/09/2021 02:18:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/602154 Annotated Check List and Host Index for Arizona Wood - Rotting Fungi Technical Bulletin 209 Agricultural Experiment Station The University of Arizona Tucson AÏfJ\fOTA TED CHECK LI5T aid HOST INDEX ford ARIZONA WOOD- ROTTlNg FUNGI /. L. GILßERTSON K.T IyIARTiN Z J. P, LINDSEY3 PRDFE550I of PLANT PATHOLOgY 2GRADUATE ASSISTANT in I?ESEARCI-4 36FZADAATE A5 S /STANT'" TEACHING Z z l'9 FR5 1974- INTRODUCTION flora similar to that of the Gulf Coast and the southeastern United States is found. Here the major tree species include hardwoods such as Arizona is characterized by a wide variety of Arizona sycamore, Arizona black walnut, oaks, ecological zones from Sonoran Desert to alpine velvet ash, Fremont cottonwood, willows, and tundra. This environmental diversity has resulted mesquite. Some conifers, including Chihuahua pine, in a rich flora of woody plants in the state. De- Apache pine, pinyons, junipers, and Arizona cypress tailed accounts of the vegetation of Arizona have also occur in association with these hardwoods. appeared in a number of publications, including Arizona fungi typical of the southeastern flora those of Benson and Darrow (1954), Nichol (1952), include Fomitopsis ulmaria, Donkia pulcherrima, Kearney and Peebles (1969), Shreve and Wiggins Tyromyces palustris, Lopharia crassa, Inonotus (1964), Lowe (1972), and Hastings et al. -

Taxon Order Family Scientific Name Common Name Non-Native No. of Individuals/Abundance Notes Bees Hymenoptera Andrenidae Calliop

Taxon Order Family Scientific Name Common Name Non-native No. of individuals/abundance Notes Bees Hymenoptera Andrenidae Calliopsis andreniformis Mining bee 5 Bees Hymenoptera Apidae Apis millifera European honey bee X 20 Bees Hymenoptera Apidae Bombus griseocollis Brown belted bumble bee 1 Bees Hymenoptera Apidae Bombus impatiens Common eastern bumble bee 12 Bees Hymenoptera Apidae Ceratina calcarata Small carpenter bee 9 Bees Hymenoptera Apidae Ceratina mikmaqi Small carpenter bee 4 Bees Hymenoptera Apidae Ceratina strenua Small carpenter bee 10 Bees Hymenoptera Apidae Melissodes druriella Small carpenter bee 6 Bees Hymenoptera Apidae Xylocopa virginica Eastern carpenter bee 1 Bees Hymenoptera Colletidae Hylaeus affinis masked face bee 6 Bees Hymenoptera Colletidae Hylaeus mesillae masked face bee 3 Bees Hymenoptera Colletidae Hylaeus modestus masked face bee 2 Bees Hymenoptera Halictidae Agapostemon virescens Sweat bee 7 Bees Hymenoptera Halictidae Augochlora pura Sweat bee 1 Bees Hymenoptera Halictidae Augochloropsis metallica metallica Sweat bee 2 Bees Hymenoptera Halictidae Halictus confusus Sweat bee 7 Bees Hymenoptera Halictidae Halictus ligatus Sweat bee 2 Bees Hymenoptera Halictidae Lasioglossum anomalum Sweat bee 1 Bees Hymenoptera Halictidae Lasioglossum ellissiae Sweat bee 1 Bees Hymenoptera Halictidae Lasioglossum laevissimum Sweat bee 1 Bees Hymenoptera Halictidae Lasioglossum platyparium Cuckoo sweat bee 1 Bees Hymenoptera Halictidae Lasioglossum versatum Sweat bee 6 Beetles Coleoptera Carabidae Agonum sp. A ground beetle -

