Chestnut Culture in California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA Spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION for COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE By Ana Maria Metaxas Approved: James Hill Craddock Jennifer Boyd Professor of Biological Sciences Assistant Professor of Biological and Environmental Sciences (Director of Thesis) (Committee Member) Gregory Reighard Jeffery Elwell Professor of Horticulture Dean, College of Arts and Sciences (Committee Member) A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of the Graduate School CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE by Ana Maria Metaxas A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science May 2013 ii ABSTRACT Chestnut cultivars were evaluated for their commercial applicability under the environmental conditions in Hamilton County, TN at 35°13ꞌ 45ꞌꞌ N 85° 00ꞌ 03.97ꞌꞌ W elevation 230 meters. In 2003 and 2004, 534 trees were planted, representing 64 different cultivars, varieties, and species. Twenty trees from each of 20 different cultivars were planted as five-tree plots in a randomized complete block design in four blocks of 100 trees each, amounting to 400 trees. The remaining 44 chestnut cultivars, varieties, and species served as a germplasm collection. These were planted in guard rows surrounding the four blocks in completely randomized, single-tree plots. In the analysis, we investigated our collection predominantly with the aim to: 1) discover the degree of acclimation of grower- recommended cultivars to southeastern Tennessee climatic conditions and 2) ascertain the cultivars’ ability to survive in the area with Cryphonectria parasitica and other chestnut diseases and pests present. -

Growing Chinese Chestnuts in Missouri by Ken Hunt, Ph.D., Research Scientist, Center for Agroforestry, Blight

AGROFORESTRY IN ACTION University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry AF1007 - 2012 Growing Chinese Chestnuts in Missouri by Ken Hunt, Ph.D., Research Scientist, Center for Agroforestry, blight. In fact, the devastation caused by chestnut blight University of Missouri, Michael Gold, Ph.D., Associate Director, (Cryphonectria parasitica) stem cankers has reduced Center for Agroforestry, University of Missouri, William Reid, American chestnut from a major timber species to a rare Ph.D., Research and Extension Horticulturist, Kansas State Uni- understory tree often found cankered in sprout clumps. versity, & Michele Warmund, Ph.D., Professor of Horticulture, Major efforts are underway to restore the American Division of Plant Sciences, University of Missouri chestnut (see www.acf.org/). The Allegheny and Ozark chinkapins are multi-stem shrubs to small trees that hinese chestnut is an emerging new tree crop produce small tasty nuts and make interesting (but for Missouri and the Midwest. The Chinese blight susceptible) landscape trees that are also useful Cchestnut tree is a spreading, medium-sized tree for wildlife. with glossy dark leaves bearing large crops of nutri- tious nuts. Nuts are borne inside spiny burs that split open when nuts are ripe. Each bur contains one to three shiny, dark-brown nuts. Nuts are "scored" then micro- waved, roasted or boiled to help remove the leathery shell and papery seed coat, revealing a creamy or gold- en-colored meat. Chestnuts are a healthy, low-fat food ingredient that can be incorporated into a wide range of dishes – from soups to poultry stuffing, pancakes, muf- fins and pastries (using chestnut flour). Historically, demand for chestnuts in the United States has been highest in ethnic markets (European and Asian, for example) but as Americans search for novel and healthy food products, chestnuts are becoming more widely accepted. -

Essential Wholesale & Labs Carrier Oils Chart

Essential Wholesale & Labs Carrier Oils Chart This chart is based off of the virgin, unrefined versions of each carrier where applicable, depending on our website catalog. The information provided may vary depending on the carrier's source and processing and is meant for educational purposes only. Viscosity Absorbtion Comparible Subsitutions Carrier Oil/Butter Color (at room Odor Details/Attributes Rate (Based on Viscosity & Absorbotion Rate) temperature) Description: Stable vegetable butter with a neutral odor. High content of monounsaturated oleic acid and relatively high content of natural antioxidants. Offers good oxidative stability, excellent Almond Butter White to pale yellow Soft Solid Fat Neutral Odor Average cold weather stability, contains occlusive properties, and can act as a moistening agent. Aloe Butter, Illipe Butter Fatty Acid Compositon: Palmitic, Stearic, Oleic, and Linoleic Description: Made from Aloe Vera and Coconut Oil. Can be used as an emollient and contains antioxidant properties. It's high fluidiy gives it good spreadability, and it can quickly hydrate while Aloe Butter White Soft Semi-Solid Fat Neutral Odor Average being both cooling and soothing. Fatty Acid Almond Butter, Illipe Butter Compostion: Linoleic, Oleic, Palmitic, Stearic Description: Made from by combinging Aloe Vera Powder with quality soybean oil to create a Apricot Kernel Oil, Broccoli Seed Oil, Camellia Seed Oil, Evening Aloe Vera Oil Clear, off-white to yellow Free Flowing Liquid Oil Mild musky odor Fast soothing and nourishing carrier oil. Fatty Acid Primrose Oil, Grapeseed Oil, Meadowfoam Seed Oil, Safflower Compostion: Linoleic, Oleic, Palmitic, Stearic Oil, Strawberry Seed Oil Description: This oil is similar in weight to human sebum, making it extremely nouirshing to the skin. -

