Chestnut Growers' Guide to Site Selection and Environmental Stress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample Planting Grids All Chestnuts in the Planting Must Have Permanent Embossed Numerical Tags for That Planting and Will Be Monitored by That Tag

Sample planting grids All chestnuts in the planting must have permanent embossed numerical tags for that planting and will be monitored by that tag. The basic module is 6 x 6 ft spacing with a minimum of 20 ft borders. Such plantings allow easy fencing and mowing. Rows and columns need not be continuous nor do they need to be the same length. Mapping should show gaps. Create a simple schematic map of the planting once done. These configurations can be modified in a wide variety of ways but if lengthened in either direction, a depth of a least 3 rows in any dimension should be maintained. Remember that the pines are an early succession planting designed to create early site coverage and encourage upward growth in hardwoods. Their removal will be a first step in thinning. Different configurations will impose other thinning regimens over time: for example, red oaks might be removed in #1 over time if there is high chestnut survival and vigorous growth. These plantings are designed to introduce at least 30 chestnuts on the site. These should represent at least 2‐3 chestnut families, and may include Kentucky stump sprout families. #1. Alternate row planting 024 ft 30 ft 36 ft 42 ft 48 ft 54 ft 60 ft 66 ft 72 ft 78 ft 98 ft Dimensions 24 ft Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Red Oak 110 x 98 ft 10780 sq ft 30 ft Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Chestnut 36 ft Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Red Oak Acreage 42 ft Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut -

Chestnut Oak Botanical/Latin Name Quercus Montana

Chestnut Oak Botanical/Latin name Quercus Montana Chestnut Oak owes its name to its leaves, 4”-6” long, looking like those of the American Chestnut. It is a species of oak in the white oak group native to eastern U.S. Predominantly a ridge-top tree in hardwood forests. Also called Mountain Oak or Rock Oak because it grows in dry rocky habitats, sometimes even around large rocks. As a consequence of its dry habitat and harsh ridge-top exposure, it is not usually large, 59’–72’ tall; specimens growing in better conditions however can become large, up to 141’. It is a long-lived tree, with high-quality timber when well-formed. The heavy, durable, close-grained wood is used for fence posts, fuel, railroad ties and tannin. Saplings are easier to transplant than many other oaks because the taproot of the seedling disintegrates as the tree grows, and the remaining roots form a dense mat about three feet deep. It is monoecious, having pollen-bearing catkins in mid-spring that fertilize the inconspicuous female flowers on the same tree. It reproduces from seed as well as stump sprouts. The 1”-1-1/2” long acorns mature in one growing season, are among the largest of native American oaks and are a valuable wildlife food. Acorns are produced when a tree grown from seed is about 20 years of age, but sprouts from cut stumps can produce acorns in as little as three years after cutting. Extensive confusion between the chestnut oak (Q. montana) and the swamp chestnut oak (Quercus michauxii) has historically occurred. -

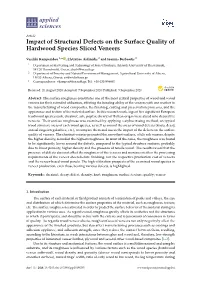

Impact of Structural Defects on the Surface Quality of Hardwood Species Sliced Veneers

applied sciences Article Impact of Structural Defects on the Surface Quality of Hardwood Species Sliced Veneers Vasiliki Kamperidou 1,* , Efstratios Aidinidis 2 and Ioannis Barboutis 1 1 Department of Harvesting and Technology of Forest Products, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 541 24 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] 2 Department of Forestry and Natural Environment Management, Agricultural University of Athens, 118 55 Athens, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2310998895 Received: 20 August 2020; Accepted: 7 September 2020; Published: 9 September 2020 Abstract: The surface roughness constitutes one of the most critical properties of wood and wood veneers for their extended utilization, affecting the bonding ability of the veneers with one another in the manufacturing of wood composites, the finishing, coating and preservation processes, and the appearance and texture of the material surface. In this research work, logs of five significant European hardwood species (oak, chestnut, ash, poplar, cherry) of Balkan origin were sliced into decorative veneers. Their surface roughness was examined by applying a stylus tracing method, on typical wood structure areas of each wood species, as well as around the areas of wood defects (knots, decay, annual rings irregularities, etc.), to compare them and assess the impact of the defects on the surface quality of veneers. The chestnut veneers presented the smoothest surfaces, while ash veneers, despite the higher density, recorded the highest roughness. In most of the cases, the roughness was found to be significantly lower around the defects, compared to the typical structure surfaces, probably due to lower porosity, higher density and the presence of tensile wood. -