Tree Identification: from Bark and Leaves Or Needles

Tree Identification: from bark and leaves or needles A walk in the woods can be a lot of fun, especially if you bring your kids. How do you get them to come along with you? Tell them this. “Look at the bark on the trees. Can you can find any that look like burnt potato chips, warts, cat scratches, camouflage pants or rippling muscles?” Believe it or not, these are descriptions of different kinds of tree bark. Tree ID from bark:______________________________________________________ Black cherry: The bark looks like burnt potato chips. Hackberry: The bark is bumpy and warty. Ironwood: The bark has long thin strips. With a little imagination, an ironwood can look like it is used as a scratching post by cats. They can also be easily spotted in winter because their light brown dead leaves hang on well past the first snow. Sycamore: A tree with bark that looks like camouflaged pants. The largest tree in Illinois is a sycamore, a majestic 115-foot tree near Springfield. Musclewood: a tree with smooth gray bark covering a trunk with ridges that look like they are rippling muscles. Shagbark hickory: Long strips of shaggy bark peeling at both ends. Cottonwood: Has heavy ridges that make it look like Paul Bunyan’s corduroy pants. Bur oak: Thick and gnarly bark has deep craggy furrows. The corky bark allows it to easily withstand hot forest fires. Tree ID from leaves or needles:________________________________________ Willow Oak: Has elongated leaves similar to those of a willow tree. Red pine: Red has 3 letters; a red pine has groupings of 2-3 prickly needles. -

Tree Pruning: the Basics! Pruning Objectives!

1/12/15! Tree Pruning: The Basics! Pruning Objectives! Improve Plant Health! Safety! Aesthetics! Bess Bronstein! [email protected] Direct Growth! Pruning Trees Increase Flowers & Fruit! Remember-! Leaf, Bud & Branch Arrangement! ! Plants have a genetically predetermined size. Pruning cant solve all problems. So, plant the right plant in the right way in the right place.! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees 1! 1/12/15! One year old MADCap Horse, Ole!! Stem & Buds! Two years old Three years old Internode Maple! Ash! Horsechestnut! Dogwood! Oleaceae! Node Caprifoliaceae! Most plants found in these genera and families have opposite leaf, bud and branch arrangement.! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees One year old Node & Internode! Stem & Buds! Two years old Three years old Internode Node! • Buds, leaves and branches arise here! Bud scale scars - indicates yearly growth Internode! and tree vigor! • Stem area between Node nodes! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees 2! 1/12/15! One year old Stem & Buds! Two years old Dormant Buds! Three years old Internode Bud scale scars - indicates yearly growth and tree vigor! Node Latent bud - inactive lateral buds at nodes! Latent! Adventitious" Adventitious bud! - found in unexpected areas (roots, stems)! Pruning Trees Pruning Trees One year old Epicormic Growth! Stem & Buds! Two years old Three years old Growth from dormant buds, either latent or adventitious. Internode These branches are weakly attached.! Axillary (lateral) bud - found along branches below tips! Bud scale scars - indicates yearly growth and tree vigor! Node -

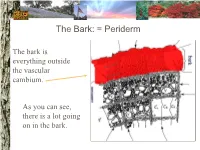

The Bark: = Periderm

The Bark: = Periderm The bark is everything outside the vascular cambium. As you can see, there is a lot going on in the bark. The Bark: periderm: phellogen (cork cambium): The phellogen is the region of cell division that forms the periderm tissues. Phellogen development influences bark appearance. The Bark: periderm: phellem (cork): Phellem replaces the epidermis as the tree increases in girth. Photosynthesis can take place in some trees both through the phellem and in fissures. The Bark: periderm: phelloderm: Phelloderm is active parenchyma tissue. Parenchyma cells can be used for storage, photosynthesis, defense, and even cell division! The Bark: phloem: Phloem tissue makes up the inner bark. However, it is vascular tissue formed from the vascular cambium. The Bark: phloem: sieve tube elements: Sieve tube elements actively transport photosynthates down the stem. Conifers have sieve cells instead. The cambium: The cambium is the primary meristem producing radial growth. It forms the phloem & xylem. The Xylem (wood): The xylem includes everything inside the vascular cambium. The Xylem: a growth increment (ring): The rings seen in many trees represent one growth increment. Growth rings provide the texture seen in wood. The Xylem: vessel elements: Hardwood species have vessel elements in addition to trachieds. Notice their location in the growth rings of this tree The Xylem: fibers: Fibers are cells with heavily lignified walls making them stiff. Many fibers in sapwood are alive at maturity and can be used for storage. The Xylem: axial parenchyma: Axial parenchyma is living tissue! Remember that parenchyma cells can be used for storage and cell division. -