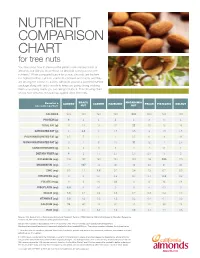

Nutrient Comparison Chart

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

AP-42, CH 9.10.2.2: Peanut Processing

9.10.2.2 Peanut Processing 9.10.2.2.1 General Peanuts (Arachis hypogaea), also known as groundnuts or goobers, are an annual leguminous herb native to South America. The peanut peduncle, or peg (the stalk that holds the flower), elongates after flower fertilization and bends down into the ground, where the peanut seed matures. Peanuts have a growing period of approximately 5 months. Seeding typically occurs mid-April to mid-May, and harvesting during August in the United States. Light, sandy loam soils are preferred for peanut production. Moderate rainfall of between 51 and 102 centimeters (cm) (20 and 40 inches [in.]) annually is also necessary. The leading peanut producing states are Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Florida, and Oklahoma. 9.10.2.2.2 Process Description The initial step in processing is harvesting, which typically begins with the mowing of mature peanut plants. Then the peanut plants are inverted by specialized machines, peanut inverters, that dig, shake, and place the peanut plants, with the peanut pods on top, into windrows for field curing. After open-air drying, mature peanuts are picked up from the windrow with combines that separate the peanut pods from the plant using various thrashing operations. The peanut plants are deposited back onto the fields and the pods are accumulated in hoppers. Some combines dig and separate the vines and stems from the peanut pods in 1 step, and peanuts harvested by this method are cured in storage. Some small producers still use traditional harvesting methods, plowing the plants from the ground and manually stacking them for field curing. -

Is Peanut Butter Keto-Friendly?

Is Peanut Butter Keto-Friendly? Yes! Peanut butter contains carbohydrates, fat, and protein; the ratios of those macronutrients are what makes it acceptable for a keto diet. Our Once Again peanut butters that are made with one simple ingredient: peanuts, are a healthy addition to your keto diet. Peanuts are in the legume family, which includes a variety of beans. Generally speaking, legumes are not included in keto diets; however, peanuts have a higher fat content than other beans which makes them keto-friendly. Moreover, peanuts have a similar macronutrient distribution when compared to nuts such as almonds. They are high in fat and lower in carbs, and thus make a perfect food for the keto lifestyle. Peanut butter fits nicely into your keto diet as a dip for celery, or add it to smoothies, or experiment with it as an ingredient in salad dressings. Is Almond Butter Keto- Friendly? Yes! Almond butter is a staple for most following a keto lifestyle. Used often as a versatile ingredient in salad dressings, dips, and sauces, and in many other culinary innovations, nut butters in general have the desired macronutrient ration for a keto diet, and almond butter is a particularly good choice because of its fiber and vitamin E content. Most of our almond butters contain one simple ingredient: almonds. The newest addition to our product line is our Blanched Almond Butter, available in both in Extra Creamy and Crunchy varieties. Once Again Blanched Almond Butters contain only one gram of carbohydrate per serving! Blanching almonds involves removing the exterior of the almond, leaving behind a surprisingly nutty-sweet interior, with its lighter texture and color. -