American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast

American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast Ohio A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Nathan A. Daniel June 2012 © 2012 Nathan A. Daniel. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast Ohio by NATHAN A. DANIEL has been approved for the Program of Environmental Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences by James M. Dyer Professor of Geography Brian C. McCarthy Professor of Environmental and Plant Biology Howard Dewald Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT DANIEL NATHAN A., M.S., June 2012, Environmental Studies American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast Ohio (51 pp.) Directors of Thesis: James M. Dyer and Brian C. McCarthy Restoration of American chestnut (Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh.) is currently underway in eastern North American forests. American chestnut and eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carr.) trees historically co-occurred in these forests. Today, hemlock-dominated forests are in decline due to hemlock wooly adelgid (Adelges tsugae Annand) infestation, and as such, may serve as appropriate habitat for chestnut reestablishment. To investigate this notion, I evaluated the performance of American chestnut seedlings planted under healthy eastern hemlock-dominated canopies. Two process-oriented greenhouse experiments were also performed to study the response of American chestnut to drought stress and to test the competitive performance of chestnut against red maple (Acer rubrum (L.)), the most abundant hardwood found in the understory of regional hemlock-dominated forests. -

Chestnut Oak Forest/Woodland

Classification of the Natural Communities of Massachusetts Terrestrial Communities Descriptions Chestnut Oak Forest/Woodland Community Code: CT1A3A0000 State Rank: S4 Concept: Oak forest of dry ridgetops and upper slopes, dominated by chestnut oak with an often dense understory of scrub oak, heaths, or mountain laurel. Environmental Setting: Chestnut Oak Forests/Woodlands occur as long narrow bands along dry ridges and upper slopes with thin soil over acidic bedrock. They may extend down steep, convex, rocky, often west- or south-facing slopes where soil is shallow and dry. The canopy is closed to partially open (>25% cover). There tends to be deep oak leaf litter with slow decomposition. Often many trees have multiple fire scars and charred bases; fire appears to play a role in maintaining the community occurrences. Chestnut Oak Forests/Woodlands often occur in a mosaic with closed oak or pine - oak forests down slope and more open communities above. Vegetation Description: The canopy of Chestnut Oak Forests/Woodlands is dominated, often completely, by chestnut oak (Quercus montana). Less abundant associates include other oaks (black (Q. velutina), red (Q. rubra), and/or white (Q. alba), and less commonly, scarlet (Q. coccinea)), with red maple (Acer rubrum), and white or pitch pines (Pinus strobus, P. rigida). The subcanopy layer is sparse and consists of canopy species, black birch (Betula lenta), and sassafras (Sassafras albidum). Tall shrubs are lacking or the shrub layer may have scattered tree saplings, mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum), American chestnut (Castanea dentata), and witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana). Short shrubs are dense in patches dominated by black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata) and lowbush blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium and V. -

Victoria-Park-Tree-Walk-2-Web.Pdf

Opening times Victoria Park was London’s first The park is open every day except Christmas K public ‘park for the people’. K Day 7.00 am to dusk. Please be aware that R L Designed in 1841 by James A closing times fluctuate with the seasons. The P A specific closing time for the day of your visit is Pennethorne, it covers 88 hectares A I W listed on the park notice boards located at and contains over 4,500 trees. R E O each entrance. Trees are the largest living things on E T C Toilets are opened daily, from 10.00 am until R the planet and Victoria Park has a I V T one hour before the park is closed. variety of interesting specimens, Getting to the park many of which are as old as the park itself. Whatever the season, as you Bus: 277 Grove Road, D6 Grove Road, stroll around take time to enjoy 8 Old Ford Road their splendour, whether it’s the Tube: Mile End, Bow Road, Bethnal Green regimental design of the formal DLR: Bow Church tree-lined avenues, the exotic trees Rail: Hackney Wick (BR North London Line) from around the world or, indeed West Walk the evidence of the destruction caused by the great storm of 1987 that reminds us of the awesome power of nature. The West Walk is one of three Victoria Park tree walks devised by Tower Hamlets Council. We hope you enjoy your visit, if you have any comments or questions about trees please contact the Arboricultural department on 020 7364 7104. -