A Preliminary Checklist of Arizona Macrofungi

A PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF ARIZONA MACROFUNGI Scott T. Bates School of Life Sciences Arizona State University PO Box 874601 Tempe, AZ 85287-4601 ABSTRACT A checklist of 1290 species of nonlichenized ascomycetaceous, basidiomycetaceous, and zygomycetaceous macrofungi is presented for the state of Arizona. The checklist was compiled from records of Arizona fungi in scientific publications or herbarium databases. Additional records were obtained from a physical search of herbarium specimens in the University of Arizona’s Robert L. Gilbertson Mycological Herbarium and of the author’s personal herbarium. This publication represents the first comprehensive checklist of macrofungi for Arizona. In all probability, the checklist is far from complete as new species await discovery and some of the species listed are in need of taxonomic revision. The data presented here serve as a baseline for future studies related to fungal biodiversity in Arizona and can contribute to state or national inventories of biota. INTRODUCTION Arizona is a state noted for the diversity of its biotic communities (Brown 1994). Boreal forests found at high altitudes, the ‘Sky Islands’ prevalent in the southern parts of the state, and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa P.& C. Lawson) forests that are widespread in Arizona, all provide rich habitats that sustain numerous species of macrofungi. Even xeric biomes, such as desertscrub and semidesert- grasslands, support a unique mycota, which include rare species such as Itajahya galericulata A. Møller (Long & Stouffer 1943b, Fig. 2c). Although checklists for some groups of fungi present in the state have been published previously (e.g., Gilbertson & Budington 1970, Gilbertson et al. 1974, Gilbertson & Bigelow 1998, Fogel & States 2002), this checklist represents the first comprehensive listing of all macrofungi in the kingdom Eumycota (Fungi) that are known from Arizona. -

From Dendrochronology to Allometry

Concept Paper From Dendrochronology to Allometry Franco Biondi DendroLab, Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Science, University of Nevada, Reno, NV 89557, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-775-784-6921 Received: 17 December 2019; Accepted: 24 January 2020; Published: 27 January 2020 Abstract: The contribution of tree-ring analysis to other fields of scientific inquiry with overlapping interests, such as forestry and plant population biology, is often hampered by the different parameters and methods that are used for measuring growth. Here I present relatively simple graphical, numerical, and mathematical considerations aimed at bridging these fields, highlighting the value of crossdating. Lack of temporal control prevents accurate identification of factors that drive wood formation, thus crossdating becomes crucial for any type of tree growth study at inter-annual and longer time scales. In particular, exactly dated tree rings, and their measurements, are crucial contributors to the testing and betterment of allometric relationships. Keywords: tree rings; stem growth; crossdating; radial increment 1. Introduction Dendrochronology can be defined as the study and reconstruction of past changes that impacted tree growth. The name of the science derives from the combination of three Greek words: δ"´νδρoν (tree), χρóνo& (time), and λóγo& (study). As past changes can be caused by processes that are internal as well as external to a tree, both environmental factors and tree physiology are subject to dendrochronological inquiry. Knowledge of the principles and methods of tree-ring analysis therefore allows the investigation of topics ranging from climate history to forest dynamics, from the dating of ancient ruins to the timing of wood formation. -

Getting Chemicals Into Trees Without Spraying

Urban Forestry NR/FF/020 (pr) Getting Chemicals Into Trees Without Spraying Michael Kuhns, Forestry Extension Specialist This fact sheet provides an overview of injection, or phellogen that makes cork to thicken the outer bark, implantation, and other ways to get chemicals, mainly phloem that conducts food through the tree from where pesticides, into trees. Many techniques and systems it is stored or made to where it is being used (all of these exist and some are very good, some are good in some tissues together make up the bark), vascular cambium situations, and some are ineffective or bad for trees. that divides rapidly to make new phloem and xylem cells, This fact sheet addresses all of these. and xylem or wood. Xylem includes an outer layer called the sapwood that conducts mostly water and minerals from the roots to the canopy, and an inner layer called the Chemicals are applied to trees for many reasons. heartwood that is aged sapwood that has died and has lost Insecticides repel or kill damaging insects, fungicides its ability to conduct water but still adds strength. treat or prevent fungal diseases, nutrients and plant growth regulators affect growth, and herbicides kill trees or prevent sprouting after tree removal. Spraying is the most typical way to apply these chemicals. It is fast, uses readily available equipment, and is understood. The Phellem (Cork Phellogen down side of spraying is that much of the chemical being or Outer Bark) Phloem applied is wasted, either to drift, run off, or because it can not be applied precisely to where it is needed in the tree. -