Frank Meyer, Isabel Shipley Cunningham Agricultural Explorer

Frank Meyer, Isabel Shipley Cunningham Agricultural Explorer For 60 years the work of Frank N. Meyer has 2,500 pages of his letters tell of his journeys remained a neglected segment of America’s and the plants he collected, and the USDA heritage. Now, as people are becoming con- Inventory of Seeds and Plants Imported con- cerned about feeding the world’s growing tains descriptions of his introductions. population and about the loss of genetic di- Until recently little was known about the versity of crops, Meyer’s accomplishments first 25 years of Meyer’s life, when he lived have a special relevance. Entering China in in Amsterdam and was called Frans Meijer. 1905, near the dawn of the single era when Dutch sources reveal that he was bom into a explorers could travel freely there, he be- loving family in 1875. Frans was a quiet boy, came the first plant hunter to represent a who enjoyed taking long walks, reading government and to search primarily for eco- about distant lands, and working in his fami- nomically useful plants rather than orna- ly’s small garden. By the time he had mentals. No one before him had spent 10 fimshed elementary school, he knew that ’ years crossing the mountains, deserts, farms, wanted to be a world traveler who studied he ’,if and forests of Asia in search of fruits, nuts, plants; however, his parents could not afford vegetables, grains, and fodder crops; no one to give him further education. When he was has done so since. 14 years old, he found work as a gardener’s During four plant-hunting expeditions to helper at the Amsterdam Botanical Garden. -

Chestnut Growers' Guide to Site Selection and Environmental Stress

This idyllic orchard has benefited from good soil and irrigation. Photo by Tom Saielli Chestnut Growers’ Guide to Site Selection and Environmental Stress By Elsa Youngsteadt American chestnuts are tough, efficient trees that can reward their growers with several feet of growth per year. They’ll survive and even thrive under a range of conditions, but there are a few deal breakers that guarantee sickly, slow-growing trees. This guide, intended for backyard and small-orchard growers, will help you avoid these fatal mistakes and choose planting sites that will support strong, healthy trees. You’ll know you’ve done well when your chestnuts are still thriving a few years after planting. By then, they’ll be strong enough to withstand many stresses, from drought to a caterpillar outbreak, with much less human help. Soil Soil type is the absolute, number-one consideration when deciding where—or whether—to plant American chestnuts. These trees demand well-drained, acidic soil with a sandy to loamy texture. Permanently wet, basic, or clay soils are out of the question. So spend some time getting to know your dirt before launching a chestnut project. Dig it up, roll it between your fingers, and send in a sample for a soil test. Free tests are available through most state extension programs, and anyone can send a sample to the Penn State Agricultural Analytical Services Lab (which TACF uses) for a small fee. More information can be found at http://agsci.psu.edu/aasl/soil-testing. There are several key factors to look for. The two-foot-long taproot on this four- Acidity year-old root system could not have The ideal pH for American chestnut is 5.5, with an acceptable range developed in shallow soils, suggesting from about 4.5 to 6.5. -

5 Fagaceae Trees

CHAPTER 5 5 Fagaceae Trees Antoine Kremerl, Manuela Casasoli2,Teresa ~arreneche~,Catherine Bod6n2s1, Paul Sisco4,Thomas ~ubisiak~,Marta Scalfi6, Stefano Leonardi6,Erica ~akker~,Joukje ~uiteveld', Jeanne ~omero-Seversong, Kathiravetpillai Arumuganathanlo, Jeremy ~eror~',Caroline scotti-~aintagne", Guy Roussell, Maria Evangelista Bertocchil, Christian kxerl2,Ilga porth13, Fred ~ebard'~,Catherine clark15, John carlson16, Christophe Plomionl, Hans-Peter Koelewijn8, and Fiorella villani17 UMR Biodiversiti Genes & Communautis, INRA, 69 Route d'Arcachon, 33612 Cestas, France, e-mail: [email protected] Dipartimento di Biologia Vegetale, Universita "La Sapienza", Piazza A. Moro 5,00185 Rome, Italy Unite de Recherche sur les Especes Fruitikres et la Vigne, INRA, 71 Avenue Edouard Bourlaux, 33883 Villenave d'Ornon, France The American Chestnut Foundation, One Oak Plaza, Suite 308 Asheville, NC 28801, USA Southern Institute of Forest Genetics, USDA-Forest Service, 23332 Highway 67, Saucier, MS 39574-9344, USA Dipartimento di Scienze Ambientali, Universitk di Parma, Parco Area delle Scienze 1lIA, 43100 Parma, Italy Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, 5801 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA Alterra Wageningen UR, Centre for Ecosystem Studies, P.O. Box 47,6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA lo Flow Cytometry and Imaging Core Laboratory, Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason, 1201 Ninth Avenue, Seattle, WA 98101, -

Sample Planting Grids All Chestnuts in the Planting Must Have Permanent Embossed Numerical Tags for That Planting and Will Be Monitored by That Tag