Chestnut Oak Shortleaf Pine

Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) Chestnut Oak (Quercus prinus) The Need to Know: How Trees Grow Paul Wray Paul Wray Paul Paul Wray Paul Kentucky Forestry Kentucky Forestry The Eastern Red Cedar is actually in the juniper family and is not closely related Although its serrated leaves resemble those of an American chestnut, this tree to other cedars. Its tough, stringy bark and waxy, scaly needles are designed for is actually a species of oak. It is also referred to as rock oak because it likes to survival in very dry conditions. The berries of the red cedar are an important food grow in rocky areas. The bark of a chestnut oak has vertical rectangular chunks. source for many songbirds. The wood is prized by builders for its rich red color, Good acorn crops are infrequent, but when available, the sweet nuts are eaten by sweet smell, and weather-resistant properties. deer, wild turkeys, squirrels and chipmunks. Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia) White Oak (Quercus alba) Paul Wray Paul Paul Wray Paul Richard Webb Richard This evergreen shrub can be found in a variety of habitats along Eastern North The leaves of the white oak have rounded lobes, and the bark is light gray and America. It has a gnarled, multi-stemmed trunk with ridged bark, and typically scaly on older trees. The acorns are elongated with a shallow cap, and have a grows as a rounded, dense shrub of 5-15 feet tall. The leaves are broad with sweet taste, which makes them a favorite food for deer, bear, turkeys, squirrels pointed tips, and the mountain laurel’s noteworthy cup-shaped flowers bloom in and other wildlife. -

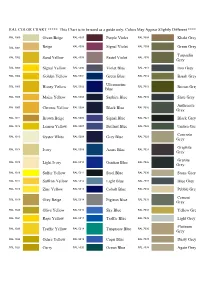

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

Restoration of the American Chestnut in New Jersey

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Restoration of the American Chestnut in New Jersey The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is a tree native to New Jersey that once grew from Maine to Mississippi and as far west as Indiana and Tennessee. This tree with wide-spreading branches and a deep broad-rounded crown can live 500-800 years and reach a height of 100 feet and a diameter of more than 10 feet. Once estimated at 4 billion trees, the American chestnut Harvested chestnuts, early 1900's. has almost been extirpated in the last 100 years. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, New Jersey Field Value Office (Service) and its partners, including American Chestnut The American chestnut is valued Cooperators’ Foundation, American for its fruit and lumber. Chestnuts Chestnut Foundation, Monmouth are referred to as the “bread County Parks, Bayside State tree” because their nuts are Prison, Natural Lands Trust, and so high in starch that they can several volunteers, are working to American chestnut leaf (4"-8"). be milled into flour. Chestnuts recover the American chestnut in can be roasted, boiled, dried, or New Jersey. History candied. The nuts that fell to the ground were an important cash Chestnuts have a long history of crop for families in the northeast cultivation and use. The European U.S. and southern Appalachians chestnut (Castanea sativa) formed up until the twentieth century. the basis of a vital economy in Chestnuts were taken into towns the Mediterranean Basin during by wagonload and then shipped Roman times. More recently, by train to major markets in New areas in Southern Europe (such as York, Boston, and Philadelphia. -