Tree Anatomy Stems and Branches

Tree Anatomy Series WSFNR14-13 Nov. 2014 COMPONENTSCOMPONENTS OFOF PERIDERMPERIDERM by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Around tree roots, stems and branches is a complex tissue. This exterior tissue is the environmental face of a tree open to all sorts of site vulgarities. This most exterior of tissue provides trees with a measure of protection from a dry, oxidative, heat and cold extreme, sunlight drenched, injury ridden site. The exterior of a tree is both an ecological super highway and battle ground – comfort and terror. This exterior is unique in its attributes, development, and regeneration. Generically, this tissue surrounding a tree stem, branch and root is loosely called bark. The tissues of a tree, outside or more exterior to the xylem-containing core, are varied and complexly interwoven in a relatively small space. People tend to see and appreciate the volume and physical structure of tree wood and dismiss the remainder of stem, branch and root. In reality, tree life is focused within these more exterior thin tissue sets. Outside of the cambium are tissues which include transport cells, structural support cells, generation cells, and cells positioned to help, protect, and sustain other cells. All of this life is smeared over the circumference of a predominately dead physical structure. Outer Skin Periderm (jargon and antiquated term = bark) is the most external of tree tissues providing protection, water conservation, insulation, and environmental sensing. Periderm is a protective tissue generated over and beyond live conducting and non-conducting cells of the food transport system (phloem). -

Why Do Animals Eat the Bark and Wood of Trees and Shrubs? William R

FNR-203 Purdue University & Natural Re ry sou Forestry and Natural Resources st rc re e o s F Why Do Animals Eat the Bark and Wood of Trees and Shrubs? William R. Chaney, Professor of Tree Physiology Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 PURDUE UNIVERSITY Animals gnawing the bark and wood of trees anatomy, movement and storage of food in trees, and shrubs is not a malicious act or evidence of a and the variations in digestive systems among neurotic condition. Instead, it is the normal means animals. by which some animals acquire a nutritious food source. The ability to consume this seemingly Constituents of Plant Cell Walls unpalatable food supply and derive nourishment Unlike animals, plants have cells with rigid from it requires specialized feeding habits and cell walls composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, digestive systems. and lignins. Pectins help hold the individual cells together in tissues. All of these substances are potential sources of food for animals. Cellulose The most consummate wood feeders are the A principal component of cell walls is billions of termites throughout the world that cellulose, which consists of 5,000 to 10,000 literally devour thousands of tons of woody glucose molecules joined by a so-called beta debris every year in forests as well as lumber linkage to form straight chain polymers of pure in buildings. Many of our most serious and sugar. The long chains of cellulose are combined damaging insect pests are the bark beetles and first into microfibrils and then further into wood borers that feed on the parts of trees for macrofibrils to create a mesh-like matrix of cell which they are named. -

Maine Tree Species Fact Sheet

Maine Tree Species Fact Sheet Common Name: American Chestnut (Chestnut) Botanical Name: Castanea dentata Tree Type: Deciduous Physical Description: Growth Habit: The American chestnut is a rapidly growing tree. The bark on young trees is smooth and reddish-brown in color. On older trees the bark is dark brown, shallowly fissured, with broad, scaly ridges. The twigs are stout, greenish-yellow or reddish-brown in color and somewhat swollen at the base of the buds. The pith is star-shaped in the cross section. The http://www.dcnr.state.pa.us/forestry/commontr/images/AmericanChestnut.gif oblong, simple, alternate leaves are 10 inches long and 2 inches wide. They are narrow at the base, taper-pointed, sharply toothed and smooth on both sides. The leaves are dark green in color above and paler beneath. Height: The chestnut once grew to a height of 60-80 feet tall, sometimes reaching 100 feet or more with a trunk diameter of 10 feet. More commonly, the trunk diameter was 3-4 feet. Shape: In the forest, the chestnut has a tall, straight trunk free of limbs and a small head. When not crowded, the trunk divides into three or four limbs and forms a low, broad top. Fruit/Seed Description/Dispersal Methods: The flowers are monoecious, small and creamy yellow. They appear in catkins up to 8 inches long. They are separate, but usually appear on the same spike in the summer. The fruit is a light brown burr with spines on the outside and hair on the inside. The burr opens with the first frost exposing and dropping three nuts.