Sample planting grids All chestnuts in the planting must have permanent embossed numerical tags for that planting and will be monitored by that tag. The basic module is 6 x 6 ft spacing with a minimum of 20 ft borders. Such plantings allow easy fencing and mowing. Rows and columns need not be continuous nor do they need to be the same length. Mapping should show gaps. Create a simple schematic map of the planting once done. These configurations can be modified in a wide variety of ways but if lengthened in either direction, a depth of a least 3 rows in any dimension should be maintained. Remember that the pines are an early succession planting designed to create early site coverage and encourage upward growth in hardwoods. Their removal will be a first step in thinning. Different configurations will impose other thinning regimens over time: for example, red oaks might be removed in #1 over time if there is high chestnut survival and vigorous growth. These plantings are designed to introduce at least 30 chestnuts on the site. These should represent at least 2‐3 chestnut families, and may include Kentucky stump sprout families. #1. Alternate row planting 024 ft 30 ft 36 ft 42 ft 48 ft 54 ft 60 ft 66 ft 72 ft 78 ft 98 ft Dimensions 24 ft Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Red Oak 110 x 98 ft 10780 sq ft 30 ft Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Chestnut 36 ft Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Red Oak Acreage 42 ft Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut -

Canarium Ovatum) Shells

International Journal of Engineering Research And Management (IJERM) ISSN: 2349- 2058, Volume-04, Issue-09, September 2017 Physical and Mechanical Properties of Particleboard Utilizing Pili Nut (Canarium Ovatum) Shells Ariel B. Morales are widely used for various purposes. It is a lightweight and Abstract— This study aims to make a 200 mm x 200 mm strong kind of plastic that can be easily remolded into particleboard with nine millimeter thickness using Crushed Pili different shapes [5]. This study also helps in lessening Nut Shells (CPNS) and sawdust as raw materials with the ratios non-biodegradable wastes and be useful as a resin. This study (CPNS: sawdust) 100:0, 75:25, and 50:50 by weight and determine their physical and mechanical properties. Also, the specifically aims the following objectives: results were compared to the standard properties of commercial • To determine its physical property such as density, unit particleboard set classified by the Philippine Standard weight and thickness swelling, Association (PHILSA). The raw materials were mixed with • To determine the mechanical property, specifically High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) as an adhesive. All Modulus of Rupture (MOR). particleboards have passed and exceeded the PHILSA standard • To compare the results to the standard properties for for particle board where 100:0 mixtures with density of 1204.09 kg/m3 has the highest MOR of 110 MPa and lowest thickness commercial particleboard from Philippine Standard swelling of 1.11%. Therefore, particleboard made from Pili nut Association (PHILSA) if it will pass or exceed the given shells has an outstanding property compared to commercial standards. particleboards that depends on its application. -

Castanea Sativa Mill

Forest Ecology and Forest Management Group Tree factsheet images at pages 3, 4, 5, 6 Castanea sativa Mill. taxonomy author, year Miller, … synonym C. vesca Gaertn. Family Fagaceae Eng. Name Sweet Chestnut tree, Spanish Chestnut, European Chestnut Dutch name Tamme kastanje subspecies - varieties - hybrids - cultivars, frequently used references Weeda 2003, Nederlandse oecologische flora, vol.1 (Dutch) PFAF database http://www.pfaf.org/index.html morphology crown habit tree, round max. height (m) 30 max. dbh (cm) 300 actual size Europe 2000? years old, d(..) 197, Etna, Sicily , Italy actual size The Netherlands year 1600-1700, d (130) 270, h 25, Kabouterboom, Beek-Ubbergen year 1810-1820, d(130) 149, h 30 leaf length (cm) 10-27 leaf petiole (cm) 2-3 leaf colour upper surface green leaf colour under surface green leaves arrangement alternate flowering June flowering plant monoecious flower monosexual flower diameter (cm) 1 flower male catkins length (cm) 8-12 pollination wind fruit; length burr (Dutch: bolster) containing 2-3 nuts; 6-8 cm fruit petiole (cm) 1 seed; length nut; 5-6 cm seed-wing length (cm) - weight 1000 seeds (g) 300-1000 seeds ripen September seed dispersal rodents: Apodemus -species – Wood mice - bosmuizen rodents: Sciurus vulgaris - Squirrel - Eekhoorn birds: Garulus glandarius – Jay –Gaai habitat natural distribution Europe, West Asia in N.W. Europe since 9000 B.C. natural areas The Netherlands forests geological landscape types The Netherlands loss-covered terraces, ice pushed ridges (Hoek 1997) forested areas The Netherlands loamy and sandy soils. area Netherlands < 1700 (2002, Probos) % of forest trees in the Netherlands < 0,7 (2002, Probos) soil type pH-KCl indifferent soil fertility nutrient medium to rich light highly shade tolerant as a sapling, shade tolerant when mature shade tolerance 3.2 (0=no tolerance to 5=max.