Download Colour Chart

DIRECT DYE * AMMONIA FREE * PEROXIDE FREE DIRECTIONS: CUSTOMISED COLOUR MAINTENANCE APPLICATION MIXING TIMING refer to menu for depending on hair condition suggested formulas and desired colour intensity colour maintenance add 80g fab pro 3 minutes conditioner formula (direct dye match and maintain colour or direct dye and in-between salon visits. conditioner) to 200ml conditioner base. shake well. MATCH IT * MIX IT * TAKE IT AWAY DIRECTIONS: COLOUR SERVICE 1. identify the level, tone and length of hair. 2. select the appropriate colour formula from the mixologist menu, ensuring the formula works with the lightest level of hair. 3. measure and mix your formula. 4. prepare hair by shampooing, towel-dry hair evenly, then detangle and comb through. APPLICATION MIXING TIMING refer to menu for depending on hair condition suggested formulas and desired colour intensity colour refresh mix fab pro direct 5 – 15 minutes refresh existing hair colour dyes together. on mid-lengths and ends in-between all colour services (permanent, demi and semi- permanent colour). colour fill* mix fab pro direct 5 – 15 minutes darken lighter hair quickly, dyes together. without damage. *for filling formulas, see fab pro fill chart or visit evohair.com. colour tone* / pastels mix fab pro direct 5 – 15 minutes ideal for colour toning and dyes together or with can be diluted to create pastel shades. conditioner base. *for extremely porous hair, you may need to dilute fab pro direct dye using conditioner base. DIRECT DYES LEVEL 5 LEVEL 7 LEVEL 10 colour results are determined by the level, tone and formula you use. in order to accurately predict a colour result, you need to understand how the existing level and tone will contribute to the result; the lighter the level, the more intense the result. -

Chestnuts in Appalachian Culture Part II Chestnuts in Appalachian Culture Part II a Perfect Wildlife Food Lost in Time, But

the September 2010 | Issue 2 Vol.24 27th Annual Meeting October 15-17 Registration Information Inside Chestnuts in Appalachian Culture Part II A Perfect Wildlife Food Lost in Time, But Not Forgotten Simple Strategies for Controlling a Common Pest MeadowviewMeadowview DedicationDedication a Success!S ! 27th REGISTER ONLINE AT WWW.ACF.ORG REGISTRATIONANNUAL MEETING OR CALL (828) 281-0047 TO REGISTER BY PHONE THE AMERICAN CHESTNUT FOUNDATION Option 1: Full Registration PAYMENT TACF Member $75 Name of Attendee(s) Non-Member $115 (includes a one-year membership) Address Full Registration for one person City (does not include lodging) State Includes: Zip Code Phone number t Friday Night Welcome Reception t Saturday Night Dinner & Awards Program Email t Access to all Workshops Form of Payment t All Meals Check (payable to TACF) Credit Card Option 2: Day Passes for Workshops Only (Registration fee does not include lodging Total amount due $ or meals) Credit Card Billing Information SATURDAY Credit Card (circle one): Visa Mastercard Regular Members $40 Card Number __ __ __ __-__ __ __ __-__ __ __ __-__ __ __ __ Student Members $40 Regular Non-Member $80 (includes a one-year membership) Expiration Date Student Non-Member $55 (includes a one-year membership) Name on Card (print) SUNDAY Address Regular Members $25 City Student Members $25 State Zip Code Regular Non-Member $65 (includes a one-year membership) Student Non-Member $40 (includes a one-year membership) Phone number All attendees MUST pre-register for the Annual Meeting. Signature TACF needs to register all of our attendees with NCTC’s security office prior to the meeting, and no on-site Return form and payment to: registration will be available. -

American Chestnut Castanea Dentata

Best Management Practices for Pollination in Ontario Crops www.pollinator.ca/canpolin American Chestnut Castanea dentata Tree nuts are usually grown under warmer conditions than are found in Ontario, but there are several types of nuts native to the province that are of interest for local consumption or commercial development (beaked hazelnut, black walnut). There are some non-native commercial species that have been imported. Many nuts require long hot growing seasons, and be- cause they are growing near the northern limit of hardiness, they can be a risky crop. Most are wind-pollinated and self- fruitful, although there are exceptions, and wild populations of at least some species appear to have mechanisms in place to encourage cross-fertilization, and produce higher quality nuts when cross-pollinated. Pollination Recommendations The chestnut was once an important tree in eastern deciduous forests, with the northern edge of its distribution in southern Ontario. After the chestnut blight was introduced in 1904, the species declined precipitously in the wild, and few trees re- main in Ontario forests. Chestnut is self-compatible, but still requires cross-pollination because the male and female flowers do not bloom at the same time on an individual tree. The flowers are in the form of catkins, and a variety of pollinators collect both nectar and pollen from the flowers. Unlike most other nut trees, the American chestnut is pollinated by insects. Wild trees generally cannot reproduce due to the isolation of individual trees, and artificial propagation is necessary to propagate the species. In the related Caucasian chestnut tree, Castanea sativa, pollination by honey bees can improve total nut yield.